‘The world doesn’t revolve around the sun,’ Marilyn Manson once declared, ‘it revolves around a giant cock. That is what the world is about; it’s about sex. Anybody who doesn’t want to realise that is fooling themselves . . . People are bored because they’ve done everything they can do, so now the fear of death is the only thing that gets them excited. That’s why people have made me into some kind of sex symbol. I’m death on wheels, the way I look.’

Man, as a species, has always had sex on the brain, though the forms it takes have varied over the years. The 1990s have been characterised by a rise in the public profile of fetishism, particularly sadomasochism, springing from its grassroots in the counterculture.

It seems we were all ready for a sex symbol who was ‘death on wheels’ – Marilyn took to the role as if born to it, staking out the unsettling territory between pain and pleasure. The Manson stageshow is a perverse celebration of lust and fury. Even the audience, clad in leather, PVC and rubber, wear their marks of self-mutilation like battle scars. Few images from The Long Hard Road Out of Hell are as simultaneously grotesque and affecting as the photo of the ‘slash girls’ with ‘Marilyn’ and ‘Manson’ carved into their chests.

When Marilyn spoke of ‘a giant cock’ he was referring to the sexual theories of Sigmund Freud, but he might as well have been quoting the occult doctrine of Aleister Crowley. In his book The Magical World of Aleister Crowley, Francis King describes the Great Beast’s strange cosmology: ‘For Crowley . . . the sun was the supreme deity. On earth however he is represented by the phallus, the male sexual organ, which is “the vice-regent of the sun”, “the sole giver of life”. All the universal gods – that is deities such as the gods and goddesses of the moon, of fire, of mountains and of trees – are, it is asserted, but personifications of the penis. Thus the fire-deity is an image of the sun “and a fable of the phallus”; the tree is “but the flowering of the Phallus”, while the moon-deity is an image of the vagina . . . ’

Crowley believed in the occult doctrine that preaches how the cosmos is reflected in the human body, and vice versa. As he also believed that the most profound human experience was sexual orgasm, he reasoned that sex was the central power of the cosmos. This was a central credo of ‘Crowleyanity’ – in the Great Beast’s creed, most religious rituals and magical workings were accompanied – as with oriental philosophies like Tantrism, which Crowley had studied – by sexual acts.

Freud shared Crowley’s conviction that sex was the key to understanding our place in the universe, though he dismissed religion as a symptom of widespread neuroses. Indeed, his later years were occupied by the search for an impulse strong enough to deny the sexual urge, therefore explaining why human behaviour wasn’t solely motivated by sex. Freud came up with an interesting solution: the sexual urge of Eros (Ancient Greek god of lust) was in direct conflict with the death urge of Thanatos (Ancient Greek god of death). Our instinct to reproduce ourselves was balanced by our instinct to die. According to Freud, the interplay between these conflicting instincts, and their development during childhood, determined our adult hang-ups and perversions.

It would be intriguing to know what Freud would have made of Aleister Crowley. As a child, Crowley was heavily disciplined by his strict Christian parents and teachers. As an adult, he responded by turning his sexual urges into the basis of an anti-Christian religion with himself as its prophet. Sex and death figure heavily in Crowleyanity, with its rites of blood and eroticism, as do masters and slaves – Crowley’s cosmology having much in common with Nietzsche’s vision of a master-morality and slave-morality, transcending ordinary ideas of good and evil. Marilyn Manson would later echo this harsh worldview by observing, ‘When you break it down, in life some people like to be abused, and some people like to abuse other people. In reality that’s not such a bad thing, you just have to pick your role in life. Sometimes I’m both.’

Sexual fetishism was evident in many of the rites and ceremonies undertaken by the Great Beast. In 1909, Crowley subjected his new apprentice, Victor Neuburg, to a ‘magical retirement’ – a crash course in the occult that reads very much like a heavily sadomasochistic homosexual fling. As Francis King observes, ‘it is clear that both men had strongly sado-masochistic elements in their make-up – even in the brutal discipline inflicted by Zen Buddhist masters on their pupils there is nothing to compare with the incidents when Crowley beat his pupil with gorse and nettles’. In early 1914, the Great Beast engaged with Neuberg in the ‘Paris workings’, magical rites with the aim of invoking the gods Jupiter and Mercury who, the pair hoped, would provide them with much-needed funds.

