Chapter Nine of The Long Hard Road Out of Hell opens with a quote from Aleister Crowley, the twentieth century’s foremost black magician. It is his holiest (or unholiest) rule – ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.’The chapter is entitled ‘Rules’, and contains three sets of questionnaires, a spoof of the bargain-basement self-psychoanalysis tests found in tacky magazines. The first is designed to tell if you’re a drug addict, and the last question suggests, ‘If you make this book into a game and do a line every time drugs are mentioned, then not only are you an addict but you may be dead.’

He’s not kidding. Brian Warner may have been a slow starter, not familiarising himself with the world of narcotics until he was nineteen or twenty in a nation where pre-pubescent crack addicts are a growing problem, but once he adopted the mantle of Marilyn Manson he made up for it with a vengeance. The sheer volume and variety of drugs detailed in his autobiography is breathtaking, even by rock’n’roll standards – we witness his initiation into LSD and cocaine, as well as his introduction to others of such exotic practises as smoking human bones and snorting sea monkeys. In classic style, he is destined to crash and burn. The penultimate chapter, which opens with him coming round in a hospital to the words, ‘This man is deceased,’ covers the near-fatal consequences of Marilyn Manson’s plunge into excess.

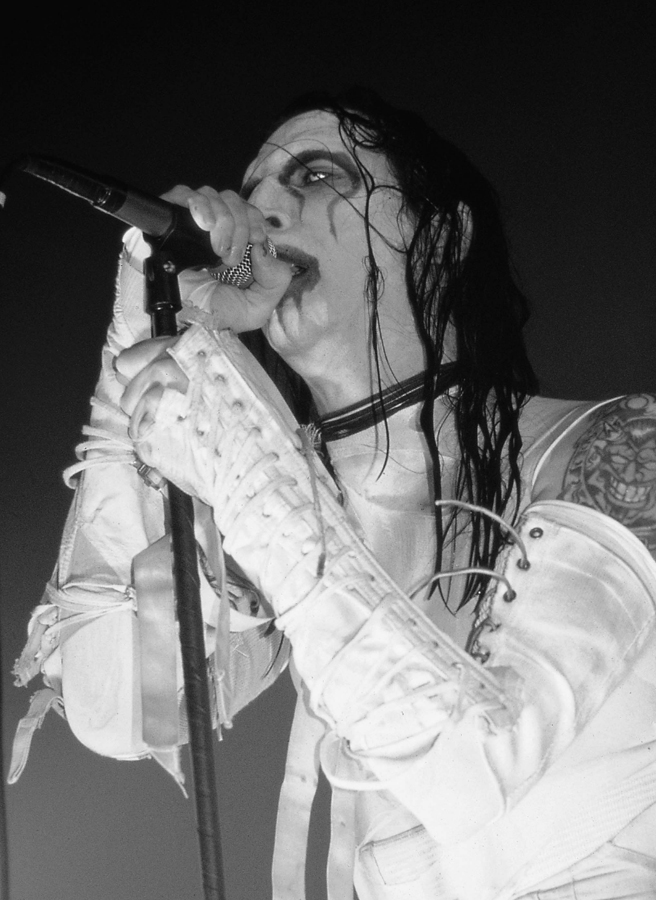

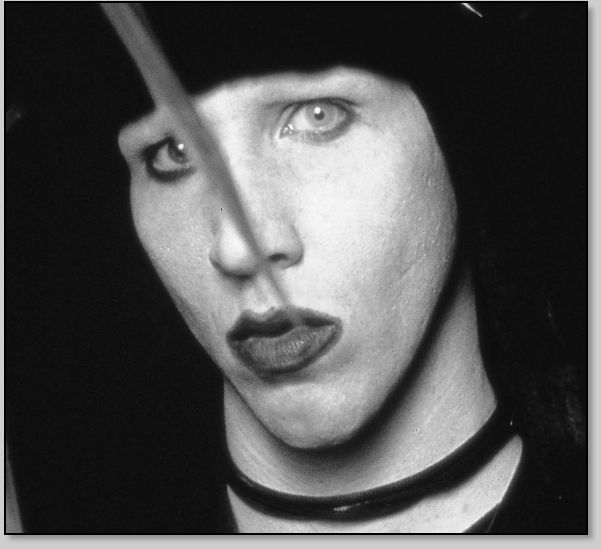

Fast forward three years, and the album that resulted from his hellish New Orleans drug frenzy, Antichrist Superstar, has propelled the band to international fame. Marilyn is on stage at the Big Day Out, Britain’s biggest heavy metal event of 1999. A huge sign lights up behind him as he stalks towards the audience, leering like a preacher in predatory mode. The sign says ‘DRUGS’. ‘I had a dream,’ the Reverend Manson announces to the assembled congregation of howling rock fans. ‘I was drowning in a sea of liquor, I was washed up on a beach made of cocaine, the sky was made of LSD, the trees were made of marijuana, and God came down from heaven. He asked me to spell his name, and I asked him how. He said, “Give me a D, give me an R . . . U . . . G . . . S . . .” What does that spell?’

