Chapter 37

Blue Machine Axis

The blue machine innovations made by Atkins, Wickson, and Lind, on full display in Ontario’s 1971 election, showed what the Tories could bring to their 1972 re-match against Pierre Trudeau.

Ontario would be a major battleground for the election, so Atkins wanted to further strengthen the axis between blue machinists in Toronto and Ottawa through closer integration with the national party.

When Dalton was president, the blue machine’s hold on the national party was direct. Since then, restless Frank Moores, Dalton’s blue machine–friendly successor, had departed Ottawa to lead the Newfoundland PCs. It was time to prepare for the party’s 1971 annual meeting, which would elect a new slate of officers. However, the contest was becoming quite bizarre, primarily because of those now counselling Stanfield.

The presidency was shaping up as a battle between two strong Tories, neither of them blue machinists. Donald Matthews of London, a wealthy contractor and member of John Robarts’s circle, was in the race, as was Alberta’s influential Roy Deyell. The people around Stanfield wanted to see the Albertan elected, to help secure that province’s political base. In line with this thinking, they had Stanfield ask Atkins to run somebody from Ontario, because under the constitution the party’s president and vice-president could not both come from the same province.

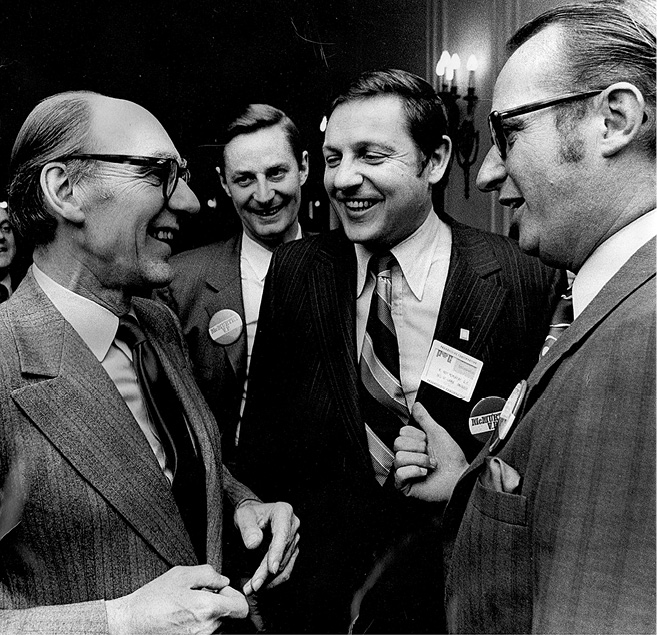

Stanfield interacts with Spades Don Guthrie and Roy McMurtry, and Newfoundland MP Frank Moores, who’d replaced Camp as PC party president. At this annual meeting in Ottawa, McMurtry was a candidate for national vice-president, as the party and the blue machine sought to juggle the talent lineup.

So the blue machine, following the leader’s wishes, mounted a campaign for Roy McMurtry as party vice-president. The Atkins team, with no particular grievance against Don Matthews, set about to defeat him by supporting Roy Deyell. Atkins encouraged the newly elected PC Youth Federation’s policy vice-president, Hugh Segal, to recruit youth voters for McMurtry. He did so keenly. “Having McMurtry, close friend of Davis, Camp, and Atkins, as second top person in the national party,” enthused Hugh, “would blend the Ontario blue machine with the federal organization in a way that would achieve the required co-operation between Ontario and the feds if we were to win the coming 1972 election.” Meanwhile, with mixed signals from the leader’s office, Stanfield’s own riding president nominated Don Matthews!

In the end, Matthews was elected PC national president and Deyell went on the executive as vice-president. McMurtry returned to his Toronto law practice and Ontario political focus.

———

A much simpler way to strengthen the Tory campaigners’ axis between Ottawa and Toronto had, to Norman’s relief, already been established when he and Wickson shared preparations for the 1971 Ontario election. After the Davis victory, partisan planning at the Camp agency continued uninterupted, with the two of them relying on the same talented team, the only difference being that for their next campaign, they’d all be working to elect Stanfield.

In November 1971, Norman invited the Dirty Dozen to dine at the Albany Club. He congratulated the advance men. “You did a great job for Mr. Davis,” he said, “and now we would like you to meet Bob Stanfield and do for him what you did for the premier.” Ontario’s premier, also attending, urged the Dirty Dozen volunteers “to carry on and do what you have done provincially, federally.”

Among the advance team recruits that night was Paul Curley. With a keen interest in politics dating back to his days at the University of Ottawa, Paul had been enlisted, along with Tom MacMillan, by his university buddy John Thompson to work in Darcy McKeough’s campaign to become Ontario PC leader and premier.

