Chapter 46

The Blue Machine Faction

The big blue machine was a faction among Canadian Progressive Conservatives.

It was unlike other factions that rise and fall over time, those grouped around a fresh policy orientation (like the progressive Port Hopefuls in 1942), or a plot to gain power (like the Four O’Clock Club of Diefenbaker’s ministers who tried overthrow and replace Canada’s prime minister in 1963.) It was, uniquely, a faction devoted to winning political campaigns.

The blue machinists were skillful, hardened, diverse individuals held together by a code of performance and a bond of human affiliation. They were more akin to a sports team or squad of commandos than a typical political organization, although winning power, not claiming a trophy or seizing an installation, was their mission. Blue machinists included Tories of long standing, converts from Liberal ranks, and apolitical inductees who embraced the brand and its projects more for adventure than because of attraction, at least initially, to the philosophy of Canadian political conservatism.

One hallmark that ensured they would remain a faction was their embrace of slick campaigning. Being “slick” in politics is tricky. A pejorative meaning suggests “a slick character” might be a cheat, a term you’d never want applied to your party’s candidate or office holder. A different sense of “slick,” however, is exactly what a campaign should be: “dextrous, not marred by bungling, carried smoothly through.” Ross DeGeer smiled with pride describing the blue machine’s convention campaigns for Bob Stanfield and Allan Lawrence at Maple Leaf Gardens as “very slick!” Yet that slickness dismayed voters, distanced journalists, and even caused many Tories who benefitted from it to recoil.

“The very thing that personified success,” said DeGeer about this irony, “became the issue against us. While the U.S. influence and slick campaigning that went on in 1971 was the reason for our success, it was used against us with great effect. We were being chastised and criticized during the campaign for being ‘too slick.’ Even though we knew that slick works.”

That quest for slick performance was like a bonding agent for those who hung together as operators of the machinery. On October 21, 1981, on the tenth anniversary of their Davis 1971 campaign victory, the Dirty Dozen threw a dinner for themselves at the Albany Club to honour their own accomplishments and celebrate “A Decade of Slick.” Their guest of honour was American Jerry Bruno, legendary advance man for the Kennedys, whose book of tips for running campaign tours had become their bible.

“We celebrated. We thought we were good. We knew we were,” said John Laschinger. Down to minute details, the celebrants had planned their event with the same attentive skill they’d deploy on a major campaign event. The evidence of being professional, or “slick,” was everywhere — from the prestigious room chosen at the historic Tory club, to the professionally designed glossy printed program, savvy choice of menu items, and finely tuned speaking arrangements. Specific limits of time had been allocated for each individual. A Decade of Slick was their spotlight event to illuminate what the campaign business was really all about.

“The purpose of an election campaign is deadly serious,” said Laschinger, one of the seasoned backroom warriors present. “But we also make campaigns fun, professional, and exciting.”

These blue machinists celebrated themselves because they believed they were the best. The night grew long as after-dinner drinks flowed. “We had fun celebrating our success, not caring what anybody else thought.” Everyone spoke well past their allotted time, “and told b.s. stories.” It was an odd mix of smugness and sincerity. In that room were dedicated specialists who’d come to love the electoral game, most of them never having done more than vote in an election before being recruited by Norman Atkins, Ross DeGeer, or a friend who valued their talent and character for somebody’s campaign.