COFFIN NAILS

Cartoon from a seventeenth-century anti-smoking pamphlet depicting the habit as a devil.

‘Everybody take drugs and we’ll be fine,’ Marilyn Manson once announced on a live talk show, but even he has limits. With typical perversity, he takes a stand against tobacco, one of the most widespread legal drugs. ‘I don’t believe in cigarettes,’ he testifies, ‘in fact when people smoke, I can’t hear what they’re saying. I’ve fine tuned myself to shut out the words of smokers, so I miss out on a lot of conversations.’

But Marilyn does have a point, and he’s in good company. In 1604, as the habit was taking hold of the Western world, James I issued a pamphlet attacking tobacco. The royal anti-smoker described the habit as ‘a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and the black stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless’. But not even the King of England could prevent the spread of what was the perfect capitalist product. Tobacco is cheap to produce, easily distributed and very habit-forming. Its only minor drawback is a tendency to kill the customer. Even when alcohol, the drug with the longest tradition in Western culture, was banned in the US between 1920-33 on health and moral grounds, tobacco remained on sale.

In a joke as black as a cancer victim’s lungs, governments take their revenue and turn a blind eye while tobacco companies continue to make a killing. Corporations make huge profits in the face of all the evidence that, as drugs expert Richard Rudgley puts it, ‘tobacco consumption is directly responsible for more deaths than all the other legal and illegal psychoactive substances put together.’ It all makes tobacco companies look like the world’s biggest drug dealers, while governments resemble the corrupt police who protect them in return for kickbacks. The really crazy part is that, in terms of actual effects, smokers get almost nothing for their money in comparison to virtually every equivalent drug. It’s easy to see Marilyn Manson’s point when he says, of his tobacco ban on tour, that ‘the smoking thing is just common sense, you know. Look what happened with Clinton and his cigar. So I think if you have to have some morality, I believe in not smoking.’

THE ART OF ADDICTION

Marilyn Manson is in little doubt that ‘rock and roll is about drugs’. A hundred years or so ago, many people would have said the same about poetry – or perhaps even all of the arts. Many of the Romantic poets were inspired by laudanum, a liquid preparation containing opium. English Romantic Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote his masterpiece ‘Kubla Khan’ under the influence of opium, a drug that later ruined his health. His friend Thomas de Quincey became famous in 1820 for the novel Confessions of an English Opium Eater, vividly describing his own experiences as a drug addict. The novel was highly regarded by the French Decadents, and indulgence in narcotics became an integral part of their lifestyle. Opium and hashish were still very much associated with the mysterious East, and visiting the squalid opium dens and exclusive hashish clubs that sprung up all over Europe in the nineteenth century was an adventure with the illicit flavour of the Orient.

The most decadent drug of all, however, was absinthe, a powerful alcoholic spirit containing strange herbs supposed to have curious, mind-altering properties. Nicknamed ‘the green fairy’, few decadent poets did not fall under its spell and numerous poems of the period are dedicated to this legendary liquor. Paul Verlaine wrote, ‘For me, my glory is but a humble ephemeral absinthe/ drunk on the sly, with fear of treason/ and if I drink no longer,/ it is for good reason!’ Oscar Wilde was of the opinion that ‘A glass of absinthe is as poetical as anything in the world. What difference is there between a glass of absinthe and a sunset?’ he asked, explaining that, ‘After the first glass, you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see things as they are not. Finally, you see things as they really are, which is the most horrible thing in the world.’

In a familiar pattern, absinthe was officially suppressed at the turn of the century and declared illegal in many countries. But it was not outlawed everywhere, and the green fairy recently entered the world of rock’n’roll when it was served at the 1999 annual awards held by UK heavy metal magazine Kerrang! Unable to resist this most notoriously decadent of drinks, Marilyn Manson brought a supply of absinthe back from the Czech capital of Prague in late 1999 (the US having banned the green fairy in 1912). As it says in the punning Marilyn Manson subtitle for the remix of ‘I Don’t Like the Drugs (But the Drugs Like Me)’ – ‘Absinthe Makes the Heart Grow Fonder.’

‘Absinthe is death’ proclaims this anti-absinthe propaganda issued by the French Government in the early-twentieth-century.

DRUG PARANOIA

The escalating ‘War on Drugs’ waged by governments during the twentieth century, particularly those of the USA and the UK, has been met only by an escalating drug problem. As politicians take an increasingly punitive hard line, so the number of addicts continues to spiral. The failure to eradicate drugs is unsurprising in view of the near universal pattern of use and abuse throughout human history. Recreational drug use can be traced back to the Stone Age, and it is very difficult to find a single culture that does not indulge in some kind of narcotic. Even the Eskimos, sometimes cited as drug-free, make recourse to a fungi with hypnotic properties.

