The future Marilyn Manson was born in 1969 and christened Brian Warner. It was to be a pivotal year in American history, the year hippie culture reached its zenith at the Woodstock festival in New York State. Harvard psychology professor-turned LSD guru Timothy Leary later wrote, in his essay on ‘The Woodstock Generation’, that ‘the “Woodstock experience” became the role model for the counterculture of that time. The Summer of Love kids went on to permanently change American culture with principles that the Soviets in 1989 called glasnost and perestroika. Hippies started the ecology movement. They combated racism. They liberated sexual stereotypes, encouraged change, individual pride and self-confidence.’ He went on to compare Woodstock to the rites of the Ancient Greek god of wine, Dionysus, describing the festival as ‘the greatest pagan, Dionysian rock’n’roll musical event ever performed, with plenty of joyous nudity, and wall-to-wall psychedelic sacraments. And click on this: not one act of recorded violence!’

Twenty-five years on, the Woodstock festival was revived – but with little for the ‘Summer of Love’ children to groove to. Young rock fans had replaced the peace sign with the devil’s horns signal, and most agreed the show had been stolen by a band named Nine Inch Nails promoting the album Pretty Hate Machine. The original festival had resulted in upstate New York being declared an official disaster area – the naïveté or incompetence of the hippies resulting in disastrously inadequate facilities. The thirtieth anniversary festival, in 1999, had to be stormed by riot police. Timothy Leary had overlooked the fact that the wild revels of Dionysus he evoked involved not only sex and intoxication, but also violence: twelve tractor-trailers were destroyed, speaker towers toppled and concession stands looted, as festival-goers danced through fires that rapidly burnt out of control. And click on this: more than half-a-dozen rapes reported!

Marilyn Manson had been scheduled to play the 1999 Woodstock Festival, but declined when a suitable time-slot could not be found. As the British music paper NME observed: ‘Fact: while the original Woodstock Festival – high-watermark of the sixties idealism of peace, love and good music – was taking place in 1969, Marilyn’s namesake Charles was preparing for his dune buggy attack battalions to put an end to the hippy dream in a blood soaked orgy of slaughter in the Hollywood Hills. Perhaps the irony was not lost on the organisers of Woodstock ’99.’

WINDOWS ON THE SOUL

Perhaps the most striking illustration of the marriage of opposites in Marilyn Manson are his mismatched eyes. This is a pervasive theme: in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell he says that both his childhood pet, a dog named Aleusha, and the cat belonging to his girlfriend Missi had naturally mismatched eyes; David Bowie, an important early inspiration, has one discoloured eye due to a fight at school; in the 1976 Antichrist horror-fantasy The Omen (which scared little Brian Warner as a child), when Evil drives the Holy Spirit from a possessed priest it is said to escape through one of his eyes, changing its colour.

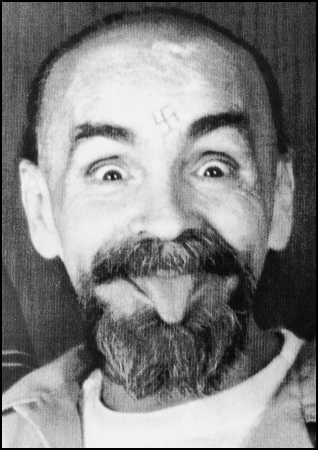

Many of those who attributed hypnotic, or even magical, powers to Charles Manson also believed they were contained within his penetrating stare. On a contemporary level, coloured contact lenses are a fashionable form of body-modification – albeit a subtler, less visceral version than the tattooing or piercing normally associated with the modern primitive cult.

When articulating the concept behind Marilyn Manson on MTV, its frontman explained, ‘I was writing a lot of lyrics five or six years ago, and the name Marilyn Manson I thought really describes everything that I had to say. You know, male and female, beauty and ugliness, and it was just very American. It was a statement on the American culture, the power that we give to icons like Marilyn Monroe and Charles Manson and since that’s where it’s always gone from there. It’s about the paradox. Diametrically opposed archetypes.’

All of Marilyn Manson’s early members followed the same formula for choosing stage names, adopting the christian name of a female sex symbol or starlet and the surname of a notorious male murderer. Marilyn Manson, however, was always destined to be the most memorable, marrying two icons at opposite extremes of twentieth century culture. Marilyn Monroe is a screen legend whose immense popularity and potent sexual magnetism, frozen in time forever by her untimely death in 1962, have turned her into the most powerful contemporary goddess of love and lust. Public revulsion at the crimes of Charles Manson, convicted of ordering his hippie ‘Family’ to conduct a series of atrocities in 1969, have made him into an icon of incomparable intensity, a devil figure symbolising hatred and death.

