Chapter 44

After the PC victory, Norman, Dalton, Finlay, and their inner circle felt it crucial to forge a strong connection with the government, including the prime minister’s office and party headquarters.

The pattern Bill Davis developed following his big win in 1971, with the Park Plaza Group and Brian Armstrong as his principal secretary at Queen’s Park, offered a model for Prime Minister Mulroney, they believed, to fuse the political direction of his government with ongoing operations of a fully integrated campaign organization. In short, Atkins, Camp, and MacDonald wanted to ensure the blue machine’s operational presence at the heart of Canadian government.

Finlay MacDonald urged the case for putting top campaign organizers and fund raisers in the Senate, a principal role of the appointed house, so they could be in Ottawa, close to the PM and members of caucus, to advance partisan electoral interests while on the public payroll. MacDonald saw himself as a perfect candidate for this role, as did Camp. They got Stanfield to ask the PM to do it. On December 21, 1984, Mulroney named his first senator, a Christmas present for MacDonald. His presence in the Senate secured a beachhead for the blue machinists.

To achieve more direct, hands-on coordination at the top, they had earlier urged Brian Armstrong to consider working in Prime Minister Mulroney’s office as a deputy chief of staff, to function as a trusted liaison between the party’s campaign organization and the PMO. Mulroney had appointed Bernard Roy chief of staff. They envisaged Armstrong as his deputy. Roy and Armstrong agreed to discuss how this might work in practice, and met at Ottawa’s Westin Hotel.

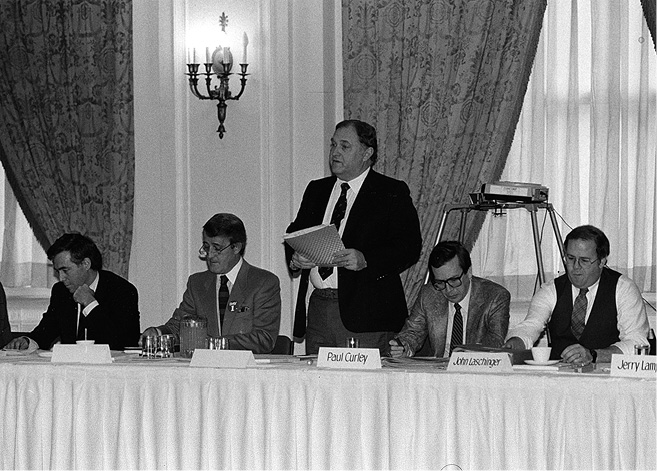

At a Château Laurier meeting, Canada’s new prime minister wears a “Day 1” button as Norman Atkins delivers prepared remarks, alongside PC Party organizers Jean Bazin, Paul Curley, and John Laschinger. At the time, a popular ad campaign for legendary American stock brokerage firm E.F. Hutton was “When E.F. Hutton talks, people listen.” Mulroney, in the euphoric glow of early days, inscribed this goodwill picture, “When Norm Atkins speaks, E.F. Hutton (and their Canadian clients) listen!”

Armstrong began by asking what Roy had in mind. The chief of staff replied he’d not thought about it very much. To fill the void in their conversation, Armstrong suggested he needed to organize the office “on the basis of someone to run the staff and someone external working with caucus and Cabinet on issues of substance to advance the prime minister’s agenda — one staff role, one policy role.” Bernard, however, “saw himself doing both roles and did not know how I would fit in.” When Armstrong asked to see an organization chart, Roy was unable to produce one, even as a sketch. Armstrong never did see one, at any stage.

Learning from his years in the Ontario premier’s office how crucial the structure at the centre is for the complex task of running a government, Armstrong worried that another big Progressive Conservative majority government could implode, from misdirection and confusion at the centre, as it had with John Diefenbaker’s. He spoke with several seasoned players, including Bill Neville, who’d been Joe Clark’s “North Star” as chief of staff and was on the Mulroney transition team, only to learn that Neville himself had been trying to advise about the PM’s office set-up, as well, without apparent interest since Mulroney and his confidants believed they’d get no constructive lessons from how Clark’s office had been run.

Armstrong met with Atkins and Segal, reporting that he feared the PMO “did not know what they were doing” and, most important, Mulroney had not asked him to join his staff. Working for Bill Davis had begun when the premier asked directly. Armstrong “thought it telling that Mr. Mulroney did not make the offer personally.”

