Chapter 39

The Transformation of Bill Davis

In the hollow calm that followed the party’s loss nationally, two blue machine emissaries from Toronto arrived in Ottawa to recruit the national PCs’ director of communications and planning, because Atkins recommended him as “a bright young guy who maybe could be helpful.”

Arriving in Hugh Segal’s office at party headquarters, Hugh Macaulay and Ross DeGeer got quickly to the point. “Would you be prepared to leave here and work for Premier Davis in Toronto in preparing the coming provincial election campaign?”

Segal declined, stating he was “not prepared to leave Mr. Stanfield until he decides whether he is running again.”

Macaulay respected such loyalty to a leader, but was himself more loyal to another, Bill Davis. DeGeer, smooth and friendly but relentless when focused on an objective, was determined to see Davis re-elected. And Segal, flattered at being asked and knowing the next big election would be in Ontario, agreed to Ross’s Plan B: he’d remain officially in his national position but become “a part-time campaign secretary, working directly with the Ontario campaign manager Norman Atkins who had charge of preparing and running the campaign.”

In this role, Segal was soon attending campaign meetings, “making sure that when people agreed to do things, those things actually got done between meetings.” His relationship and friendship with Atkins strengthened as they began working together almost continuously.

Norman, for his part, had gone to New Brunswick after the federal PC loss. From Robertson’s Point, he turned his attention, as communications and organ-ization adviser, to the provincial PC campaign, hoping for at least one victory before year’s end. On November 18, 1974, the Hatfield-led PCs won re-election, giving anxious Norman a needed boost. He’d seen Teeter’s bleak polling numbers for Ontario, where an ominous provincial election loomed.

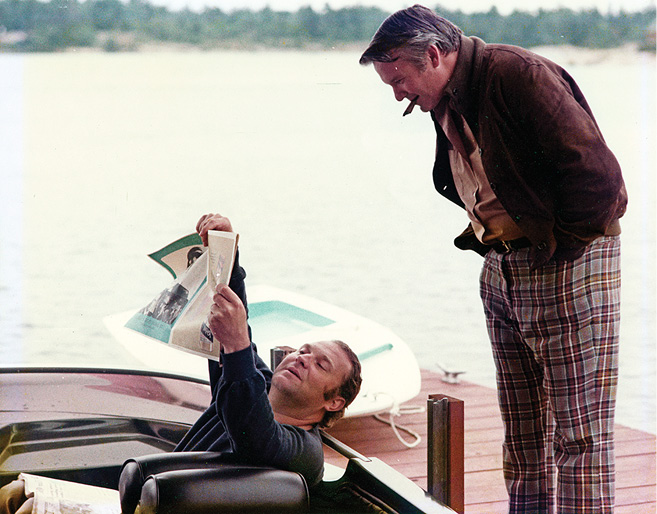

Progressive Conservative campaign chairman Norman Atkins and party leader Bill Davis relax at the Ontario premier’s Georgian Bay summer home, sharing morning news from the political arena. Atkins, at the controls of the blue machine that engineered his provincial campaign victories, worshipped Davis as a political hero.

———

Back in 1971, after the provincial election, Bill Davis and Norman agreed he’d work full-time in charge of the blue machine apparatus. They wanted close links between the PC Party and the Davis government, laying down solid tracks to carry the premier through a successful re-election campaign.

Now Atkins looked at the dire prospects and shook his head. The premier would have to call an election in 1975 but his image had sagged, and so had the PCs’ standing in opinion polls.

Since the 1971 high point, when Davis as a dynamic premier led his government to introduce 150 new legislative measures and program initiatives in as many days, and won a big majority in the provincial election, Tory fortunes had spiralled downward.

Political scandals touching the premier, his ministers Darcy McKeough, Dalton Bales, and Bert Lawrenece, and the inept handling of them, had tarnished the government. Les Frost had peremptorily fired Cabinet ministers Bill Greisinger, Clare Mapledoram, and Phil Kelly for buying pipeline company shares, taking advantage of insider information, and won public support and sympathy for his decisive action to uphold ethical conduct. By contrast, Bill Davis dithered, delayed, and stonewalled when it appeared that conflicts of interest touched his ministry, and lost support for being slow to respond.