‘I watch a lot of talk shows,’ the 1990s Marilyn later observed, ‘and I was struck by how they lumped together Hollywood starlets with serial killers, just bringing everything to the same sensational level. But Monroe had a dark side with her drugs and depression, and Manson had a true message and charisma for his followers, so it’s not all black and white.’

Manson felt compelled to clarify his position when defending himself against accusations that his own work had inspired an act of mass murder in 1999: ‘The name Marilyn Manson has never celebrated the sad fact that America puts killers on the cover of Time magazine,’ he wrote, ‘giving them as much notoriety as our favourite media stars. From Jesse James to Charles Manson, the media, since their inception, have turned criminals into folk heroes.’ But whither the thin line between ironic comment and celebration?

SEX KITTENS WITH CLAWS

In his autobiography, musing on the origins of his moniker, Marilyn Manson laments that ‘people always ask me about the darker half of my name but never about Marilyn Monroe’. To be fair, neither Monroe’s singing, nor the dialogue from her films, ever surface regularly in Marilyn Manson material the way that quotes from Charlie Manson do. Her importance is as an icon, a symbol of beauty and lust, though – as the contemporary Marilyn is quick to point out – this Hollywood legend also has a darker aspect. This is evident in her largely light-hearted acting career: The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and Niagara (1955) belong in the gritty noir genre, while her popular comedy Some Like it Hot (1958) is a cross-dressing farce played out against the grim background of the St. Valentine’s Day massacre.

Marilyn Monroe – Hollywood’s tragic love goddess – with friend.

As a girl who achieved the American dream of rags-to-riches, but lived a largely miserable life, there’s something faintly unsavoury about Monroe’s onscreen persona. She was a sex symbol who – unlike more upfront or sophisticated Hollywood vamps – cloaked her sexuality in a feigned childishness which, at times, suggested an almost paedophilic appeal. Before her Hollywood break she worked on the fringes of the pornography trade, famously posing nude for a calendar. Later, after becoming successful, she became addicted to drugs.

Anton LaVey, Marilyn Manson’s spiritual godfather, claimed to have had an affair with the pre-stardom Monroe, at the very beginning of the 1950s. In his biography, The Secret Life of a Satanist, author Blanche Barton observes that, ‘In 1973 LaVey wrote in a Cloven Hoof article that Marilyn Monroe will become the satanic “Madonna” of the 21st century. In a sense that’s already happened. Since her death, she has been fashioned into a goddess . . . Marilyn Monroe is not a goddess pure and sexless, but satanically just the opposite – a fleshy goddess: passionate, flawed, enticing, beautiful.’

As with Marilyn Manson himself, other band members’ names have been a hybrid of female sex symbol and all-American mass murderer. Bassist Twiggy Ramirez took the first half of his name from a famous London fashion model of the Swinging Sixties, a short-haired, flat-chested waif who took androgyny into the mainstream. Guitarist Daisy Berkowitz paid tribute to Daisy Duke from Seventies TV series The Dukes of Hazzard – in this cheesily subversive show, where the heroes were white trash (normally portrayed as villains or comic relief) who regularly fooled the corrupt local cops and Daisy an adolescent male fantasy in provocatively-brief denim shorts. Original keyboardist Zsa Zsa Speck opted for Zsa Zsa Gabor as a role model – a former Miss Hungary and actress in such uncelebrated crap as Queen of Outer Space and Frankenstein’s Great Aunt Tillie. The epitome of the celebrity who is famous simply for being famous, Zsa Zsa is still considered part of Hollywood’s tacky aristocracy.

Current keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy adopted the first part of his moniker from the pop star – Ms. Ciccone – rather than the Holy Mother of God. Madonna, like Marilyn Manson, has encountered much criticism from Christian lobbyists, and was denounced as blasphemous by the Vatican for her smoulderingly-erotic ‘Like a Prayer’ video. When relations between Marilyn Manson and Trent Reznor’s Nothing Records became shaky, there was even talk of Madonna signing the band to her Maverick label. This fell apart, however, when the peroxide-blonde pop siren allegedly insisted Madonna Wayne Gacy stop using ‘her’ name – the delicious irony being the suggestion that the provocative Italian-American singer, apparently indifferent to the offence her stage name gave Roman Catholics, was herself offended by this personal ‘blasphemy’ against her.

