Chapter 47

Final Passages

Dalton Camp came of age in an era where boys modelled themselves on heroes found in books and on movie screens, characters who, through creative editing, were more luminous than anyone could ever be in real life.

Forced by his father’s death to return from the United States, one of the teen’s disappointments was to find Canada a land without heroes. “In the United States,” he recalled with longing, “we had new ones all the time, men like Charles Lindberg.” Winston Churchill became a lifelong hero to Dalton, but in Canada nobody came close to his exceptional attributes. Over time, disappointment blunted Camp’s impulse to look for greatness in others. He began to delight in exposing with wry humour, in the fine tradition of Stephen Leacock, the foibles of all-too-human political leaders with whom he’d become intimately familiar. As time passed, however, the critiques grew harsher, his humour more acidic.

When pollster Allan Gregg first met Camp in the 1970s, he thought him “a bitter old man” who “complained about everything.” Gregg also discerned how Camp “thought he should have been prime minister. I think he believed that the Progressive Conservative Party missed a great opportunity and that he’d taken a bullet for the party.”

Camp wrote brilliantly, but his speeches were delivered by others. He plotted masterful campaigns, but his strategies got other men elected to high office. He toiled in backrooms while shallower men took centre stage. Dalton aspired to be prime minister but watched as first Joe Clark and then Brian Mulroney, both of whom earlier worked for him organizing campaigns and political events, bypassed him and took up residency at 24 Sussex. All the while, many others he’d drawn into politics got elected to Parliament, something he’d twice attempted but never pulled off. A discouraged Dalton Camp looked on, not with pride, but chagrin. He had not become the hero he’d envisaged himself to be.

It is a punishment living in other men’s shadows when ambitious to make something memorably worthwhile of one’s own life. As PC Party president, Camp endured bitter and blighting recriminations for seeking, in all the ways he knew, to preserve Progressive Conservative unity when it was being splintered by John Diefenbaker’s erstwhile supporters and ardent adversaries.

On the morning of November 15, 1966, pacing together outside Ottawa’s Château Laurier Hotel at the start of a day on which Canadian political history was about to be made, Roy McMurtry voiced concern that Dalton Camp’s campaign for leadership accountability in the Progressive Conservative Party, in face of former prime minister John Diefenbaker’s adamant refusal to step aside, would likely end Dalton’s own ambitions to eventually become prime minister.

“When we’re talking about the founding party of our country,” replied Camp evenly, gazing out over the strong wide flow of the Ottawa River, “the fate of one man’s political future is just not that important.”

What McMurtry feared would be the fate of a man he admired, Camp seemed prepared to fatalistically accept, perhaps even with a nod to Nemesis for his own role in creating the personality cult around Diefenbaker, a flawed hero, in the first place.

Yet “taking one for the party” over Dief demanded personal self-effacement to a degree he could not have imagined in 1966. Dalton had been forced to exist as a hidden persona, working for leaders like Duff Roblin and Bob Stanfield who’d only meet him in clandestine ways. He was, as his brother-in-law Norman complained, “kept under wraps” by Bill Davis. He was stung by the venom of Diefenbaker loyalists, something that did not dissipate but instead grew more poisonous as time passed and legends grew. In the 1980s, when Brian Mulroney asked Camp to work for him in Ottawa as a special adviser, he tucked him obscurely into the Privy Council Office, on hand if needed but out of the way, claiming that hiring Camp was his means “to purge him of the stain of ‘disloyalty’ unfairly placed on him by the Diefenbaker diehards.”

Dalton was a prized political mistress to men publicly wedded to their lofty positions, self-protective of good appearances, noble upholders the PC Party’s sanctity. They “kept” him with government business accounts for his advertising agency and fees paid for speeches he wrote but they never credited to him, even in the permissive era of openly acknowledged speech-writers.

Part of what made Dalton toxic was how his critics nursed and spread smouldering hatreds over his role in the Diefenbaker battles. Another part stemmed from resentment among Tories over how wealth was flowing to Dalton and Norman through the Camp agency’s advertising contracts from PC governments. Even friendly PC backroom insiders like Nova Scotia’s Fred Dickson mentioned that. Mulroney, himself a direct beneficiary of blue machine support, also gave gratuitous vent to this disdain. After the 1984 landslide win, “the largest advertising contract the federal government issued was awarded to Norman through Camp and Associates,” he said, without adding that he himself approved it.