The Davis government had been very active on other fronts, yet, ironically, was paying a price for this, too. Protest greeted new restrictions imposed by the government’s environmental plan to protect the Niagara Escarpment. Elsewhere, land-use policies to prevent sprawl of single storey factories and housing subdivisions onto prime agricultural land met opposition from farmers who wanted to become multi-millionaires by selling to developers. The government had intervened massively in Ontario’s regional and local politics, forcing historic municipalities into “regional governments” with new names and little cohesive identity. This generated a third wave of antagonism, this time from displaced local office holders, heritage-minded citizens, and taxpayers underwriting bigger bureaucracies and the higher costs of overlapping jurisdictions, because major sections of the province now had four levels of government: federal, provincial, regional, and local. From Queen’s Park, all these initiatives seemed necessary, but they upset the status quo and, from those directly affected, generated ill-will toward the Davis PCs.

Compounding these problems was the most ironic twist of all: a government resolved to be highly political had become dramatically less so. Davis had revamped the top policy and administrative structure of Ontario in line with recommendations from a Committee on Government Productivity. This committee consisted of senior public servants and business executives, none of them politically mindful. Appointed by Robarts, they reported to Davis.

The committee’s big idea was to cluster departments into what were called “policy fields,” each coordinated by a super-minister. Davis’s top Cabinet members, anxious to be “super-ministers,” got the positions and ever since had been spending their time in meetings at Queen’s Park coordinating policy. Swallowed whole by the new bureaucratic labyrnth, lost in a twilight zone away from operating departments, the most politically astute, ambitious, and articulate senior PC ministers had been sidelined by their own government.

Having disappeared inside Queen’s Park meeting rooms, the top ministers no longer circulated the province to discover what was going on, the task of every politician. Nor were they giving speeches explaining the government’s programs, the leadership task of every politically accountable minister. Indeed, when a few intermittently did reappear in the sunlight to tell Ontarians what they were up to, their speeches were boring expositions about restructuring public administration and government “productivity.” Their focus on policy became how it was processed, not what it accomplished for the people.

This left Ontario’s public affairs field wide open for issue-oriented and eloquent New Democrat leader Stephen Lewis. With a free run hammering at real issues, from mercury poisoning at the Grassy Narrows First Nation Reserve in northwestern Ontario to the paving over of prime farmland in southern Ontario, Lewis and the NDP got media play and won public support. Even the Liberals gained strength, because they too connected to realities upsetting Ontarians in the political vacuum created as the best PC politicians morphed into administrators, playing roles designed by corporate executives and bureaucrats who disdained politics as much as they discounted democratic governance.

Furthering this anti-political process, Premier Davis replaced Keith Reynolds, who’d been Robarts’s deputy minister and Cabinet secretary, with James Fleck, an associate dean of administrative studies at York University who’d been secretary to the Committee on Government Productivity and become wedded to its non-political approach to government. Fleck lacked the instinct for flexibility, compromise, and the free exchange of ideas and information necessary for politics. He understood administration, not governance and accountability. He had no network of friends in the civil service to keep him informed. Under Fleck’s stewardship, Bill Davis spent time in unnecessary meetings with the wrong people while becoming increasingly distanced from his ministers and caucus.

The seed of destruction in the Committee on Government Productivity’s work, now sprouted and nurtured daily, deliberately, and directly by Jim Fleck as the Ontario premier’s deputy, was the hoax that to achieve “modern” government, some abstract private sector idea about “productivity” had to trump politics.

———

The disquiet among Bill Davis’s publicly elected members of caucus, and rumblings by Progressive Conservative Party members who knew Queen’s Park should be the seat of government, not merely the headquarters for its administration or top office of an operation “run like a business,” had to be addressed. The premier also knew that opposition parties, not only his own backbenchers, were increasingly restive about the legislature’s marginalization. He responded by appointing a three-member commission to improve operations of the provincial legislature.

Dalton Camp was chairman. Davis valued Camp’s work as a royal commissioner dealing with Ontario’s beleaguered book publishing companies, and he’d also listened to Dalton’s intermittent suggestions about the need to update the provincial legislature. Having Dalton chair this commission would keep him close at hand operationally, yet at a discrete distance politically. This creative mission would provide Dalton income, and, even more, support his quest to emerge from the political backrooms into a public role for which he was eminently qualified. Davis appointed two other commissioners, for partisan balance and their experience as elected legislators: Douglas Fisher, former New Democrat MP, and Farquhar Oliver, previously an MPP and Ontario Liberal leader.

The Camp Commission’s reports led to fundamental changes. For the very first time, strong rules would govern election finances: limiting donations, restricting campaign spending, requiring audits, and disclosing everything to the public. The Davis government’s 1975 Election Finances Reform Act, based on the Camp Commission’s November 1974 recommendations, was pioneering legislation in North America that completely transformed Ontario politics. The act became a model for election finance laws in other Canadian jurisdictions, beginning with Alberta, which copied the Ontario statute directly, just dropping its more onerous provisions.

