Chapter 43

Shifting Gears with Brian Mulroney

After winning the leadership on June 11, 1983, Brian Mulroney focused on getting himself into the Commons, which he did within two months through an August by-election of convenience in Nova Scotia. The first-time MP quickly began putting together a campaign team for the coming general election.

Bill Davis urged that Mulroney invite Norman Atkins to head his national campaign. Atkins was the party’s most knowledgeable and successful campaign organizer, with a solid record of wins or well-runs campaigns nationally and in many provinces, Davis reminded Mulroney, who knew it very well. Mulroney also knew the Camp-Atkins blue machine had been in the driver’s seat during Stanfield’s leadership, but not Clark’s, and the only federal election the PCs won, in the succession of five under those two leaders, had been Joe’s win in 1979. But Davis’s strong recommendation carried clout.

Behind Davis’s 1981 win had been the blue machine’s new four-part approach to bellwether ridings, with Allan Gregg’s polling and constituency modelling, the focused K-Tel type television commercials the Camp agency developed, the barrage of direct mail contacts from PC campaign headquarters, and the concentration of the leader’s tour in the swing seats that gave the majority. These prized backroom secrets, of course, would not have been known to someone familiar only with the public results of the 1981 Ontario victory. The federal PC leader weighed his options and made the call to Atkins late in the summer of 1983.

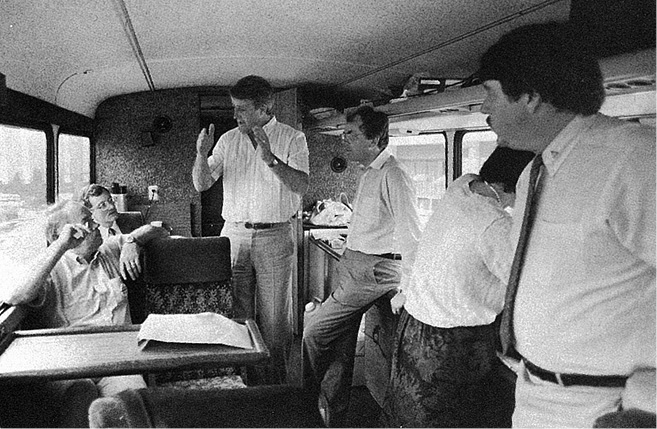

PC leader Brian Mulroney, centre, with 1984 election campaign team at PC headquarters in Ottawa. Mulroney inscribed this photo for Atkins, “Norman, look what we got each other into! Good luck and ‘bon courage!’ Brian”

Immediately after Mulroney asked him to chair the PCs’ national campaign, Norman invited Brian Armstrong to join him at Robertson’s Point. The two Spades sat on the verandah of Atkins’s yellow cottage, talked over roles, discussed the ideal individuals for each, and then filled in the campaign organization chart.

“For a national campaign committee, you are looking at 125 people,” said Paul Curley, who’d chaired the previous national campaign in 1980 and was fully back in the loop with Norman. For 1984, every province established its campaign committee based on the same criteria Norman had, resulting in “a single national campaign organization with ten provincial campaigns replicating the same model.” Norman could pick all those people, said Curley, because he had “an unbelievable network of contacts from which to put together probably the best campaign organization this country ever saw up to that point, and probably ever since.”

To chair the Nova Scotia committee, for instance, he turned to Fred Dickson, his friend from Acadia University who’d worked with him in provincial elections. In Nova Scotia, a single Tory organization existed, so the same people worked in provincial and federal elections, two sides of the same house.

“I followed Norman’s guidance and philosophy and put together a ‘mini-blue machine’ in Nova Scotia,” said Dickson proudly. Mini-blue won provincial elections in 1978 and 1981 and was now gearing up for both federal and provincial contests in 1984. With his friend and mentor chairing the 1984 national campaign, Dickson wanted to be sure his Nova Scotia efforts met the high standards Atkins was known for. “Needless to say, Norman demanded perfection. There were to be no screw-ups; that was for sure.”

More blue machinists were part of the 1984 national PC election effort, and proud campaign chairman Atkins stands with his upbeat and talented tribe of Tory warriors.

For the national organization Norman was assembling for 1984, this professionalism and devotion of Dickson’s machine in Nova Scotia was typical of Atkins’s extended organization in most provinces.