That was Brian, playing the game while taking shots at it. He described with condescension how Camp went to provinces where elections were underway, ensconced himself in the largest suite of the best hotel, wrote superb speech modules for the PC campaigners, then after the successful election outcome, collected the grateful government’s advertising account and moved his caravan on to the next campaign, until ultimately “selling his business for a handsome multiple.”

———

By 1979, when Camp published his brilliant yet bleak book Points of Departure, he’d synthesized the dual personality which circumstances had forced upon him.

That year he put into print what he’d already improvised in practice as a personal survival mechanism for quite some time. He’d coped by transferring identity to an alter ego he named “the Varlet.” In English, the term varlet can apply to a medieval page preparing to be a squire, or “a menial, low fellow, a rascal.” His identity was this second one: the rapscallion.

In Camp’s mind, his transposition into the Varlet as a separate objectified identity suited him. As this other person, he was able to write in the third person, a participant who was simultaneously a detached observer. Yet even Dalton’s self-saving re-emergence through the Varlet was, he lamented, only “passing solace to an ego consigned to the shadows of anonymity.”

Over his years in party politics, explained Camp, his “transference of so much private thought, blood, and nervous sweat to prime ministers, premiers, and aspiring opposition leaders” had yielded “only tangential gratifications, such as the applause of unseen audiences, distant editorial approbation, or an oblique electoral triumph.”

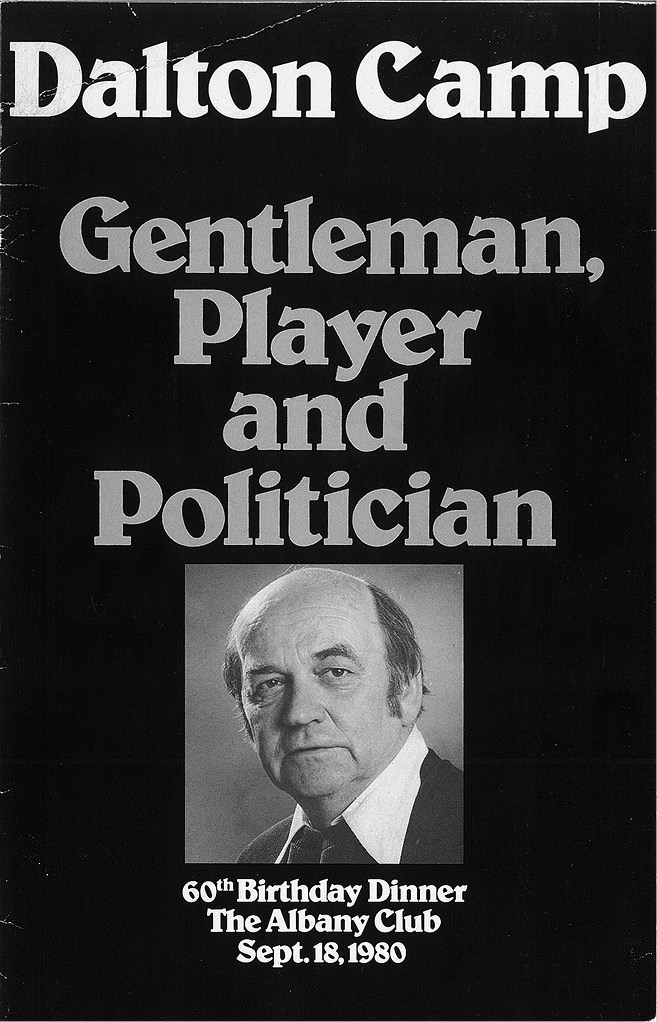

His forlorn quest to ascend to neutral political ground, combined with his enduring drive to engage others through his exceptional talent as a writer, propelled Dalton to obtain journalist credentials and join the media tours accompanying party leaders Pierre Trudeau and Joe Clark during the 1979 federal election, ostensibly an informed insider who was yet detached and dispassionate. It was a brave step, and bold, attempting to recast himself as independent analyst covering a general election campaign. His resulting book’s apt title suggested its author was himself heading in unknown directions. The brilliance of his political analysis, combined with insights, candour, and artistry, make Points of Departure as searing and exceptional as his 1970 memoir, Gentlemen, Players & Politicians, which covered Dalton’s initial involvement in New Brunswick politics from 1948 up to successful completion of the first Diefenbaker campaign in 1957.

But by 1979, as told in Points of Departure, a different aspect accompanied everything Dalton observed. Camp’s personal estrangement from politics soured his view of election campaigning, even though many practices he witnessed followed patterns he himself had first devised. His end-of-the-Seventies account was a three-part mixture: observant campaign coverage, flashbacks to people and events forming background to the election, and personal angst.