Another reason for the failure of the War on Drugs is its mammoth hypocrisy. Many young people react with cynicism to lectures on the evils of drugs from politicians with cigars in their mouths, whiskey-swilling clergymen and police officers who can’t get going in the morning without a nice strong cup of coffee. As John Strausburgh notes in The Drug User, ‘President Chester A. Arthur was noted for his love of alcohol and narcotics. Grover Cleveland drank heavily, used ether and cocaine, and his wife, Frances, appeared in ads for a pharmaceutical company. While publicly supporting Prohibition, Warren Harding, and even the supposedly abstemious Herbert Hoover drank bootleg liquor behind closed doors in the White House. John F. Kennedy was rumoured to indulge in occasional recreational drug use, although it’s never been substantiated, and he was most certainly a great lover of tobacco. Reagan was given morphine after undergoing colon surgery, and was reported to have enjoyed it.’

The true depth of the Establishment’s hypocrisy is breathtaking. While William von Raab, head of US Customs, was insisting, ‘This is a war, and anyone who even suggests a tolerant attitude towards drug use should be considered a traitor,’ journalists – like Gary Webb, in his acclaimed book Dark Alliance – were suggesting links between the CIA and the explosion of crack cocaine on America’s streets in the 1980s. Webb claimed that the CIA were, at the very least, turning a blind eye to Nicaraguan Contra rebels who were financing their war by smuggling cocaine to the US.

This was strangely in keeping with the CIA’s schizoid attitude to drugs. In the 1950s and early 1960s, their notorious MKULTRA domestic spying and research operation had dosed at least 1,500 military personnel and countless civilians with LSD, MDA and other hallucinogens, often under duress or without the guinea pig’s permission. Unsurprisingly, after these revelations, some have seen the Establishment’s double-edged attitude toward drugs as symptomatic of a conspiracy. In their book Acid Dreams:The CIA, LSD, and the Sixties Rebellion, Martin Lee and Bruce Shlain suggest the CIA deliberately introduced the hippies to acid in order to silence anti-Vietnam War protests. Certainly, many of the foremost figures in the movement made comments to confirm the suspicion.

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg wondered, ‘Am I the product of one of the CIA’s experiments in mind control? Have they by conscious plan or inadvertent Pandora’s box let loose the whole LSD fad on the US and the world?’ Acid guru Timothy Leary agreed that ‘The LSD movement was started by the CIA. I wouldn’t be here without the CIA.’ Naturally, many hippies liked to think the CIA’s plan had backfired, like Beatle John Lennon who insisted, ‘We must remember to thank the CIA and the army for LSD. They invented LSD to control people but what they gave us was freedom.’ Others were more cynical, like author and drug icon William S. Burroughs, who observed, ‘LSD makes people less competent. You can see their [the CIA’s] motivation for turning people on.’ His view was given extra credence when the FBI claimed, after Timothy Leary’s death, that the hippie high priest had been one of their regular informants on the drug culture.

It’s a classic Marilyn Manson provocation, using a mock-Christian revivalist sermon to advocate that great twentieth century taboo, recreational pharmaceuticals, with a sly nod to the declamatory nature of a rockshow’s traditional audience-participation section. But is there more to this than gleefully irresponsibility and crude shock tactics?

While few can claim to have done so in such outrageous fashion, Marilyn Manson is certainly not the only person to have linked drugs with religion. Oxford anthropologist and drug expert Richard Rudgley, observes in the introduction to his Encyclopaedia of Psychoactive Substances that, ‘The recreational use of hallucinogens in our own society would be unthinkable in other cultures who value these kinds of substances as gifts from the gods. Our largely secular use of psychoactive substances is something of an anomaly in the whole scheme of human history and that they could have some sacred function is inconceivable to many people in our society.’ In other words, in the great scheme of things, treating drugs as merely a bit of fun rather than a mystical experience is almost an anomaly.

In his introduction to The Drug User, John Strausberg suggests that this might be where the West’s drug problem begins. ‘Some anthropologists and ethnologists believe that modern American culture has difficulties with drugs and alcohol precisely because it has no ritual context with which to control and moderate their use. To the extent that ours is a religious culture, it is mostly Puritan Protestant, with a strong minority presence of Roman Catholicism. It’s a tradition that frowns severely on getting high in any way – even getting high within a religious, ritual context, even without the use of drugs.’ Priests and holymen in early societies played the role of politicians and lawyers in our own culture, deciding which drugs were acceptable and monitoring their use. Some anthropologists even suggest that early cultures did not develop drugs to explore religion so much as invent religion to explain the psychic properties of drugs.

The English writer Aldous Huxley (author of Brave New World, cited by Marilyn Manson as an influence) was a pioneering thinker in this area. He declared that ‘the pen is mightier than the sword. But mightier than either the sword or the pen is the pill’ in a 1958 article for The Saturday Evening Post entitled ‘Drugs That Shape Men’s Minds’. In this bold feature, Huxley argued that it would benefit Western culture if we were to abandon the idea of drugs as a law and order issue, and return to regarding them as sacred.