Brian and Mila Mulroney host Ontario’s “big blue machine” to a formal dinner at 24 Sussex Drive. Included are Bill Davis, Clare Westcott, Norman Atkins, Eddie Goodman, Ed Stuart, Bill Kelly, Hugh Segal, their spouses, and the Davis family. The elegant celebrations proceeded, while behind the scenes Mulroney ensured he kept the blue machinists from taking too much control.

“If you feel uncomfortable,” said Segal, “go back to law.”

Armstrong returned to Toronto and revived his sagging law practice. In Ottawa, the PMO soon became overwhelmed. Basic management at the centre was lacking. The PM faced a succession of issues, which was normal, but there was a persistent escalation of many of these into crisis or scandal, a situation that, eventually, diminished the PM’s support.

Meanwhile, the blue machine had also been trying to install one of its own at PC headquarters. After the 1984 election, Norman advocated strongly for the PM to appoint Jerry Lampert national director.

Lampert had abundant administrative and organizational qualifications, but Mulroney and his own organizers wanted a Quebecer as national director. Lampert did not speak French, a shortcoming at any time, a fatal flaw for a party finally having solid phalanx of fifty-eight Quebec MPs and strong ground organization in the province. The saw-off was to appoint Lampert and Gisele Morgan, a highly knowledgeable Quebecer connected with the francophone team, as co-national director responsible for Quebec.

The compromise did not hold long. When Elections Canada completed its review of the 1984 financial reports several months later, Marcel Masse was cited for having overspent in his election. Elections Canada notified Lampert it would be making an investigation, and the national director briefed the PM’s chief of staff, Bernard Roy, because Marcel was a Cabinet minister. When the CBC interviewed Lampert, sensing a scandal, he was asked if he’d informed anyone in the PMO and replied that he had. When the CBC asked Bernard Roy, he denied he’d been told. “This put everything into a tailspin,” said Lampert, “and it got very strange.”

This occurred just days before the summer of 1985’s Rough-In, and phone lines buzzed with urgent instructions to Norman and others to “get this thing sorted out.” Quebec organizers who’d been attending the Rough-In in prior years were instructed not to go. Only Jean-Carol Pelletier, who’d grown up on Champlain Street in Baie Comeau with Brian Mulroney, felt secure enough to venture against his friend’s orders. Pelletier, director of PC caucus research, travelled easily between all the party’s factions, even the competitive clusters around Mulroney and Clark.

At the Rough-In, Jerry treasured those “who gave me a lot of support and good counsel and showed the magic of ‘big blue’ in trying to work out political problems together.” The inbound phone messages conveyed from the top that Jerry had to be gone immediately, but Norman pushed back and bought time. He arranged a smooth transition. When Lampert left for British Columbia, Brian Mulroney’s choice for national director, his fearless yet diplomatic friend from Baie Comeau, Jean-Carol Pelletier, moved in. He would remain national director for the next five years.

Long-time PC organizer Jerry Lampert, after a major role in the 1984 campaign, was promoted by Atkins to be new national director of the federal party. Controversy with Mulroney made the appointment short-lived. Here Norman ponders Jerry’s update on the confrontation, and the difficulties of fusing the blue machine with the PM’s own organizers.

“Mulroney came to power as prime minister with a strong core of former university friends and supporters, from St. Francis Xavier, plus a core of Quebecers who were with him for years,” said Lampert. “They were very protective of Mulroney and when they came up against another group, the blue machine that was led by Norman, there were conflicts.” Atkins’s nominee had not lasted. It took a few weeks for Lampert’s phasing out, but “in the end, the Mulroneyites got what they wanted.”

———

In the more immediate afterglow of the September 4 victory in 1984, well before those organizational flaws and power struggles came to light, Atkins and Segal hit Ottawa with a different display of their event-planning prowess.

Four weeks after the Progressive Conservatives swept to power, a two-day conference in Ottawa registered over two hundred senior executives to learn about “The New Government: Players & Priorities.”

The event was Norman’s brainchild. The entity organizing and hosting the conference, Strategic Planning Forum, was half-owned by Advance Planning and Communications, whose chairman was Atkins and president, Segal. In conspicuous circulation was Dalton Camp, now more recognized as a political columnist and broadcaster than former PC Party national president.