Dalton Camp, Roy McMurtry, and Bill Davis confer at the margins of a social event, the Ontario premier’s standard drink of orange juice and rum virtually untouched, also standard. They agreed fundamental reform of election finances was needed.

For Dalton, this transformative change brought the delight of true accomplishment, an enduring legacy. Davis’s decision to act on the commission’s recommendations had lasting effects for him, as well. Although the premier’s dire standing in the polls heightened his appetite for launching a revolution in ethical conduct of campaign finances, it nevertheless took real political courage to reform the role of money in elections. Electoral politics would never be the same.

———

Despite this positive change, the atmosphere at Queen’s Park for the Tories remained negative. Between 1971 and 1975, the news media had become hostile and taken Davis and his government to task over a litany of shortcomings. “The press,” as polite Brian Armstrong expressed it, “had not been kind to Mr. Davis and he had fallen out of favour.” Atkins fretted. DeGeer considered the Globe and Mail “the official opposition.”

In an ill-advised response, Bill Davis even escalated the ill-will. Addressing the Canadian Club in Toronto, Ontario’s premier criticized the Globe and Mail for slanted coverage and critical editorials. “The battle is joined,” responded combat-ready Richard Doyle, the newspaper’s editor.

In 1974, one of the Globe’s reporters at Queen’s Park, Jonathan Manthorpe, who with Ross H. Munro and John Zaritsky formed Doyle’s troika of avenging Press Gallery warriors, published The Power and the Tories, covering Ontario politics since 1943 when the PCs came to power. The book had a Duncan Macpherson front cover showing Davis, successor to the Tory Crown handed down by Drew and then Frost, pulling a blindfold over the eyes of a voter. A substantial part of Manthorpe’s book dealt with the operations of the Davis years.

On balance, it seemed another nail in the Tory coffin. Many PCs felt, as Eddie Goodman put it, “after thirty-two years of Tory power, time appeared to be running out for the Davis government.” The party had lost five straight by-elections under the supposedly astute blue machine. Opinion polls portrayed declining public trust in the Davis-led PCs.

In November 1974, Hugh Macaulay went to see Goodman, the Tory’s highest velocity political operative, at his downtown Toronto law office. Eddie had been on the sidelines the past three years. Hugh slumped in a chair, spoke like a defeated man, and asked Goodman to take over his position as Bill Davis’s director of party organization and adviser.

“I have done everything I can for Davis and it isn’t working,” he sighed, adding he thought Goodman had “the experience and energy to turn things around.”

Eddie knew the timing was all wrong. “It’s impossible for anyone to come in cold from the outside and take charge in the manner required to get us out of this mess.” But he was prepared, he added, “to join the group and work as an assistant to you.”

That “group” was the weekly Tuesday morning breakfast club at the Park Plaza which, Macaulay had informed Goodman, was “the only formal meeting we have.” This advisory committee, he explained, consisted of the premier, himself, Dalton Camp, party fundraiser Bill Kelly, campaign chair Norman Atkins, party president Alan Eagleson, party legal adviser and Davis confidant Roy McMurtry (not yet an MPP), and party executive director Ross DeGeer. Davis having awoken to the urgency of replacing his deputy minister, Jim Fleck, had brought in Ed Stewart, his reliable and politically intelligent deputy minister from the education ministry. Stewart, explained Macaulay, was also now a regular on Tuesday mornings.

Eddie was surprised, when showing up at his first Park Plaza breakfast meeting, that no members of Cabinet were present. He found this high-level group’s composition “clearly an unsatisfactory state of affairs that would lead inevitably to friction” with the elected PC politicians. Goodman knew other major players like Darcy McKeough had to be in the mix. McKeough had returned to Cabinet in 1973 as provincial treasurer, following time in political purgatory after he’d resigned over an alleged conflict of interest.

Whatever value the Tuesday meeting provided in crafting Ontario’s public agenda was offset by the drag it placed on the PCs politically. As word of its operation filtered out, ministers grew resentful about being excluded from the premier’s “kitchen Cabinet.”

The big blue machine, facing an election, occupied political terrain utterly unlike that of 1971. Bill Davis was no longer a political “clean slate” on which the campaign could create an optimal image, but someone with a well-known reputation, and not a good one. The scandals had attracted a bad odour, identified in Teeter’s polling as “an issue of trust.” Ontario was experiencing an economic slowdown. The mood was grim.