Other starlet namesakes are, perhaps, less obvious. Drummer Ginger Fish owes his first name to Ginger Rogers, the perky Hollywood actress whose overblown song and dance epics partnering Fred Astaire during the 1930s made her a household name. Bassist Gidget Gein took his name from Gidget, the air-headed heroine of a series of unspeakably feeble teen-beach-party movies of the late 1950s and early 1960s. The original Gidget was played by Sandra Dee, described by one critic as ‘one of the least interesting teen idols in cinema history’, whose only mark on cultural history is a song in the 1978 nostalgic hit Hollywood musical Grease (‘Look At Me, I’m Sandra Dee’).

KING OF THE CREEPY CRAWLERS

On 9 August 1969, police found the bodies of beautiful, heavily-pregnant film star Sharon Tate and four of her friends at her exclusive Beverly Hills mansion. They had been brutally stabbed, bludgeoned and shot, their blood used to daub the walls with the legends ‘WAR’ and ‘PIG’. The following night, a Los Angeles couple named Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were stabbed to death at their suburban home. This time the dripping crimson graffiti read ‘DEATH TO PIGS’, ‘RISE’ and ‘HEALTER SKELTER’ (sic), while ‘WAR’ had been carved into Leno’s stomach. When the perpetrators were caught, to the horror of both ‘straight’ society and the counterculture, they turned out to be members of a hippie commune calling itself ‘the Family’.

Eight members of the Family were found guilty of connected charges, with four sentenced to death (later commuted to life imprisonment) in a controversial courtroom drama that at times resembled a medieval witch trial. Among those receiving the ultimate penalty was a short, bearded ex-con named Charles Manson, who, while not present at the murders, was still found guilty of conspiring in the crimes by virtue of being the Family’s nominal leader. To this day his supporters maintain Charlie never killed anyone, while less sympathetic commentators have linked him to as many as 35 unsolved murders. The truth, not least concerning what motivated the horrific Tate-LaBianca massacres, is now swathed in a thick cloak of mind games, drug abuse and modern myth which is devilishly difficult, perhaps impossible, to penetrate.

Charlie Manson was born the illegitimate son of a promiscuous wild child named Kathleen Maddox in 1934. By age twelve, the state had put him into the ‘care’ of a brutal Catholic boys’ home, from whence he graduated, via a life of petty crime, to a series of reform schools and gaols. Despite the appalling abusiveness of these institutions, by the time of his parole in 1967 the jailhouse was Charlie’s entire world (‘My mother’, as he would later claim) and he begged not to be released.

The world Charles Manson found outside was in the grip of the psychedelic revolution. When he drifted to its epicentre on the USA’s West Coast, the hippies’ free love and drugs blew his mind. But Charlie’s mind games, and the survival skills developed in gaol, proved just as mind-blowing to the semi-nomadic ‘Family’ that assembled around him – not least the young girls who became the unlikely guru’s harem. Cleverly, perhaps brilliantly, manipulative, Charlie was also indelibly scarred by his dysfunctional upbringing. Somehow, in August 1969, the cocktail of drugs, frustration and youth rebellion combined with the ex-con’s mind-control complex to send the Family spinning into the helter-skelter vortex of violence that shocked the world.

The first song on Marilyn Manson’s debut album has the opening line ‘I am the god of fuck’ – a direct quote from Charlie Manson, later appropriated as a title by his new androgynous namesake. Just as some early concerts were peppered with readings from Dr Seuss, others featured quotes from Charles Manson; early promotional material was also littered with references and graphics easily identified with Charlie by the counter-cultural cognoscenti. Marilyn fought hard to keep the song ‘My Monkey’ – based on the Charles Manson song ‘Mechanical Man’ – on Portrait of An American Family, despite the deep reservations of his record label.

Brian Warner discovered Charlie’s music back in high school, buying the killer’s notorious Lie album. Later, he would integrate Charlie’s lyrics into the poems that finally evolved into Marilyn Manson songs. He recalls first becoming intrigued by the notorious criminal via the song ‘Mechanical Man’, describing its creator as ‘a gifted philosopher, more powerful intellectually than those who condemned him. But at the same time, his intelligence (perhaps even more so than the actions he had others carry out for him) made him seem eccentric and crazy, because extremes – whether good or bad – don’t fit into society’s definition of normality. Though “Mechanical Man” was a nursery rhyme on the surface, it also worked as a metaphor for Aids, the latest manifestation of man’s age-old habit of destroying himself with his own ignorance, be it of science, sex or drugs.’