These homosexual rites reached an even greater sadomasochistic intensity when Crowley not only beat his disciple, but also bound him with chains and carved a cross over his heart. (Interestingly, however, in acts of sodomy Crowley almost always took the passive role.) One of the climaxes of these rites was a vision of a past life in Ancient Crete – when Crowley was a dancing girl and Neuberg a novice priest, both enslaved as punishment for falling in love with each other. In Crowley’s world of sacred sadomasochism and hallowed whores, we witness a man trying to exorcise his Christian childhood of sexual repression and harsh corporal punishment.

Anton LaVey often described his Church of Satan as an institution designed to occupy ‘the grey area between psychiatry and religion’, a doctrine perhaps best illustrated in its attitude toward sex. Psychiatry sought to ‘cure’ sexual peculiarities or perversions, while religion sought either to suppress (as with Christianity) or disguise (as with Crowleyanity) the carnal urge. The Church of Satan, on the other hand, celebrated fetishes and fantasies as badges of individuality. According to LaVeyan Satanism, individualism is the central factor: the person who indulges in promiscuity in order to take part in the sexual revolution is no more ‘free’ than the person who avoids ‘disreputable’ sexual behaviour. Satanic sex is not, as some imagine, an orgy of non-stop promiscuity so much as an orgy of whatever truly turns you on – even if that is total abstinence.

In the chapter on ‘Satanic Sex’ in The Satanic Bible, LaVey wrote, ‘Satanism condones any type of sexual activity which properly satisfies your individual desires – be it heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or even asexual, if you choose. Satanism also sanctions any fetish or deviation which will enhance your sex-life, so long as it involves no one who does not wish to be involved.

‘The prevalence of deviant and/or fetishistic behaviour in our society would stagger the imagination of the sexually naïve. There are more sexual variants than the enlightened individual can perceive: transvestism, sadism, masochism, urolagnia, exhibitionism – to name only a few of the more predominant. Everyone has some form of fetish, but because they are unaware of the preponderance of fetishistic activity in our society, they feel they are depraved if they submit to their “unnatural” yearnings.’

While fetishism is a broad term, covering a wide range of different sexual proclivities and erotic obsessions, somehow sadomasochism and dominance/submission – the erotic exchange of power and pain between partners – seem to be the flagship of the deviant fleet. Perhaps this is because of the flamboyant paraphernalia of whips, chains and leather, or its uniting of the apparent opposites of pleasure and pain. Or perhaps, as Freud suggested, pain and pleasure are not incompatible opposites but different sides of the same coin, with sadomasochism bringing us uncomfortably close to that truth.

Freud was not alone in reaching this uncomfortable conclusion. In his book Sexual Anomalies and Perversions, Magnus Hirschfeld recalled a particularly haunting experience that underlined the relationship, at least for some, between Eros and Thanatos. Hirschfeld was in Berlin in 1919 (at the dawn of the German decadent era), when, after a political uprising was bloodily suppressed, he was asked to accompany ‘a woman to the mortuary where, among hundreds of bodies, some of which were shockingly mutilated or had their throats slit, we discovered her son . . . In the identification hall an endless stream of people, mainly women, were filing past the unidentified bodies and an attendant who knew me called my attention to some girls who had for several days continually rejoined the queue, evidently because they could not tear themselves away from the sight of the male bodies which lay, entirely stripped, before them . . . The expression on their faces was similar to that which I had seen when the women of Madrid and Seville watch the bull-fighters in the ring.’

PHILOSOPHY IN THE BOUDOIR

A late-eighteenth-century engraving depicting one of the many orgies in the Marquis de Sade’s epics of sadism and sex.

The term ‘sadism’ is derived from an eighteenth-century French nobleman named Donatien Alphonse de Sade. It’s surprising, perhaps, that the Marquis de Sade, whose name has become synonymous with the ultimate cruelty, should have many admirers – but, since his death in 1814, his work has been enthusiastically applauded by Decadent writers, surrealist artists, and even some feminists. A nobly born, squat-figured cavalry officer, de Sade was distinguished by a lively mind and an even livelier sex drive. His kinky tastes ran to whipping and being whipped, and erotic games with hot wax, as well as both heterosexual and homosexual sex (which still carried the penalty of death under French law at this time). As an ardent atheist – some say Satanist – the Marquis also introduced blasphemy into some of his orgies, giving them the flavour of improvised Black Masses.

