CHAPTER FOUR

Writing Roots

“I’m so much anticipating when I can afford to quit the regular lecturing circuit, which eats up time I’d far rather spend writing,” Alex Haley wrote to a Reader’s Digest editor at the end of 1973. “It’s not that the lectures are without regard, though: by now, I have spoken of this book to more than 1.5 million people in live audience, who are out there awaiting it.”1 Each day brought more mail from people eager to buy and read Roots, but Alex Haley still had to write the book.

Haley had established the basic story line for his family saga by the summer of 1969. He mailed the first chapter to his editor at Reader’s Digest and felt compelled to explain why a single chapter ran over two hundred pages. “I have not had it in me to leave out a single item that all the years of research turned up of what, truly, was the African culture of the mid-1700s,” Haley wrote. “You will see, clinically, the immense problem I faced. It could not be, all of this, in any way simply some rhetorical listing of items of that culture. That would be a book for students, scholars. People, by the many millions, need to know, almost by an osmosis, this culture.” Haley’s job, as he understood it, was “to weave [this] culture about the growing-up of the boy, Kunta Kinte. The chapter opens with his being born. It will end when he is a young man of about 16.”2 Haley later described the structure of Roots’s first section as echoing The Autobiography of Malcolm X. “I did not editorialize,” Haley said of the Malcolm X book, “but simply started with the subject as a child—as a fetus, actually—and related, in a very low-key way, successively, what happened to him, from childhood to adulthood. And I used that same technique with Kunta Kinte. It taught me to let the readers write their own editorial; I don’t do it for them.”3

Haley explained that the book’s vision of Kunta Kinte’s childhood as a free person was “the tree’s trunk.” Once readers identified with Kunta as a child, the horrors of his enslavement would be more vivid. “Everything that subsequently happens in the book derives at least part of its emotional power out of the reader’s knowing, for themselves, in an impact way, the delineated life and culture in which that infant, boy, young man Kunta Kinte grew up in Juffure Village, Gambia, West Africa,” Haley wrote. “Having grown up with this boy there, then when he goes into that stinking, fetid slaveship hold, in chains, in pains, the readers are going to experience that hold with him.” Haley had an abiding faith in the power of words to convey feelings, and he did not distinguish between the types of sentiments Roots might engender. Haley invited readers to empathize with Kunta as a child so that, chapters later, they would be more deeply traumatized by Kunta’s enslavement. “When on [Kunta’s] fourth escape his foot is cut in half (across the arch) for punishment, I am going to make a reader’s foot hurt,” Haley wrote. Haley said, “The foot-cutting is going to be three paragraphs I want no one ever to forget,” and he conducted specific research to make this scene of brutality come alive for readers. “I have been . . . to a physicist,” Haley wrote, “I have in cold abstract physics terms what happens when a six-foot man raises an axe with a three-foot handle and a four-pound head, and pulls it suddenly down toward a target—I have it in terms of foot-pounds, velocity, things like that . . . I have a surgeon’s cold, clinical description of every single successive thing that axe’s blade severs, epidermis through sole.” Haley concluded by promising, “I have worked, Tony. Ain’t nobody—nobody, nobody, nobody, who reads it going to be unaffected by this book.”4

Haley wrote and revised chapters of Roots regularly from 1967 to 1975. He preferred to start writing after dinner: “All the effort to massage a synthesis of my research into myself is planned for the late night moments when it flows out of me from as close to my subconscious as I can free myself to give.”5 Often, Haley would speak into a dictation machine from which a typist would later prepare a chapter draft. Haley liked to write and revise while he traveled, and he described working on planes “as if they were my office.”6 In handwritten jottings Haley marked time in the many months he worked on Roots:

July 20, 1969: Earlier this afternoon, man landed on the moon. Listened to broadcast in dining car of train California Zephyr.

August 20, 1973: Dad died this morning, 82. Finally he is back with mama, the wife he loved.

October 3, 1973: 5:15 a.m.—wow! Must get some sleep; must catch 8 a.m. flight to enter lecture tour.

October 4, 1973: Braniff #237 from St. Paul/Minneapolis to Kansas City. After lecture last night, slept 11 hours; needed! Feel great!!