Not long after the convention, Curley got a call from Hugh Macaulay, who asked him if he wanted to be an advance man for the Davis campaign in the coming election. Curley didn’t know what he was being asked, but understood there was only one correct answer to the question.

Now a volunteer for the Davis campaign, Curley had only to cross the street: the PC headquarters on Adelaide Street faced the front door of Rio Algom, where he worked. From Norman Atkins he received a Guide to Advance the Hon. Robert L. Stanfield, Federal Election, 1972, a confidential sixteen-page manual, numbered and assigned to him by name. It was a condensed version of the handbook issued the year before to those advancing the leader’s tour for Bill Davis, the Canadianized version of Jerry Bruno’s manual for pulling off battlefield triumphs.

Several weeks later, Atkins and Curley were in British Columbia for the November 28 Grey Cup game at Empire Stadium. Davis, who’d been a varsity football player at the University of Toronto with McMurtry, was on hand too, cheering for the Toronto Argonauts, happy the team’s colour was blue. Also in the stands was Peter Lougheed, who four months earlier, fully independent of the Camp-Atkins organization, had ousted Alberta’s Social Credit dynasty in a stunning electoral upset to become the province’s first Progressive Conservative premier. Lougheed, who’d played two seasons of pro football with the Edmonton Eskimos, displayed his enthusiasm for Toronto’s rivals, the Calgary Stampeders.

In addition to a love of football, the two fresh Progressive Conservative premiers of powerhouse provinces came from very political families and were lawyers. Even the teams they supported were closely matched. The Argos and Stamps battled through a very tight game on the rain-slicked gridiron until Calgary finally claimed the celebrated Cup, 14–11.

After the game, Atkins spotted Curley and introduced him to Vancouverite Malcolm Wickson. The three went into a coffee shop to continue their discussion. Malcolm asked Paul more about his background, and learned he was bilingual, from Ottawa, had worked in Montreal, had a university degree and had also studied abroad, had worked in the private sector, and was now in Toronto. It was as if a halo appeared over Curley’s head. For several weeks Norman canvassed other potential prospects for the job of Malcolm’s executive assistant, and made endless soundings about Curley. In the end, the decision made, he telephoned Curley.

Curley quit his job at Rio, moved back to Ottawa, and reported for duty as executive assistant to the national director of a major Canadian political party, “not knowing what my job was or even why they wanted me to do it. But I was single, bilingual, and took the job.”

———

Wickson in Ottawa was campaign chairman, Atkins in Toronto was communications coordinator for the national campaign, and Curley now was their resourceful and intelligent go-between.

Malcolm knew quite a few Tory operatives, having been national director since 1968, but to fill the campaign’s organization chart, he and Norman increasingly tapped the blue machine’s own roster of top organizers across Canada. “I kept in touch with everyone in the field and throughout the organization,” said Curley, “to make sure each person knew what they were supposed to be doing.” Keeping tabs on them all, he grew familiar with the blue machine’s most trusted contacts, a national network of exceptional campaign organizers.

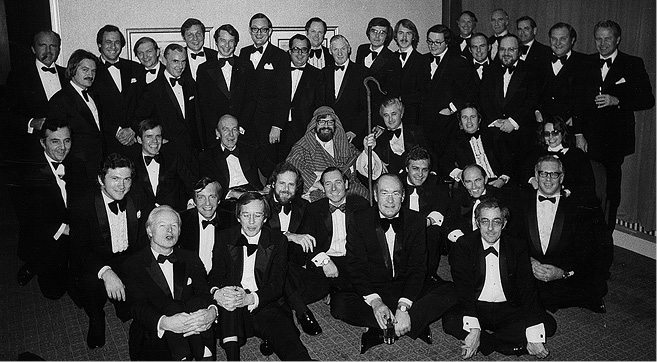

Malcolm Wickson, the “Good Shepherd” of the Progressive Conservatives, sits amidst his flock of “black sheep,” including, at his right Robert Stanfield, Murray Coolican, and Gerry Nori, Ontario PC president; and at his left, Nate Nurgitz of Winnipeg. In the back, behind Stanfield, are Roy McMurtry and Brian Armstrong, then Tom MacMillan and Hugh Segal. The three standing at the very right are Paul Weed, Norman Atkins, and Hugh Macaulay. National tour director John Thompson sits in front of Nurgitz, and at the end of that row to right is Spade Eric Ford in dark-rimmed glasses. Seated in front of Stanfield are Michael Gee, director of Ontario PC Caucus Services, and Paul Curley. All present were key to the Tory organization.