The paradox was that he could not leave politics alone, even though his growing cynicism about it was destroying him personally and casting an obscurant shadow over his lifelong accomplishments. Tortured by his uncertain identity, Dalton by this date was weary of playing backroom organizer and éminence grise, “a career given over to conceptualizing political strategies and reducing them to more or less precise expression” for the benefit of other players in the spotlight of Canadian politics.

The more his personal quest for a role in national leadership eluded him, the greater his turmoil. The more intense this distemper became, the harsher grew his scrutiny of others. Believed to be the Tory Party’s saviour by some, a traitor by others, Camp now aspired only to ascend high enough to “give all alike the benediction of his cool.”

He’d travelled far: organizing for George Drew, helping smash entrenched Maritime Liberal machines, being John Diefenbaker’s loyal campaign manager, making creative efforts as national PC president to support The Chief during his tenure in office, forcing a leadership review when it became his destiny to do so, and becoming the single most divisive man in the party’s entire history. At that point, Camp said, “he began to enter back doors, ride service elevators, and occupy hotel rooms pre-registered under assumed names” and endure “the dark nights of a prolonged penance.”

It was a Faustian bargain Dalton had contracted: trading excursions into public life for incursions into his most inner self.

———

Beneath Dalton’s tortured contradictions, though, was an enduring, staggering talent, which occasionally broke out like a ray of sun through a storm cloud.

The title of Camp’s 1970 political memoir, Gentlemen, Players and Politicians, seemed apt for Dalton, his singular self. Norman Atkins, with his creative team at the Agency and blue machinists, fashioned Dalton’s Albany Club birthday banquet in 1980.

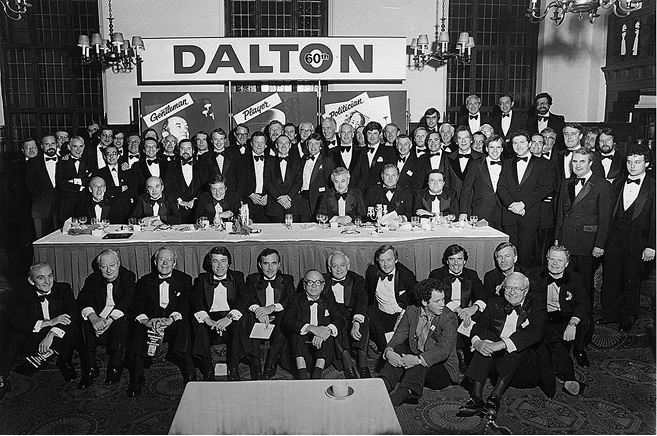

On September 18, 1980, Dalton Camp’s friends hosted a black-tie dinner at the Albany Club to celebrate his 60th birthday. The six seated at the table, l-r, are Robert Stanfield, Dalton Camp, Roy McMurtry, Nate Nurgitz, Norman Atkins, Hugh Segal. The sixty others present included Tory players, elected politicians, party office holders, the Spades, pollsters, journalists, and future party leaders.

On September 18, 1980, when the same Allan Gregg who’d found Dalton a “bitter old man” attended Camp’s sixtieth-birthday celebration at the Albany Club, he was “blown away,” saying, as he listened to the guest of honour, “I could not believe anybody could be so smart.” He was glimpsing a version of Dalton once again himself, enjoying a happy moment in a familiar setting with true friends. Gregg, thinking I am in the presence of greatness, henceforth placed Camp and Pierre Trudeau in the same rank as “towering intellectuals.”

Here, for a shining moment, was the old Dalton, the articulate Canadian who’d inspired others to not quit the PCs but stay; to not vote Liberal again but join with him in a higher quest; dozens of talented individuals from across Canada to form a campaign-ready battalion and follow him.

