When asked to name his influences, Marilyn Manson responded with a typical mixture of the profound and the banal: ‘I’m into philosophers like Nietzsche, Freud, Darwin, Crowley, LaVey and Roald Dahl, Dr. Seuss, even the King James Bible.’

Indeed, Reverend Manson of the Church of Satan has expressed his admiration for The Bible on more than one occasion, explaining, ‘I like it as a book. Just like I like The Cat In The Hat.’ In comparing Christianity’s holy book with a children’s fantasy, a brilliant and influential scientist like Charles Darwin with a kids’ author, there’s serious intent beneath his provocation. To take us down into the sinister childhood underworld he evokes, we have to be guided by another of the ‘philosophers’ Marilyn cites – the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

FUN AND FEAR

Marilyn Manson is a veteran practical joker, subjecting support bands to his black sense of humour. In the band’s early days local amenities were popular targets, particularly those frequented by kids, like toy stores and amusement parks.

One elaborate prank, executed at Christmas, is remembered in some detail in his autobiography. Marilyn cruised the neighbourhood in his girlfriend’s car, robbing roadside nativity scenes of their Jesus and black wise man figurines. The plan was to cause a local panic with a ransome note, purportedly from a black militant group, declaring,“We feel that America has falsely illuminated and plasticized the wisdom of the black man with its racist propaganda about his so-called ‘white Christmas’.”’

There are faint echoes, in this harmless Yuletide prank, of the Tate-LeBianca murders – after which, it was suggested that the grotesque graffiti daubed on the walls by the Manson Family were designed to implicate black militants.

HEAD SHRINK

Sigmund Freud was a Jewish physician, born in the Czech Republic (then Moravia) in 1856, whose ideas revolutionised the way we perceive ourselves. The father of psychoanalysis, Freud’s theories are no longer well respected in the scientific community, and you’re more likely to find Freudians in the English literature department of a university than its psychology faculty. Nevertheless, he was a pioneer in understanding the human mind. Freud introduced the concept of the ‘unconscious’, suggesting we are not aware of much of what’s going on in our heads, and that many of our mental problems are tangled up in hidden mental processes. Furthermore, he claimed many of our profounder problems are traceable to repressed childhood traumas, and, controversially, that sex preoccupies us to a level which we are unwilling to admit. To access the unconscious, Freud used dream interpretation, symbols, hypnosis and freeform conversations with his patients.

Freud’s ideas were far from universally popular. He challenged the idea of childhood innocence, suggesting that we are sexual creatures all the way throughout our development. Even more heretically, his research suggested the ultimate conclusion that religion was nothing more than a mental condition, or even an illness. Since his death from cancer in 1939, his theories have come under increasing attack from those who challenge the scientific validity of his research, and accuse him of substituting inventiveness for logic. Digging around in someone’s unconscious can do more harm than good to their mental welfare, and blame for the current plague of counsellors, therapists and other quasi-medical witch-doctors can be laid at Freud’s door. His theories have also been controversially misused in recent years by mental health professionals who implant ‘recovered memories’ in their patients, which they then claim as evidence of childhood abuse. The idea that traumatic memories could be repressed since childhood and later recovered was, of course, instrumental in creating the recent ‘satanic child abuse’ myth.

If everyone were to write a ‘confessional’ as full and frank as The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, then the world’s Freudian analysts would be out of work in a week (no bad thing). One of Freud’s most influential ideas was that all of our adult neuroses can be traced back to childhood traumas, often of a sexual nature. He claimed we often repress these painful episodes, and made a living out of unearthing them from paying customers. Marilyn Manson does such a good job of digging up his own childhood traumas, it almost seems that he’s doctored them so that he makes a little more sense in a Freudian light.

The Long Hard Road Out of Hell opens with a young Brian Warner visiting his grandfather Jack’s house in the company of his cousin Chad. The old man’s private den is a shrine to perverse, deviant sexuality – a dank place full of ancient condoms, grotesque erotica and repulsive sex aids. In an interview conducted prior to his book, Marilyn located in this experience the reason why his songs featured so many strange childhood motifs.