‘A gifted philosopher’? Isn’t Marilyn Manson – just like the mainstream media he seems to despise – recreating his criminal namesake as a folk hero? Is the criticism of the Reverend Charles ‘Tex’ Watson – formerly of the Manson Family, now a born-again Christian – that Marilyn Manson is bringing ‘the Manson madness into the hearts and minds of millions’, valid? If it is, then he is only one of a long tradition of counter-cultural figures who have fallen under the spell of Charles Manson.

At the same time Woodstock ’99 was descending into chaos, fashionable photographer Geoffrey Cordner was preparing an exhibition entitled These Children That Come At You With Knives for a Hollywood gallery, consisting of a series of staged photos re-enacting the Manson massacres. The roll call of models included members of such hip bands as the MC5, Porno for Pyros, Tool and the New York Dolls. Guns ’n’ Roses recorded one of Charlie’s compositions, ‘Look At Your Game, Girl’, on their album The Spaghetti Incident? – much to Marilyn Manson’s displeasure, as he claimed Axl Rose had stolen his idea of recording a Charles Manson song. (It wasn’t only Manson’s wrath that the band incurred – Manson victim Sharon Tate’s sister Patty was outraged, leading Guns ’n’ Roses to give up any profits from the recording.) There is talk of an animated feature based on Charlie’s life and crimes, featuring the voices of bands like White Zombie, L7, the Ramones and Rancid, while – in perhaps the ultimate white-trash tribute – Charlie Manson has already starred in an episode of cartoon show South Park.

KILLER TUNES

Discussing Charlie Manson’s influence on Marilyn Manson, his namesake explained, ‘I think Charles Manson is the greatest rock star of all time. He was all about music. He never even had to have a hit and he’s one of the biggest stars that you could ever find. That’s something that we can thank America for, whether you like it or not, America put him there.’

Whatever roles Charlie Manson, the mirror man, adopted for those around him, as far as he himself was concerned all he wanted was to be a successful musician. Taught to play guitar in gaol by gangster Alvin ‘Creepy’ Karpis (former member of the Ma Barker gang and one-time Public Enemy Number One), on his release Charlie used his influence on the hippie scene to try to launch a musical career – even cutting a demo album with members of the Family. (One theory concerning the Tate killings was that the intended target was a record producer, Doris Day’s son Terry Melcher, who Charlie believed had discarded him).

Charlie cultivated a friendship with Dennis Wilson, the reckless drummer of sunny surf sensations the Beach Boys. For a while, Manson’s Family even lived in Wilson’s luxury log cabin on Pacific Palisades, while the Beach Boys recorded one of Charlie’s compositions – ‘Cease To Exist’, suitably sanitised for public consumption as ‘Never Learn Not To Love’. But relations with the Family soured, and Charlie’s crew was evicted. Charlie responded by sending Wilson a silver bullet, the threat inspiring the Beach Boy to sleep with a gun under his pillow. Meanwhile, Charlie was becoming increasingly fascinated by the Beatles’ White Album, reading secret messages and odd prophecies into its lyrics. According to some commentators, it was these ‘messages’ which inspired him to order the 1969 massacres.

The notoriety those crimes attracted finally inspired the underground release of Charlie’s demo album, under the title Lie (its sleeve a mock-up of the Life magazine cover story on the Manson crimes). Over the years, this would be followed by a sporadic series of bootleg releases smuggled out of gaol for a growing cult audience. Charlie’s music has been memorably described by Jim Goad as ‘an incredibly depressing sonic mix of Hank Williams and the Velvet Underground’ – despite this, it continues to attract acclaim from the dark extremes of the musical avant-garde, such as satanic folk-rocker Wendy Van Dusen, of Neither\Neither World, who cites him as a primary influence. Body-building punk poet Henry Rollins spoke about trying to officially release an album of Manson’s music during the Eighties, observing, ‘He’s this five feet four inch guy, sitting behind bars, and he terrifies people.’