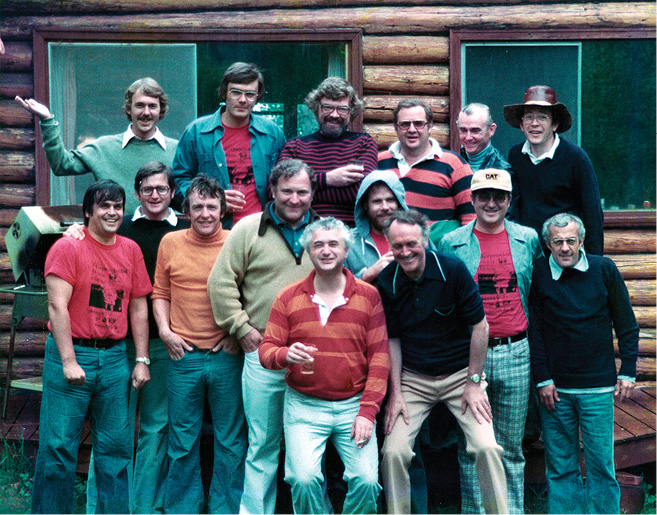

On October 21, 1981, the blue machine’s Dirty Dozen threw a dinner for themselves at the Albany Club to mark ten years since the Davis election win in Ontario. Front, left to right, are Ross DeGeer, Gord Petursson, legendary American advance man Jerry Bruno, who was their inspirational role model, John Shepard, and Paul Curley. Rear, l-r: John Laschinger, John Slade, Norman Atkins, Tony Stampfer, Bill McAleer, Bill Neish, Malcolm Wickson, Brian Armstrong, John Thompson, Tom MacMillan, and Peter Groschel.

They believed their electoral work indispensible for a democratic society. “It was our chance to make a difference,” said another of the advance men. “Our fathers were not in politics.”

———

The original members of the blue machine had been drawn like disciples to Dalton Camp, a luminous presence in a Tory wasteland. As time passed, they and additional recruits were kept together by Norman Atkins’s ability to spot talent, turn individuals into a team, and foster, through them, the ambitions of his brother-in-law.

Conducting this work full-time and to the exclusion of normal family life, Atkins became as devoted to it as might a grand master to the workings of a secret fraternal lodge. Norman kept lists of the faction’s members, identifying the separate units of the Camp-Atkins political machine: the Eglinton Mafia, the Spades, the Allan Lawrence Leadership Campaign Team, National Club Group meeting with Bill Davis, the Restaurant Group, the Park Plaza Group, the ’71 Ontario Provincial Election Team, the Dirty Dozen, the ’72 Federal Election Team, the Robertson’s Point Interprovincial Tennis Classic & Rough-In, the ’74 Federal Election Team, the ’75 Ontario Provincial Election Team, the ’77 Ontario Provincial Election Team, the Albany Club executive, the ’81 Ontario Provincial Election Team, the ’84 Federal Election Team, Blue Thunder, the ’88 Federal Election Team.

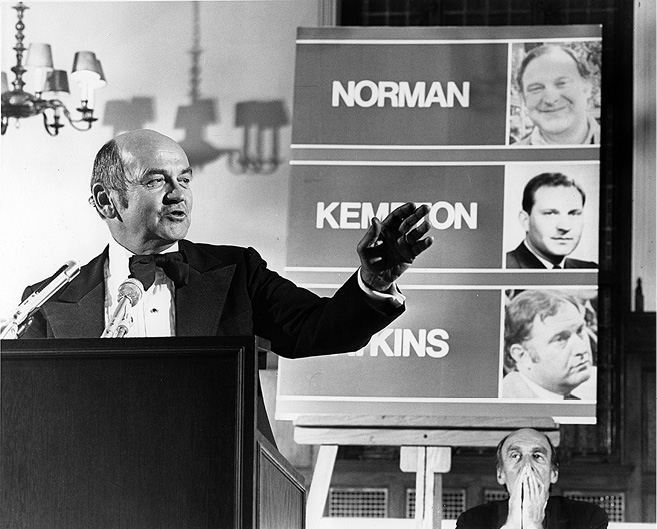

Those whose careers were intimately entwined with Norman Atkins’s gathered at the Albany Club to pay tribute to the engineer of the blue machine. Dalton Camp speaks with humour. Waiting his turn (lower right) is a pensive Robert Stanfield who, by this date, regretted having distanced himself from Camp and Atkins to curry favour with the Diefenbaker loyalists.

Each campaign formation was a hand-picked group, a fraction from the whole. Such exclusivity brought important benefits to the blue machine, but separate status also guaranteed never rising above being a component within the Progressive Conservative Party. Being in the blue machine was never about being a Tory, but about being part of a group that made Tories successful.