Because of his high birth, if de Sade had confined his adventures to lowly prostitutes and maintained a level of discretion, he could probably have pursued his unorthodox love life without legal interference. But, in 1763, he married into a respectable middle-class family. De Sade hoped to share their wealth in exchange for the prestige of his aristocratic name, but his scandalous reputation made him a public embarrassment to his new in-laws. In exasperation, de Sade’s mother-in-law arranged to have her unrepentantly deviant relative imprisoned in 1777, and he was to spend most of the rest of his life in gaols and lunatic asylums. It was here that de Sade was to write the stories that made him notorious. Meticulously, secretively, by candlelight, the Marquis de Sade wrote pornographic epics detailing acts of sexual cruelty and perversity that easily eclipsed anything he ever attempted in real life.

Indeed, many of his modern champions claim that, while he may have had unusual sexual tastes, de Sade was not by nature a cruel man. The prostitutes he hired consented to be whipped, and when fate, in the shape of the French Revolution, put the life of his mother-in-law into his hands, ‘Citizen Sade’ spared the woman who had been responsible for so much of his own misery. But de Sade placed no fetters on his imagination, allowing it to roam freely through his darkest sadomasochistic fantasies. However, it is the philosophy woven into his pornographic stories that has most intrigued his posthumous admirers.

The Marquis de Sade’s religious philosophy displays an atheistic attitude so militant it borders upon Satanism. His observation that the universe is actively cruel and unjust is best expressed in the twin novels Justine and Juliette, about two sisters – one of whom is virtuous and suffers terribly for it, the other who is wicked and prospers because of it. The books are subtitled The Misfortunes of Virtue and The Prosperity of Vice: the same idea reflected in Anton LaVey’s maxim, ‘No good deed goes unpunished.’

De Sade’s ideas on law and society reflect a similar attitude. He reasoned that we should follow our natural inclinations rather than the dictates of an imaginary god, and if we felt natural urges towards sex or violence then it was more sinful to suppress such urges than to express them. Whether he every truly believed this, or whether it was just a symptom of his deep frustration at being imprisoned for so long, is difficult to say. But the Marquis de Sade’s perverse philosophy of total freedom has excited, outraged and inspired people long after his small-minded oppressors have been all but forgotten. Like every challenging philosophy, this has its distinctly dark side: while several modern commentators see de Sade as a radical advocate of personal liberty, a few criminals have used his writings as philosophical justification for their crimes. The most obvious example is the British serial killer Ian Brady, a devotee of the notorious Marquis, who, with his partner Myra Hindley, committed a murderous series of sexual atrocities against children in the 1960s.

Hirschfeld later notes that the Marquis de Sade had witnessed women surreptitiously masturbating at public executions, which were noted as good pick-up locations by young men. Classical literature also records that the Roman empresses Messalina and Theodora masturbated while watching gladiatorial combat.

While Freud used sex to map out the human mind, and Crowley employed it to chart the mystical world, LaVey regarded sex as an allegorical guide to human society. In his biography, The Secret Life of a Satanist, the chapter dedicated to ‘Masochistic America’ suggests that the Black Pope’s experiments in sadomasochistic ritual and psychodrama in the 1960s could profitably be applied wholesale to the present-day USA.

LaVey diagnoses the major problem of Western society as an epidemic of unrecognised masochism. Overt masochism is harmless, admirable even, as an honest expression of an individual’s identity. But the repressed masochism brought about by the confused messages broadcast from TV set or church pulpit – which simultaneously tell the masses they’re all worthy individuals while reminding them of their inadequacies – just create self-important zombies with a subconscious desire to be punished. And all too often, such covert masochism manifests itself as attempts to provoke better-developed or more powerful individuals into punishing them. By this typically perverse line of argument, LaVey presents the thugs and hooligans used to justify repressive laws of Church and State as malfunctioning masochists created by those very same institutions. ‘Most people don’t want to pick a leader,’ says LaVey, ‘they want to pick an executioner. So when they “elect a leader” they’re really saying “I want you to pull the switch, not the other one.”

In 1998, the year following his death, a requiem was held for Anton LaVey at London’s Torture Garden in recognition of his role in promoting an understanding of fetishism. The club’s name is derived from a 1899 book by Octave Mirbeau. One of the most macabre Decadent novels, The Torture Garden describes an elegantly depraved Englishwoman introducing a cynical Frenchman to the immoral delights of a Chinese garden where torture is practised as an art form. Brutal sadism and unspeakable beauty become inextricably intertwined like two poisonous vines, in this novel which Oscar Wilde referred to as ‘a green adder of a book’.

The Torture Garden is just one of dozens of popular fetish clubs operating in most Western cities today, high-profile concerns open to anyone willing to pay the entrance fee and wear the appropriate fetishistic costume. Such clubs would have been unthinkable thirty years ago, at the time of the foundation of the Church of Satan. By 1990 the unimaginable had started to happen, and S/M nightclubs – once a secretive domain confined to the red light districts of Europe’s most liberal cities – started to surface above ground. So where did these popular fetishist night-spots emerge from, and why do so many fashionable young people attend?