August 11, 1975: Happy birthday to me! 54! Wow! Where’d those years go?7

Epochal events, personal moments, and quotidian details ran together amid the sea of manuscript pages that threatened to engulf him. Haley preferred goldenrod paper and green felt pens (which he described as his “two major fetishes”), and many of the thousands of archived pages of his drafts are so marked up that they practically bleed green ink.8 It took Haley a long time to finish Roots, but it was not for a lack of effort. He wrote, revised, and wrangled his prose for years to create his family history.

While it is clear that Roots is Haley’s story, it is equally clear that the book would not have been finished without the assistance of his friend and editor Murray Fisher, the pressure applied by Doubleday, or the financial incentive of the television deal with David Wolper and ABC. Haley had a vision for how “Kunta Kinte’s descendants [would] fall into the 260-year pageantry” of American history, but he needed help to turn this vision into Roots.9 “Murray Fisher had been my editor for years at Playboy magazine when I solicited his clinical expertise to help me structure this book from a seeming impassable maze of researched materials,” Haley wrote in the acknowledgments to Roots. “After we had established Roots’ pattern of chapters, next the story line was developed, which he then shepherded throughout. Finally, in the book’s pressurized completion phase, he even drafted some of Roots’ scenes, and his brilliant editing pen steadily tightened the book’s great length.”10 The six years of work between Haley and Fisher that preceded these three sentences were productive and at time contentious. This relationship between author and editor reveals a great deal about the pressure Haley faced as he wrote Roots.

Murray Fisher was twelve years younger than Haley and came to their relationship with more worldly experience. Fisher grew up in Asia—first in China, where his parents were American missionaries, and then in Tokyo, Japan, where his father was assigned for Reader’s Digest. Fisher worked as a war correspondent in South Korea and for NBC before being hired by Hugh Hefner at Playboy. At Playboy’s office in Chicago, Fisher developed and edited the monthly celebrity interview feature, which debuted in 1962 with Haley’s interview of Miles Davis. Fisher helped edit The Autobiography of Malcolm X and left Playboy in 1974 to work full time with Haley on finishing Roots.11 After working together closely for several years, Haley told Fisher that their relationship was evidence that “friendships can thrive between sharply diverse personalities.” “You’re brilliant, mercurial, cosmopolitan; you decide/act almost by reflex,” Haley said. “I’m really deeply of Henning: slower, methodic, pray nightly; innately I listen, observe, saying nothing until I can sufficiently playback, mull over, finally decide. This pattern, in fact, is why Roots exists—one decade of this pattern. . . . I despise any unnecessary confrontations—as I think most are; I’ve engaged in two angry, shouting confrontations, the last in 1947.”12

Haley and Fisher talked on the telephone about drafts of the book for a couple of hours nearly every day in 1970. Haley was living in San Francisco after divorcing his second wife, Julie, and it would be three years before he would see the couple’s young daughter, Cindy, again.13 “‘Before This Anger’ really now is happening,” Haley wrote to his agent Paul Reynolds at the end of the year. “My best writing happens in thrusts,” Haley told Reynolds, noting that he was “working about 18 hours each day, sleeping in short takes.” Haley tried to avoid distractions and accepted telephone calls from only a handful of people, such as Fisher. “When Murray has done his thing, editing, at which he is magnificent, sometimes he is enough overcome by the steadily building sheer overwhelming drama of the book being done now that he will telephone and read the last take of it over the phone,” Haley said.14

Fisher could be a harsh editor. He often returned drafts to Haley with barbed comments in the margins: “What the hell is this?”; “Enough of this already—blah, blah, blah”; “Pretty dull stuff”; “This is history not story”; and the writing workshop standard, “Show, don’t tell.”15 Haley considered Fisher a “brilliant editor at cutting and condensing,” and he responded remarkably well to these criticisms of his work.16 While Haley had a sizable ego, he also recognized, rightly, that he needed an editor to rein in his story. Left to his own devices, Haley gathered more and more research material and continuously revised his chapter drafts. The top of one draft includes Haley’s handwritten note: “A further rewrite not originally intended, but I began doodling, then it demanded eventually full rewrite.”17 Haley’s creative process required him to continually iterate, and this made an editor indispensable to the development of Roots.