Another problem for campaigning, polling revealed, was that no single issue dominated, which would make it harder to galvanize the electorate. Going into the 1975 campaign, Teeter’s research indicated the Davis government was likely going to lose.

“The consternation had reached the point we had to change colours, in a sense,” said DeGeer. Such thinking led to an unprecedented chameleon-like manoeuvre. Ontario’s Tories switched established party colours and changed their logo. It was an advertiser’s brazen ploy: switch identity to remain in office. Elect us, not those other PC guys.

“We ended up with a bilious yellow,” he sighed. “Some people argued we should use what we had in the past — red, white, and blue — but we needed to present a different face.” In part to fool the public, in part to distance themselves from themselves, the blue machine redesigned the Ontario PC logo and switched to blue and yellow for all signs, advertisements, and campaign materials. It was, acknowledged DeGeer, “an effort to be different.”

A sign of just how much control had now passed to the campaign’s central organizers was demonstrated by how, in 1975, the blue machine strove to create the impression of a new party and was able to pull it off unhindered. The practice of polling produced analysis that anticipated defeat; this led to a backroom decision to repackage a tradition-fused party by changing its identity, which, in turn, was followed by imposition of abrupt and unpalatable change upon everyone in the party, province-wide.

———

The election was called for September 18.

Dianne Axmith, by now as much involved in Atkins’s campaign operations as in client work at the agency, located premises for a central Davis re-election campaign headquarters on Toronto’s Adelaide Street, filled it with equipment, and lined up volunteers to run the place. During the election, Atkins and Hugh Segal saved commuting time by sleeping in the permanent Tory suite at the Park Plaza Hotel, where Axmith picked them up every morning, drove them to headquarters, and updated them en route about new developments.

Norman again asked Brian Armstrong to negotiate terms of the televised leaders’ debates on behalf of the Progressive Conservatives, as he’d done for the 1971 provincial election. The PC debate strategy for 1975 was to prevent the two opposition leaders ganging up on the premier. The Tories also wanted to avoid the shouting matches three-way debates often degenerate into, when each candidate, knowing so much rides on the brief encounter, tries to score a point while another is speaking: a noisy contest of voices that turns off most voters. “We wanted to have one-on-one leaders’ debates because we wanted Mr. Davis to be able to take Liberal leader Robert Nixon head on,” said Armstrong of the key point he successfully negotiated.

Teeter’s firm was in the field polling and Armstrong was, in his now customary role, liaising between the pollster and the campaign organ-ization, delivering the results and helping interpret and apply them. Ten days before voting, Davis and the PCs were ten points behind the Liberals. Defeat was imminent.

Atkins called a summit meeting. It took place in Bill Davis’s Brampton home. Joining Davis were Atkins, Armstrong, and Teeter, as bearers of the opinion sampling’s bleak tidings; along with party president, Alan Eagleson; director of party organization, Hugh Macaulay; Davis’s political assistant, Clare Westcott; and chief party fundraiser, Bill Kelly. Everyone was tense.

Downstairs in the recreation room, the premier heard that he would soon go into history as the man who presided over the collapse of Ontario’s Progressive Conservative dynasty.

Eagleson came on exceptionally strong in challenging Davis. He said the premier had to go after Liberal leader Nixon “as hard as he was capable of doing” in their televised leaders’ debate. It was slated for broadcast in just a few days. Davis was reluctant.

Alan was a bare-knuckle fighter, but Bill was not. Eagleson won. The plan was set. Others present reiterated that the losing PC leader had to become more aggressive, but only “the Eagle” advocated extreme fighting. In the coming couple of days, in preparing for the debate, Alan, more than anyone else, got Bill Davis “up” for heavy combat in the two-way debate, the final chance for confrontation before the fateful day of voting.

When the Davis entourage arrived at the CTV studios, the leader was pumped but nervous, and extremely uncomfortable with what he now believed he had to do. He’d been persuaded, in the interests of the party, the government, and the province, that he must do the deed to serve the cause. “He went into that studio and did everything that we asked him to,” said one of those present, “but, boy, was he uncomfortable doing it.” So flustered was Davis that at one point he called the debate’s moderator, Fraser Kelly, a man he’d known well for years as a Queen’s Park senior political reporter, by the wrong name.

Davis effectively proceeded to call Robert Nixon a liar. He said to his face he was running a dishonourable campaign of misinformation and untruth. Nixon, never having experienced Bill Davis like this, appeared stunned. In CTV’s studio viewing room, the PC leader’s wife, Kathleen Davis, watching what was happening, began to weep.