‘When I was twelve,’ he explained, ‘I got my first exposure to sex because I had a real weird grandfather who had a lot of strange pornography in his basement. You know, I started going through it and I found it, and it was a lot of weird stuff – you know with animals, and you know, stuff that you wouldn’t really expect to find in your grandfather’s house. And that’s how I got introduced to everything, and it gave me a strange outlook.’ Significantly, Jack Warner, who his grandson paints in a far from sympathetic light, has his den in the cellar – a location associated with dark, primal desire by many Freudian psychologists. The old man even uses the sound of his model railway to conceal his perverse activities, trains and tunnels being among the most overt Freudian symbols for sex.

In true Freudian style, Marilyn sees sexual significance in many of the apparently innocent elements of his ‘very strange childhood’. Speaking of his favourite cartoon shows he recollects, with typical bawdy irreverence, ‘I think I first got an erection watching Scooby Doo. I had something for Daphne.’ Early Marilyn Manson promo literature also featured outrageous doodles of favourite children’s characters, such as Scooby Doo, with ‘LSD’ written over his hallucinogen-addled eyes, and the Cat in the Hat, pornographically enjoying himself with penis in hand. (Placing characters from cartoons and popular juvenile fiction in very ‘adult positions’ has always been popular in the counterculture – most recently with the pop artist Frank Kozik’s posters and record sleeves for bands like punk funsters the Offspring.)

Other important Marilyn Manson motifs are prefigured back in the schoolyard, if not the kindergarten. When the Christian Heritage School he attended banned candy, so little Brian Warner harnessed the lure of the forbidden and became ‘a candy pusher’. As he observes in his autobiography, ‘I gravitated toward candies that were the most like drugs. Most of them weren’t just sweets, they also produced a chemical reaction. They would fizz in your mouth or turn your teeth black.’ As an adult he would also confess, ‘I’m addicted to sugar I guess. Caramello bars because they are so thick and sugary. They almost make you sick just to eat them.’ (Sara Lee Lucas, the one original band member who didn’t derive his stage-name from a screen star, took the first half of his name from Sara Lee, the popular American cake manufacturer – merging cynically with Henry Lee Lucas, the white trash killer.)

Just as it sexualises cartoon characters, early Marilyn Manson promo art juxtaposes lollipops and candy canes with hypodermic syringes. The relationship between the candy of childhood and the forbidden ‘candy’ of drugs pervades our consumer culture: legitimate drug companies are constantly admonished for making their pills look colourful and exciting, in case they are mistaken for sweets by curious young children. The child’s lust for candy is evocative of the infantile craving adult junkies have for their ‘candy’ of choice. Just as drug addicts drift into crime to feed their habits, so many children’s first brush with the law results from shoplifting candy at their local store. Like drugs, excessive candy consumption is considered wicked and has numerous health implications.

And, as Marilyn suggests, candy can have effects similar to those caused by drugs: from the short-lived energy rush that comes with excess sugar, through hyperactivity resulting from bright food colourings, to more extreme claims of behavioural effects. (Few are more extreme than the case of ‘the Twinky defence’, where a civic official named Dan White successfully claimed that his large intake of sweet junk food and soda had affected his judgement, leading to his murder of a colleague and the San Francisco mayor in 1978.) Needless to say, candy features prominently in Marilyn Manson lyrics as a symbol of temptation – such as ‘Sweet Tooth’, from Portrait of an American Family, where a craving for sweets is used as a metaphor for an unhealthy relationship.

Another branch of the Marilyn Manson aesthetic sprang from the seed of religion planted early on in childhood. In a letter written by Charlie Manson to President Ronald Reagan in 1986, he warned, ‘Keep projecting what not to do and you make the thought in their brains of what can and will be done.’There are few better examples of this reverse psychology than the young Brian Warner’s attraction to music condemned as ‘satanic’ by his Christian teachers, acclaimed by him as an ‘unflappable source of album recommendations’. Such sanctimonious condemnation would later provide the fuel for launching the exuberantly blasphemous Marilyn Manson.