“A lot of major federal PC campaign decisions were being made in the Camp offices,” Curley observed, “long before a separate election headquarters in downtown Toronto was set up.” At the Camp agency, election preparation teams were established with PC organizers for every province. Detailed arrangements were worked out with the secret specialist advertising consortium, code named PACE. Public opinion polling work was projected, with Bob Teeter and Fred Steeper coming to the agency from Detroit for meetings, figuring out better ways to project Stanfield’s image that would align perceptions of him with public concerns about the economy. The 1972 tour planning team was assembled, including a specialized unit to organize everything with airplanes.

The Progressive Conservative’s national campaign would be headquartered in Toronto. Curley, now an integral part of the Ottawa-Toronto axis, became “the guy who kept in touch with everybody in the campaign organization as Malcolm and Norman built the campaign itself.”

One year after their Ontario election victory, the original 1971 Dirty Dozen advance team celebrated, inviting Norman Atkins and Malcolm Wickson to join them at Toronto’s King Edward Hotel. Conditioned to create photo ops, advance men Peter Groschel and Tom MacMillan placed their lone table dead centre in the ballroom and had this memorable image shot from above.

———

Ontario was the primary battleground because the province’s electorate was more volatile than voters in Canada’s other regions and because a great many seats were in play.

In the four Atlantic provinces to the east and the four provinces to the west, Tories worked hard, held firm, and feared fickle Ontarians might deny them a national victory. What happened in Quebec, where Norman interacted principally with Richard LeLay, Stanfield’s French-language press secretary, and Quebec PC organizer Jean Peloquin, would be a case unto itself.

Norman Atkins and Malcolm Wickson, dining at the Albany Club, spent a great deal of time together building a strong Ottawa-Ontario blue machine axis for Progressive Conservative election campaigns.

Crucial to the Ontario theatre of battle was that Bill Davis wanted to play a major role in the national campaign. He led his entire provincial PC organization into action for Stanfield. Davis himself spent all available time working for the cause, appearing at meetings with the leader, speaking in individual ridings on behalf of PC candidates, peppering the province with timely phone calls. At Queen’s Park, Brian Armstrong aligned his calendar to the campaign’s needs. When not in Davis’s office, he went downtown to work in the campaign office on Adelaide Street, to ensure maximum coordination.

The set-up was familiar, to Armstrong and most others, because the same building had been used as provincial campaign headquarters the year before. Some elements of the national campaign were being handled in Ottawa, but this was the main engine room for the Canada-wide effort.

Here Atkins and Wickson continued working closely throughout the election, taking special pride in collaborating with PACE to produce television commercials that campaign veterans considered “brilliant.” Curley worked out of Ottawa at PC Party headquarters, travelled a lot, was on the campaign plane with the leader, and “followed up on a lot of stuff Malcolm did not have time to do. Like a ‘gofer’ I did whatever needed doing.”

———

The word went out “all hands on deck” once the election was called for October 30.

Camp telephoned the Spades, and a few others, to tell them he would not contest the election. He explained to Bill Davis that he wanted to continue his new work, outside partisan politics, as a member of the Ontario Royal Commission on Book Publishing, to which John Robarts had appointed him in December 1970.

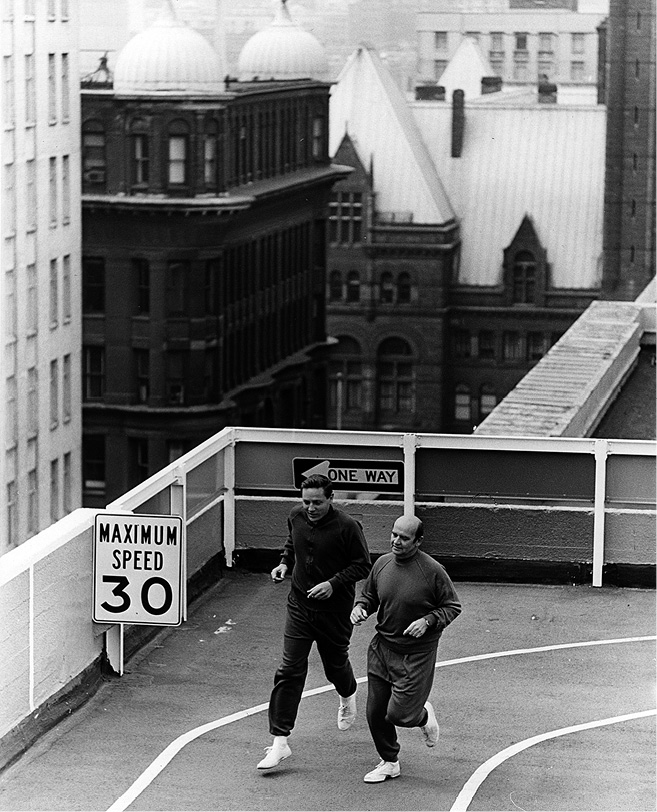

Roy McMurtry paces Dalton Camp as they count out laps in downtown Toronto, the two hatching political strategy in locker rooms as well as party backrooms. At this time, as Dalton was beginning to withdraw from certain political roles, Roy maintained contact as a friend who’d been concerned “leadership review” would cripple Camp’s political future.