The big blue machine did not rely on this debate alone to turn the tide. Art Collins of Foster Advertising, working in the special PC consortium of advertising specialists, created a number of negative commercials. One of them, which got extensive television play after the debate, right up to the blackout period for paid partisan election advertising, was the “weathervane” commercial. The television ad showed a rooster weathervane turning this way and that, suggesting Bob Nixon just blew in whatever direction the winds pushed him — in short, intimating that he was a man without principles.

Others in the Progressive Conservative Party, traditionally more inclined to follow best practices from Britain, would not have glommed onto these American campaign innovations with the same sly pleasure Dalton Camp and Norman Atkins did. Pollster Alan Gregg, now helping with the campaign, was a strong advocate for the positive effect of negative ads. “They work,” he’d concluded, after tracking polling patterns and election outcomes in the United States.

The first time the blue machine had used negative “attack” ads in Canada was in the early 1970s. The PCs edged into this territory with the 1972 federal election, with advertisements stating “Trudeau Has Failed!” Those TV spots incorporated, said Brian Armstrong, “what we called ‘streeters’ at that time. We had people interviewed on the street about why they thought the Trudeau government was bad for the country.” By the 1974 election, the campaign team pushed this technique by introducing what came to be called “dirty streeters.” The film crew on the street interviewed critical Tories posing as random passersby.

The accelerating trend continued in 1975. For the desperate final week of the Ontario campaign, the hard-edged “weathervane” attack ads ratcheted the ploy a full notch higher. By September 18, it was still uncertain, however, if the combination of a hard-knuckle debate and single-minded negative ads about an untrustworthy Liberal leader would be enough.

On election night, Atkins and Segal were at the Brampton headquarters, with Davis, watching results come in. The premier, it was gradually revealed, would be leading a minority government. Both men circulated the campaign headquarters cheering up dismayed people like Kathleen Davis. “Look, you are still in government. You held on.” A minority looked pretty good to them, based on what they had seen elsewhere, and based on what had been expected in Ontario that day.

The Tories lost twenty-seven MPPs. The party’s ability to retain even a minority hold on power was only due to vote splitting in Ontario’s electoral triangle. The Davis-led party received just 36 percent of the popular vote, province-wide. Some 63 percent of the electorate had voted non-PC, divided 34 percent to the Liberals and 29 percent for the NDP. In a legislature expanded to 125 seats, the PCs managed to win fifty-one, the NDP thirty-eight, and the Liberals, thirty-six. The chagrined Grits, who’d been set to take power, had been relegated to third spot.

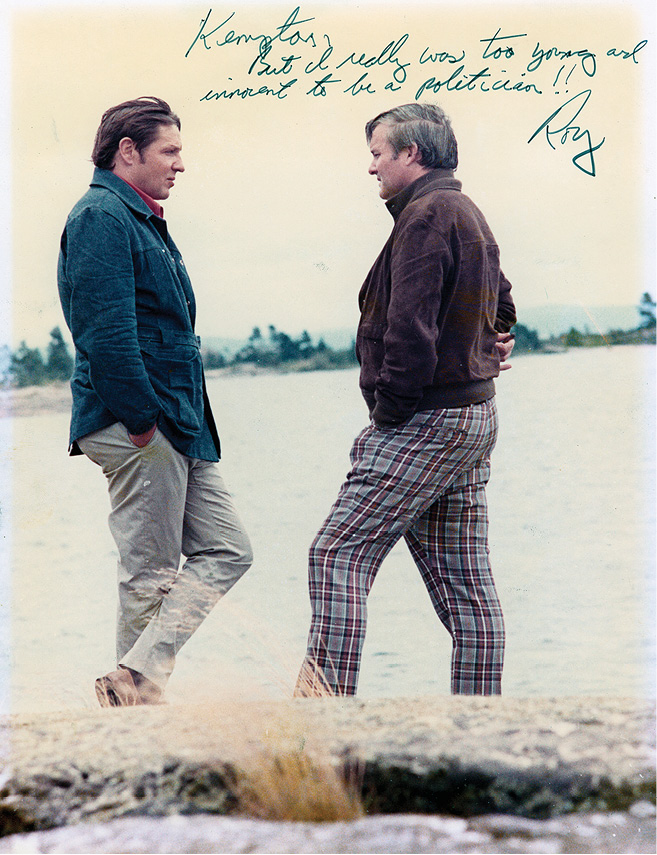

At his Georgian Bay retreat on Townsend Island, Bill Davis keeps up pressure on Roy McMurtry to seek election to Ontario’s legislature. Roy ran and lost in a 1973 by-election, but won a seat in 1975 and promptly entered Davis’s Cabinet. McMurtry inscribed this picture for Norman Kempton Atkins, joking he “really was too young and innocent to be a politician!!”