Norman, a maestro of clubiness, knew he could best promote his code of “loyalty, friendship, and communication” by a shrewd and companionable mixing of diverse individuals. Special shared identity as part of the Eglinton Mafia, or the Spades, or the Dirty-Dozen would impart a deeper hold, beyond mere party affiliation.

He expressed this through the Rough-In, to which women began to be invited, just as he took a driving role to have women admitted to membership in the Albany Club, on the basis that loyalty to the PC cause was not gender restricted. Among those he invited to join the formerly all-male Rough-In were Jodi White, Diane Axmith, Elizabeth Roscoe, Kellie Leitch, Marjory LeBreton, Effie Triantofolopolus, Gina Brannan, Joan Peters, Nancy Jamieson, Rita Mezzanotte, and Jocelyne Côté-O’Hara. The first year women came, an earring was added to the Camp-like character in the logo, and the image printed on white sweatshirts for all participants. Blue machinists always appreciated a nice touch, and some humour.

As the event’s reknown spread throughout Norman’s larger tribe, the number of invitations climbed and the Rough-In outgrew the Robertson’s Point facilities. The gathering then rotated through different, larger venues in Quebec, Ontario, and Manitoba. By the early 1980s, Norman needed to accommodate some seventy-five of his top political operatives, so made a deal with one of his Ontario organizers, Art Ward, who owned Wigamog Resort in Haliburton. With three tennis courts, a tennis practice wall, two pools, and a lot of card tables, Wigamog remained the Rough-In’s venue for the rest of the group’s days.

Whatever the location, Norman brought in new players each year to strengthen the network, including its Blue Thunder section in Quebec. Rodrigue Pageau started coming in 1980, sharing some of his techniques that would make him a highly effective double-agent organizer for Brian Mulroney’s leadership campaign while appearing to be organizing for Joe Clark. Marcel Masse, already prominent in Quebec provincial politics as a leading Union Nationale minister and later a key Mulroney Cabinet minister, joined in. Richard LeLay was another regular, as was Jean-Carol Pelletier.

The growing roster of attendees was important for cohesiveness of the blue machine. Norman fostered team camaraderie among individuals who’d never met before. The common denominator of all, said Paul Curley, “was their admiration and loyalty to Norman.” When a political campaign approached, “he had many who would willingly and quickly respond to his request to help.” The Rough-Ins “became a breeding ground for campaigns.”

In the early 1970s Norman Atkins gathered his core team at Robertson’s Point for a guy’s weekend that included tennis, grilled steaks, drinks-in-hand, and politics.

Each year more blue machinists, keen for a coveted invitation, turned up for Norman Atkins’s tennis classic and PC campaigners Rough-In. Each year a different logo-imprinted sweatshirt was issued, but every year Atkins — a former New Brunswick tennis champion — claimed the trophy with his intensely competitive play.

The “classic guy’s weekend” became co-ed when women were invited, about the same time the Albany Club admitted women members. The sweatshirts issued that year were white and the Dalton Camp–like figure of the logo got an earring.

The tennis was hard-hitting, the ribbing by the attentive spectators even harder. John Tory and other blue machinists watch play, relax, chat, and hurl comments at Norman Atkins who, despite hosting the Rough-In, was resolved to beat all comers, and did.

Those participating acquired a sense of communal belonging and strong belief they shared a cause important to Canadian democracy. Mixing people for meals, conversation, tennis, entertainment, drinks and debates, melted divisions between them and created an ideal method to transfer expertise. For a person who had managed ten campaigns, or done the advertising for them, or run the media buy for them, or conducted the leader’s tour for them, to hang out with a younger person wanting to get more involved in electioneering and explain how all that works after a couple rounds of tennis and over a beer, was, said Segal, “a rare and wonder-filled opportunity.”

———

Some names run consistently through most of Norman’s groupings of blue machinists, his own in them all. His lengthy list of Quebecers in Blue Thunder was “subject to change,” as if Norman was unsure of just how the Quebec-based projection or affiliate of the blue machine operated, or was even constituted, because many would be seen by Joe Clark and by Brian Mulroney as being part of their team of organizers, not Dalton’s and Norman’s.