———

By this date, Atkins’s election performances had risen to grand master’s level.

Norman “was like a military general leading the organization,” said Curley, “putting the players in the right spots, providing the overview and broad strategy. Our job was to implement.”

Norman knew what needed to be done, thanks to years of accumulated experience in the army’s logistical operations, campaigns with Dalton, running the agency, and witnessing from his director’s chair the dynamics of government, communications, and events. “He managed to make it so you always felt really good,” said Allan Gregg, “and that you were lucky to be in the room.” He allowed people to nurture great respect for each other. “You were welcome, as long as you performed well.”

He would even whine people into action. Nancy McLean teased Atkins about this way of motivating others, calling Norman’s style “management by whining.” Gregg said, “I would rather say ‘yes’ and not like what I had to do than deal with saying ‘no’ to Norman.”

The organization chart for 1984 was complete, daunting for its high calibre of talent, diversity of people, and depth of experience. But just as there’s a difference between fantasy baseball teams and those playing on real baseball diamonds, campaign organizers can also assemble a dream team on a chart but not get buy-in from the leader. Perhaps some prior run-in, or a suspected character flaw of an individual in the proposed organization, would cause Mulroney to nix a particular choice.

So it was with Allan Gregg.

———

Atkins as campaign chairman and Armstrong as the blue machine’s pollster liaison both wanted Gregg to run polling and strategic development for the coming campaign.

“Yet Mr. Mulroney and his folks were absolutely death on Gregg,” said Armstrong. There seemed to be “an institutional paranoia that infected that group of guys around Mr. Mulroney,” he ventured. Atkins was blunter, calling them “the cronies.” Neither of them had seen such a reaction as from the Mulroney group in politics anywhere before. “The level of paranoia was unbelievable.”

The cronies all thought Gregg “was too close to Joe Clark.” As Armstrong noted, Gregg was a friend and admirer of Clark’s, “and Mr. Clark had brought him into politics and given him his start. So they thought he was a Clark guy.” A related fear about the pollster was Gregg’s collaboration with CBC Radio journalist Patrick Martin and Queen’s political studies professor George Perlin on a book about the recent Progressive Conservative leadership convention and process leading up to it. The book, entitled Contenders: The Tory Quest for Power, had not yet been published when these discussions took place. Since Gregg was close to Clark, and Mulroney had taken the leadership prize from him, the cronies feared some kind of publishing reprisal was in the works.

The main source for this apprehension was Mulroney himself, since he knew better than anybody all that had taken place behind the scenes for him to gain power. “They were absolutely paranoid about what this book was going to say about the new leader of the party,” said Armstrong, who’d begun puzzling with Atkins how to ensure they got Gregg as campaign pollster.

Armstrong met with Charlie MacMillan, a professor at York University who’d become Mulroney’s policy guru. “Norman has designated me, on the organization chart,” said Armstrong, “as the person in charge of research.” They both understood that did not mean policy study but opinion research. Armstrong’s name had been inserted as a proxy for Gregg’s. His real job was to find a way to get Gregg to do the polling research.

Charlie MacMillan, PEI native and York University professor, was a close policy adviser to Brian Mulroney, and both were determined to have nothing to do with pollster Allan Gregg.

“You can do what you want,” said MacMillan in his chippy, direct way, “but you had better not bring Gregg back in here because he is writing a book about the leader and Mulroney just won’t have it.”

The next formal step was for the blue machine to issue a request for proposals to contract polling work for the Progressive Conservatives federally. Armstrong oversaw the competition. At the end of the exercise, Decima, Gregg’s firm, was chosen. Then Atkins and Armstrong had Gregg conduct a poll, the first opinion sampling Decima and the blue machine did for Brian Mulroney.

When ready to present the results, Atkins and Armstrong got together with Mulroney in a secret weekend meeting at the Camp agency in Toronto. As they presented the findings, and especially how Gregg had interpreted the numbers, the aspiring prime minister was impressed. He did not like Gregg, or at least was highly suspicious of him, but could see he needed his kind of talent to win.

Atkins was able to persuade the leader that he could not put together a winning campaign without Gregg’s strategic input, and Mulroney was now able to understand why. As someone who avidly consumed opinion research, Mulroney understood that deep polling would help him determine his tack when trying to persuade others to support his approach to an issue.