It isn’t that such clubs didn’t use to exist – but they were private, discreet affairs, part of an erotic underworld where wealthy deviants rubbed shoulders with petty criminals, prostitutes and maverick artists. It was an underworld that the Decadents of the 1890s had been very familiar with. Just as in the 1990s, when Marilyn Manson, the band, summoned up the most exotically grotesque ‘sex workers’ they could find to liven up their recording sessions, so poets like Baudelaire and the flagellant masochist Algernon Swinburne were familiar faces in the flesh pots of the 1890s. In the erotic underworld of the bath-house and brothel, the contrast between the beauty of carnal love and the sordid nature of forbidden vice proved irresistible.

Oscar Wilde described his own predilection for hunting down young rent boys in London’s dingy backstreets in typically decadent prose: ‘It was like feasting with panthers. The danger was half the excitement. I used to feel as the snake-charmer must feel when he lures the cobra to stir from the painted cloth or reed-basket that holds it, and makes it spread its hood at his bidding, to sway to and fro in the air as a plant sways restlessly in a stream. They were to me the brightest of gilded snakes. Their poison was part of their perfection.’

Gen, lead-singer with radical fetish rockers the Genitorturers.

Gen of the Genitorturers: born of the same Florida underground that spawned Marilyn Manson.

A century later, when Marilyn Manson frequented a New York S/M-themed restaurant named La Nouvelle Justine (after the De Sade novel Justine), there may have been less of a sense of ‘feasting with panthers’. All the same, greater and greater extremes have been introduced into the public arena in order to recapture the thrill. At London’s Torture Garden, members pin their lips together with needles, hang from the ceiling with catheters applied to their genitals and grind at their own metal-clad crotches with industrial power tools. In fact, these exotic scenes can be perused in two fully-illustrated coffee-table books on the Torture Garden, available from most good bookshops. Interested spectators can also subscribe to the glossy, prestigious fetish publication Skin Two, or watch an art-house movie extolling the virtues of the fetish scene, like Preaching to the Perverted.

In short, fetishism – if not wholly respectable – is not the illicit activity it was one hundred, thirty or even ten years ago. Tattoos, nipple rings and other body-modifications, once the self-inflicted mark of the outsider and outlaw, are now mere fashion statements. Even the most outrageous scenes – like the Torture Garden – are struggling to retain their cutting edge against a tide of fashionable, mainstream acceptance. In several ways this is a good thing – Oscar Wilde was ultimately gaoled for ‘feasting with panthers’, and renounced his decadent past. On the other hand, it renders the whole business rather toothless. Robbed of its element of danger and taboo, the sexual underworld is in danger of becoming a sterile place where fake fetishism is merchandised for another generation of conformist consumers. So how did we get to this position, and will such tolerance become ultimately tedious?

In the 1980s, the increasing danger posed by AIDS began to make the idea of unorthodox sexual practices like fetishism more attractive. Added to all this, fetishism was becoming ‘sexier’ as it became trendier. During the first half of this century, it had a real image problem: it was the province of pin-striped perverts, a vice for fat, balding bank managers and bored, middle-aged suburban couples. To outsiders it appeared simultaneously sleazy and sad. The women seen wielding the whips in Skin Two, however, are sexy young dominatrices, while the scene now boasts a daring and vitality many hip celebrities are happy to be associated with. It’s become slick and sexy, but, inevitably, has started to lose its dangerous edge in the process.

This transformation owes a lot to both rock’n’roll and youth counterculture. In the same way that entertainers gradually made homosexuality acceptable in the late twentieth century, and glam culture helped make camp chic, youth culture has made studs and leather cool. Tattoos were previously rites of passage in macho blue-collar worlds like prisons and army barracks – through the biker subculture they became marks of defiance for rebellious youth. (Rockers were more likely than hippies to see the inside of a prison cell, and the biker cult was largely born of ex-servicemen – the Hell’s Angels were originally a US Air Force squadron.) Black leather, for so long the fabric of choice in the fetish community, became the uniform for a generation of teenage rebels. Punk, with its hunger for shock, brought crude piercing and outrageous bondage gear out of the closet and onto the high street.

But all of this was window-dressing, fetish icons taken out of context for effect. Authentic fetishism didn’t become hip until the 1990s, after the 1989 publication of the Re/Search book Modern Primitives. Still a startling publication today, Modern Primitives documents in frank interviews and eye-wateringly graphic photographs the excesses explored by the most daring pioneers of the sexual underworld.