Few symbols of young Brian’s growing disenchantment with Christianity are as memorably symbolic – even Freudian – as his early experiences on the stage. Cast as Jesus in a school play at the age of six, the impressionable little thespian had his improvised loincloth ripped away, exposing him, literally, to the scorn of his peers. In one fell swoop, the Christian messiah was revealed to him as human, probably all too human. Perversely, this embarrassing episode prefigures the child’s future as a rock star with a messianic, megalomaniac image, also known for dropping his pants on stage. (Observers of the feud between Marilyn and his erstwhile mentor, Trent Reznor, may be intrigued to know that Reznor played Judas on the school stage – though Nine Inch Nails fans may protest that the roles were reversed in adult life.)

In one way or another, all of Marilyn Manson’s records have been based on the theme of childhood – even Mechanical Animals, which on the surface is about the very adult world of Hollywood celebrity. While promoting the album, the frontman was asked if he was afraid of fame. ‘No,’ he responded, ‘but this record is about dealing with the alienation of it and how in some ways it makes you feel like an infant. You know, everything is big. When you’re a baby everybody wants to look at you and kiss you, sometimes you just have to shit in your pants. And the whole world cleans it up.’

THE PSYCHO CIRCUS

KISS erupted onto the New York rock scene in 1972 as an irredeemably tacky extreme of glam rock, but the band soon exploded out of that ghetto with bombastic energy and populist showmanship. KISS toured tirelessly with a live show featuring screaming guitars and merciless salvos of explosions cascading over the band members, resplendent in black and silver, teetering on enormous platform boots. The whole concept – complete with sinister clown make-up and fire-breathing – owed as much to the circus as it did to rock tradition, and the critics remained resolutely unimpressed. They dismissed KISS as comic-book rockers: the band responded by donating blood for the ink of a best-selling Kiss comic book.

Founder and bassist Gene Simmons summed up the band’s attitude when speaking of culture in a Rolling Stone interview: ‘I think Shakespeare is shit! Absolute shit! He may have been a genius for his time, but I can’t relate to that stuff. “Thee” and “Thou”: he sounds like a faggot. Captain America is classic because he’s more entertaining.’ Kids could relate to that, and did so in their millions, turning KISS into the biggest band in the US by the late Seventies. The KISS Army devoured countless albums, posters, dolls, and (of course) lunchboxes. The self-appointed arbiters of cool may not have approved of these crass, commercial, demonic showmen, but KISS formed the gateway to the forbidden world of rock excess for a generation of American adolescents. (As attested by Christian anti-rock campaigners, who began preaching that KISS was an acronym for ‘Kids In the Service of Satan’.)

One of those adolescents was Brian Warner, whose first record album was KISS Alive II, and whose first concert, in 1979, was a KISS gig. The boy became an ardent fan, joining the KISS Army, playing with the toy popgun that accompanied Love Gun, and decorating his room with KISS merchandise (including the fondly-remembered KISS lunchbox.)

He wasn’t on his own. ‘KISS changed my world,’ said Trent Reznor. ‘It seemed evil and scary – the embodiment of rebelliousness when you’re age twelve and starting to get hair on your balls.’ As Thurston Moore of proto-grunge legends Sonic Youth confirms: ‘Growing up in the suburbs, a few of my friends and I were heavily into KISS.’ A recent tribute album featured contributions from artists as diverse as Stevie Wonder, Faith No More, Anthrax and, of course, Nine Inch Nails. ‘When we were kids everyone thought Queen and KISS were terrible,’ said Reznor. ‘Now they’re a point of reference.’

‘I want lunch boxes and dolls,’ Marilyn Manson asserted in an early interview, revealing his cultural roots. ‘I don’t want to change our style to be accepted by the public, I want the public to change their style. I would have no problem if we became the KISS of the nineties.’

Just as Antichrist Superstar was about shedding childhood innocence and vulnerability – evolving from ‘the Wormboy’ into the monstrous, unfeeling superman – so Mechanical Animals is about reversing that process. It is, as one interviewer suggested, a quest for purity. ‘That’s indeed the case,’ its creator concurred. ‘Only I try to reach that by going in the opposite direction. The more you go through, the more you can leave behind. It may sound bizarre, but while rooting in the mud pool of life I feel myself getting cleaner bit by bit. I would like to become as pure and immaculate as a child. The boy I once was, but that got stained by life.’