‘Those,’ wrote Huxley, ‘who are offended by the idea that the swallowing of a pill may contribute to a genuinely religious experience should remember that all the standard mortifications – fasting, voluntary sleeplessness and self-torture – inflicted upon themselves by the ascetics of every religion for the purpose of acquiring merit, are also, like the mind-changing drugs, powerful devices for altering the chemistry of the body in general and the nervous system in particular . . . That men and women can, by physical and chemical means, transcend themselves in a genuinely spiritual way is something which, to the squeamish idealist, seems rather shocking. But, after all, the drug or the physical exercise is not the cause of the spiritual experience; only its occasion.’

Aldous Huxley certainly used (and enjoyed) psychedelic drugs, notably mescaline – the powerful hallucinogenic drug derived from the peyote cactus used for thousands of years by native Mexican shamen. However, Huxley stressed caution, and his interest in a religion based upon the drug experience was largely theoretical. There were, however, pioneers (perhaps even prophets) prepared to throw caution to the wind. Prominent among these was Aleister Crowley, ‘the Great Beast 666’, who, legend has it, first introduced Huxley to mescaline in Berlin at the height of the pre-war Nazi era.

Crowley saw himself as the founder of a new religion, called Thelema – or ‘Crowleyanity’ – which would eclipse Christianity. This most unorthodox of messiahs preached that psychoactive drugs were the (un)holiest of sacraments, second only to sex, and consumed a catalogue of drugs that makes even Marilyn Manson’s itinerary of indulgence look modest by comparison. In one of the best known passages in The Book of the Law, the bible of Crowley’s creed, the faithful are instructed, ‘To worship me take wine and strange drugs whereof I will tell my prophet, & be drunk thereof! They shall not harm thee at all. It is a lie, this folly against self.’

However, the Great Beast emphasised that drugs, like sex, were spiritual paths to enlightenment and indulging in them merely for pleasure, or as an idle diversion, was blasphemy in Crowley’s eyes. In this light it’s difficult to see much common ground between this deviant English mystic, who wanted to ‘open the veils of matter’, and his modern disciple Marilyn, who just seems to be walking the well-worn path of rock excess. But look more closely at his drug use as described in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, and there are hints that he regards it as more than just a risky recreational pursuit.

Brian Warner’s initiation into a form of ‘Satanism’ coincided with his initiation into the world of narcotics. Both came courtesy of childhood friend John Crowell (a name suggestively similar to Crowley), or, to be precise, his older brother. Crowell’s brother was the archetypal white-trash teen Satanist, the kind of guy police might refer to as a ‘stoner’, and someone whom Anton LaVey would dismiss as an asshole. In Crowell’s squalid satanic shrine, the icons are Ozzy Osbourne posters, the religious hymnals are played by Black Sabbath, and the sacred text is the mass-market paperback edition of The Necronomicon. The grown-up Brian Warner would later describe the dingy lair as ‘exactly what you’d expect from a rural wastoid with a penchant for Satan’.

Most importantly, however, Crowell’s unholy sacrament – occupying pride of place on his black altar – was a bong, loaded with marijuana and fortified with Southern Comfort. The young Brian’s initiation into teen Satanism and illicit substances climaxes with him passing out. ‘Then I threw up. Then I threw up again. And again. But as I knelt doubled over above the toilet, I realised that I had learnt something from the previous night: that I could use black magic to turn the lowly lot life had given me around – to attain a position of power that other people would envy and accomplish things that other people couldn’t. I also learned that I didn’t like smoking pot – or the taste of bongwater.’

THE BEAUTY OF THE BEAST

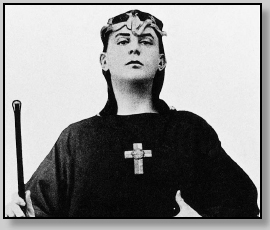

The Great Beast Aleister Crowley.

Asked by a fan about the significance of ‘the Abbey of Thelema’ mentioned in the song ‘Misery Machine’, Marilyn Manson responded, ‘It’s something that Aleister Crowley had to do with, if you read any of the stuff that he wrote. A notorious antichrist from the 1800’s who died of drug addiction unfortunately. But a great writer.’ Crowley was a philosopher and occultist whose influence continues to grow in the present day (not least upon Manson). He remains a controversial figure and even among his growing legions of admirers, there are profound differences of opinion on the nature and significance of this extraordinary man’s philosophy. An examination of Crowley’s career reveals some interesting parallels with that of Marilyn himself.

Born Edward Alexander Crowley, to an English brewing family in 1875, his poisonously pious parents sent him to a church school where the religious zeal of the teachers was matched only by their brutal discipline. Like Brian Warner a century later, Crowley responded to his religious education by rebelling. His mother responded by dubbing her disobedient son ‘the Beast’, a name that echoes the Satanic creature in the last book of The Bible who heralds the end of the world. Crowley embraced the insult with pride. He attended Trinity College, Cambridge in 1895, while the Decadent movement was reaching its height in Paris. The young Crowley adopted the lifestyle of the classic Decadent, experimenting enthusiastically with sex and drugs while penning scandalous poetry. But while most Decadents flirted fashionably with the occult, Crowley hurled himself headlong into the black arts as a way of striking back at the Christian faith that blighted his childhood.