The book soon became a well-thumbed artefact in both penthouse and squat, one of the most shocking items in the counterculture library of the 1990s. Prophetically, Modern Primitives recounts a recorded discussion between Anton LaVey, Blanche Barton, Temple ov Psychic Youth founder Genesis P-Orridge and editor V. Vale. P-Orridge wonders if ‘this Modern Primitives book is just going to encourage people to emulate and mimic . . . like people becoming junkies to emulate William Burroughs, or people going to prison to emulate Jean Genet?’

The editor responds that it’s okay if it does, because he sees the movement as ‘a statement against Christianity’ – appropriately enough, as the idea of sadomasochism and body-modification as a gateway to spirituality had already become a central doctrine of the modern primitive movement. The book opens with a long interview with Fakir Musafar: an American advertising executive whose spare time is occupied by extreme sadomasochistic rituals, deliberately modelled on the ceremonial practices of primitive tribes who use pain to achieve altered states of consciousness. The idea of a return to exotic, pre-Christian practices that horrify straight society was appealing to the readers of Modern Primitives. Thus, the 1990s counterculture would adopt S/M and scarification as a self-conscious spiritual or religious statement.

The idea of masochism as a spiritual practice is nothing new. Crowley had conceived of a faith with sadomasochistic sex as a sacrament, and, whatever V. Vale may believe about the anti-Christian nature of S/M, many have identified deep, unconscious sadomasochistic elements in Roman Catholic iconography. In fact, its imagery of ecstatic martyred saints has been interpreted by some as little more than holy porn – such as the image of Saint Sebastian, whose arrow-studded body has become a homo-erotic icon.

As identified by LaVey, the whole ethos of the Christian faith may be seen as masochistic when symbolised by the cross – the very object that its messiah was tortured to death upon. Aldous Huxley’s 1956 book Heaven and Hell speculates on the relationship between self-induced suffering and religious ecstasy, as in the case of the Christian ‘Desert Fathers’ – the prototype for the medieval monastic orders, who developed much of the Church’s early dogma while living uncomfortable, deprived lives of self-enforced exile in a hostile wasteland. Terence Sellers, in her classic manual of sadomasochistic etiquette, The Correct Sadist, observes that ‘sadomasochism enjoys all the forms of religious piety – kneeling, praying, worshipping, sacrifice, invoking and punishing’.

While the primitivism of the modern primitive movement concerned itself with the religious aspects of sadomasochism, its modern side assimilated new medical theories on the connections between pleasure and pain. The term ‘masochism’, like its counterpart ‘sadism’, was derived from a specific historical figure. Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, an Austrian, wrote his 1869 novel Venus in Furs to indulge his obsession with being punished, preferably whipped, by a dominant woman – particularly if she was dressed in furs. The purely fetishistic desires of Sacher-Masoch are emphasised by the fact that there is no conventional sex at all in his book, and the main characters remain clothed throughout.

BLOOD AND SPIRIT

One of the first truly unsettling photographs in Modern Primitives shows Fakir Musafar hanging from a tree by two hooks through his nipples, performing the Native American O-Kee-Pa ceremony. Better known as the Sun Dance, this extremely painful ritual was voluntarily undertaken by Sioux Indians who wished to receive divine visions, until the US government banned it in 1904. In the accompanying interview, Musafar quotes from an 1867 description of the original ritual: ‘An inch or more of flesh on each shoulder, or each breast, was taken up between the thumb and finger of the man who held the knife; and the knife, which had been hacked and notched to make it produce as much pain as possible, was forced through the flesh below the fingers, and was followed by a skewer which the other attendant forced through the wounds . . . There were then two cords lowered from the top of the lodge, which were fastened to these skewers, and they immediately began to haul him up . . . The fortitude with which every one of them bore this part of the torture surpassed credulity.’

Modern Primitives also contains an essay by Wes Christensen on the self-mutilation rites of Central American tribes like the Maya and Aztecs: ‘Unlike the regular penance of routine bloodletting, the self-mortification techniques required for the Maya Vision Quest were severe: the penis was cut or pierced with cords linked to other participants; the tongue was punctured and long cords or sticks “the size of a thumb” passed through the opening.’