The premier understood. He valued Camp’s political assessments, proffered Tuesday mornings over private breakfast at the Park Plaza Hotel, but knew from his own grapevine that the former national president of the PCs was still persona non grata with many Tories. Davis did not protest or urge reconsideration. Dalton ended their conversation saying he just wanted “to write and do other things.”

———

The 1972 national leader’s campaign, with tour maestro John Thompson and the Dirty Dozen advancing Stanfield, made the 1968 campaign’s efforts appear amateurish.

As national tour director, Thompson had Bill McAleer alongside as a co-director; Murray Coolican was their assistant, Gordon Petursson manager, Bev Dinsmore comptroller, and Joyce McEwen secretary. They directed the national tour and ran five separate field teams of regional advance men, each with its own coordinator. The Dirty “Dozen” expanded with fresh recruits; some had no political track-record yet were still keen for action and highly enterprising. For this nation-wide effort, the field coordinators were allotted entire provinces and regions: Tom MacMillan, British Columbia and Alberta; Hal Huff, Saskatchewan and Manitoba; John Slade, Ontario; Richard LeLay, Quebec; and John Laschinger, the four Atlantic provinces. In concert with local PC organizations across Canada, more than sixty volunteer tour personnel would handle Stanfield’s activities off Parliament Hill.

Slade, son of a lifelong Liberal, considered the national tour with Stanfield “quite a move for us, because it involved so much more planning and travel” than the Davis tour around Ontario. DeGeer drew more volunteers from the Junior Board of Trade. MacMillan brought in fellow Abitibi Paper employee Jim Howe.

It didn’t take Tom and advance partner Peter Groschel long to discover that politics in the Pacific province “was pretty much a rat’s nest of competing interests for the Conservatives.” The duo managed to patch together working relationships with politically active PCs such as Tony Saunders and Don Hamilton. The latter ran a radio station and “understood a centralized campaign, something rare.” Mostly, their experience involved encountering locals who insisted on doing the campaign their way.

MacMillan didn’t have to be a psychic to foresee a planned Stanfield rally in Vancouver would be a forlorn assembly in a near-empty hall that television cameras could pan, deflating the national campaign. “They did not have as many bodies on the ground in British Columbia as local organizers thought,” he said. Locals told Tom a thousand people would turn up at Hotel Vancouver. He doubted they’d see even six hundred.

The blue machine advance teams did not always have the option of a good venue, as this cramped stage in a small community attests. Ike Kelneck provides music, Stanfield speaks, television cameramen squeeze in, flags and posters detract from the focus, and local Tory chieftains sit wherever chairs fit.

First of all, the reception was for Stanfield, who was not very exciting. Second, the Conservative Party did not do well in British Columbia, whatever the event. In 1968, the PCs had not elected one MP anywhere in the province. But MacMillan knew pointing out the obvious would not boost numbers, so instead did what advance men are meant to: create conditions for success. “If you get more than six hundred people to the reception,” he challenged, “I will jump into the bay with my clothes on.”

The chance to punish a know-it-all from east of the Rockies was an appealing incentive. They “worked their asses off for the last ten days” and when Stanfield showed up, so did 602 supporters. “They were a long way from one thousand, but would have been a long way from six-hundred if I hadn’t challenged them.” On a cold autumn day, fully dressed, MacMillan took his dive off a pier into the cold waters of Vancouver’s harbour, almost too chilled to hear the cheering. The stunt created a foundation of goodwill for future work among B.C. Tories, as his gutsy reputation spread.

Gutsy advance man Tom MacMillan, by Vancouver’s Bayshore Inn, plunged fully clothed into frigid Pacific waters after boosting numbers at a Stanfield event by vowing to do so if locals could get six hundred people to a reception for the campaigning leader, which they did. The Dirty Dozen’s code was to “create conditions for success.”

At the other end of the country, John Laschinger checked a Nova Scotia community two days before the Stanfield tour was to arrive for a school auditorium rally. He discovered local PCs had erected a big sign for Bob Stanfield. Atkins had been adamant that all advertising and media, including signs, use only R.L. Stanfield. The intent was to achieve prime ministerial gravitas, as in R.B. Bennett. The need was common identity across the entire national campaign. Laschinger ordered the Nova Scotians to get “R.L.” from the sign-maker to fit over “Bob.” They labelled him “the jerk from Toronto.”