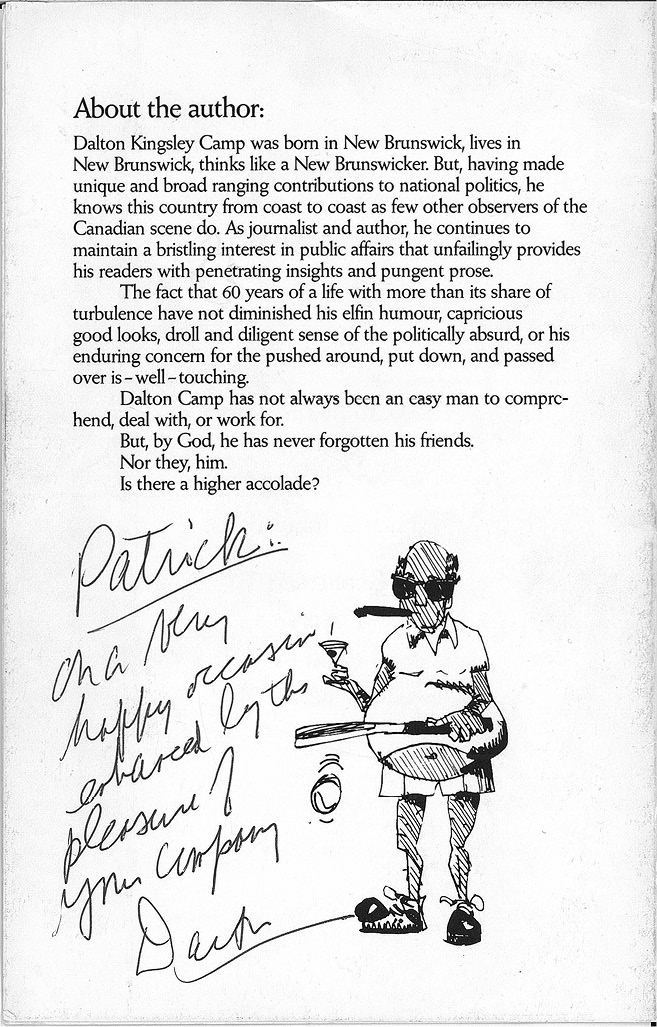

A synopsis of Dalton’s qualities appeared, along with the Rough-In logo, on the back of the printed birthday keepsake. The happy celebrant inscribed the author’s program.

Even so, the surfacing of the Varlet betrayed Camp’s deeper reality. He’d intermittently experienced bouts of depression, calling them visits from his “black dog,” using Winston Churchill’s own term for his dark days of despondency. Struggling to reconcile how his life’s bargain, like Faust’s, had transformed him, Dalton seemed to come unmoored and drift.

He not only reinvented himself as an anti-hero for his book, but, in his new guise the Varlet left his long-cherished wife Linda and married Wendy Smallian, a comrade from an election campaign bunker and seen by some close friends of the Camps as resembling an earlier version of Linda herself. Dalton built a new home on an elaborate scale, isolated in rural New Brunswick. He spent his considerable proceeds from sale of his half-interest in the agency until the money was gone.

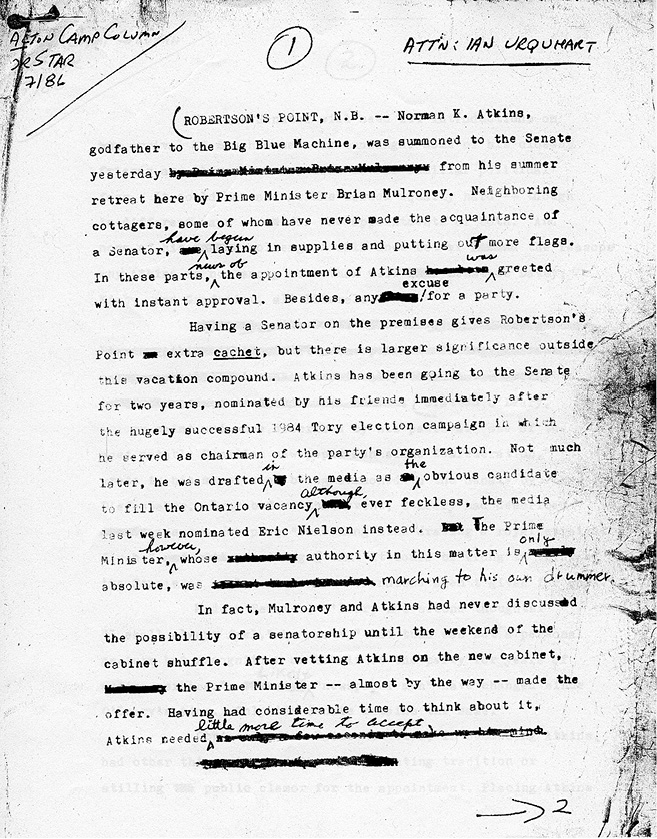

He did not get appointed to the Senate, his brother-in-law did, which provoked him to write a column he had to edit before sending it for publication. In 1986, he accepted as consolation prize a position in the Privy Council Office at Ottawa, a move so improbable and inappropriate that few could comprehend Prime Minister Mulroney offering it or Camp accepting it. Before long, Dalton bitterly regretted the mistake, one more in a lengthening parade of them.