While Axl and company could plead that they were looking at the Manson myth from an ironic perspective, others on the dark fringes of the counterculture had been more than happy to get their hands bloody. When news originally broke of the arrest of a Californian commune for the horrific Tate-LaBianca murders in 1969, many hippies assumed it was a frame-up orchestrated by the notoriously corrupt LA police. When it became apparent, however, that these unlikely butchers were almost certainly guilty, much of that support melted away, as the Love Generation began to wonder what had happened to their dream. In the words of writer David Dalton (a hippie who initially believed the Manson Family to be innocent), Charlie had killed ‘part of ourselves, our Edenic others who had once believed we could create a new heaven and a new earth’. However, a hard core of radicals in the hippie movement continued to hail him as a martyr to their cause, lauding his atrocities as revolutionary acts. Hippie terrorists the Weathermen declared 1969 ‘The Year of the Fork’ in Charlie’s honour (one of the victims died with a fork stuck in his belly), and told fellow revolutionaries to ‘dig it’.

Charles Manson - the hypnotic hate messiah who heralded the end of the Summer of Love.

Perhaps the most controversial celebration of the Manson murders came from the opposite end of the political spectrum to the long-haired leftists of the Sixties. The 8/8/88 Rally was held in a San Francisco theatre on 8 August 1988 (the anniversary of the Tate slayings), featuring a rare exploitation film based on the Tate massacre entitled The Other Side of Madness, sinister avant-garde music and apocalyptic right-wing speeches. Among those leading the proceedings were occult fascist and respected experimental musician Boyd Rice and Zeena LaVey, youngest daughter of the notorious Anton LaVey. Both were prominent members of her father’s Church of Satan, an organisation Marilyn Manson was later initiated into with the clerical rank of Reverend.

The reasons given for ‘celebrating’ the murders are instructive. Firstly, the organisers felt that the Family’s 1969 murder spree had killed off the Sixties, ending the Summer of Love in a bloodbath. Nikolas Schreck (a fellow right-wing occultist and partner of Zeena LaVey) explained, ‘The Sharon Tate murder was a symbolic representation of the end of an entire way of thought, of compassion for the weak, peace for its own sake, pacifism that breeds stagnation. That entire way of thinking was destroyed on August 8th 1969 and that is why we chose this evening to perform a ritual of cleansing and of purification.’

Considering the hippie movement portrayed itself as a movement of peace and understanding, there has been a surprisingly long line of suspects keen to hold up their hands to the murder of the Love Generation. Iggy Pop, asked what contribution he and his wild proto-punk band the Stooges had made to the Sixties, replied that they ‘wiped them out’. Alice Cooper, regarded by some as Marilyn Manson’s prototype, is fond of boasting he ‘single-handedly drove the stake through the heart of the love generation!’ Johnny Rotten, noxious vocalist with punk legends the Sex Pistols, made great play of his raw hatred of hippies. While promoting Antichrist Superstar, Marilyn Manson would compare the album with the impact the Manson massacre had on the Summer of Love. ‘I think it is [having that effect], and will continue to do that. The media and politicians really made Charles Manson the scapegoat for a whole generation, and I see that tag being placed on me. And it’s a tag I’ve almost accepted with Antichrist Superstar.’

Many of the celebrants at the 8/8/88 Rally shared his belief that Charles Manson is ‘a gifted philosopher’. But just what is his ‘philosophy’? The few members of the Family that remain faithful to their stubby messiah describe it as ‘ATWA’: Air, Trees, Water, Animals. At one level this is just radical environmentalism, given a sinister edge by its implicit assumption that man is worth no more, and often less, than the creatures around him.

Some radical right-wingers see Charlie as a kind of racist mystic – notably James N. Mason, ejected from the American Nazi Party for his belief that Manson was the spiritual successor to Adolf Hitler. This aspect of Manson’s ‘philosophy’ relates to the theory known as ‘Helter Skelter’: cobbled together from aspects of racism, biblical prophecy and Beatles lyrics, it predicted black militants would overrun the white Establishment, but would in turn be conquered by another enlightened power in the form of Charlie and his ‘dune buggy attack battalion’. Certainly, Charlie has used racist language that is at odds with the hippie ethos, and famously carved a swastika into his forehead during trial – an affectation soon adopted by his ‘disciples’. Apologists point out, however, that Charlie’s racist rhetoric is what you might expect from someone brought up in the jailhouse, where progressive ideas about racial harmony are a rare luxury, and that the swastika is not just a Nazi insignia but an ancient Hindu religious symbol (with the symbol being reversed).