Still, it was not going to be easy. Mulroney did not want Gregg’s face seen anywhere in Ottawa, in the campaign organization, even the remotest corner of the party’s most secret backrooms. He did not want to have to acknowledge that Gregg, who’d worked for ill-fated Joe Clark, was now on his campaign. The thrust of backroom appeals made on Mulroney’s behalf by his supporters, when building support for him to win the leadership, was that Brian would be a total change from Joe.

Teeter had to be hidden because he was American, Gregg because he was “Clark,” and in both cases Armstrong was the buffer and go-between. “It was a strange role I had to play,” he said, “first with Market Opinion Research in the early 1970s, now between Allan and the campaign group in the early 1980s.” Gregg did all the work. Armstrong became the face of polling, presenting the results and analysis.

Shortly before Prime Minister John Turner called the 1984 general election, Armstrong appeared at a Wednesday morning PC national caucus of MPs and senators to outline the results of a poll Decima had just completed. Unlike the published polls in the media, which had motivated John Turner’s decision to request the Queen to cancel her state visit so he could call an election, the numbers Gregg’s polling team extracted from people they’d surveyed looked quite good for the Mulroney-led PCs.

Mulroney came across well in the poll for quality of his leadership, ranking higher in a number of categories than Turner. As Armstrong got about halfway through his presentation, Mulroney, knowing precisely what was most important for his caucus to understand, leaned across the head table and “whispered” instructions in a voice intentionally audible throughout the large room, provoking laughter while heightening interest, “Tell them more about the leadership stuff.”

The blue machinists were relieved that the most advanced polling techniques and political analysis would be at their service, despite this cloak-and-dagger hassle. Gregg and Armstrong negotiated the agreement for Decima to do the polling work and all data analysis for the campaign. Gregg would do the same modelling for the country as a whole that he’d pioneered in the 1981 Ontario election, to find the winnable ridings that could give the Tories victory.

———

Another part of Atkins’s dream team was having Paul Curley work closely with him as campaign secretary. Mulroney associated Curley with Clark, too. “I was out of favour with the Mulroney guys,” said Curley. But the PC leader appreciated that the person closest to his campaign chairman would be bi-lingual, and harboured no fears about Curley.

Brian wanted the election campaign run out of Ottawa, a change from the recent pattern of essentially Toronto-based operations, so Norman spent most of late 1983 and the first nine months of 1984 in the capital, living at Finlay MacDonald’s townhouse, where Dalton Camp also stayed when he was in and out of town and where Curley now also resided. Camp and MacDonald were part of the campaign’s “brain trust” helping devise strategy.

Living in Ottawa full-time for almost a year, Atkins left the Camp agency in Segal’s hands, where he remained to take care of business. Norman had brought in Hugh from the premier’s office, after the return to majority government, to be a vice-president of the Camp agency and president of Advance Planning, the public relations and public affairs firm Dalton had started years before, as part of his structured outreach beyond advertising. Advance Planning had languished, with Dalton’s changing interests, and Segal’s mission was to revive it.

During the campaign, Segal’s handling of business at the agency would be interrupted only a couple of times by political assignments from Norman, first to support Brian Armstrong in negotiating the televised leaders’ debates, second to help Mulroney with preparation for the the English-language debate.

As soon as the election was called for September 4, the blue machine campaign team assembled for action. Armstrong left his Toronto law practice and arrived in Ottawa to work full-time in a unit housed at party headquarters, separate from the primary campaign headquarters, with Atkins, Gregg, and Tom Scott. Scott, on loan to the campaign from Foster Advertising as part of Atkins’s backroom advertising consortium, had already worked effectively with Gregg and Armstrong in the 1981 Ontario campaign. Now reassembled, the trio began merging research and interpreting polling results for the national PC media campaign.

Bill Davis again campaigned actively for the federal PCs, as he had for each of Robert Stanfield’s elections and Joe Clark’s first. In addition, he motivated his caucus and the Ontario PC organization to to campaign with enthusiasm for Mulroney. This support was always important in a province electing so many MPs.

Bill Saunderson, after taking a break from campaigns, told Atkins he wanted to get back into the game. Norman named his fellow Spade comptroller for the 1984 campaign. “I was privy again to the Norman Atkins style of meetings,” Saunderson beamed. “They had actually gotten better. Norman had refined his style. The 1984 campaign was classic.”