‘My Monkey’ – the Charlie Manson-inspired ditty Marilyn has identified as the best track on Portrait of an American Family – has a twisted nursery-rhyme feel to it. ‘There’s points where my voice and the child’s voice mutate together,’ its creator observes, ‘and you can’t tell who’s who. I think that’s my favourite part of the record, because it’s where I really get to become a child again.’

The most overt reference to childhood on American Family never made it to the finished edition. The sleeve was to be decorated with a picture of Brian Warner as a child, photographed naked by his mother. ‘The point of putting that there was knowing that people would react and they would be offended and say “Look at this child pornography,”’ he explained. ‘But it’s not and for you to see it as child pornography proves that there’s something in your mind and that it’s not me being sick, it’s you being sick.’ However, Nothing Records saw it as needless provocation and vetoed the picture’s use.

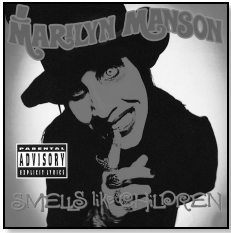

The public’s perceptions of child abuse became a central theme of the follow-up record, Smells Like Children. At heart a children’s record for adults, the EP is a bitter psychedelic requiem for innocence destroyed. Inevitably, Marilyn Manson’s less perceptive critics interpreted it as an endorsement of that very same abuse. As he observed, ‘Smells Like Children, for me, was a bit of a joke because people always assume that things I mention in songs are promoting child-molestation.’

While Freud’s work had helped to show that ‘the child is father to the man’, by the time of his death, in 1939, previously ‘seen and not heard’ children had become sacred icons of innocence. The 1970s saw the rising prominence of child sexual abuse as a social issue – a disgusting abuse of power that seems to be age-old, only recently forced out of the shadows of social taboo. This was a very ugly can of worms, with many people unwilling to recognise that the vast majority of child abuse took place between family members. During the 1980s, evangelical Christians took advantage of this to promote the myth of a secret conspiracy of Satanists who ‘ritually’ abused children in the name of the Devil. This comforting myth was not only an outrageous lie, but also darkly ironic inasmuch as the clergy have long been associated with sexual mistreatment of the young.

Nevertheless, parental anxiety – which can often reach irrational levels – combined with sensational news copy to ensure the myth thrived for a decade, until deflated by government reports and general scepticism. Ironically, real Satanists remained largely untouched by this latter day witch-hunt. The chief casualties were persecuted members of paranoid communities, wasted government resources that would have been better spent on apprehending genuine criminals, and, ultimately, the credibility of those who propagated this nonsense.

By 1995, when Smells Like Children was released, the myth had largely been discredited. However, Marilyn Manson made heavy use of satanic iconography in their promotional material, which, addressing an incendiary topic such as child abuse, still made for a boldly provocative statement. By this time, proponents of the ritual abuse myth had identified themselves as the ‘Believe the Children’ lobby. Operating on the level of emotional blackmail – they were ‘on the side of children’, which inferred that their opponents meant them harm – most of their evidence rested on fantastic testimony gleaned from children in the most dubiously unprofessional interview circumstances. The only credence came from blind faith in the idea that children never lie.

By way of contrast, the genuine satanic position on the controversy was expressed by Anton LaVey, who knew – like Roald Dahl – that children can be cruel, while at the same time deeply approving – like Dr Seuss – of their wonderful flights of fancy. LaVey liked children, referring to them as ‘natural magicians’ – magic being the art of turning the imaginary into the real, the first qualification for which is a vivid imagination. Marilyn Manson, a keen student of LaVey, observed that ‘childhood is a magical time when kids believe things, and if you believe something it will come true for you. That’s the thing, adults get so depressed, so jaded because everything is so horrible, that they stop believing in dreams and they don’t try and live them out.’