In Alberta, MacMillan and Jim Howe found a complete contrast to British Columbia, a province where even the turf was Tory. Of seventeen federal ridings, now increased for the 1972 election to nineteen by redistribution, one was Rocky Mountain where PC candidate Joe Clark hoped to unseat a remaining Grit.

After meeting Clark at his campaign office in Drayton Valley, MacMillan, with Howe and Clark, began walking the streets, accompanied by the municipality’s manager, discussing plans for a Stanfield breakfast as part of the national tour’s Alberta swing. MacMillan noticed loudspeakers mounted on lamp posts everywhere.

The manager explained the system allowed someone to tell the whole town what was going on, just by flipping a switch at the recreation centre. MacMillan immediately saw Radar in the TV series M*A*S*H, broadcasting his announcements throughout the army base. The manager added, “We rent it out.”

MacMillan reached into his pocket, counted out enough bills, and “cut the deal then and there” to acquire exclusive local broadcasting rights for the election. On the morning of the breakfast, “we were able to turn the loudspeakers on and invite the whole town to come on over and have breakfast with Bob Stanfield.” And almost everybody did.

In Edmonton, however, when MacMillan tried to get an ugly wooden graphic representing Stanfield taken down from the arena before a big rally, Roy Watson, an Edmonton insurance broker who ran the northern half of the province for the PCs, realized he, too, was dealing with a jerk from Toronto. “You know, this is Alberta. This is how we do things. We won’t be changing anything now.”

———

It had been early February 1972 when Atkins asked John Thompson to organ-ize a “national campaign tour” for Stanfield. The only guideline was to prepare for the federal election “with some of the philosophy that had been successful in the 1971 Ontario campaign for Davis.”

John convened a tour committee and by March 29 presented its plan to the PC National Executive which approved its two key elements: the national tour would be based in Toronto, and it would have centralized authority over Stanfield’s activities away from Parliament Hill. Not knowing when the election might come, the tour was prepared in segments that could be compressed or expanded.

For the pre-writ period, which turned out to last six and a half months, the initial tour objectives combined close analysis of Teeter’s deep polling research and the need to compile an extensive library of film showing Stanfield in many different settings across the country for media use and campaign advertising. In this phase, Stanfield visited 136 communities, involving 402 separate gatherings. In sixty days of touring, his activities encompassed plant tours, radio talk shows, media interviews, “and all forms of practical campaigning,” said Thompson. To reflect what polling showed as areas most probable for PC gains, the tour spent thirty-three days in Ontario, fifteen in the West, seven in Quebec, and five in the Maritimes. This segment cost $71,000.

Robert Stanfield addresses one of the many large crowds the Dirty Dozen advance team created for him, while a blue machine cameraman films “library” footage for use in PC television commercials.

Over the half year of pre-election touring, Stanfield’s activities shifted from major rallies and nominating meetings to community functions, such as coffee parties, visits to old age homes, breakfast meetings, airport receptions, private meetings, and “issue events” to address aboriginal concerns and pollution problems. By July and August, concentrating on Ontario, major emphasis again shifted, now to hotline shows and plant tours. There was no budget as such for this phase, just a guideline to not exceed $1,500 per touring day. By concentrating on Ontario, Thompson kept expenditures to an average of $1,173 a day.

Once the election began on September 12, leading to voting on October 30, he had three distinct tour phases with different objectives. Phase One would portray Stanfield as a credible alternative to Pierre Trudeau through a tour that was organized, efficient, dynamic, and determined. “We wanted to make the point that Robert Stanfield is determined to be prime minister and that this election is a two-way contest,” said Thompson. The tour team sought to do this “in such as way as to draw out the undecided voters and to ease the fundraisers task.” In the process, more film was added to the PC library showing “good geographical, people, Stanfield, and issue shots.” Attention was drawn “to our first rate candidates across the country.” And in contrast to the PCs’ 1968 campaign, this tour was designed to make Stanfield “look like a winner and thus allow the press to come our way.”

The blitz-like opening in September, touring coast to coast, covered a great deal of territory in short time, included a diverse mix of events. Stanfield was “well received everywhere” because “we went to strength,” said Thompson.

Phase Two, from September 25 to October 17, was expected to be harder, because the tour concentrated on the campaign’s three priority provinces, in Ontario for nine days, and British Columbia and Quebec for two each. Thompson anticipated this intense regional focus would make the tour seem duller, and the press duly complained that it was. All the same, Stanfield registered an impact in the regions visited, which made their ridings more receptive to the PC media campaign. “It was never our objective that the tour would catch fire in these regions,” said Thompson, “only that we would allow for a great deal of participation by the riding organizations and flood the local media with evidence of Stanfield’s interest in their riding.”