The PC campaign had a decidedly altered look, with different colours, new logo, and harder edge attacks. Its passive and dismissive slogan, “Your Future. Your Choice” was the best the blue machine brain trust could come up with, believing there was no single issue. The more inspired New Democrats had countered with “Tomorrow Starts Today” and were now the Official Opposition.

———

Bill Davis found himself in the same position as George Drew, back in 1943 when he’d begun Ontario’s Tory “dynasty,” a premier who could be defeated at any time but who nevertheless held power and was grateful to be facing two opposition parties.

Just as Davis had been sufficiently shocked, after almost losing the PC leadership, to take dramatic action by placing his fate with the Camp-Atkins blue machine, he was again sufficiently traumatized, by almost losing the government, to adopt a new way of conducting politics.

His sombre gaze into the abyss of defeat galvanized a political transformation in William Grenville Davis. “He began to reinvent himself,” noticed Armstrong, as sensitive a close-range observer as anyone. “Over the course of the next three or four years, he went from being an embattled leader of a scandal-ridden party to a folksy, bland ‘Mr. Ontario’ personality whom Ontarians grew to love. In the minority situation he became much more at ease with himself.”

That the raw edge of political uncertainty in his daily life and in that of his government should produce a man at ease with himself may seem a paradox. What it really shows is just how deeply imbued with politics Bill Davis truly was. The more he came into his own, the greater his confidence, no matter how awkward or challenging the situation. This enabled him to take a firmer grip on the big blue machine. Bill Davis, with Norman Atkins, would now achieve an infinitely more effective integration of government operations and campaign politics.

For openers, Davis and Cabinet secretary Ed Stewart accepted Atkins’s recommendation that Segal become the premier’s legislative assistant, to help the PCs weather the coming storm as a minority government and enhance direct communication between the blue machine and daily operations at Ontario’s legislature. Segal had been Stanfield’s legislative assistant in Ottawa during the Trudeau minority government, but nobody at Queen’s Park had such experience because Ontario’s last minority government was back in 1943. The Davis government set about to navigate in the legislature and survive, despite having fewer votes than the combined Opposition.

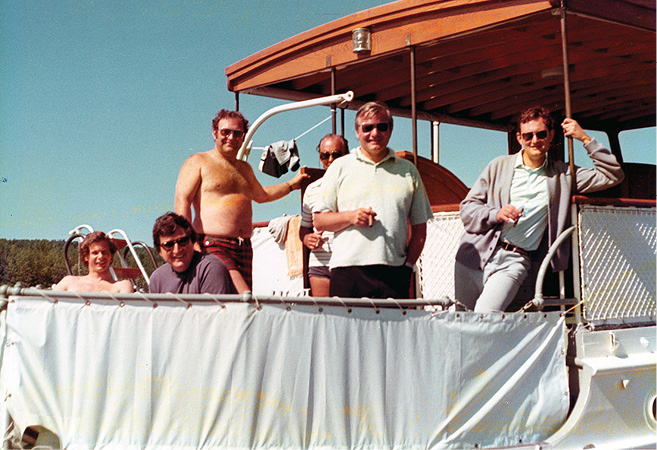

On New Brunswick’s Saint John River heading to Robertson’s Point for a session of blue machinists are, from the left: Bruce Fountain, Ross DeGeer, Norman Atkins, Bill Kelly, Bill Davis, and Brian Armstrong.

Another big change came in the composition of the premier’s Tuesday-morning breakfast group. From the start, Bill Kelly, the Ontario PCs’ fundraiser, was a Park Plaza regular, as was Hugh Macaulay, Davis’s reliable political fixer, and Ross DeGeer, executive director of the Ontario PCs. Dalton Camp had participated until 1975 when the sessions were opened up at Eddie Goodman’s behest to key Cabinet ministers Darcy McKeough, Tom Wells, Bob Elgie, and Dennis Timbrell. Roy McMurtry, elected in Eglinton in 1975, continued to participate, now as a minister. Norman was miffed that Dalton was no longer at the Tuesday breakfasts, and whined about it.