He never graduated but began travelling, exploring Eastern religions and investigating the occult lodges that had sprang up all over Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1904, while on honeymoon with his first wife, Crowley experienced a revelation in Egypt that gave his thus far aimless life a definite direction. He claimed that his Holy Guardian Angel (who some – including, on occasions, Crowley himself – have perceived as Satan) dictated to him The Book of the Law. More than a mere magical grimoire, Crowley claimed it was the bible for a new religion that would destroy Christianity. A new aeon was dawning, the Aeon of the Ancient Egyptian war god Horus, when everybody would become attuned to their true selves. And Aleister Crowley, the Great Beast, believed himself the prophet of this new age.

During his life Crowley had few converts to his revolutionary faith, but those who did follow the decadent guru were often talented, influential or powerful individuals in their own right. The Beast was never short of the sexual partners he required for his religion’s weird rituals. As far as most people were concerned, however, he was just a colourful cad, dubbed ‘the Wickedest Man in the World’ by the press but largely forgotten by the time of his death in 1947. Since his death, assessments of his career have varied. He could be monstrously childish, and legends that most of his followers were left insane, financially broke, or in an early grave have their basis firmly in fact – but Crowley was also possessed of a brilliant mind, vast vigour and a magnificent independence it’s difficult not to admire (at least from a distance).

There are more converts to Crowley’s religion today than there were in his lifetime, mainly in the various modern lodges of the Ordo Templi Orientis, an occult order once headed by the Beast. Increasingly, however, Crowley attracts admirers from outside the occult scene who regard him as a stormtrooper against the last bastions of repressive nineteenth-century Christian morality, a writer whose deviant philosophy, scandalous lifestyle and obscene poetry demonstrate a new way of life.

Like Marilyn Manson, Crowley became a character in one of his own decadent fantasies and refused to recant. Marilyn’s description of Crowley as ‘a writer’ implies that he regards the Great Beast as an artist rather than a prophet, but the following comments suggest an increasing interest in The Book of the Law: ‘I don’t care if something’s good or bad or if it’s Christian or anti-Christian – I want something that’s strong, something that believes in itself’ mirrors very strongly, if less extremely, the infamous Crowleyan pronouncement that ‘I want none of your faint approval or faint dispraise; I want blasphemy, murder, rape, revolution, anything bad or good, but strong.’

‘I think every man and woman is a star,’ Marilyn Manson would later claim. ‘It’s just a matter of realising and becoming it. It’s all a matter of willpower.’ This is almost pure Crowley, quoting one of his more famous maxims and demonstrating a close familiarity with the Great Beast’s work. In turn, Crowley’s description of himself following his elevation to the occult rank of ‘Ipsissimus’ bears much comparison with the way Marilyn Manson looked back upon Brian Warner upon completion of Antichrist Superstar. ‘I am myself a physical coward,’ wrote Crowley with disarming self-abasement, ‘but I have exposed myself to every form of disease, accident, and violence; I am dainty and delicate, but I have driven myself to delight in dirty and disgusting debauches, and to devour human excrements and human flesh. I am at this moment defying the power of drugs to disturb my destiny and divert my body from its duty . . . Yet I have mastered every mode of my mind, and made myself a morality more severe than any other in the world if only by virtue of its absolute freedom from any code of conduct.’

This passage may lack the biblical grandeur of Crowley – indeed, the author displays a characteristic decadent tendency to wallow in the sordid – but Marilyn is obviously implying that this experience had some darkly spiritual significance. That implication is even stronger in his description of his first LSD trip in Florida during 1990. Manson doesn’t just describe a bad trip but a journey into his own past and future, haunted by ominous portents, the nightmare journey of a pop-culture shaman into his own underworld. He finds himself screwing Nancy, a girl previously dismissed as a psycho, who, in his hallucinatory world, becomes increasingly demonic. ‘This is it,’ he writes of that moment. ‘I’m screwing the devil. I’ve sold my soul.’ While it lacks the formal rites and robes, what Marilyn describes is classic Crowleyan sex magic, a contemporary demonic pact.

Aleister Crowley died in England 1947, still consuming enough heroin to kill a whole squad of guardsmen. It’s easy to believe that, had the Great Beast’s ghost been haunting the Big Day Out in 1999, he would have given his blessing to Marilyn Manson’s brief, blasphemous sermon. It’s less certain what Crowley might have made of the song that followed it, ‘I Don’t Like the Drugs (But the Drugs Like Me)’ – as more than one critic has commented, the song is a pithily witty summation of anyone in the thrall of a drug habit.

Crowley’s attitude to drugs reflects some of the harshest aspects of his creed, dismissing those not strong enough to conquer addiction as ‘slaves’ in his Book of the Law: ‘Pity not the fallen! I never knew them. I am not for them. I console not: I hate the consoled and consoler. I am unique, a conqueror. I am not of the slaves that perish. Be they damned and dead! Amen . . .’