During most of Phase Two, Stanfield — reading Camp’s speeches — concentrated on attacking Pierre Trudeau and his management of the economy. This complemented the PC media campaign which started October 7 and continued for ten days, with commercials consisted of street interviews suggesting Canada had serious problems of unemployment, galloping prices, and excessive taxes, and that these were the responsibility of the Trudeau Liberal government.

By October 18, right on schedule with Atkins’s strategy, the PC media campaign moved into its positive phase, as a response to the negatives about the economic problems highlighted in Phase Two. This was accomplished through four waves of commercials: “issue and answer,” “Robert Stanfield the Alternative,” “testimonials,” and “crowd reactions” — all of them upbeat and constructive.

Phase Three ran from October 19 to 28. The tour’s concluding goal was “to demonstrate the strength and substance of the P.C. and Stanfield alternative, as a solution to Trudeau and his government’s mismanagement of the economy.” This ten-day leader’s tour was “going to strength, with due consideration for riding and area priorities.”

Overall, the touring campaign ran for thirty-one days, with Stanfield visits to eighty-five communities and engagement in a staggering 218 events. Stanfield displayed athletic stamina. Tour director Thompson, devoted to spending control given his strong financial training, spent $228,300 of his $230,000 budget, averaging $7,475 per touring day, costed to $2,680 for each community visited and $1,092 per event. He also had a $45,000 budget for tour advertising, of which only $10,200 was used. For transport, the leader’s tour chartered a dedicated DC-9 from Air Canada, and two sets of twin buses. The aircraft logged 69,318 miles (including 10,000 in empty return flights) and the buses clocked 50,000 miles with Stanfield aboard for 8,000 of them.

“No other national political figure in this country,” Thompson calculated, “has travelled as far and met as many people in as many communities as did Robert Stanfield between February 16 and October 30, 1972.”

———

Ike Kelneck’s band, Jalopy, having so enlivened the Davis campaign tour, was indispensible for Stanfield’s.

Jalopy leader Ike Kelneck is at the keyboard, guitarist Roger Perreault is behind the lovely Alice, Reva, and Lynn, all of them performing on a sunny outdoor stage to attract crowds and pique enthusiasm before Robert Stanfield reaches the microphone with his 1972 campaign message.

“They wanted the thing to work,” said MacMillan of the band members. “They wanted people to be in the right mood for Davis because they loved Davis and it was the same for Stanfield. I think they liked all the leaders, in those early days. There wasn’t anything they wouldn’t do to advance the cause.”

In Quebec at a Chicoutimi college, Jalopy warmed up the student audience before Stanfield’s arrival. Kelneck spoke French. The band worked through its extensive repertoire. Organizers at the back of the auditorium gave Ike the signal to “s-t-r-e-t-c-h” the performance, so they kept playing. Stanfield had been delayed. The students enjoyed the upbeat music but were getting restless, after more than an hour. Again, “s-t-r-e-t-c-h” was being signalled. Stanfield’s plane had still not landed. Jalopy, having performed all suitable songs, began playing through their repertoire a second time. “S-t-r-e-t-c-h” signed the advance man from the rear door. Band members urgently needed a toilet break and wanted to rest their raspy voices and sore fingers. They’d been playing over two hours. Students began leaving. Others angrily chanted “Give us Stanfield.” After Jalopy’s two-hour-and-twenty-minute non-stop performance, a harried R.L. Stanfield made his appearance while the musicians fled the stage. “That was our toughest night,” sighed Kelneck.

Integrating Jalopy into the PC campaigns changed the way entertainment fused with politics, enlivened crowds, made everyone more receptive, and created a better environment for the leader. Decades later, Tom MacMillan would look back over his many campaigns and innovations to state that his greatest satisfaction came from “putting Ike Kelneck in touch with the Conservative Party and all the good that came out of that over the years.”

———

Wherever Stanfield spoke, his speeches were exceptionally good: consistent, quotable, and content-solid. Each was the product of a clandestine operation conducted deep in Toronto’s Westbury Hotel.