The most compelling aspect of Charlie Manson’s philosophy is the idea of himself as a ‘mirror man’ – a theme that recurs frequently in Marilyn Manson’s work, notably in his allusions to ‘the Reflecting God’. At a metaphysical level, Charlie suggests that you deliberately abandon, or even destroy, your own ego in order to get closer to truth or reality. On a more concrete level it describes the source of Charlie’s power – his chameleon-like ability to suppress his own ego in order to become what those around him want him to be, whether a Satanist, a hippie, or a Nazi. There are echoes of the mirror man in the singer’s description of why he first adopted the Marilyn Manson persona, describing it as ‘the perfect story protagonist for a frustrated writer like myself.’ The character of Marilyn was designed to be a disdainful misanthrope, a spiteful celebrity who charms his way into the world’s affections, but then ‘once he wins their confidence, he uses it to destroy them’.

In the words of David Dalton, who nearly fell under Charlie’s spell in 1969, ‘When you read Manson’s words or hear his rants you cannot help but be struck by their obvious truth. Many things he says are not only absolutely right they are profound observations on our culture. And as long as we remain a hypocritical selfish society they will continue to be telling criticisms. The disorientating thing about Manson’s vision is that his train of thought follows a form of Möbius logic where every insight turns in on itself with vicious introspection. He’d be really dangerous if he weren’t plagued by his own warped mental aberrations.’

Less philosophically, the real reason why Charlie Manson is such an icon for so many of the marginalised and disaffected in today’s society is his status as ‘king of serial killers’. It’s an ironic achievement: Charlie is only known to have directly committed one murder, and might not even be guilty of that. Both his criminal conviction and his notoriety rest on the charge that he masterminded the series of killings he sent his ‘Family’ to perpetrate. In his defence, Charlie compared his own situation to that of President Nixon sending young American recruits out to die in Vietnam.

Ultimately, the reason Charlie Manson’s name continues to feature prominently in serial killer studies is more to do with the media and entertainment world than with criminology. The media reinvents serial killers as mythical monsters, giving them titles more suited to American Gladiators or Marvel superheroes than murderous inadequates. Winning him a good deal more fame than the standard fifteen minutes, Charles Manson’s status as a serial killer has more to do with his ‘star quality’ than any particular aspect of his crimes.

Ironically, in a culture obsessed with fame, the condemnatory attention lavished on these murderous misfits may actually encourage them – serial killers enjoy their stardom. As criminology expert Paul A. Woods commented to me, ‘No matter how well these guys have covered their tracks over the years, they need to stake a claim on some squalid little footnote in history. Like John Wayne Gacy, who pleaded innocence most of the way up until his execution, all the while selling his kitschy clown paintings to people who regarded him as “the killer clown”.’

And like all stars, serial killers have their public. From the respectable retired colonels who join societies dedicated to Jack the Ripper, to the young rock chicks who bombarded Richard ‘the Night Stalker’ Ramirez with marriage proposals and nude polaroids of themselves, we have developed a twisted, sadomasochistic relationship with our twentieth-century monsters. According to Woods, ‘Because these people dig up the blackest impulses from the basement of the human condition, they’re expected to be evil geniuses. Hannibal Lecter is an amoral anti-hero – kind of Dracula meets Milton’s Lucifer – because we find it difficult to accept some nerdish clerk, or insignificant oddjob man, granting himself a god-like power over life and death.’

HIPPIE HALLOWEEN

Nothing could have cemented the conceptual relationship between Marilyn Manson and Charlie Manson as powerfully as the location for recording the band’s debut album – 10050 Cielo Drive, where the Tate massacre took place. The circumstances gave the album’s title, Portrait of an American Family, just the right sinister overtones. Marilyn himself was able to fulfil his ambition to enter the murder site after producer Trent Reznor rented the former Polanski-Tate house, equipping it as a studio to record Nine Inch Nails’ classic The Downward Spiral.

Many Nine Inch Nails fans speculated that those songs from the album dealing with murder were inspired by the Manson slaughter. Reznor was adamant this was not the case. ‘I had the song “Piggy” written long before it was ever known that I would be in that house,’ he pleaded. ‘ “March of the Pigs” has nothing to do with the Tate murders or anything like that. When I rented the place I didn’t even realise it was that house. When I found out I thought it was kind of interesting. I didn’t think “Oh, it’ll be spooky to tell people that . . .” I don’t idolise Charles Manson, and I don’t condone murdering people because you’re a fucked-up hippie trying to make a statement. But it’s an interesting little chapter in American history that it was cool to be a part of.’