Saunderson’s work as comptroller carried more gravitas thanks to the election finance law reforms. Now if campaign spending exceeded statutory limits, people could go to jail and election results might be nullified. Saunderson would encounter “some real problems” because members of the campaign team reassured him they were within spending limits, only to turn up in distress after the campaign with a sheaf of invoices for expenses they’d forgotten about “because people didn’t always send bills until the election was over.”

Another part of the 1984 campaign, Brian Mulroney’s inspiration, was the creation of an advisory group of influential Progressive Conservatives across Canada, including Peter Lougheed in Alberta and Bill Davis in Ontario, whom he called intermittently to consult about the campaign. Working the phones had long been a built-in characteristic of the PCs’ new leader. He’d developed a majestic telephone manner, abetted by his rich baritone, calling people, getting information, making them feel included and valued. Each “adviser,” of course, was also a highly influential political player who could, in turn, mobilize campaign resources. Mulroney kept them inspired to take emphatic action.

Mulroney, like Atkins and McMurtry, was a master at reaching out to people this way. “He was thoughtful,” said Curley. “He’d phone someone whose spouse was in hospital, or whose father had died. I’d hear the next day, ‘I can’t believe the leader, with all he has on his mind, telephoned me last night.’”

With Mulroney, the Progressive Conservatives had a leader more adept in the backrooms than anyone before him. Even Joe Clark, who’d grown up in student politics, graduated to roles as a party organizer for the PCs in Alberta under Lougheed, and worked for Camp in party operations at Ottawa and at the agency in Toronto, could not command clout among backroom players to match the engaging demeanour of Mulroney. He was also the first leader of a national Canadian party who really wanted to study polling results, even sometimes the raw data, because he could comprehend the implications for himself. He’d assembled a robust team of loyal fundraisers, delegate dealers, and news media allies to succeed in replacing Joe Clark. Becoming leader of the national party before ever having once run for election to Parliament, Mulroney had well-earned credentials for adeptness in backroom politics.

Other innovations now hallmarks of a blue machine campaign were deployed for 1984. An intensive program of campaign schools for candidate training, and others to instruct campaign managers and official agents, had taken place in advance of the election call.

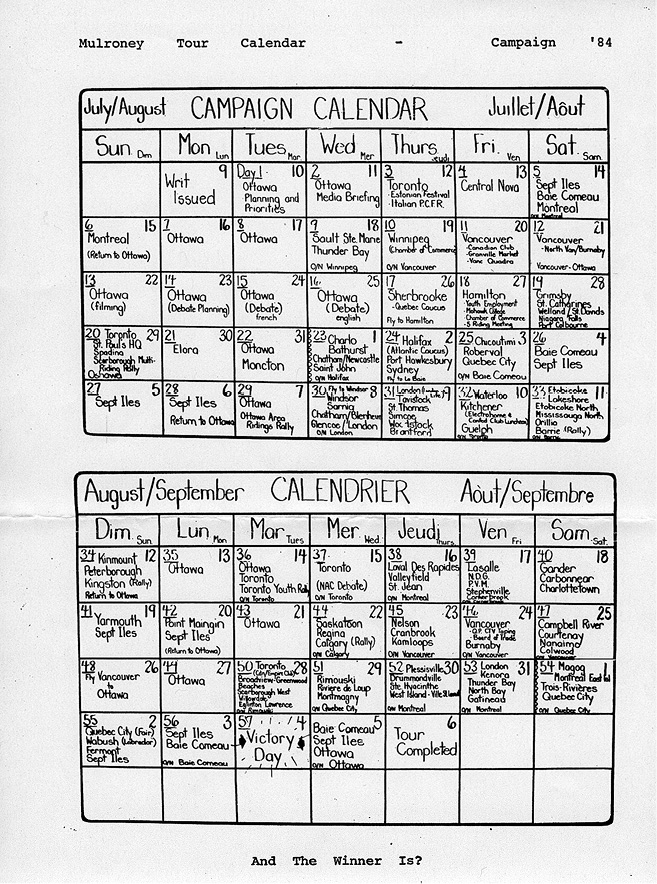

The leader’s tour for Brian Mulroney during July and August in the 1984 federal election was tightly organized, blending polling information with strategic timing for greatest impact, covering all key areas and communities in a sequence for building momentum.