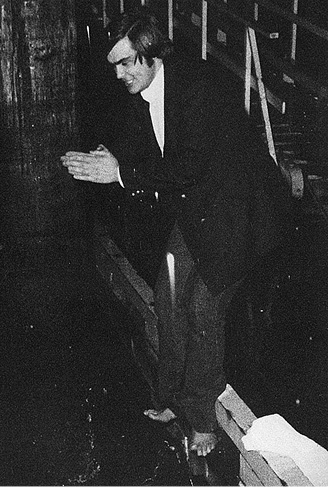

The person writing the words Stanfield spoke, wherever he appeared across Canada, was Dalton Camp. At this stage, Camp was in personal withdrawal from the structured operations of election campaigns, and as a royal commissioner in Ontario also thought it best not to be visible in partisan efforts. But even more, Dalton was now estranged from Stanfield, harbouring a hollow diffidence about being distanced to placate Diefenbaker loyalists. Yet he felt responsible for Stanfield being leader, and still relished crafting political speeches. When Bob asked for Dalton’s help, in a secret face-to-face meeting in a room at the Château Laurier, Dalton had agreed. He was familiar with the scenario, played out from Prince Edward Island to Winnipeg, where a party leader treated him like a married man might his mistress, desired for his remarkable abilities and sophisticated understanding, but kept out of sight to avoid disastrous reactions.

Hunkered down with Camp in his off-the-chart facility in Toronto were Bill Grogan and Wendy Smallian. The place was only known to its three inhabitants and Atkins, Wickson, Stanfield, and Brian Armstrong, who jokingly dubbed it “the bunker,” a counterpart to Norman’s “war room.” Grogan was a seasoned Tory speech writer and senior assistant to Stanfield with whom Camp worked well. They bounced ideas off one another and settled on pithy phrases that packed maximum punch yet were consistent with the leader’s own “voice.” As researcher and assistant, Smallian, who’d earlier worked for PC caucus research in Ottawa, ferreted out damning statistics and dumb statements by Liberals, as requested by either man.

As part of their Château deal, all Stanfield’s speeches would come exclusively from the bunker, to ensure consistency of voice and content. Camp and Groggan’s texts ranged from the leader’s grand vision of Canada’s future to short modules that, like a hand of cards, could be rearranged, played, or kept back for a later round. The speeches incorporated party policy, reflected Teeter’s opinion analysis, and contained Stanfield-like vocabulary.

Here again, as with tour, the PCs were now light years ahead of their 1968 campaign. Then Stanfield had to make up policy, in the vacuum created by the Diefenbaker chasm, on the fly. By 1972, drawing on devoted policy work by countless PCs over many months, the PC leader was able to call for discipline in government spending, more powers for the auditor general to fight waste and inefficiency, and banning strikes in essential services.

Stanfield also announced in his speeches how the PCs would require foreign-owned companies operating in Canada to have a majority of Canadians on their boards; provide a financial incentive for Canadians to invest in small businesses; co-operate with provincial governments in economic development; and emphasize re-training for unemployed workers. His speeches further advocated a range of tax, tariff, and financial measures to address voters’ concerns about the economy, such as increased processing of natural resources within Canada, reducing personal income tax rates 7 percent, indexing tax brackets to inflation to keep taxes from creeping up as the cost of living rose, regularly adjusting old age security payments to offset inflation, and setting up residential land banks to reduce housing costs. Stanfield even said the PCs might introduce price-and-wage controls, if necessary, to control inflation.

Getting these speeches to the touring leader took advantage of a communications machine that was state-of-the-art for 1972. Once Camp and Grogan finished a text, Smallian typed the speech onto the special paper used for an early version of the facsimile machine. The paper was then put onto a roll, the equipment hooked up to a telephone and, as the roll began revolving, exposing the text line-by-line, the rhythm of its clackety-clackety-clackety beat in the bunker confirmed that another Stanfield speech was making its way to some distant corner of Canada.

Wherever Stanfield travelled, a member of the tour carried the counterpart machine which he hooked up to the telephone in his hotel room. Upon receiving the text, he’d hand it to the leader, so Stanfield could become familiar with his speech before going to the public event where he’d deliver other men’s words and make them his own.

This way of creating campaign speeches was new. There was a common “voice” to them all, and consistent development of the campaign themes as honed from Teeter’s research and party policy, which is where Brian Armstrong contributed to the work of Camp and Grogan. They followed the campaign from the bunker, especially watching the television newscasts to see what items got media play, and which did not. This synergistic loop enabled them to refine the speeches and torque Stanfield’s message as the campaign progressed.

Until this point in Canadian elections, a speech writer travelled with the leader’s campaign team, as Camp and Grogan had both done many times, because that was the only way to be in touch with what was going on and to hand material to the leader for his speeches. Absent a speech writer a leader might carry a well-used text and deliver the same message over and over. Sometimes a person might telephone long distance with suggested wording to be incorporated in the leader’s soon-to-be-delivered speech, or otherwise get a note to him, but this patchwork approach, apart from lacking a reliable control system, was open to errors in transmission, especially as the number of people involved increased.

What Stanfield saw, and what he delivered from the podium, was exactly what Camp and Grogan had written and signed off on, consistent with deliberately established party policies.