Dalton sat in his New Brunswick writing shed, itself at a remove even from his isolated house, pounding out columns for Canada’s largest English-language daily, the Toronto Star, a Liberal newspaper that persisted, over his repeated objections, in ending his pieces with a tag line that reminded readers the columnist had once been president of the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada. Whether the publisher hoped to indicate the Star was tolerant, or Camp had recanted, was never clear.

In 1986, when, influenced by Bill Davis’s intervention, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney appointed Norman Atkins to the Senate, his brother-in-law sent his column to the Toronto Star expressing mixed views. Written on his trusty portable typewriter at Robertson’s Point and corrected by hand, Dalton did his best to bring humour to the milestone in Norman’s life, as he again saw someone junior to him advance further.

Things became still more confusing when Camp, trying to recast his political identity, began identifying himself as a “Red Tory.” The concept had become so detached from the meaning University of Toronto political scientist Gad Horowitz originally intended, when coining that term in 1965 to explain how it was that Tories and socialists shared communitarian values, that it lost all salience at ground level in Canadian politics. Dalton contributed to this confusion by arguing in public that one’s stance on capital punishment determined whether or not one was a Red Tory.

From a studio in Fredericton, Camp charmed national radio audiences on Peter Gzowski’s CBC network program, Morningside, dissecting the week’s political events with New Democrat Stephen Lewis and Liberal Eric Kierans. They engaged with intelligent partisanship, civility, and humour. It was Camp at his mature best, talking about politics the way he always had, with others whom he respected for their informed opinions and clear thinking.

These national CBC commentaries, Toronto Star newspaper columns, and the books he assembled to place previously published opinion pieces in the hands of a wider readership, all benefitted from the Varlet’s detachment from public affairs. Yet, simultaneously, they perversely chronicled a growing detachment from the very Tory partisanship that Dalton Camp had thrived on, and, indeed, done so much to incubate, for decades.

A collection of his late 1970s and early 1980s offerings, published under the weird title An Eclectic Eel, gave a further glimpse of how Dalton now saw himself. The Varlet had become an eel. Using an “anonymous” quote, he said his role was to be, “Like eels at the bottom of the fish barrel, who keep them all awake up there.”

A compilation of columns for a 1995 book entitled Whose Country Is This Anyway? testified to Camp’s emergence as a scourge of the New Right, big corporations, and predatory Americans. His “clear-minded, witty, and hard-hitting” views on Canada’s so-called neo-conservatives were applauded from the political left by June Callwood, Rick Salutin, and Linda McQuaig. At this point, concluded John Pepall, a Toronto lawyer and Conservative writer, “Camp was simply beyond caring.”

———

There was, however, much that others could care about in Dalton Camp’s life. Wherever he’d landed, Dalton could always convey, better than commentators or reporters who’d never experienced politics from the inside, candid realism about public life, including its bleaker and ironic backstage dimensions.

For enduring public good, that same realism infused five volumes of recommendations from the Camp Commission on Ontario’s Legislature. Implemented by the Davis government, the landmark changes in Ontario election finances and legislature operations remain a constructive and enduring part of Dalton’s legacy, and, by extension, Bill Davis’s as well. It was pioneering legislation in North America, transforming elections and the parties who contest them, a fitting marker for a man who’d created and sponsored many other innovations that had also altered forever the conduct of Canadian politics.

Within the Progressive Conservative Party, to which he’d devoted the best of his best years, another of Camp’s legacies was the breakthrough amendment to the constitution requiring “leadership review” to ensure a democratic party itself enshrines the principle of democratic accountability.

There was much to lament, too.

The Varlet had tried to restructure his difficult personal narrative by spinning it from a different perspective, reaching back into medieval times for his identity as a low rascal. Yet had he reached even further into antiquity, a more telling image could have been found. For there was, by its end, the unmistakable quality to Dalton Camp’s life of a Greek tragedy.

———

Norman Atkins looked for heroes even more.

From their first meeting at Robertson’s Point in 1942, observers could see “he worshipped Dalton like a hero.” When Norman’s father died, the man who’d become his friend in boyhood years, then his brother-in-law, next his “older brother and friend,” even became something of a surrogate father. “Hero” was far too weak a word to describe Norman’s view of Dalton.