“Every element of the national campaigns in 1984 was probably the best the country had seen up to that time,” reiterated Curley, with “real coordination of all the components of advertising, communications, and polling. Everybody knew what their role was, everybody understood the objectives, and everybody understood who was making the final call — it was the national campaign chairman, Norman, with the support of Mulroney.”

———

The special promise of Brian Mulroney was to break the Liberal grip on Quebec.

He’d campaigned for the PC leadership by asking why Tories should start each election conceding the Grits sixty-five or seventy seats. In the most recent election, indeed, Liberals had taken all but one of the province’s seventy-five seats. Brian’s message was that, as a fully bilingual Quebecer with strong organizational skills, he would change that.

For much of the twentieth century, the default position of the province’s voters had been to take refuge in the Liberal Party, an imperfect bargain because Liberal governments in Ottawa got used to winning these seats and took the province and its elected representatives for granted. But when Quebecers decided to send an electoral message telling Ottawa to stop ignoring them, they seldom turned to the Conservatives. They swung instead to fresher political formations, such as the Bloc Nationale, and the Ralliement créditiste du Québec. On top of that, Conservatives were punished by the voting system. Tories received far more votes across the province than got translated into proportionate representation in the Commons. Judged by its number of MPs from Quebec, the PCs appeared effectively extinct as a party, although often more than a million supporters voted for les bleus. In 1980, their 372,587 votes in Quebec resulted in only one seat in the Commons.

Such long-term voting trends and the electoral roulette of the entrenched voting system made Mulroney’s boast seem improbable of fulfillment. “Le tonneur bleu” or “blue thunder” — the Quebec version of the blue machine — had mounted valiant efforts in Quebec for Robert Stanfield and then Joe Clark in 1968, 1972, 1974, 1979, and 1980, with little to show for the effort.

While the Atkins’s operated blue machine did its best to work with PC organizers in Quebec over these years, Mulroney steadily solidified his own connections and support within the same ranks. All the while, some fine organizers had been drawn into Quebec federal PC activity by Robert Stanfield, and others had developed loyalties to Joe Clark. In the backrooms, if not at the ballot boxes, Quebec PCs were quite alive.

Richard LeLay, Stanfield’s French-language press secretary, was also key with the Mulroney team in the 1984 campaign, and thirty years later, reflecting on those days and consulting his numerous documents of the period, could effectively trace “how the Mulroney victory in 1984 was the fruit born of the particular extension of the fierce determination of the group of individuals associated as ‘big blue’ — Atkins, Lind, Wickson, Curley, MacDonald, Camp, Meighen, to name just those alone.” The essence of the support for the PCs, believed LeLay, was “creation of a strong and motivated partisan membership, an organization directed by effective and performing managers, as well as ideas and a program that was clear, coherent, and articulated.”

Yet on the ground, le tonneur bleu was an operation unto itself, working with Quebec rules, not under Atkins’s control. Brian Mulroney in 1984 was able to draw the personnel of le tonneur bleu into an integrated campaign with two further fighting battalions inside the province.

One was his own team of hardened Conservative organizers who’d loyally carried Brian through two leadership campaigns. Bernard Roy, his close friend since law school, was chair of the 1984 Quebec campaign. Roger Nantel ran all PC campaign advertising in Quebec, quite distinct from that in the rest of the country. Bernard and one or two other members of the Quebec campaign came to Ottawa for national campaign meetings, to ensure the lines of communication were open, but national campaign chairman Atkins was involved with action in Quebec only in connection with the leader’s tour.

Mulroney’s other battalion was the provincial Liberal organization of Premier Robert Bourassa who, for cause, felt abused by Ottawa’s Liberals under Pierre Trudeau and was prepared to send an ally, instead, to the prime minister’s office. This, said Curely, “was a whole different campaign. We didn’t know much about it, except that Bourassa and Mulroney would meet in the premier’s ‘bunker’ in Quebec City” to lay plans, discuss the campaign’s progress, and envisage what might come from a new PC government in Ottawa, which time would reveal to be the Meech Lake Accord, an inspired act by federalist Quebecers to reintegrate their province constitutionally, as PM Mulroney would say, “back into the Canadian family.”

Not only was the crucial Quebec operation quarterbacked by Mulroney, the leader also made sure his loyalists were in key positions throughout the overall campaign structure of provincial committees, too. “But whoever was on these provincial committees,” said Curley, “they all bought into Norman’s plan.”