As with his belief in the power of childhood fantasy, so with his love of children’s entertainment. ‘I’ve found fantasy television shows to be a great escape. The imagination is something that should be appreciated. That’s why I think children are innately magic, because they realise the power of their minds and haven’t been de-purified by television.’

The most obvious reference to childhood fears, childhood fantasy and children’s entertainment on Smells Like Children was the sleeve photo depicting Marilyn Manson resembling the Child Catcher – the villain from the 1968 film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (also alluded to in the EP’s ‘Shitty Chicken Gang Bang’). Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was based on the children’s book about a flying car by Ian Fleming, author of the James Bond novels, and was adapted for the screen by Manson favourite Roald Dahl. The Child Catcher is a sinister, repellent creature who lures children using sweets, and can track his quarry by smell (hence the title of the Manson EP) – the distillation of the fears of child and parent alike, the predatory stranger who abducts children for unspeakable purposes. (On ‘Organ Grinder’, which uses samples from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Marilyn takes on a persona that is half Child Catcher-half Charlie Manson.)

Robert Helpmann as the Child Catcher, the authentically creepy villain of Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

Channelling the Child Catcher for the cover of 1995’s Smells Like Children.

As Manson explained, ‘the Child Catcher in that story Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was one of the things that influenced the title of that, because he was a guy whose job was to smell out children, and kidnap them and lock them away, but I was real scared of him when I was a kid. But when I got older, a lot of people told me I look like him. So it kind of, I guess, became part of my personality.’ But why identify with such a repellent character? ‘I, just like everyone else, love fear. And I especially like the phenomenon of villains in children’s movies, and what makes kids scared of them.’

The outrage deliberately generated by Marilyn Manson can, in part, be seen as a reaction to the ‘safety culture’ that is a feature of life in the 1990s. Cries for ever-greater censorship of entertainment grow ever more shrill, in the mistaken belief that removing violence or immorality from the screen will magically remove it from life. To Marilyn, it’s all a red herring compared to the darker frisson he used to receive from his beloved world of children’s entertainment: ‘I watch some stuff today, but stuff today is very watered down. As kids we used to watch some very terrifying stuff, but it was really candy-coated so it was given to us more subversively. Now it’s an R-rated movie, and if you’re a kid you get to see it that way, but you don’t get to see it in G-rated movies. It’s a weird way that things have evolved. I’m really into the old stuff. I like to scare little kids. I like little kids, I feel that I still am a little kid, so there’s a strange relationship with that’.

If The Long Hard Road Out of Hell is to be believed, it is clear that this passion for scaring children is heartfelt. Manson describes visiting Disney World with some friends while tripping on LSD, coming across two twins eating turkey dinner, who he describes as resembling the sinister alien infants from the science fiction movie Children of the Damned. The malignant, mischievous Marilyn raised his shades to reveal his mismatched eyes, grinned, then sliced his arm with a razorblade. Unsurprisingly, the two kids dropped their lunch in terror, while their tormentor walked away ‘exhilarated by my success, because there’s nothing like the feeling of knowing you’ve made a difference in someone’s life, even if that difference is a lifetime of nightmares and a fortune in therapy bills’.

It’s another memorably unsettling incident in a book cram-packed with them, seeming so cruel and pointlessly provocative that the reader wonders why the author wants to present himself in such an unattractive light. But the point becomes clearer when considering how hypersensitive the modern world is to the welfare of children, and how Marilyn once observed in an interview that, ‘The closest we’ve ever come to being arrested was having a six-year-old kid in a cage on stage singing one of our songs, at the same time having a naked girl crucified to a cross. The kid was out of line of sight from the girl, but everybody else could see them both. I thought it was a weird little science project without actually breaking the law.’

All of which begs the question as to what the purpose of this ‘weird little science project’ was. The key lies, perhaps, in his identification with the Child Catcher: ‘I went through a lot of things as a kid, so I think that as an adult, I kind of became the things that terrified me as a kid,’ Marilyn explains, telling of how he felt he was becoming the character from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. It’s the same process whereby the young Brian Warner – who was terrified by his teachers at the Christian Heritage School, predicting the imminent arrival of the Antichrist – transformed gradually into the Antichrist Superstar.