Modern Primitives, and the subculture it promoted, focuses on exotic foreign rites, but connections between masochism and religion can be found much closer to home. In the second appendix to his 1956 study of religion Heaven and Hell, Aldous Huxley writes on the visionaries and mystics common to early Christianity: ‘ . . . most contemplatives worked systematically to modify their body chemistry, with a view to creating the internal conditions favourable to spiritual insight. When they were not starving themselves into low blood sugar and a vitamin deficiency, or beating themselves into intoxication . . . they were cultivating insomnia and praying for long periods in uncomfortable positions, in order to create the psycho-physical symptoms of stress.’ In other words, Christian holymen were just as prone to masochistic extremes as their more ‘primitive’ equivalents.

Over 120 years later, author Brenda Love expounded on ‘algophilia’ (pleasure from pain) in her Encyclopedia of Unusual Sex Practices, as something largely born of a physiological origin rather than a purely psychological fetish: ‘We detect somatic pain by stimulation of the free nerve endings that lie near the surface of the skin. Once activated they transmit a signal to the brain, however, this is not a guarantee that the sensation will be perceived as painful . . . a person’s mood affects this process and if he is anxious the pain will be sharper, whereas if he is sexually aroused, feels safe, in control, and submits to the partner, the sensation may even seem pleasant . . . Extroverts are thought to require stronger tactile and mental stimulation than introverts and will not register pain as quickly. Once pain has been registered for 20-40 minutes the body will begin to produce opiate-like chemicals to reduce pain sensations. People playing with pain normally desire to create enough to trigger the release of these chemicals with their anaesthetic, euphoric and trance-like qualities . . . Modern society views pain as an affliction and does everything possible to inhibit its effects. We may someday have a better understanding of its biochemical qualities and pain may prove to have more therapeutic value for our ability to recuperate from emotional trauma than we realise.’

If religious notions are the modern fetishist’s connection with the past, and the sexual psychology of pain their link to the present, then their key to the future lies in body-modification. Some modern primitives look forward to a time when we are no longer limited by the bodies we are born with and can alter them, via surgery or cybernetics, for aesthetic or pleasurable purposes. In this fetishistic utopia, the body becomes a canvas upon which we can explore limitless sexual and artistic possibilities, literally rebuilding ourselves to please ourselves. Bodily parts can be artificially decorated, enhanced, or even replaced like designer accessories. This attitude echoes (albeit darkly) in the Mechanical Animals that are the focus of Marilyn Manson’s third album, and harks back to the nineteenth-century Decadents who believed the artificial to be superior to the natural (as in Huysmans’ Against Nature).

It’s a short leap from the Decadent ideal of man modelling his environment to suit his own tastes to the concept of an individual modelling their own flesh to the same ends. In his book Moral Ruins, editor Brian Stableford observes, ‘If one can speak at all about a Decadent Ideal World . . . then the ideal world would be a world in which people had total control over all matters of biology, including their own anatomy, physiology and physical desires; it is an ideal which we can and ought to share, though far too few of us actually do.’

There has always been a heavily sexual element in rock’n’roll, even before the provocative wiggle in Elvis’s pelvis outraged conservative America in the 1950s. Indeed, the very term is derived from black slang for sex. The relationship between a performer and their audience obviously has sexual roots, and it’s difficult to describe the hysteria caused by popular bands among teenage girls as anything other than some strange emotional orgasm-by-proxy. Typically, Marilyn Manson have their own version of this sexual relationship between performer and audience, deliberately bringing its abusive aspects to the fore, and there are times when their tours seem more like travelling sadomasochistic orgies than roadshows.

Early Manson shows, which were in many ways provocative pieces of performance art, featured the frontman leading Nancy (later to form an abusive relationship with the singer) to the stage on a leash. He recalls the onstage relationship’s rapid descent into depravity, beginning with Nancy’s suggestion that he punch her in the face. The physical abuse became progressively crueller, to the point where Marilyn later speculated as to whether it may have caused ‘some brain damage because she began falling in love with me . . . Nancy and I began exploring sexuality as well as pain and dominance onstage.’

Success saw Marilyn Manson take their Theatre of Abuse from the intimacy of Florida clubs to larger venues. ‘There’s a real connection between the audience and us,’ Manson observes, ‘and it’s a powerful energy that can be directed in any form, whether it’s sexual or violent. It goes according to what people want.’ The sadomasochistic element is overt, from the exchanges of spitting to Marilyn’s self-mutilation and attacks upon other band members. ‘Everyone’s going to get something different out of it. At our shows, it seems, people don’t know whether to fuck each other or kill each other, and hopefully the same goes for listening to the record.’ And the religious overtones of his acts of self-mutilation are not unconscious. ‘It was a bit symbolic, on one level, because in front of an audience I see it as being ritualistic,’ says Manson, recognising the practice as ‘very old and powerful’.