———

The last of the 264 constituency nominations were taking place.

Ottawa-Centre was such a Liberal fiefdom that not even popular Ottawa mayor Charlotte Whitton had been able to win the riding for the PCs in Diefenbaker’s 1958 landslide. Even so, campaign strategists sometimes entice a prominent person to stand for office in order to add luster to the party’s lineup for national publicity purposes. Those in the backrooms understand the person’s commitment lasts only until election day, after which he or she will resume normal life. The PCs got Edward Foster, a prominent Ottawa lawyer with Canadian Pacific Railways, to agree to be the party’s standard bearer in hopeless Ottawa-Centre.

But Hugh Segal contested the nomination. Supported by young Conservatives from Carleton and Ottawa universities who swamped the nominating auditorium and outvoted others, Hugh became the party’s official candidate.

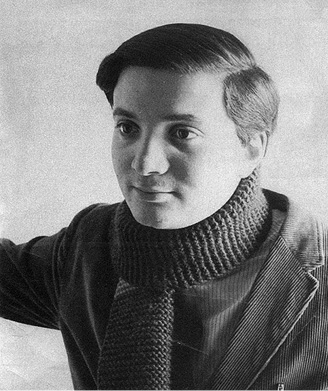

Hugh Segal was a leading PC student organizer at University of Ottawa when he successfully challenged a prominent CPR lawyer for a Tory nomination. Although he nearly won the seat, Hugh never did make it into the Commons, remaining instead in the blue machine backrooms helping elect others.

Atkins was enchanted by this brazen display of organizational ability and, always seeking to “broaden the tent,” as he put it, shone a spotlight on the presence of Segal as an articulate young Jewish person in the Progressive Conservative Party. Several times during the campaign, he called Segal to national headquarters in Toronto “to help on communications matters and do some free-time TV.” The Liberals retained their hold on Ottawa-Centre, but just barely. Hugh came within five hundred votes of breaking through.

———

The 1972 election itself was odd, from start to finish.

The Liberals had surfed into office in 1968 on a crest of Trudeaumania, were still high in the polls, and seemed high on something else, too, with their sweetly mindless campaign slogan “The Land is Strong” and television commercials showing Canadian scenery. With the economy in a slump, Canadians were not looking for strength in the land so much as in political leaders.

The PC campaign, drawing on Teeter’s polling, did not emphasize Stanfield, who’d been found “honest yet bumbling.” Instead, the Tories simply presented a contrast to the Liberals’ drift on economic issues, pledging “A Progressive Conservative government will do better.” The PCs offered a long list of economic and financial measures to benefit hard-hit Canadians; the Liberals had few issues, fewer program details.

The most drama of the campaign came on election night, October 30, 1972, as Canadians became mesmerized by changing vote counts and seat tallies deep into the night. The PCs first held their advantage in Atlantic Canada, Stanfield’s political base, with twenty-two seats, to fifteen for the Liberals. In central Canada, the Trudeau-led Liberals swept his base, Quebec, winning sixty of the provinces seventy-eight seats, while Social Credit picked up fifteen, leaving the PCs with two. Across Ontario, where the blue machine made its most intense push, the hoped-for dividend was paid. The PCs climbed from seventeen seats to forty, taking twenty-seven from the Liberals. Through the Prairies the PCs won most seats, including Alberta’s Rocky Mountain where Joe Clark unseated the Liberal member with a comfortable five thousand vote advantage, including a surge of support in Drayton Valley.

All Canada waited up for the British Columbians, watching as the PCs picked up eight West Coast seats. It was enough. The PCs had broken through, winning more ridings than any other party. Stanfield went to bed as prime minister-elect with the narrowest of minority governments, 109 PC seats to 107 for the Liberals, 31 for the NDP, and 15 for Social Credit.

Overnight, recounts reversed the picture. In two ridings, a bare handful of votes would shape Canadian history. A British Columbia riding just narrowly came back into the Liberal column, putting the two parties at 108 seats each. In Ontario, the York-Scarborough outcome proceeded to a judicial recount and two weeks later, the judge confirmed that PC Frank McGee’s apparent comeback had not materialized. He’d lost by four votes. Thanks to that slim difference, Pierre Trudeau continued as prime minister, his Liberal minority government supported by David Lewis and the NDP.

The outcome deeply chagrined the blue machinists, who’d put on a masterful campaign, but the result corresponded, reasonably well for once, with the popular vote. Canada-wide, the Liberals did have higher support at 38 percent, to 35 percent for the PCs. The NDP’s 17 percent translated into thirty-one seats, and Social Credit’s 8 percent, fifteen.

It was the closest election outcome in Canadian history.