Such sentiments are broadly reflected in Marilyn’s own views, his point being that drugs are not the problem – it’s the people who use them, suggesting that addicts give purely recreational drug users a bad name. This recurring line – the difference between ‘use’ and ‘abuse’ – is a radical statement at a time when orthodox wisdom insists all illicit drug use is automatically ‘abuse’. As outlined by Church of Satan High Priest Anton LaVey (himself vehemently anti-drugs) in The Satanic Bible, Marilyn Manson’s policy is ‘Indulgence . . . NOT Compulsion.’

Satanism as a creed worships the flesh and its pleasures, and is almost obliged to exhibit sympathy to sin. But earthly pleasures pursued to excess are rarely pleasurable, and often lead to dependence and self-destruction – blasphemy to a creed that preaches independence and self-empowerment. To address this problem, LaVey emphasised that excessive self-indulgence is merely masochism in a perverse guise. When the Church of Satan was founded in San Francisco during 1966 as ‘flower power’ was reaching its height, LaVey asserted that those hippies who felt obliged to take drugs to be cool were no freer than the straight folk who avoided drugs to be respectable.

As the decades passed, the Church of Satan’s disdain for the hippies advanced into hatred. Whilst none of the Church’s central tenets changed, some of them were expressed more aggressively. An article was published in a 1994 edition of The Black Flame, the Church of Satan’s International Forum, by a Satanist calling himself Azazel, entitled ‘Drugs and Natural Selection’: ‘The government has no right or responsibility to prevent any adult of legal age from consuming any drug, no matter what the personal detriment is. This freedom to choose is a natural human right. Drugs, however, should be neither condoned nor advocated, as they are part of a natural screening process separating the weak from the strong which greatly contributes to natural selection and population control. Overdose, lack of direction, apathy, listlessness, addiction, and all the other wonderful side effects of drugs allow these individuals to be exploited, for by such behaviour they are prey.’ Natural selection – the idea that the strong will thrive while the weak will perish – is a dominant force not just in the animal world but in human society, according to believers in Social Darwinism, one of the key tenets of The Satanic Bible.

Azazel’s opinions reflect those of an increasing number of members within the Church of Satan. Contrary to myths spread by Christian fundamentalists that condemn Satanism as an international drugs cult, the ethos of the CoS was traditionally anti-narcotics. This has caused some recent tension within the movement, since two icons revered by modern members – Aleister Crowley (who LaVey regarded as a ‘druggy poseur’) and Charlie Manson – both have reputations as habitual drug users. The fact that the highest profile Church of Satan recruit of the 1990s (namely Marilyn Manson) also had a well-known penchant for narcotics caused severe disquiet.

In reality, Marilyn’s views are not as far from those of Azazel as they may first appear. In one talkshow discussing drugs, he went so far as to say, ‘I think drugs can also work as a bit of Social Darwinism.’ Marilyn’s speculation is especially bold, when one considers his description in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell of how drugs nearly destroyed him during the recording of Antichrist Superstar. He explored this paradox whilst interviewed about the recording of Mechanical Animals, an album littered with references to drugs.

‘The problem with Antichrist Superstar was I was put in a position where I was made very unsure of myself. I was questioning everything I did because no one had any confidence in what I was doing and I was taking so many drugs to ease that misery and frustration. It’s only when you’re in that weak frame of mind that drugs can really hurt you. If you’re a competent drug user than there’s nothing to fear. No drugs were sought out of depression or confusion this time because I was very sure about what I was doing. They were just sought out of enjoyment or decadence. The record was written on drugs about drugs, and it will likely be performed on drugs as well.’

And what of Aleister Crowley, whose survival to the age of 72 on a suicidal diet of drugs was almost a magical act in itself? He had evangelised tirelessly in favour of narcotic indulgence, writing articles under pseudonyms with titles like ‘The Great Drug Delusion’ and ‘The Drug Panic’ and a novel with autobiographical components entitled Diary of a Drug Fiend (echoed, of course, in the Marilyn Manson remix title ‘Diary of a Dope Fiend’). Consciously, Crowley almost certainly saw himself as the novel’s impressive guru character who the weak and neurotic seek for help, while subconsciously he must have felt something in common with those who needed help for their drug problems.

FREAKIN’ AT THE FREAKER’S BALL

One of Marilyn Manson’s more improbable influences are the country-rock act Dr Hook and the Medicine Show, who had two bouts of popularity in the 1970s – early in the decade as raucous druggies, then in the late Seventies as a ‘respectable’ MOR act. Two decades later Marilyn and Twiggy Ramirez listened to the band’s hit ‘Cover of the Rolling Stone’ – a comically plaintive musical plea for fame – in a fashion Marilyn describes as ‘ritualistic’. In his autobiography Manson wonders if he got on the cover of Rolling Stone via his campaign of casual kitsch sorcery, celebrating by snorting coke off his cover picture with the tune playing at top volume when the issue came out in January of 1997.