It’s also the same process that Charlie Manson described as ‘getting the fear’ – a technique he developed to endure his long stays in reform schools and penal institutions, where authority was imposed by guards and fellow inmates by inducing fear. Charlie knew he had to make use of his wits and charisma. His strategy was to reflect the fear of those around him back at them, to become so confident that their aggression melted into insecurity and fear. When Charlie was released in 1967 he started preaching this doctrine to his eager hippy disciples, and some believe the Tate-LaBianca massacres were actually attempts by Charlie to give ‘the fear’ to the whole straight Establishment (a strategy that had special resonance to the flower children, as ‘getting the fear’ was also a term for acid-inspired paranoia).

Similar ideas run through modern satanic doctrine – Satanism in itself being a way of manipulating the fears and inadequacies of modern society. It’s the same sentiment expressed in the liner notes to Portrait of an American Family, where Marilyn Manson claims that the fears fed to the Spooky Kids ‘in your sugary breakfast cereals . . . have hardened in our soft pink bellies’.

The Child Catcher is not the only children’s entertainment figure to feature in Marilyn Manson’s world. Characters from kids’ cartoons that blend fun and fear, like Scooby Doo, appear in early graphics and oblique lyrical references. (The van used by the show’s heroes is called the Mystery Machine – the closing track on Portrait of an Anerican Family, entitled ‘Misery Machine’, is about journeying down ‘Highway 666’ to the occult world of black magician Aleister Crowley.)

He also makes frequent references to kids’ shows where lurid visuals and surreal plots enter the realms of the hallucinatory and the psychedelic, like Sid and Marty Kroffts’ early 1970s Saturday-morning show Lidsville. (The Great Hoodoo, the evil wizard from Lidsville, features heavily in ‘Dope Hat’ – a musical exploration of the hazards of LaVeyan showmanship and losing identity, whereby the sorcerer/showman can become trapped into trying to satisfy the expectations of a parasitic audience.) The Kroffts’ prolific output of kids’TV during the 1970s has now become cult viewing, particularly the surreal shows which blended live action with huge lurid puppets – like Lidsville, with its world filled with hats, or H.R. Pufnstuf, an orange dragon in a cowboy outfit.

Marilyn is also enchanted by the subversive undertones of Dr Seuss’s Cat in the Hat, drawing an unlikely parallel between the title character and Satan. ‘The character of the Cat in the Hat is not unlike the character of Willy Wonka,’ he explained, ‘which is also similar to a character like Antichrist Superstar, who is taking the role of the fallen angel. The Cat in the Hat – he was doing his thing the way he wanted to do it, and he wasn’t playing by the rules. Neither was Willy Wonka. The antihero in literature is the one I’ve always identified with.’ The Cat in the Hat therefore becomes an icon for productive chaos and playful defiance of authority.

TAKE IT SLOWLY, THIS BOOK IS DANGEROUS . . .

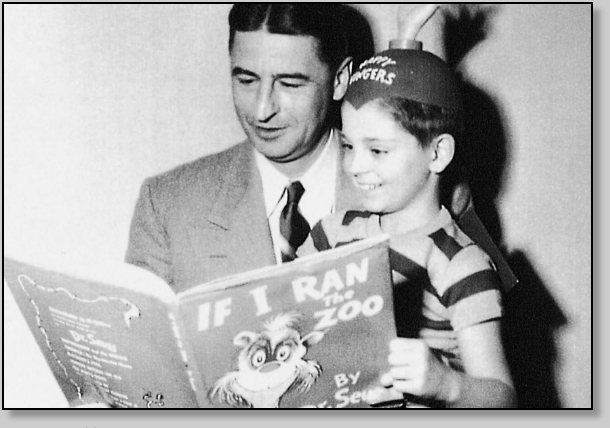

Theodor Seuss Geisel is better known to millions of Americans as Dr Seuss, author and illustrator of Green Eggs and Ham and, his greatest creation, The Cat in the Hat. Born in 1904 in Massachusetts, of German descent, Seuss’ anarchic artistic style and surrealistic plots have made him among the best known and loved children’s authors in the world. Described by Life magazine as ‘a devilish puritan’, the ‘Dr Seuss’ pseudonym was originally invented so he could keep writing for his college newspaper after he was busted for drinking during Prohibition. He began his career using his talents in the advertising industry, illustrating a highly successful bug spray campaign in his distinctive style. As a macabre sideline he manufactured stuffed creatures from his imaginary world, using parts from dead animals to construct them like some kind of Sesame Street-Frankenstein.