Ike Kelneck and his band, Jalopy, an integral part of the blue machine since 1971, now raise spirits with Mila Mulroney in 1984. Jalopy had also contributed musical energy to the federal campaigns of Stanfield and Clark, but for the first time had natural stage performers in Brian and Mila.

By the time Mila and Brian were making the leader’s bus tour through the many ridings of populous southwest, central, and eastern Ontario on days thirty to thirty-four of the campaign (August 8–12), a surge to the PCs had begun and they were both in their element joyously meeting and greeting voters.

The campaign plans were agreed to, a clear focus was on winning, yet beneath the surface, perhaps better seen in retrospect than at the time, twinning two campaign organizations, one loyal to Atkins, another to Mulroney, created a deep rivalry within the PC Party.

———

The campaign was only days old when a gaffe threatened to sour everything.

On the leader’s tour, Brian Mulroney strolled to the back of the PC campaign’s chartered aircraft to speak with reporters. They talked about the raft of Liberal patronage appointments outgoing Prime Minister Trudeau required his successor John Turner to make. One of the many was Montreal MP Bryce Mackasey, labour minister in Trudeau’s Cabinet, appointed Canada’s ambas-sador to Portugal. Mulroney, who fancied himself a friend of many in the press corps, misjudged the relationship by seeking to treat them that way. He also erred by thinking that speaking with reporters at work covering an election campaign was somehow “off the record.”

He rambled on about the many appointments and, when asked specifically about Mackasey, became jocular. He was sort of fond of the fellow Montrealer with shared Irish heritage. He quipped that he did not really blame “old Bryce” because as everybody knows, “there’s no whore like an old whore.” He further undermined his own public criticism of Turner’s appointments by adding, as a throwaway line, “You know, if I had been in Bryce’s shoes, I would have been right there with my nose in the trough like the rest of them.” Everyone laughed. Mulroney made his way back to the front of the plane, delighted with the easy, companionable relationship he enjoyed with reporters.

Not all journalists believed that what a leader said in private, when it differed from his public stance, was to be protected by some unwritten rule. Nor were all reporters covering the campaign interested in seeing Mulroney and the Progressive Conservatives win. The “old whore” statement was duly reported and became an immediate sensation. Mulroney’s boomerang delivered a double blow, one hit for the course language used by a would-be prime minister, another for the acknowledgement that he would have behaved no differently from the Grits if able to be a patronage recipient.

The news on television sets in the PC campaign headquarters, set to all channels to monitor coverage in a comprehensive manner, shocked Atkins. The election reports were barely over before he was, Armstrong said, “fielding phone calls from campaign organizers outraged at this development and demanding some kind of action, in response, from the campaign.” Atkins tried desperately to reach Mulroney and the tour group.

When Mulroney called in, Atkins took the phone and lit into the leader with rare vehemence. He described the news story as “a potential disaster for the campaign.” He insisted that Brian apologize for his comments. Only that might help put the issue to rest.

Mulroney resisted. Who was Atkins to tell him what to say? He had been cocooned and did not realize the rapid and far-reaching negative fallout from his very public off-the-record comments. The leader was being told by his press secretary and several “cronies” in his entourage that he needn’t worry because the news story would be “a one-day wonder” that nobody would remember by voting day in September.

Atkins, however, was passionate about the misstep. He would not back down. He insisted on a meeting to discuss it. Camp and MacDonald accompanied him, as part of the brains trust on campaign strategy, reinforcing Norman’s effort to persuade the PC leader, and other advisers with him, that an apology not only had to been made, but offered sincerely.

Brian Mulroney “made very elegant and eloquent apology at a Winnipeg campaign stop at the beginning of the next week,” said Armstrong, “and the issue died an instant death after that.” If things had turned out differently, it would have affected the election outcome in quite a significant way. “If he had not apologized,” it became clear in hindsight, “then he would never have been able to take the high ground so effectively against Mr. Turner in the debates.”

———

Atkins asked Armstrong, because of his experience negotiating terms for the televised leaders’ debates in three Ontario elections, to do the same for the 1984 national campaign, and requested Segal, who’d negotiated out of existence the TV debate for the PCs in the1981 Ontario election, join him.