Like many of Marilyn Manson’s obsessions, Dr Hook hide a subversive message within an apparently harmless shell, their foot-tapping country rock concealing a nest of sex and drug innuendo. The Marilyn Manson live album The Last Tour on Earth features another Dr Hook favourite, ‘Get My Rocks Off ’. ‘The song starts out saying, “Some men need killer weed, some men need cocaine”,’ Marilyn explained, ‘and it goes on to mention having sex with dead people and snorting drugs. They’re the most controversial band that ever existed, and I have to pay my dues by covering their song.’

For even the Great Beast, whose Book of the Law reviled addicts as slaves, was forced at times to confess he wasn’t wholly free from addiction. Cocaine, a drug generally regarded as psychologically rather than physically addictive, was a favourite of Crowley’s (and also of Marilyn Manson’s, featuring prominently in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell). In his ‘magical record’, Crowley wrote, ‘Why is it that one takes cocaine (but no other drug) gluttonously, dose upon dose, neither feeling the need for it, nor hoping to get any good from it? I have found that every time. Three doses, intelligently taken, secure all one wants. Yet, if the stuff is at hand, it is almost impossible not to go on . . . Why take thirty doses (or is it sixty? I haven’t a ghost of a guess) to get into a state neither pleasant nor in any way desirable, but fraught with uneasiness, self-contempt, alarm, discomfort and irritation at the ever present thought of “Hell! Now I have to endure the reaction” while well aware that with three one can get all one wants without one single drawback.’ I don’t like the drugs (but the drugs like me)! . . .

Asked about his favourite subject at school, Marilyn joked that it was ‘health’. It’s easy to dismiss this as another throwaway quip, but it’s true that health industry pharmaceuticals seem to preoccupy him nearly as much as recreational drugs. Mechanical Animals, Marilyn Manson’s most overtly drug-themed album, combines images of narcotic excess with those of surgical sterility. The CD even looks like a pill, while its content plays with the idea that the cure may be as bad as the disease.

Medical themes have long haunted Manson’s material. Hypodermic syringes – simultaneously medical instruments and symbols of illicit drug abuse – figure heavily in early promotional imagery. Marilyn himself has even taken to the stage dressed in bizarre remedial garb. Smells Like Children features ‘May Cause Discoloration of the Urine or Faeces’, an unsettling sampled phone call by a patient concerned about his medication. Diagrams lifted from anatomical texts are the dominant motif in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell. In modern culture, of course, where spirituality has become divorced from drugs, doctors have taken over the traditional shaman’s role in deciding which mind-altering drugs are acceptable for use and monitoring their distribution.

The medical profession has become our culture’s most prolific drug pusher. Aldous Huxley, who was sympathetic to psychedelic drug experimentation, wrote that, ‘In theory, tranquillisers should be given only to persons suffering from rather severe forms of neurosis or psychosis. In practice, unfortunately, many physicians have been carried away by the current pharmacological fashion and are prescribing tranquillisers to all and sundry . . . In the present case, millions of patients who have no real need of the tranquillisers have been given the pills by their doctors and have learnt to resort to them in every predicament, however triflingly uncomfortable.’

This was written in 1958, and few would argue that this pharmacological fashion has not only continued, but progressed to the present point where, as author Elizabeth Wurtzel puts it in her celebrated Generation X book, we all live in the Prozac Nation. It is not just rock stars or counter-cultural rebels who turn to drugs to alleviate mild psychological or emotional discomfort – or even just boredom – but our entire culture that seems to be taking to psychoactive substances. Perhaps we always have. As more than one historian has observed, most of the Middle Ages were experienced in an altered state of mind by a population chronically addicted to alcohol. (Which doesn’t even allow for those at the fringes of society, labelled witches by their persecutors, who made use of narcotics to commune with their unholy gods.)

Another reason for the hallucinatory aura that hung over Medieval Europe was the widespread malnutrition and disease. Many modern magicians follow Aleister Crowley and make recourse to fasting in order to attune their minds to other dimensions. Marilyn Manson, as a band, made deliberate use of psychological trauma during the recording of Antichrist Superstar in order to reach altered states of consciousness. While they never went as far as making themselves deliberately ill, the band’s self-conscious, self-destructive self-indulgence invited physical and mental collapse, and it’s certainly true that there are parallels between the psychological effects of the drugs some people go to great lengths to obtain and the illnesses most of us go to great lengths to avoid. Hallucinations, hyperactivity, even elation, are just some of the sensations that can accompany both sickness and a drug-induced high.

THE SPOILS OF WAR

Of all Marilyn Manson’s health complications, perhaps the most exotic are the results of his father’s military career. As a helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War, Hugh Warner sprayed Agent Orange on the Vietnamese jungles – the most notorious of the highly toxic defoliants used by the US army in the conflict (86 million litres were dropped in all), Agent Orange was designed to deprive the enemy of all cover by killing plant life. The strategy was abandoned in 1970, after disappointing results and mounting popular concern over scientific tests linking the defoliant’s chemical properties with cancers and birth defects.

The 1978 film The Deer Hunter – one of the most powerful statements on the traumatic repercussions of the Vietnam war.