A second revelation is that the names of various individuals who’d been instrumental (his tested friend Paul Weed, for example) were crossed out after Norman cut them adrift, like retouching a photograph to remove a person from history. Also, others who’d participated in key events were omitted from his lists, perhaps through a failure of memory, or clerical error, but, likely, just because those individuals considered themselves more a component of the blue machine than Norman ever did.

Most surprising of all was the fact Atkins’s records, as he kept them after reaching the Senate in 1986, only focused on Ontario and Ottawa in the 1970s and 1980s. Although Norman was himself at the centre of the blue machine, and had matured as a young man amidst its origins and evolutions in the Maritimes, he’d started to envisage this special Tory faction narrowly in time and geography. Spinning his rewrite of history, the senator prepared a memorandum asserting “the big blue machine really got its start with the Spades.” That happened in 1966. He’d forgotten about coming back to Canada in 1959 from military service, showing up at the Camp agency for a job that blended advertising and campaign organization, and Dalton’s work as an organizer and campaigner in the 1950s that was the foundation for all that followed.

Norman had changed his citizenship and the name he went by. Why not change the creation story? If spies are licensed to kill, admen are licensed to spin.

The truer narrative is that everything Norman Atkins was able to do politically was built on the innovative campaign work Dalton had engaged in since the 1950s. This included election wins in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, significant connections in Manitoba during the Duff Roblin years, the various campaigns involving John Diefenbaker, and making Bob Stanfield national PC leader against very long odds in 1967. Norman increasingly became part of all that, not just by following and expanding Dalton’s methods but also by absorbing and applying Dalton’s insights and values.

It was in New Brunswick where the first PC win came, that the first government advertising contract had been proffered, where the pattern of close personal interaction in casual settings with party leaders began, and the Rough-In was launched. Robertson’s Point, from the beginning, was to the blue machine what the Montreal Forum was to the Canadiens hockey club in the glory years of repeated Stanley Cup championships.

———

So the blue machine was more. But it was also less.

As a faction, and a generally secretive one at that, the blue machine was not as broadly representative as the party itself, nor could it embrace all the diversity found throughout the far ranging Tory domain. The independent PC dynasty in Alberta was proof of that, and so was the edgy coalition with Mulroney’s ground forces in Quebec. The blue machine was never designed to be a welcoming big tent. It was always just a faction because that larger umbrella function remained the exclusive role of the Progressive Conservative Party, to which the machine was connected as a tightly disciplined backroom operation.

Secrecy was essential to the blue machine’s nature: plotting how to beat Grits and win power was something Liberal informants sought to find out about, as did persistent journalists, so guarding against spies and leaks was imperative. That very secrecy, though essential to its operation, caused resentment and suspicion within the PC Party itself, feelings that over time would be the blue machine’s undoing, as Ontario showed. The large majority of Tories who were not at the machine’s controls began to see themselves as pawns rather than players: Cabinet ministers excluded from the Park Plaza Group, MPPs and candidates whose speeches, signs, and schedules were centrally determined by the blue machine’s war room with no input from them.

———

Another feature of this political machine is that the renown was larger than the reality. Both Camp and Atkins were in the advertising business, and exceptionally good at it, so understood how it advanced their purposes to be seen, not as fallible humans, but as men operating a superhuman “machine,” which is how their strong and innovative operation impressed reporters and rivals alike at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1967 and again in 1971.

Clare Westcott certainly exaggerated when he dismissed the machine as “a fiction.” Jerry Lampert, the political organizer who briefly became PC national director, came closer to the mark in talking about “the mythology” of the big blue machine. Early on, after the 1952 PC breakthrough campaign in New Brunswick, Dalton the giant-killer was savvy enough to chuckle about “the myth of my own reputation.”

Nobody knew better than Atkins, the advertiser adept at making something larger than life, the importance of perception. At the start of the 1984 election, the national PC campaign chairman gathered his political operatives at the Albany Club to talk about the campaign plan and about attributes of political loyalty. He concluded by exhorting them, about the big blue machine: “Remember, we have a mythology to live up to.”