The upbeat conference included major speeches on foreign policy by External Affairs Minister Joe Clark, Canada’s economic prospects by Finance Minister Michael Wilson, and the promise of Canadian energy markets by Pat Carney, minister of energy, mines and resources. The roster of speakers also boasted a dozen other movers and shakers from the realms of polling, business, economic organizations, and public service. Although Atkins’s name was absent from the glossy program, he was the one who made the calls, assembled the talent, devised the plans, and personally circulated the rooms ensuring everything from food trays to podium services were just right.

“While the Tory government benefitted from having a friendly platform from which to convey its message to the private sector,” noted political writer Ron Graham, “Strategic Planning Forum took the profits and the publicity.”

———

Also that same fall, Atkins and a hand-picked team of blue machinists worked with Fred Dickson and his “mini-blue” machine in a Nova Scotia provincial election, jointly applying all their best methods. When the votes were counted on November 6, 1984, the PCs climbed to their biggest win yet, with 51 percent of the popular vote across Nova Scotia and forty-two of the fifty-two seats in the House of Assembly.

But by 1987, fortunes would turn in neighbouring New Brunswick for Premier Richard Hatfield. After a dozen years as a popular and progressive premier, he’d pushed the limits of personal behaviour and the five-year constitutional term of office beyond anything blue machinists could offset with a valiant campaign. In the October 13 election, the Liberals, led by Frank McKenna, won in every constituency, getting 60 percent of the popular vote and 100 percent of the seats. The PCs had 29 percent of the popular vote and the NDP, 11 percent, meaning some 40 percent of New Brunswick’s electorate were left without any voice in their provincial assembly, and the government itself was denied the benefits of scrutiny and critique of its measures by opposition lawmakers.

Another exceptional electoral outcome in this period occurred in Ontario, in two stages. In 1985, the province’s Tory dynasty crumbled under Bill Davis’s successor, Frank Miller. “The dumb thing Frank did when he became leader,” Clare Westcott said, “was declare his first act would be to get rid of the big blue machine.” Without the blue machinists, Miller barely managed to win a hastily called general election, emerging with only a minority government. Defeated in the legislature, the PCs were replaced by a Liberal-NDP coalition, which Lieutenant Governor John Aird had accepted so Liberal leader David Peterson could form a government and become premier. The second stage came in the next election, in 1987, when the Liberals won ninety-five of the 130 seats at Queen’s Park, while their coalition partner New Democrats slipped to nineteen seats. The PCs plummeted to third-place standing, losing thirty-six members from the total elected two years earlier, leaving them with only sixteen seats.

As if to prove that Tory support was falling almost everywhere, Nova Scotia PCs headed into a provincial election on September 6, 1988, and dropped fourteen seats to the Liberals. However, they did manage to retain, with twenty-eight seats, their modest majority in the fifty-two-seat assembly, and hence control of government.

None of these provincial outcomes augured well for the Mulroney PCs, as many saw declining support for the federal Tories contributing to the diminishing appeal of Conservatives everywhere, something unhelpful to anxious Norman Atkins, fretting about the national re-election campaign he would chair sometime late in 1988.

———

As early as June 1986, amidst signs of declining PC fortunes, the PM, hoping Norman could reprise his triumphant role from 1984, appointed him to the Senate and asked him to again chair the national campaign.

The campaign’s operational headquarters were back in Toronto this time, but all major committee meetings still took place in Ottawa, drawing on facilities and services readily available in the country’s political capital, and better in every way for campaign meetings with the all-important Quebecers. Each week, Atkins went to Ottawa for these meetings. Segal travelled with him as liaison between the campaign committee as a whole and the Toronto-based advertising, communications, and polling group.

Also working in Toronto with Segal, in addition to Tom Scott who ran advertising and communications, was Allan Gregg in charge of polling, Nancy Jamieson with the group “translating polling into communications,” and Bill Liaskas who created radio and television free-time broadcasts. Together this group also produced all the commercial advertisements.

For the 1988 campaign, Atkins again named Bill Saunderson comptroller. “We did accrual accounting,” he said, to avoid the problems of overspending this time. “As soon as an order was placed, that became an expense,” said Saunderson. “It was on the books as a commitment, deducted from the allowable amount we had to spend.”