The atmosphere soon began to take its toll. ‘The first night was terrifying,’ Reznor confessed. ‘By then, I knew all about the place; I’d read all the books about the Manson murders. So I walked in the place at night and everything was dark, and I was like, “Holy Jesus that’s where it happened.” Scary. I jumped a mile at every sound – even if it was an owl. I woke up in the middle of the night and there was a coyote looking in the window at me. I thought, “I’m not gonna make it.”’

‘If you thought about what happened there, it was disturbing late at night,’ conceded Marilyn Manson, ‘but it wasn’t exactly a haunted house. No rattling chains or anything, but it did bring across some darkness on the record.’ Inevitably, perhaps, a few odd manifestations interrupted the recording of both Portrait of an American Family and The Downward Spiral. According to Manson, during the recording of the song ‘Wrapped in Plastic’ a sample of Charles Manson saying, ‘Why are the kids doin’ what they’re doin’, why did the child reach out and kill his mom and dad?’ kept erupting inexplicably onto the tapes.

‘But after about a month I realised that if there’s any vibe up there at all, it’s one of sadness,’ said Reznor. ‘It’s not like spooky ghosts fucking with you or anything – although we did have a million electrical disturbances. Things that shouldn’t have happened did happen. Eventually we’d just joke about it: “Oh, Sharon must be here. The fucking tape machine just shut down.”’

BLOOD AND CELLULOID

The serial killer first became a cultural icon via the cinema. In Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic Psycho, the ‘hero’ was Norman Bates: a nice, polite young man who just happens to kill people at the behest of his dead mother. After Norman, the serial killer was ready to replace the vampire and the werewolf as the kingpin of celluloid terror.

The ‘stalk and slash’ flicks that started in the 1970s – notably Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) – were an increasingly formulaic sub-genre of the horror movie, plotless showcases for gore effects. Teenage victims were chased interminably by an unstoppable masked killer, who finally dispatched them in a number of improbably colourful ways. The critics hated them but the most successful spawned countless sequels, their primarily young, male audiences lapping up these shamelessly cheesy bloodfests.

As the fictional serial killers in these films became ‘heroes’, merchandisers jumped in to make a buck out of their youthful fans. The monster-in-human-form became a rebellious icon for thousands of teenagers.

Director Oliver Stone satirised this trend in his savage 1994 film Natural Born Killers. Visually overwhelming and curiously cartoonish, many critics accused it of glorifying what it purported to attack. The accusations intensified when some linked the film – which professed to be a statement against violence – with shootings in the US and France. One Texan youth who decapitated a young girl is even claimed to have said he ‘wanted to be famous like the Natural Born Killers’.

Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails was the natural (born) choice to co-ordinate the soundtrack, a selection of searing noise and twisted rock’n’roll classics that became a best-seller. (Marilyn Manson were due to contribute their cover of ‘rock’n’roll Nigger’, but Stone opted for the Patti Smith original – though the Manson track ‘Cyclops’ remains on the soundtrack, if not the soundtrack album.)

The most successful serial killer movie to date is The Silence of the Lambs (1991), some considerable distance removed from the stalk-and-slash genre. In some ways, however, it’s even more morally dubious than its poverty-stricken predecessors. The maniacs in stalk-and-slash flicks were mostly inarticulate behemoths, hormonal teen frustration personified – serial killer Hannibal Lecter, on the other hand, is a charming, cultured man, a kind of cannibalistic James Bond. If Halloween’s Michael Myers is a crude, sadistic wish-fulfilment fantasy for powerless male adolescents, then Lecter plays the same role for mainstream Middle America. His fictional transformation into immoral superman was complete in the novel Hannibal in which Lecter not only becomes the hero, but where he even gets the girl.

Or, as Marilyn Manson observes, ‘I look on the serial killers cynically, more tongue-in-cheek. It’s basically everybody’s fear of death that fascinates them with serial killers. America makes them into heroes. America complains that kids are idolising them, but they don’t have anyone to play with.’ In a typically ironic comment, he alludes to the parents who leave their children to be brought up by the TV. And, with the media’s fascination with violence and murder, that virtual baby-sitter becomes the child’s first introduction to the throwaway culture that breeds serial killers.