Haley’s favorite place to write was at sea, and he frequently booked trips on freighters to work on his book. The summer of 1971 found Haley on a ship that sailed around Mexico, South America, and the Caribbean before returning to San Francisco.18 “I am working better than ever in any other locale,” Haley wrote to Reynolds as the ship pulled away from Buenos Aires. “Tomorrow I will write Chapter 31 . . . in which Kunta Kinte, 16, is captured. By Rio, ten days from now, I hope to have him across the Atlantic and in Colonial Annapolis. Then I am going to have about another 40 days, living and eating and sleeping with Kinte and his descendants across ante-bellum slavery, and the Civil War, Emancipation and my birth.” Haley was optimistic that the writing would go more quickly once Kunta had reached America. “It will go appreciably faster once Kinte is in the Colonial US—because then there is natural forward movement,” Haley wrote. “It has been agonizingly hard to create movement, steadily, in the static situation of 31 chapters whose primary purpose is to instill deeply into readers an awareness of what was African culture. But I know I have done it. No one ever will read this book and again think of a no-culture Africa.”19 Haley also reminded Reynolds that he intended to be one of his most successful clients. “The next time you chance to be talking to Irving Wallace,” Haley said, referring to the best-selling novelist, “mention to him that I said you cannot go into a South America bookstore without his titles all over! The guy’s sales must be utterly incredible! (Although I am going to show him something, with ‘Before This Anger,’ to be sure!)”20

Haley’s desire to introduce readers to African culture led him to gather pages and pages of research notes. “I’ve invested so much time and work collecting all of the items I have of the 1750s-1760s authentic Mandinka (Mandingo) village culture, from which Kunta was taken (and, symbolically, all slaves)—that at this stage, I want every item woven into the rough manuscript, so that culling necessary can be done from that total material. . . . I feel it momentously important,” Haley wrote. “One, this is, genuinely, Black History which is being so-clamored for. Lecturing across this country, North, East, South, West, sharing with audiences, mixed black-and-white, really only bits and pieces of what is to be in the book, I have witnessed emotional responses actually often to the point of tears (including my own). So that’s another reason I’m including here even the unused-as-yet, for you to appraise for potential weaving-in: the book is pre-tested in its effect.”21 Haley sent Fisher fifty single-spaced pages of notes on topics ranging from Gambian folktales and traditional fishing methods to kingdoms in Mali and the practices of Nigerian elephant hunters.22 In one of his notebooks, Haley wrote that he wanted the book to have “enough details to make the story live and real—but not a history lesson (i.e., don’t know how many pounds of beeswax).”23 Haley’s research impulses ran toward the collecting of minute details as though he needed to gather pages of historical facts to balance the fictional parts of his story. Haley later told Reynolds, “Sometimes, even I can’t understand why had it taken so long [to finish Roots]. I mean apart from all of the lecturing, and so forth. I think that I did the thing called ‘over-researching,’ in fact I know I did, for I find myself not using whole blocks of this or that which took weeks, or even months to get into my notebooks.”24 Fashioning this material into a narrative quickly grew unwieldy, which is one of the reasons Fisher took on such an important role as an editor.

Fisher came to play such an crucial role in developing Roots that Haley gave him 10 percent of the book’s literary rights and 5 percent of the motion picture rights. Haley wrote to Reynolds in the spring of 1973, asking him to draw up the paperwork. “My reason for this derives from the special mammoth nature of ROOTS, and the fact that Murray is investing, as my friend, a really singular job of editing which will contribute much to ROOTS’ success, which will be also singular,” Haley explained. Haley said that he valued the “intensiveness, expertness and otherwise overall caliber of editing of ROOTS that Murray Fisher is doing” and felt this work was worthy of significant monetary compensation.25 Haley’s agreement with Fisher was also motivated by Haley’s recognition that Roots overwhelmed him. “I’ll never again work as hard as this, at least for as long as this, on another book,” Haley told Reynolds. “I feel as if I’m climbing up a waterfall. It is really like writing four books.”26