When Dr Seuss finally turned his hand to writing a children’s book in 1937, it was not an immediate success. He approached 27 publishers, all of whom rejected his work as too fantastic and lacking in the solid moral message they demanded, before publishing via an old schoolfriend. Seuss’ books did carry a moral message, but it was not necessarily one most adults were comfortable with. He preached that the imagination was sacred and should be protected at all costs, and that anarchy or absurdity could be positive things. This instantly connected with children – and, as long as the kids were reading, parents were happy.

Dr Seuss’ newfound success was interrupted by the outbreak of war in Europe. His fierce devotion to freedom – and determination to show he was a good American who renounced his German roots – inspired him to become a political cartoonist, urging the US to declare war on the Nazis. When America did enter the war he became a propagandist, working alongside the famous animator Chuck Jones on cartoons starring Private SNAFU (G.I. slang for Situation Normal All Fucked Up). Aimed at ordinary G.I.s, the cartoons used risqué situations and strong language to get their message across. Seuss’ opposition to the Nazis was heartfelt, and after the war he described the Hitler Youth – antithesis of his ideals of imagination and liberty – as ‘the worst educational crime in the entire history of the world’.

Dr Seuss designed the sets, wrote the lyrics, and collaborated on the script for the 1951 film The 5,000 Fingers of Dr T, one of his few flops. The story featured Dr Terwilliger, an evil piano teacher who wants to enslave five hundred children to play his giant piano. Full of familiar Seuss themes, like taking the side of freedom against duty, it was too darkly weird for mainstream audiences. In 1957, however, he published The Cat in the Hat, whose creation he described as ‘like being lost with a witch in a tunnel of love’. Generations have fallen in love with this surreal fable. ‘The Cat in the Hat and Theodor Geisel were one and the same,’ said a friend, both being characters who ‘delighted in the chaos of life, delighted in the seeming insanity of the world around him because he understood that in the long run, order could be made of that chaos, that you could enjoy it, you could have the thrill of it, become a larger, better person for having experienced it’.

Theodor Geisel aka Dr Seuss on the set of The 5,000 Fingers of Dr T. with the film’s child star Tommy Rettig.

Seuss never lost his impish mischief. In his Dr Seuss ABC Book, a collection of surreal rhymes designed to teach young children the alphabet, the original subversive entry for ‘X’ was sadly never used: ‘Big X, Little X, XXX, Some day kiddies, You will learn about sex.’ Perhaps there’s some justification for Marilyn Manson making comparisons between Dr Seuss and The Bible. Both are bestsellers – over 400 million Dr Seuss books have been sold to date, and it’s estimated that one in four American children receives one as their first book. But, while The Bible teaches obedience and repression, Seuss preaches the virtues of liberty and chaos. And while Christianity spent much of the Middle Ages suppressing and monopolising literacy, Dr Seuss has earned the title of ‘the man who taught America to read’.

One of the most disturbing aspects of Manson is his exposure of the darkness inherent in childhood fantasies – in the case of Smells Like Children, one of the main reference points was the film based upon Roald Dahl’s novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. As he described, ‘The glue holding all this together was dialogue from Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory that had been taken out of context to sound like sexual double entendres.’

DEATH METAL AND DISNEY WORLD

Few American states represent the opposing extremes of American culture so well as Florida, where the young Brian Warner gradually transformed into Marilyn Manson. As a favourite destination of retiring pensioners and tourists, the ‘Sunshine State’ is also the gateway for the drugs trade from South America, with all of the inner-city crime that it attracts. Disney World opened there in 1971, as a larger-scale version of its parent Disneyland in California. Surprisingly, its architect Walt Disney, is held up as a visionary by members of the Church of Satan because of his creation of controlled environments (like Disney World) where robots and models replace inadequate humans.