As Dalton withdrew into himself and other pursuits, away from the advertising agency and the PC Party, Norman found a new friend who became a political hero to him, Bill Davis. He celebrated Ontario’s premier as “the epitome of a great leader” and relished his close relationship with “Billy.”

“Norman wanted a similar relationship with Brian Mulroney to the one he enjoyed with Bill Davis,” explained his friend Paul Curley, “but it wasn’t on. Mulroney was just not that kind of guy.” As a result, an estrangement between Atkins and Mulroney began, because Norman did not accept that the closeness he had with Ontario’s premier wasn’t going to be possible with Canada’s prime minister. His injured feelings worked themselves out in very human ways. Norman had “not taken credit for the wins in Ontario,” noted Tom Kierans, “the way he tried to claim it Ottawa.”

Atkins had seemed astute, at that first caucus meeting on Parliament Hill in September 1984, to direct attention away from his political backroom organization and on to Brian Mulroney, not just because the new PM was a public figure and the party’s champion of the hour, but because political parties ripple with spreading circles of resentment. Staying in the background was safer. Atkins’s long-time friend and PC backroom colleague in Nova Scotia, Fred Dickson, said that Norman was “extremely modest, in fact, too modest.” That self-effacing quality had enabled him, in his best years, to master the party’s backrooms by fusing effective teams of disparate individuals, many of whom had very large egos.

Yet, not getting sincere credit from Mulroney, even in private, created a downward spiral in their feelings about one another. The less Brian acknowledged his value, the more Norman claimed it. John Laschinger, as a blue machinist, always warned his colleagues, “Be careful not to take too much credit if you’re an organizer.” He quoted Atkins’s aphorism, “Organizations don’t win elections, they lose them,” only to then add, “Norman forgot that sometimes you win because of the candidate, not the organization.” Laschinger put it in a nutshell: “Norman thought he’d won the campaign for Mulroney and made him prime minister. Brian resented that.”

Thinking he might shore up faltering relations with the big blue machine by naming Dalton Camp to the Senate, the PM received an intervention from Bill Davis to the effect that Norman Atkins had done far more for him than Dalton, and that, with Norman’s much closer control over the campaign apparatus, he’d serve Mulroney better in the upper house, the way party organizers always do, being able to work full time on the party’s next campaign at public expense. Meanwhile, Mila Mulroney and Norman had a lengthy lunch at the National Arts Centre, with the main entrée a senatorship. The PM named Atkins to the Senate in 1986, saying about the appointment in a cutting way that getting into the Senate “had been Atkins’s best campaign of all.”

Brian Mulroney was happy to benefit from what the blue machine could deliver, yet remained jealous of any credit it got. He said, “I asked Norman Atkins to be the national campaign chairman for the simple reason that I wanted Davis personally onside in the election.”

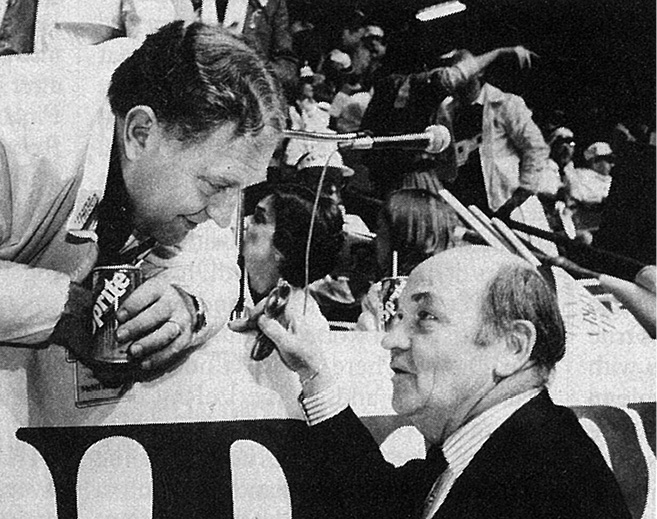

While the prime minister greets guests, Norman Atkins whispers to Mila Mulroney in the entranceway of their official residence. Most political events have many versions, depending on who is describing them, and Norman’s acquisition of a seat in the Senate was no exception.

He recounted how, when telling Ontario’s premier how pleased he was that members of the big blue machine were playing a major role in his federal campaign, Davis clarified the relationship in the somewhat self-serving way one political leader might when speaking to another in confidence. “Brian, the big blue machine is the best at getting the buses to meet your plane, taking you to a room overflowing with supporters.… But the leadership, strategy, and message for the campaign, that’s what I do. The real big blue machine? You’re looking at it right now.” — meaning himself.