Goodman, one of the best connected Tories, who transitioned easily between the PC Party, the legal community, business and philanthropic worlds, and the Jewish community, and a forceful and effective deal-maker in any backroom, was present and fully accounted for on Tuesday mornings after 1975. From 1978 to 1984, Tom Kierans would also become a Tuesday-morning regular, at Davis’s direct invitation, to provide policy analysis, particularly on economic issues. The premier’s principal secretary of the day was included, successively Brian Armstrong, Hugh Segal, then John Tory. Davis’s deputy minister, Ed Stewart, was never out of sight.

Flowing into this summit gathering were the views of the civil service and the wider political public. Ed Stuart, as Ontario’s senior civil servant in the Cabinet office, distilled the views of the province’s army of public servants to report on the possibilities and pitfalls for any proposed course of action. At the same time, Roy McMurtry and Norman Atkins both had open phone lines and took time to listen to more people in one week than most individuals would connect with over a month, and apart from being extensive, their networks were diverse. Bill Davis’s natural political instincts for balance were rewarded, getting the aggregated and integrated views from all three about handling a matter.

These senior players discussed and shaped significant government policies on a routine and continuing basis, which enabled those running elections, and between campaigns running the party’s media relations, to have accurate understanding of what the PC government was really doing so it could handle the “messaging” and ensure the leader succeeded in maintaining public support for his initiatives. It also helped those in high office, receiving and inwardly digesting weekly field reports from the party’s executive director, to guide the government away from potential electoral difficulties and toward popular stances.

Although this had been the intent of the Tuesday sessions from their inception, by 1975 it seemed no such care had ever been taken, given how many problems the Davis government faced and its declining support. Those days were over. This remix was the make-over of the blue machine’s politicization of Ontario government.

Armstrong witnessed from the centre how “during the testing years after 1975, striving to maintain his minority government, Premier Davis’s Tuesday Morning Group became central to running the province of Ontario.” When Segal came into it, he characterized the group’s purpose as being “to meet on a weekly basis, look at issues coming and going, and make sure that they didn’t get away from the government, and that the government had ample time to reflect upon them. We would give our best advice, and the premier would take that to caucus and Cabinet where the real decisions would be made.”

Yet there was no escaping the inherent problem of how decisions were taken and power exercised. In the eyes of ever more Tory ministers and MPPs, the “real decisions” were reached at the Park Plaza, not at Queen’s Park. With the blue machine so closely connected to Ontario governance at its top levels, initially to ensure that campaign messages properly reflected the intent of goals set by Bill Davis, his Cabinet and the PC Party, it was only a matter of time before the flow reversed. Even insiders like Clare Westcott began to push back, saying it was not appropriate for backroom organizers like Atkins and Segal “to meddle into policy and goals of Ontario’s government and the choices between provincial programs.” Westcott, not part of the Park Plaza Group, was hardly alone in taking exception to the hushed-up existence of the blue machine’s Tuesday breakfast sessions.

“People resented the tight control this group had on power,” said John MacNaughton. “The MPPs and ministers knew that every Tuesday morning a group was meeting at the Park Plaza to set policy, discuss issues, and plot the course of the government and party. They asked ‘What am I doing here, all the work to get elected, so others can make the decisions and I’m a rubber stamp?’” John Tory, when he came on the scene, dutifully played down the breakfast meetings, the agreed-upon message to keep elected representatives onside.

———

Time passed. The government was not defeated. Yet by 1977, two years of minority government “was taking its toll on a lot of people, including the insider volunteers,” said the party’s executive director, DeGeer. “Some people were anxious for an election, but there was no overarching issue that could be turned to our advantage. Nonetheless, we had a general election in 1977.”

Bill Davis engineered the vote because Robert Teeter’s 1977 polling showed the Progressive Conservatives could regain a majority. DeGeer became campaign manager, under chairman Atkins. Segal was on the campaign bus with Davis, enjoying a role he numbingly characterized as “the legislative policy linkage person.”

In this campaign, the still novel “phone bank” got its best workout to date. Ontario’s 1975 provincial election had not yet given enough time to win acceptance of this new practice in most ridings. By the 1977 Ontario election, the blue machine “used the phone bank technique to great advantage,” said DeGeer. “We were light years ahead of anything the Opposition was doing.” It was to be another example, however, where using a new and better method did not translate into more votes.

On June 9, election night, the PCs increased representation by seven seats, still in minority territory, with 40 percent popular vote. The other 60 percent of the popular vote split 32 percent for the Liberals, 28 for the NDP. Polling statistics and the Ontario electoral system, on which the blue machine’s political strategists had depended to their detriment, had confounded them.