Shocking as it may be to some, Marilyn’s ‘tongue-in-cheek’ exploration of murderous celebrity is restrained compared to the serial killer trading cards and T-shirts, even serial killer fan clubs, that proliferated in America during the 1990s. Before we join Governor Keating of Oklahoma in lamenting the decline of western civilisation, let’s consider the disturbingly articulate – and deeply cynical – opinion of the aptly-named Jim Goad, editor/publisher of ANSWER Me!, a magazine of self-professed ‘Hate Literature’. In his feature ‘Night of a Hundred Mass-Murdering Serial-Killing Stars’, Goad gushes that ‘Killers are exterminating angels, some of the sweetest souls who ever lived. They are the beautiful people.’ If this sounds familiar, note that the article ran in 1992 – four years prior to the release of Antichrist Superstar. ‘Murder is less of a threat than cigarette smoking, arterial plaque, industrial toxins, or driving a car. Yet people shy away from murder as if there’s something wrong with it . . . Oblivious to fanciful moralistic constructs, they [killers] have the guts to take matters into their own hands. Are they disturbed? Perhaps, but that’s a word we consider synonymous with “visionary”. Some would say we’ve stepped over the line and are glorifying them. Of course we are.’

As ever, Goad leaves the reader gasping for breath from the sheer audacity of his assault. He may not be typical of his generation, but Jim Goad represents the furthest extreme of a social current that’s been building since the 1960s, a culture of productive hate. Similarly, when Brian Warner invoked Charles Manson, he was invoking a god of hate, just as Marilyn Monroe is the twentieth century’s goddess of love (or lust). ‘You cannot sedate all the things you hate’ is scrawled across Marilyn Manson’s debut album, referring to the efforts of our politically-correct culture to legislate the language of hate out of existence.

‘They implore you to fight the hate,’ writes Jim Goad in The Redneck Manifesto, his attack on politically-correct America. ‘They want you to kill it, squash it, suffocate it, exterminate it. Blind as bats, they entirely miss the point that the problem isn’t hate . . .

It’s a natural emotion, not some sinister aberration . . . Hate is as useful as love, and it often works a hell of a lot quicker. Hatespeak is usually more honest than lovespeak, and it’s always better than doublespeak . . . How can you protest your oppression (perceived or actual) and sound lovey dovey about it?’

Antichrist Superstar opens with ‘The Irresponsible Hate Anthem’, faithful Spooky Kids soon taking up its chant of ‘We hate love! We love hate!’ Asked to justify this, Marilyn explained: ‘I don’t think people express their hatred enough. They need to let that out. Political correctness has really suppressed hatred. Which in a sense is good. I’ve got no problem with that. I don’t want everyone going around killing each other. That’s not my message. But there’s no reason to be ashamed to express a natural human feeling, which is hatred. You need balance . . . The word “hate” gets misused a lot, too. People don’t appreciate its value.’

Perhaps this is what he’s talking about when he compares the impact of Antichrist Superstar to that of Charlie Manson’s crimes three decades before. Whether it comes from the counterculture – like the hippie Woodstock of 1969 – or from the mainstream – like the corporate Woodstock of 1999 – it pays to be suspicious of anyone trying to sell the doctrine of universal love. The Christian Church sold itself as a creed of universal love, but the actual result was a thousand years of brutality, stagnation and repression. Charlie may not be the philosopher that his misanthropic disciples claim – any more than he’s the satanic monster portrayed by the mainstream media – but when he slew the Summer of Love he may well have been doing the world a favour.

‘Charles Manson was saying a lot of things that are not unlike what I’m saying today,’ observed Marilyn Manson. ‘There’s a lot of irony in the way things have come into play, there’s an irony in the fact that 25 years ago there was the same kind of tensions socially, racially. There was the same threat of war, there was Woodstock, there was a lot of hypocrisy with the hippie culture and their seed of love bullshit. Hippie, short for hypocrite, of course. A lot of people don’t want to look into what he had to say, because of what he did, but I think it’s important to point out that what he did is really no different than what my father did in Vietnam – my father killed people, he didn’t believe in it. Charles Manson killed people, he at least believed in it – that he had a reason for it. Neither one is right or wrong, it just is. Killing is killing, there’s no difference. Society makes one person a hero and another person a criminal, it’s just a popularity contest. Morality is decided by the man with the most artillery.’

When he became more familiar with fame, Marilyn would revise his view on his notorious namesake, observing in 2000 that he previously hadn’t been sure ‘who was good and who was bad’. With typical eccentricity, Marilyn maintained he had confused Charles Manson with Doors vocalist Jim Morrison. For the modern Marilyn Manson, Charles Manson was reduced to an emblem of how modern America is just as enchanted with inadequate sociopaths as it is with talented artists. Celebrity and notoriety had become interchangable.