Alongside Armstrong and Segal were Michael Meighen and CTV broadcaster Tom Gould. The four joined the other parties’ representatives in a downtown Toronto hotel, where CBC hosted the negotiations. What intrigued them most was the impression that John Turner did not want to debate at all. He and his Liberals, after all, appeared to be riding a crest of popularity. In contrast, the blue machine desperately wanted to pit underdog challenger Mulroney against Turner, encouraged by those many “leadership” attributes Decima’s private research kept generating that showed the Tory leader out-distancing the Grit chief.

Shortly before the debate, Armstrong and Gould went to the studio to advance the arrangements, so they could brief Mulroney about the studio set-up, where he would stand, how many cameras there would be, and the location of each. Gould was thoroughly professional about everything, said Armstrong, and “Mulroney was really comfortable working with him.”

When the dates drew near for the debates, Atkins scheduled Brian Mulroney to be in Ottawa at Stornoway, the Opposition leader’s official residence, where Segal, Lowell Murray, Bill Neville, and Lucien Bouchard began covering with him the full range of policies, issues, and tactics.

Meanwhile, the only person to appear at the TV studio on John Turner’s behalf was Israel Asper, dispatched by the Liberal campaign to advance the debate. The talented Winnipeger, who’d led the province’s Liberal Party and since launched into broadcasting with the Global Network, appeared on his own and spent little time looking over the studio or its intended set-up.

Brian Mulroney turned in a masterful performance during the French-language debate, relaxed, eloquent, focused on key issues, and reassuring. He shone even more brilliantly in the English-language debate, delivering his knockout blow to John Turner when the PC leader excoriated the prime minister for making the Grits’ extensive patronage appointments.

“I had no option,” shrugged Turner, suggesting his hands were tied.

“You had an option, sir,” rejoined the Opposition leader, his index finger pointing with stinging accusation as if in a courtroom. “You could have said ‘No!’”

Conventional wisdom emerged that the defining moment in the 1984 election campaign was this nationally televised debate. But for blue machine insiders, as Armstrong said, “if Brian had not apologized and the issue had stayed alive during the election campaign, he would never have been able to admonish Turner on the patronage issue, never have been able to take the high ground the way he did so well.” To Armstrong, “the turning point in that campaign was not the debates, but when Norman Atkins went toe to toe with Mr. Mulroney, told him he had to apologize, then put the people together who could persuade him it had to be done.”

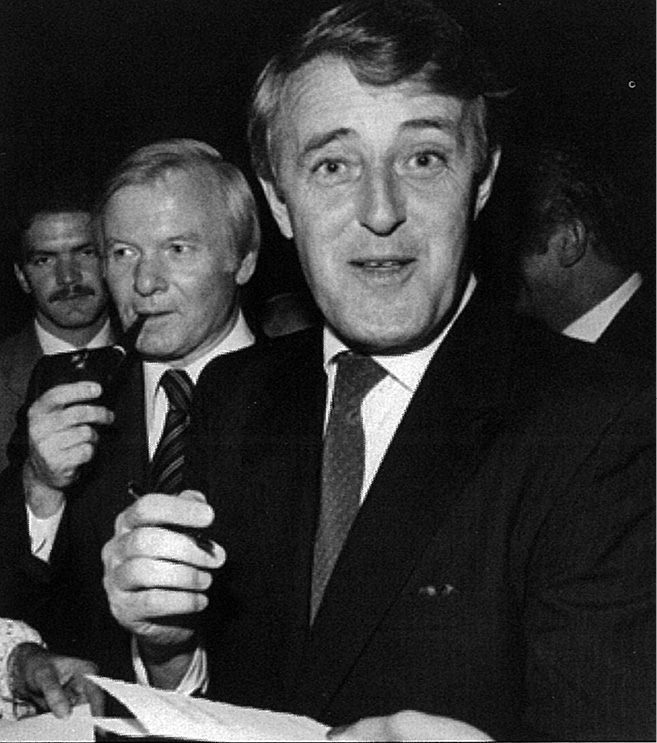

Devoted to the Progressive Conservative cause, Ontario premier Bill Davis fully supports the campaign of national leader Brian Mulroney throughout the province, feeding him the names of folks between puffs on his pipe. Brian is delighted by requests for his autograph.