Resolutely conservative, not least because of its large elderly population, Florida supports an unexpectedly vibrant music scene. It has become the spiritual home of death metal, the extreme rock style that combines growled vocals, overheated guitars and gore-fixated themes, and also bred the controversial, porn-fixated Miami rappers 2 Live Crew, who Marilyn credits with inspiring him, as a white performer, to come up with an act more subversively offensive than their porn-fixated adult nursery rhymes. Later, musing on the success of his ‘science project’ in a radio interview, he held Florida’s social climate partially responsible. ‘I think it’s the environment that creates bands like us, because it’s so conservative there that there is a need for something like this.’

In fact, the Antichrist Superstar regards Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory as ‘one of the greatest films of all time’, recalling watching it ‘obsessively while eating bags and bags of candy’. As the title change from the original novel suggests, the cinematic version concentrates more on the fearsome, fun-loving figure of Willy Wonka. The basic story is that a collection of cartoonishly-grotesque children win a competition to take a tour of Wonka’s miraculous chocolate factory, each with the prospect of inheriting it. All of them suffer a sickly sweet death through misadventure, except the hero, Charlie Bucket, who graduates as Wonka’s apprentice. It is a delightfully cruel, candy-coated fable about temptation.

Gene Wilder (at rear) in the title role in Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

‘I thought Willy Wonka represented the devil,’ confirmed the singing Satanist, ‘and I’ve always been attracted to the bad guy. Why was he the bad guy? Later I realised that it’s all according to perspective. If you’re standing with the bad guy, then somebody else is the bad guy. But I always thought Willy Wonka represented that dark side, because he lured children with the sweets and things that were forbidden.’ It was a role Brian Warner would adopt in the guise of Marilyn Manson, enticing a generation of Spooky Kids toward ‘things that were forbidden’.

BLOOD AND CHOCOLATE

A British writer of Norwegian descent, Roald Dahl was moved to creativity by his experiences as a fighter pilot in the Second World War. Sitting alone in the cockpit, waiting to kill or be killed, proved darkly inspirational to Dahl’s lively, wicked imagination. After an accident left him badly burnt, ending his airforce career and leaving him prone to chronic pain for the rest of his life, Dahl began writing propaganda before publishing his first collection of short stories after the war. The novel Sometime Never followed, describing the end of the world with detached, acidic humour. He later disowned it – according to friends the book was ‘Dahl uncensored’, revealing too much about its creator.

Dahl became known for his punchy, cynical short stories, often steeped in black humour, sometimes containing a dark moral. One critic accused him of ‘morbidity, irresponsible cruelty and macabre realism’ – when he brought these aspects to children’s fiction, however, Dahl really found his audience. Significantly, he never restrained his grislier instincts for the younger readership, and always took the side of his child protagonist, often an abandoned or mistreated orphan, against a vast, unfriendly world. He remembered how children thought, knew they were not the cherubs that moralists liked to think they were, but little devils who shared his fascination with strangeness and delight in extremes.

‘Something that will shock an adult won’t shock a child,’ commented Dahl on writing for children, ‘they’ll roar with laughter. You can become as crude as you like, as coarse as you like, almost as cruel as you like, as long as there is a burst of laughter at the same time.’ What one critic described as his ‘notoriously subversive children’s books’ made Roald Dahl an internationally famous author – most notably for Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and James and the Giant Peach.

Dahl’s personal life was marred with tragedy – serious illness and untimely death plagued his family – which doubtless coloured his dark view of the world. One of the ways Dahl coped was with his macabre sense of mischief. Once, at a dinner party, he handed around a small object, making sure all the guests had scrutinised it in detail before identifying it as a piece of his hip, removed in a recent operation. ‘He liked to shock,’ said his daughter Ophelia. ‘That was important because he felt life was shocking. He also thought it was too easy to look at all the lovely things in life, though he could do that too, he just didn’t think people wanted to read about that.’