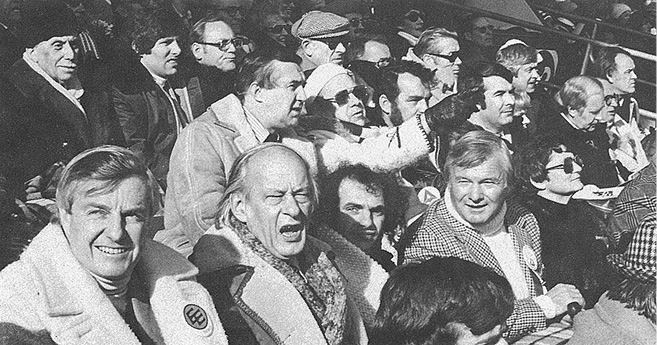

Alberta premier Peter Lougheed, Quebec premier René Lévesque, Quebec youth minister Claude Charron, Ontario premier Bill Davis and wife Kathleen, at Grey Cup game. New Brunswick’s Richard Hatfield is behind Lévesque. For many blue machinists, interest in sports was on a par with devotion to winning political campaigns.

The 1977 Ontario election changed little in the legislature — Bill Davis began and ended the campaign with a minority government — but it sure triggered change within the big blue machine. Disenchanted volunteers went back to their businesses, less enamoured now by politics than they’d been in the heady days of 1971. Changes were made in the caucus office and at PC Party headquarters. Segal departed to John Labatt Limited in London as director of corporate relations. DeGeer moved into the premier’s office as liaison between Davis, the party, and the caucus.

Moving around personnel was not difficult. What was harder to deal with was the polling. “This was the first time in our work with Market Opinion Research,” said Armstrong, intermediary between the pollsters and campaign organization, “that they had been wrong about the outcome.”

Bill Kelly was livid. He’d pulled in all his favours to raise millions of dollars for the campaign, not a pleasant chore when donors were less than enthusiastic about Davis and the provincial PCs, and had, anyway, contributed millions to a campaign only twenty months before. Because of Kelly’s vehemence, the blue machine was now in the market for a new pollster.

“Bill Kelly was absolutely adamant that we had to change pollsters,” said Armstrong. “We had spent all this money on an election campaign thinking we could win, based on intelligence that told us we would, and the intelligence was wrong.”

After the 1977 fiasco, with no resolution about who would be the new pollster, the Ontario PCs did no surveys for a long time. Atkins and others in the federal organization had worked well with Teeter for years, and felt comfortable in the relationship. Kelly remained adamant, however, there’d be no money for an Ontario campaign in which the American pollster was involved.

———

Norman, with Dalton’s counsel, remained involved with PC politics in the Maritimes, including two provincial elections in 1978.

In Nova Scotia, the resurgent PCs claimed a thirty-one-seat victory on September 19, defeating the Liberals, who dropped to seventeen seats, as the NDP advanced to a total of four, in a House of Assembly increased to fifty-two members. Next month, in New Brunswick, where Norman had been communications and organization adviser for an October 23 election, the campaign was what Dalton called “a closely run thing.” The PCs won with thirty seats to twenty-eight for the Liberals.

As for Ontario, with another election possible anytime, Norman insisted Davis ask Hugh Segal to come back from his public relations job at Labatt’s to help prepare the campaign and assist in “negotiating various energy and related matters with the federal government.” Blue machinists held that if a leader wanted someone to work at a senior level, he had to ask himself, so the link was real, the loyalty direct, and the commitment personal, in both directions. Atkins, like Camp, knew from experience that when a party leader asks, people will not refuse.

Segal resurfaced in Queen’s Park as secretary to the Policy and Priorities Board of Cabinet, with the status and hefty salary of a deputy minister. The Policy and Priorities Board, universally known in upper echelons as simply P&P, was the executive body directing Ontario’s government, a more formal administrative body than “the breakfast group” that gathered with the premier Tuesday mornings. Segal’s directing role as secretary of P&P, with clout as a deputy minister officially part of Ontario’s government and public administration, was cover for the fact he’d come back to Queen’s Park explicitly to “prepare for the coming election.” He did so from the very centre of government, remunerated from the public treasury, fusing the blue machine with the operation of government.

While all this provided riveting interest for those in Tory backrooms, the larger national political scene remained an even more compelling source of political intrigues, as well as stunning changes, for Progressive Conservatives.