Campaigns by Vietnam veterans to have their illnesses recognised as side effects of Agent Orange continue to this day. Marilyn Manson recalls how the young Brian Warner was obliged to undergo scientific trials, to determine whether his father’s exposure to Agent Orange had resulted in any physical or psychological problems for the boy. ‘I don’t think there were any,’ he observes, ‘though my enemies might disagree.’

National humiliation, particularly in war, is one of the factors that plunges a culture into decadence. The decadence of late nineteenth century Paris followed France’s crushing defeat by the Germans in the Franco-Prussian War. The decadence of 1920s Berlin is directly linked to Germany’s loss of the First World War in 1918. Could there be a link between American decadence – as personified by Marilyn Manson – and the humiliating defeat experienced by the US in Vietnam?

When one journalist commented on Marilyn wearing his pyjamas for an interview, he responded that ‘It was a hospital gown, actually, from when I was hospitalised.’ Rather than relating the nature of that specific incident, he went into a catalogue of past ailments: ‘Well, when I was a child I had pneumonia twice. And I had polyps removed from my rectum. I had to have my urethra enlarged because the hole through which I urinate wasn’t large enough to accommodate the stream I was projecting. I had an allergic reaction to antibiotics once and I almost died. Recently, I was hospitalised for depression and scarification. Self-mutilation. And I’ve had my legs waxed, but I wasn’t in the hospital for that.’

To this already long list of illnesses, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell adds TMJ syndrome (a dysfunction of the jaw, caused by having his tooth punched out) and a heart condition known as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. By high school age, ‘Hospitals and bad experiences with women, sexuality and private parts were completely familiar to me,’ Manson observes, linking sickness and eroticism in a clinical, fetishised manner.

Watching his often alarmingly physical performances, it’s difficult to think of Marilyn Manson as sickly in the conventional sense. But still, disease and medication loom large in his world – possibly because he recognises a universally morbid part of the human condition, the knowledge that disease will end most of our lives while medicine is sometimes the only thing standing in between us and our own mortality. However, it could also be that his excessive, self-indulgent lifestyle has given bad health a very large role in his life.

It’s intriguing to note how disease figured so heavily in the lives of the original decadent artists of the nineteenth century. Edgar Allan Poe, the American writer whose work inspired the movement in France, had a delicate constitution made worse by his chronic alcoholism. Unhappy familial and romantic experiences made him associate feminine beauty with the delicate pallor of fatal illness. In turn, his stories and poetry were filled with frail heroes with ancestral ailments, and unspeakably beautiful women on, or past, the brink of death. These archetypes are the seeds from which the delicate, pale-faced aesthetic of the modern gothic subculture grew.

At the height of the Decadent movement, in 1890s Paris, illness was almost a fashion. The Decadents were particularly attracted to the theory of a medical condition known as neurasthenia. According to Brian Stableford, in Moral Ruins, his anthology of decadent writing, ‘The neurasthenic was a physically weak and over-sensitive individual, likely also to be morally weak, permanently possessed by apathy and spiritual impotence.’ If great sensitivity and a touch of evil were the symptom, or even the cause, of a disease – then might not artistic genius also be a pathological condition?

SONNETS OF SYPHILIS AND SATAN

An archetypally decadent devil illustrating Baudelaire’s masterpiece The Litanies of Satan.

Born in 1821, the Frenchman Charles Baudelaire is regarded as the first poet of the Decadent movement. Heavily influenced by hard-drinking, melancholic American author Edgar Allan Poe, Baudelaire developed a style of poetry that soared effortlessly between the squalor of the gutter and sublime beauty. He embraced a lifestyle that complimented the decadence of his work, haunting the brothels and absinthe bars of Paris, becoming known for his dandified dress and cynical wit. His masterpiece, a collection of poems entitled Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil), appeared in 1857, and generated an immediate scandal, containing verses of morbid sexuality, ghoulish meditation and odes to Satan. He was successfully prosecuted by the French Government for offending public morals, fined, and had six of the poems officially removed from the collection and banned from reprint.

Baudelaire caught syphilis as a young man, which, in its progressive form, caused him increasing pain throughout his life, leading him to seek comfort in opium and alcohol. His poem ‘Voyage to Cytherea’ describes visiting an island sacred to the goddess of love, but finding only a rotting corpse hanging from a gibbet whose ‘heavy entrails flowed down his thighs’. ‘On your isle, O Venus, I found nothing erect but a symbolic gallows, where hung my own image.’ Baudelaire’s poor health, combined with his licentious lifestyle, condemned him to an early grave in 1867. He is now regarded as one of the greatest, if darkest, poets of the modern age, and in 1949 the ban on his most shocking verses was finally lifted, nearly a century after they were written.

‘. . . Would be Decadents were initially prepared to take great pains to cultivate their neurasthenia,’ writes Stableford, ‘or at the very least to be conscientious hypochondriacs. They treasured their symptoms, not only as reflections of the unfortunate nature of the human condition but also evidences of their superiority over the common herd.’And the sick shall inherit the earth . . .