Lampert in that campaign was co-director of operations with Harry Near and witnessed the machine at peak performance. While Near handled the practicalities of the leader’s tour, Lampert liaised with all ten provincial committees, travelling the country, ensuring they had whatever was needed to run successful campaigns, acquiring in the process a rare overview of the machinery’s parts. “There was a lot of mythology around the ‘big blue machine’ and what it was and how it operated,” Jerry concluded.

“At the end of the day, it was a very small group of people who just rolled up their sleeves and got the job done. People had the impression the machine was thousands and thousands of people rushing out to do the job of electing Davis, or whomever. It had a lot of volunteers, but a small group really made it work. The mythology grew out of that, because it was successful.”

———

The blue machine was neither a fiction nor an invincible enterprise.

The reality is that it enjoyed “success” often enough for people to remember the wins; they linger in history but also endure as memorable because the blue machinists commemorated and celebrated their victories with trophies, pins, and Albany Club banquets. They made themselves legendary in their own time.

This dinner at the Albany Club, although a black-tie affair, seems casual by normal standards, with no head table and an interactive setup. The Club, founded in 1882 by John A. Macdonald and other Tories, functioned as unofficial head office of the Conservative Party ever since. The blue machine effectively took over the Club for a quarter century, helping to institutionalize its campaign operations.

The causes of its success were twofold: blue machinists pioneered new dimensions to political campaigns that gave them a competitive advantage over others, and they made their impact for decades because they were semi-institutionalized through the Albany Club and the Camp agency and PC Party offices, which gave the advantages of experience, corporate memory, and longevity as an organization.

For instance, this political faction took effective control of the Tory Party’s longest-running base of operation, the Albany Club, during the quarter-century of its most effective performance, using the prestigious facility for meetings, events, recruitment, bonding, and control. The Tory institution, founded in 1882 by the same man who formed the party itself, stipulated as a condition of membership, “No person shall become a Member of the Club unless a Conservative,” with the party’s well-being further embedded in rules both written and unwritten.

The Albany Club held sway over Tory politics in John A. Macdonald’s home province, the most reliable place over the years for producing provincial Tory governments, sending the bulwark of Conservative MPs to Ottawa, and funding party operations across the country. Supporting the national party’s budget was possible because Toronto was home to head offices of companies operating nationwide, and Tory collectors, invariably members of the Albany Club, raised cash locally for the federal party.

Yet even at the Albany Club in Toronto, the blue machinists were never more than a very strong faction; others who were not its initiated insiders continued to have roles at 91 King Street, too, intermittently serving as president, routinely booking the club’s rooms and facilities, all of them, blue machinists or not, Conservatives.

As for the blue machine’s other two bases of operation, in the Progressive Conservative Party it could never be more than a very small fraction, while at the Camp-Atkins advertising agency with its extensive political operations, it had exclusive control.

———

The cumulative record of numerous campaign innovations that history rightly credits to the blue machine transformed elections, and by extension, the conduct of public affairs, because this faction wielded power where it mattered, when it mattered, and not for just a single election but continuously over many years.

Although the blue machine’s impressive operational bases gave it more influence and endurance than other factions that intermittently appear in political parties, its operations were fundementally different from the machine politics of New York Democrats at Tammany Hall, or the Union Nationale power brokers in Quebec operating from the UN’s own private Rennaisance clubs in Quebec City and Montreal and influencing voters through its own French-language tabloid daily newspaper, Montréal-Matin.

As a human enterprise, the “machine” made mistakes. Its assiduously fostered reputation for success helped camouflage screw-ups, false starts, and errors in judgment, but could not prevent them. Mistakes are inevitable, and the Dirty Dozen even created their own version of Jerry Bruno’s “Grand Clong” award, presented to advancemen who committed a monumental campaign blunder.

Gaffes and hillarious stories live on in legend, exchanged and embellished even today at gatherings of blue machine veterans, reassuring proof that, despite the psychological benefit of the blue machine’s reputation, its renown was often just a shield from scrutiny, and that behind it were individuals trying their level best, yet not immune from human error, in the tumultous course of intense election campaigns when hundreds of jostling characters and events interact in chaotic harmony.