Running campaigns at the federal level, Saunderson dealt with a lot of difficult and sensitive problems. “I have to be careful what I say,” he tiptoed, “but all those Quebec guys operated a lot differently than we did, as I found when controlling the money.” Quebec was one of the places the national PC organiz-ation had trouble at the end of the 1984 campaign, but with the lesson learned, Saunderson said, “it was much better in 1988 because Norman had installed people to ensure that we did it properly. He knew that things had to be done right.”

———

The 1988 election, which the PM announced for November 21, became a heated battle over “free trade” with the United States.

Voters often find it hard to distinguish between Progressive Conservatives and Liberals, but never more than in 1988 when the two parties switched policies. In the 1911 election, the free-trade Liberals championed a Reciprocity Treaty between Canada and the United States in a red-hot electoral battle against protectionist-minded and tariff barrier–loving Conservatives. In 1988, the Conservatives fought for the new Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement with the United States while the Liberals opposed it with all vigour possible.

Not only had the parties reversed their historic positions, but Brian Mulroney had repealed his own recent articulate opposition to “continentalism.” When campaigning for and winning the PC leadership, he advocated protecting Canada from American encroachment. Since then, he’d adopted the free-trade recommendations of Liberal Donald MacDonald’s royal commission report, discovering value in accelerating economic flow between the two countries. The PM pulled off this historic about-face without even a debate in caucus.

The 1988 federal election was going to be difficult. Progressive Conservative strategists actually wanted to avoid the free trade issue. “The problem was that while people did not understand its long-term and intangible benefits,” said Allan Gregg, taking the soundings, “the immediate threats of free trade were tangible and real. We did not want the electorate to focus on those liabilities.”

The nationally televised leaders’ debate between Brian Mulroney and John Turner, however, caused them to do precisely that. “The emotion Turner displayed in the debate,” said Gregg, “played a central role in this turn of events. The debate caused people to say that Turner actually believed free trade would threaten Canada’s social programs, and if he feared that, maybe they should, too.”

Gregg’s nightly tracking showed the number of people supporting the PCs had begun to decline, partly “because Mulroney was carrying a lot of baggage,” and partly due to Turner’s impassioned performance in the debate, which the Liberal campaign was repeating in its televised commercials.

Atkins phoned Gregg and stated, with calm simplicity, “We need to figure out how to change this.” They met on a Sunday, after Decima had completed further research and Gregg had done his analysis, including work with focus groups revealing “that the bridge that joined fear of free trade with an increased tendency to vote Liberal was Turner’s credibility, rooted in emotion.”

The counteracting response from the PCs, they decided, had to “play to the innate cynicism voters had toward politicians — ‘Turner said what he said not because he believes it, but because he wants your vote!’” The strategy was to “bomb the bridge” and destroy the Liberal leader’s credibility.

Launching this bridge-bombing campaign, Canada’s finance minister, Michael Wilson, said brazenly in public that John Turner was “a liar.” Willard Estey, “the grandfather of Medicare in Saskatchewan” and a distinguished lawyer who’d just retired from the Supreme Court of Canada, said unequivocally that free trade would not put healthcare in jeopardy. These and other statements formed the basis of the blue machine’s campaign to destroy Turner’s credibility.

“We used ‘streeter’ advertising that employed real voters voicing their disbelief of Turner’s motives, together with very tight shots of Turner’s face. We hammered away,” said Gregg. “The numbers stopped going down, and then reversed.”

What was stunning were the number of PC advertisements, more flights of television ads after the televised leaders’ debates than ever seen before, “aimed at people who stayed home and watched shows like Oprah Winfrey and such, because they were the people our polling told us were undecided,” said Segal. Many people on the bus with the leader’s tour, including the journalists, never saw the ads because they were travelling, “but the voters we needed to get to were carefully reached in the campaign and craftily put together on that basis.”

The drama was explained by Gregg, who said when he’d “first started on the knee of Norman Atkins, he talked about ‘the rule of eight.’ You could never manage more than eight points of popular-vote shift over the course of a campaign.” The 1988 election had two fifteen-point swings. Mulroney and his candidates lost support going into the campaign, and again after the debate. “We lost it twice and won it back twice during that campaign,” said the Tory pollster.