In other contexts, not filtered through Brian Mulroney’s effort to denigrate Atkins for thinking he had a role winning a campaign that he’d chaired, Bill Davis was never that dismissive of the Camp-Atkins political formation’s role in helping him win elections, nor so forgetful of its role in the Park Plaza Group he himself had instituted to do far more than address bus scheduling and airplane logistics.

———

Following his death in March 2002, Dalton’s remains were laid to rest deep in New Brunswick’s heartland at the Lower Jemseg cemetery of St. James Anglican Church, a final resting place of locals since the 1850s, just 150 kilometres from where he’d been born eighty-one years before.

———

Upon becoming a senator, Atkins moved his trophy-laden office to Ottawa. Departing the agency, Norman sold Camp & Associates to a group of senior employees who wanted and got 100 percent of the business, not just his half-interest, so that their efforts could be fully rewarded.

Further changes followed at the agency. Hugh Segal had joined as an equal shareholder to develop the public relations and government lobbying side of the business, but when he, too, left for Ottawa, in 1992, to become chief of staff to Prime Minister Mulroney, the principals bought Hugh’s interest. “We then,” said Dianne Axmith, made Paul Curley “an offer he couldn’t refuse,” enabling him to expand his public relations business as an affiliated operation, which he did by getting successful Tom MacMillan and others to join him. Axmith herself had risen from Atkins’s initially reluctant assistant to president of the agency. With Atkins and Segal departed for parliamentary precincts, the principals renamed the firm “Axmith, McIntyre, Wicht.” After Axmith and Wicht retired, John McIntyre, who, as husband of his daughter Gail, had the strongest enduring link to Dalton, renamed the firm Agency 59 to commemorate the year 1959 when his father-in-law first launched his advertising business.

Atkins’s departure from the agency coincided with another major change in his life: the end of his marriage. He had spent so many years travelling and working long hours on campaigns that he and Anna Ruth had grown apart. In Ottawa, after a time spent living with another senator, his friend Finlay MacDonald, he found a new partner in Mary LeBlanc.

Norman encountered a difficult time, too, with his political relationships. The Progressive Conservative Party in which he been a major player all his life had agreed to merge with a successor entity of the Reform Party, the Canadian Alliance, a culmination of Preston Manning’s failed experiment. The goal was to present a unified conservative front and prevent further easy Liberal romps to majority government facilitated by vote splitting. Over 90 percent of constituency-elected PC delegates to a national convention voted to ratify the merger.

Norman was uneasy, knowing how Dalton in his final years had railed against the “right wing” in Canadian politics. Yet Bill Davis, to whom Norman had become closer as Dalton grew more distant, helped engineer the merger, at the request of his party’s leader, Peter MacKay, and had negotiated its terms. It made more sense, Davis understood, to be together than apart. If one favoured moderate or progressive policies, the best way to achieve them was to stay involved, advance them as a player on the field, and get back into office to implement them. It also was an example of Davis being “loyal to the leader,” chided the former premier gently, a principle Norman professed.

Across the decades Norman Atkins and Dalton Camp shared political goals in Tory campaign backrooms and leadership conventions. Here they exchange views between front-row seat and convention floor. Their resilient partnership enabled the brothers-in-law to direct and transform Canadian campaigns between the 1950s and 1980s.

In the seductive comfort of the Senate, however, Lowell Murray, with whom Norman had been closely acquainted for years, pointed out that it made no difference to their generous salaries if they “held out on principle” and continued to sit as self-styled “Progressive Conservative” senators. In Canada’s unaccountable legislature, a senator’s affiliation can be whatever he or she designates, even the name of a legally defunct political party. Norman and Lowell huddled in isolation with other holdouts like Joe Clark and Sinclair Stevens, also in denial that another necessary turn had been taken in the Tory Party’s long and winding road for survival, failing to embrace engagement as a better strategy than separation.

As a result of his partisan identity crisis, Norman worked out a series of questions for his Senate assistant Christine Corrigan to pose in interviews with some fifty blue machinists, ostensibly for a book about his career as a campaign organizer. Included were questions concerning their views about Norman’s appointment to the Senate and his remaining a “Progressive Conservative” after the merger — Norman’s own variant on deep polling research. How much easier if, as for so many years, he’d just been able to follow Dalton’s reassuring lead on this sort of thing.