Marilyn Manson bring this same sadomasochistic atmosphere to their backstage activities, where conventional rock’n’roll promiscuity gives way to more exotically dangerous indulgences. The Long Hard Road Out of Hell documents the sadomasochistic relationship between performer and fan pursued at a more intimate level. Under the influence of their irrepressible roadie Tony Wiggins, the band developed a routine that subjected hapless female fans to an experience somewhere between bondage sex, a religious confessional and a brutal session of psychotherapy.

The determination to bring this same sadomasochistic edge to Marilyn Manson’s records led the band to record one such session at the start of the Smells Like Children EP. The record label vetoed its inclusion, but Marilyn describes the episode vividly in his autobiography. The girl demanded humiliation and abuse, and Wiggins – his partner in debauchery – obliged. The girl’s pubic hair is cut off, she is whipped, and a chain wrapped ‘ominously around her neck’. It’s still not enough, and the session degenerates into a vortex of sadomasochism which climaxes with the girl screaming that’s she’s worthless, and wants to be killed. Even a veteran of degradation like Wiggins is shaken by this, and tries to make sure his victim’s okay – ‘she let loose a flurry of screams that no longer differentiated between pleasure and pain.“You know I’m not going to kill you,” he tried to soothe her. “I don’t fucking care,” she told him. “This feels so fucking good.”’

This same sadomasochistic ethos has been expressed throughout Marilyn Manson’s career. ‘You can’t make art without pain,’ their frontman opines. ‘Without sex, dope, confusion or whatever. You can’t grasp good music just out of air. You must do something for it. You must find yourself in your music. If not, it is just nothing.’

THE UNKINDEST CUT

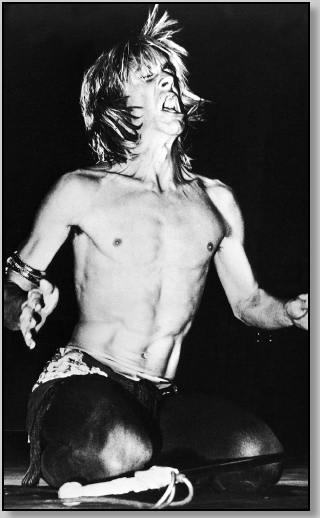

Self-mutilating wild-man Iggy Pop.

Perhaps the most unsettling aspects of Marilyn Manson’s stageshow – the parts that give even his most cynical critics pause for thought – are those moments when he cuts himself using broken bottles, or whatever else comes to hand. It became a regular feature during the band’s 1995 tour with Danzig, where the vocalist began in earnest to chart what he calls ‘the road map across my chest’. On the surface, self-mutilation seemed to reflect exhaustion and disillusionment caused by the strain of endless touring. Beneath that, as Marilyn confessed: ‘I was deep in the cavity of misery because Missi had called and said she wanted to end our relationship – the first relationship that meant anything to me’.

Marilyn Manson isn’t the first rock star to publicly carve his frustrations into his torso. Back in the early 1970s, Iggy Pop’s taunting of his audience turned self-destructively bloody as he got increasingly deeper into violent self-mutilation (also apparently originating from woman trouble, though drug abuse and general psychosis began to play their parts). This kind of extreme behaviour has a long and curious tradition in the entertainment world. Early twentieth-century American opera singer Geraldine Farrar once revealed to an interviewer that at every performance she cut herself open with a knife. According to Brenda Love in The Encyclopedia of Unusual Sexual Practices, ‘Cutting creates an intense moment and display of personal power over the person’s fate. The person’s cicatrix acts as a constant affirmation of their new found power over pain and tragedy.’

Nowhere is this more evident than on Antichrist Superstar, which he describes as akin to an occult ritual. Central to that ritual was the abuse and pain the band subjected themselves to during its recording, a series of ordeals close to the sacred masochism of the modern primitive subculture. ‘I would put myself through a lot of physical pain with drugs or masochistic behaviour,’ Marilyn recalls. ‘And that was something that transformed me, really. I find myself being a different person. Yet no therapy was involved. I’ve tried a couple of times, but I find that self-examination works better for me than trying to explain it to someone else’. Like the modern primitives, he discovered his personal spirituality in the altered states brought about by suffering and sleep-deprivation, but, like Anton LaVey, he identified the ‘satanic’ power of those states as lying somewhere between religion and psychiatry.