In this see-saw campaign, the PC response, which focused on John Turner’s “Ten Big Lies,” came from polling research “that kept telling us that people misunderstood free trade,” said Segal. “What John Turner and others had been saying made people believe free trade was about American guns flooding into Canada, about giving up our water to the United States, about doing away with Medicare.”

The tabloid newspaper, Ten Big Lies, was prepared by the PC campaign, under Norman Atkins’s direction, with content prepared by Harry Near, and Segal contributing based on Gregg’s research. With lightning speed, bundles of the tabloid were distributed in all major urban ridings across Canada, at bus stops, subway stations, and any public place people congregated or travelled in large numbers.

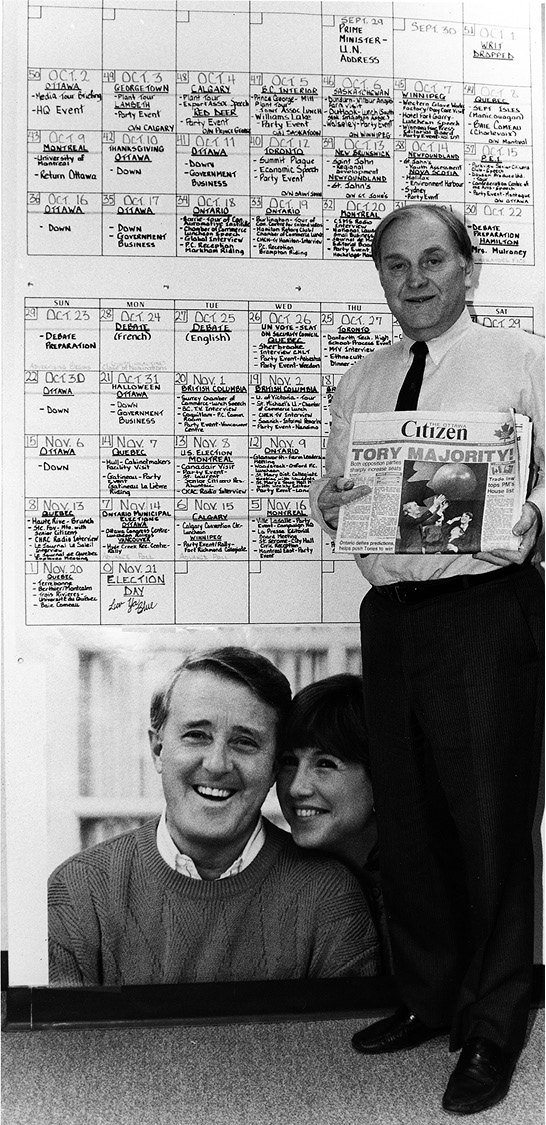

The morning after the Mulroney PCs win a second majority government on November 21, 1988, national campaign chairman Atkins, standing beside a blow-up of Brian and Mila and the leader’s campaign itinerary, holds up the Ottawa Citizen with the headline “TORY MAJORITY!” The front page includes a story, “Ontario Defies Predictions, Helps Push Tories to Win.”

The newspaper’s blunt message was supported by a series of campaign television and radio ads in which Simon Reisman, who’d been John Turner’s deputy minister, talked about how Turner was “wrong on free trade, probably lying.” Mr. Justice Emmett Hall, whose major public contributions included extensive support of Medicare over many years and chairing a royal commission on medical services, was heard by Canadians saying he had read the Free Trade Agreement “and there was nothing in it that would hurt Medicare in any way, shape, or form.”

According to Segal, the Ten Big Lies was part “of one of the most remarkable comebacks after the infamous debate in 1988. We went from six points ahead to fourteen points behind across the country, and could have very easily lost that election, had the Ten Big Lies comeback campaign not been put in place.”

When the Mulroney PCs won a second majority government, with 169 seats, Allan Gregg attributed it “to Norman Atkins’s hand on the tiller. He put the keel deep enough in the water to stay the course.” Normally, when you get into campaign trouble, he added, the first thing that happens is your detractors cut and run. “They say the advertising is bad, and so forth. There was not one word of panic at all during that campaign.”

Of some fifty election campaigns Gregg worked on, he classed two as “the most exceptional” — the Ontario 1981 election as “the most technically advanced and sophisticated,” and the 1988 national election as “the most brilliant.”