———

When Norman died, at age seventy-two in September 2010, his fellow Tory senator and former business partner at the Camp agency Hugh Segal authoritatively pronounced, “He was, and will forever be, father emeritus of the big blue machine.” By that standard, Dalton Camp would be in perpetuity the operation’s “grand-father emeritus.”

“Dalton Camp’s determination to live a life of ideas and a life full of action,” Norman himself had acknowledged in his final Senate speech the year before, “was an inspiration to me.” Indeed, it had been, from the very first day his brother-in-law and mentor brought Norman into the fray with him. Atkins’s career began with Camp’s efforts, not to build a political machine, but bust one, their first cause to unseat an entrenched Liberal regime — “the corrupt McNair machine” as Camp called New Brunswick’s power juggernaut in his 1949 radio broadcast — and replace it with a Progressive Conservative government. Norman was a junior helper, absorbing Camp-style politics throughout his formative years.

Atkins, in turn and by extension, became instrumental in redesigning election campaigns for more than half a century. His pioneering use of extensive organization charts and campaign timetables on headquarters’ walls matched the campaign blueprint in his mind, because he wanted to be certain everyone on his diverse teams understood the structure and implemented his plan. His insistence on budget control as a management tool introduced a new campaign orderliness to a field not previously known for businesslike practices. His early adaptation in Canada of the latest American polling techniques reoriented how election strategies and campaign advertising were shaped.

Norman’s legacy in revamping election advertising also took fresh directions with the formation of an in-house consortium agency of top specialists from different firms, K-Tel messaging for political penetration through television, and more aggressive attack ads. His early support for direct-mail fundraising techniques adapted from the Republicans in the United States helped PC Canada Fund build a lucrative mailing list of sixty-five thousand donors which, when coupled with a super computer, put the Tories in the green and made Grits green with envy. He transformed campaigns by introducing autocratic central control, imposing an identical party brand across all ridings and uniform messaging in all election materials, an exclusive emphasis on the leader through the focus of commercials, and making the leader’s tour a media-friendly campaign centrepiece. A born and bred American, Norman saw Canadian elections rather like U.S. presidential campaigns.

The same camaraderie he’d enjoyed at Appleby, Acadia, and in the army he fostered as a bonding agent in his campaign teams through the Rough-Ins, the Spades, the Albany Club, and every Tory campaign backroom he occupied. Probably no one convened more breakfast campaign meetings than Norman Atkins. In time, he took a lead to include women in his male dominated enclaves, including the Rough-In and Albany Club, and promoted their careers, though he remained most at ease in the company of other men. He knitted it all together, uniquely, using his competitive advantage of supply-chain management skills honed in the exacting environment of the United States Army quartermaster corps, an exceptional training ground for a Canadian campaign organizer.

Norman did not accomplish any of these things alone. He always worked in close harmony with others. But whatever he did, Norman saw the way forward by following Dalton’s light.

Looking back today at the dramas and conflicts that defined the big blue machine’s campaigns, or how this partisan entity redirected the nature of Canadian politics, or even at Norman’s non-partisan campaigns for Juvenile Diabetes and Acadia University, it is clear why Atkins told his fellow senators, in his final speech, “Life is all about showing up and truly involving oneself in one’s community.”

He showed up, involved himself, and accomplished results that impacted Canadian political history. His accomplishments came by recruiting and coordinating the willing, and allowing each to perform to their maximum, so long as each played according to his musical score and under his director’s baton.

Norman followed Dalton but he was not Dalton. He did not use big words. He was self-effacing. As a speechmaker, he was a nervous journeyman, but in the craft of political campaigning, he was an undisputed master who let his deeds speak for themselves. Sometimes, they had to.

“When Norman died,” noted Tom Kierans, “Mulroney’s quote was ‘he made the trains run on time.’ That was it. Atkins was a master technician, but Brian would never acknowledge than anybody but he had anything to do with his victories. He understood politics, more than anyone else, in his view. In Ontario, Davis would give much greater credit to those who fashioned victories.”

When he died, it could not have surprised anyone who’d known him that Norman Atkins’s remains would be buried in Lower Jemseg alongside the grave of his political mentor, business partner, brother-in-law, and best friend.

“Dalton and Norman were one with each other again,” said Atkins’s resilient wife, Anna Ruth. “They did everything together, complemented one another’s skills and, in the end, lie buried side by side in New Brunswick.”

Their companion tombstones nestle serene beside Lower Jemseg’s stone church, atop a small hill near the flowing Saint John River, in a province both men cherished as home.

Norman would follow Dalton anywhere.