There is an unquestionable authenticity about Marilyn Manson’s fixation with the dark side of the libido. When he says, ‘To me, sex was ugly and still is – about fucking pigs and putting douche bags up your ass,’ you are inclined to believe this dedication to deviance is sincere (in spirit, if not in deed). If Sigmund Freud is to be believed, we must look to the experiences of the young Brian Warner for the origin of this attitude. In The Encyclopedia of Unusual Sexual Practices, Brenda Love has this to say on masochism:

‘The reason people feel a need to convey love in this manner often lies in their past environmental conditioning . . . In addition, these people probably only received nurturing from their parents when they were ill or injured, therefore, they may feel that the only time they are permitted to receive nurturing is when they are weak or injured. Similar conditioning is now considered a contributing factor for people who become sexually aroused by piercing and cutting . . . Masochism plays a role in creating a feeling of self empowerment or self esteem. The masochist faces fear, pain, or humiliation and not only survives but has an orgasm or receives love as a reward.’

In his autobiography, Marilyn describes a claustrophobic childhood relationship with his mother wherein she tried to maintain the bond by convincing her son he was more sickly than he actually was. Brian Warner’s early life is crowded with incidents where sex, pain, perversion and spirituality become hopelessly entangled. The pious teacher at the Christian Heritage School who most fills him with loathing also inspires lust, tormenting the young boy with a confused blend of hatred and longing. Picking the favourite article from his early journalistic career to reproduce in The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, he would choose ‘We Always Hurt the Ones We Love’. It was a feature about Mistress Barbara – a ‘short, corpulent’ dominatrix who ‘represents everything a woman is about while at the same time contradicting what we believe is normal behaviour’.

Sometimes, emotion cuts much deeper than any flesh wound inflicted by a dominatrix, as Marilyn soon learned. His autobiography records an unhappy relationship with a girl named Rachelle, whose betrayal inflicts emotional pain on him that makes Mistress Barbara’s activities look tame by comparison. (He cites this romantic trauma as central in his decision to emotionally distance himself from a world he regarded with increasing distrust.) Manson even describes his pivotal professional relationship with Trent Reznor in sadomasochistic terms, claiming it was like Miss Barbara’s Dungeon, ‘strewn with unforseeable peaks of pleasure and pain’.

Such frustrations would erupt in Marilyn Manson performances, which became notorious for the lead singer’s habit of cutting himself on stage. While touring with Danzig, Marilyn performed his first major act of public self-mutilation, inspired by the apathy and antipathy of the crowd. In a fit of rage, he seized a beer bottle, smashed it on the drum kit, then bellowed a challenge at the crowd, stunning them and the band into virtual silence. There were no takers, so Manson carved the bottle across his own chest, creating what he describes as ‘one of the deepest and biggest scars on the latticework that is my torso’. From thereon in, the gigs transformed from tour dates to confrontational exercises in drug-fuelled performance art, while ‘the road map across my chest began to expand with scars, bruises and welts. We had all become wretched, exhausted, empty containers . . .’

As Brenda Love observes of this kind of self-mutilation (which she calls cicatrization), ‘Cutting has always been a basis for emotional healing. Today many people in mental institutions, hospitals, and prisons engage in cutting as a form of self-mutilation. The reasons given for this kind of behaviour vary, but most feel it puts them back in touch with their bodies so they feel human again.’

At bottom, the primary origin of fetishism remains the expression of individuality – which is why the fetish counterculture finds its darkest high-profile advocate in Marilyn Manson, the self-appointed ‘Nineties voice of individuality’. Recalling the surreptitious childhood visit to his grandfather’s deviant den, in 1996 the newly-transformed Antichrist returned to his family home in Canton, Ohio, feeling drawn back to the cellar where the old man had kept all of his guilty sexual secrets. There Marilyn came face-to-face with what he himself had become.

The cellar is no longer a place of dread. On the contrary, it’s now the only place in his childhood hometown where he really feels secure. He even feels more in common with his grandfather than the young Brian Warner – like Grandfather Jack Marilyn Manson wears women’s lingerie, while his career of perversity makes the tawdry magazines and photos hidden in his grandfather’s dingy lair look tame by comparison. ‘My grandfather had been the ugliest, darkest, foulest, most depraved figure of my childhood, more beast than human, and I had grown up to be him, locked in the basement with my secrets as the rest of the family revelled in the petty and ordinary upstairs.’

If little Brian Warner, like his grandfather, had given way to dark appetites as he grew up, then at least they were his own appetites – not the sanitised demands of Church or TV. Rather than sacrificing your individuality, sometimes, perhaps, it’s better to be a deviant or a monster.