Following the two televised debates, the PC campaign’s insiders knew Mulroney was on the ascendant, a feeling supported by Decima’s nightly “rolling polls.” Wanting to ensure nothing came unstuck in the crucial closing stages, Atkins assigned Armstrong to accompany the leader’s tour on the airplane, performing anew the role he’d mastered when touring with Joe Clark and Bill Davis in prior campaigns.

At every stop, as directed by Atkins, Armstrong found the nearest payphone and called headquarters to report to Norman directly on how the event went, what the leader had said, and “the temperature of the water.” Brian Mulroney at this stage had his stump speech well honed. There were no more incidents of loose chatting with reporters in the back of the plane or on the press bus, no more need for confrontations over the need for an apology.

———

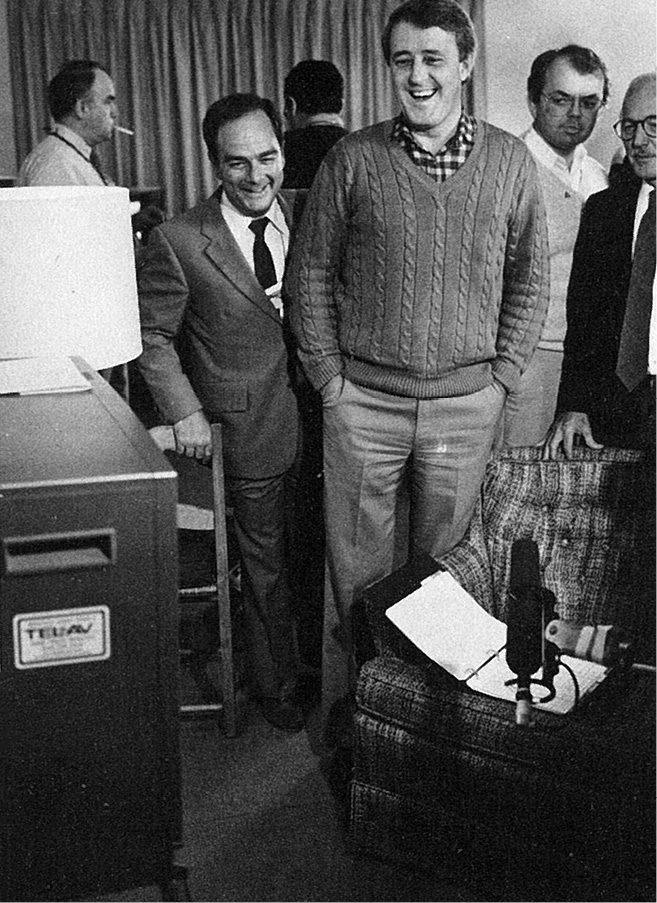

As the results began to be broadcast, PC leader Brian Mulroney and his key organizers watch the televised results and realize he is on his way to becoming Canada’s new prime minister, despite the large lead of the Turner-led Liberals at the start of the campaign.

On September 4, the 211-seat win for the Progressive Conservatives was a campaign triumph for Brian Mulroney and a landmark accomplishment for Norman Atkins and the big blue machine.

Norman Atkins, flashing the “V” of victory, was national campaign chairman for the Progressive Conservatives in 1984 when the big blue machine was at its zenith. His skill, seasoning, and campaign mastery helped Brian Mulroney win the largest number of Commons seats for any party in Canadian history.

The New Democrats, led by Ed Broadbent, remained almost unchanged from the 1980 election, holding about the same level of popular support, around 19 percent, and losing just one of its seats to end with thirty. The real electoral battle had been fought between the Liberals and Conservatives. The Grits plummeted from 44 percent popular support in 1980 to 28 percent, and lost 135 MPs to end up with only forty members in the Commons. The Mulroney-led PCs climbed above 50 percent in popular support and won 211 ridings, a gain of 110 members in the 282-seat house.

With his historic PC majority, Brian Mulroney, a fully bilingual Quebecer leading the Conservative Party, rightly took satisfaction that four out of every five ridings across his native province had elected a PC member to Ottawa.

The national tour included campaigning by bus, a well-honed operation since the 1971 Davis campaign in Ontario. Seated and listening to Brian Mulroney are Pat MacAdam and Brian Armstrong, while standing, Charlie MacMillan and press secretary Bill Fox follow the planning.

To the cheering Progressive Conservatives, campaign manager Norman Atkins, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, and party president Bill Jarvis link hands and bask in electoral glory.