Money problems continued to trail Haley, making it more difficult to complete his epic book. The IRS put a tax lien on Haley’s bank account in the summer of 1973, and at times Haley could not afford the xeroxing fees to send copies of drafts to Fisher, Reader’s Digest, or Doubleday.27 “You surely know that I’m so characteristic of so many of my craft, who have no ability in properly managing their finances,” Haley wrote to Reynolds. “Indeed, that’s a good part of why ‘Roots’ isn’t in bookstores now; for lack of proper managing otherwise, my chief income is from lecturing, which although it pays well still has eaten up all kinds of time that should have been spent with my typewriter and editing pen.”28 Haley’s busy and lucrative lecture schedule proved to be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, lectures brought Haley much-needed money and built a robust advance audience for Roots. On the other hand, every day Haley traveled to deliver a lecture was a day he was not writing his book. “I have got to become able to quit lecturing until after ‘Roots’ is delivered,” Haley concluded.29

Haley’s financial problems were compounded in August 1973 when his ex-wife Julie was committed to a psychiatric hospital for severe depression. Haley was in Negril, Jamaica, when he received the news. “Of course I’m sorry for Julie, who had dropped her insurance,” Haley wrote to Reynolds, before reflecting on what this meant for his daughter. “Immediately my problem is Cindy, without a functional mother. [Julie’s mother] says someone can be hired fulltime, or she herself will quit work if I can reimburse. My child support’s not quite half enough to handle all this.”30 Haley wrote to Lisa Drew at Doubleday to ask for a $10,000 advance to cover these unexpected expenses. Reynolds told Haley not to be too optimistic on this front. “Remember, they signed a contract for this book in Aug. 1964,” Reynolds reminded him. “I don’t think they’re going to write out a check for $10,000 now.” The solution, Reynolds argued in his familiar refrain, was to finish the book. “Of course you must try to help Julie and Cindy, but Cindy will not starve if you can’t help her and finishing Roots will mean that you can help her in the future,” Reynolds wrote.

If you help her now and as a result cannot finish Roots, you will be incapable of helping her six months or a year from now when she’ll need your help just as much. Your whole career so depends on your finishing Roots. . . . As far as I can predict, Roots should solve your financial problems. Nothing else that I know of will. What I’m trying to say is that I think you’ll be doing more for Cindy and Julie for the long pull by finishing Roots and not helping them than you will by not finishing Roots because of immediate help to them.31

The failures of Haley’s first two marriages and his shortcomings as a father did not make him unique among celebrities and career-oriented men of his generation, but they are noteworthy since he wrote the most famous family chronicle in American history. This is less paradoxical than it may seem. Haley described his search for roots as a detective story, and the project, with international travel and regular speaking engagements, suited his wanderlust and fulfilled his need to meet and woo new people. Roots allowed Haley to engage with the idea of family on his terms in a way that day-to-day life as a husband and father did not.

Haley took Reynolds’s coldly pragmatic financial advice and rededicated himself in the fall of 1973 to finishing Roots. Haley said that he recognized that “the biggest negative presently in my career is that my years of delay with ROOTS understandably has [sic] lowered my credibility among publishers.”32 Still, Haley sent Reynolds an ambitious three-year work schedule in which he planned to finish not only Roots but also a how-to book on black genealogy and a book on the Great Migration titled Booker. He expected to cap off this remarkable stretch of productivity with the film version of Roots coming out during the bicentennial in 1976. “It is almost as if Roots was written for that timing, through we know it wasn’t,” Haley said.33 By this time Haley projected that Roots would be over sixteen hundred pages, and Fisher was busy cutting and condensing Haley’s drafts.34 With every passing month, Haley’s optimism about finishing Roots seemed increasingly unwarranted. The book that had established him as a writer, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, was almost a decade old. He had missed dozens of book deadlines. And the racial tensions of the 1960s that had inspired Haley’s desire to move “beyond this anger” were no longer front-page news.

When Reader’s Digest published the first excerpt from Roots in 1974, no one was happier than Haley. “I am having the good, warm feeling of being vindicated,” Haley wrote upon hearing that his Digest editor liked the piece. “As you know, literally for years I have been dropping notes, saying I’m in this or that process with the book, until I know that it was starting to sound almost mythical.”35 While Haley’s story of his search for roots had already circulated widely via lectures, television talk show appearances, and articles in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and other newspapers and magazines, the Reader’s Digest piece was the first time readers saw the narrative of Kunta Kinte that Haley had written and Fisher had polished. In Reader’s Digest Haley found a perfect venue to launch Roots. Haley had published his first national magazine article in Reader’s Digest in 1954, he had spoken several times at the Digest-affiliated World Press Institute in St. Paul, Minnesota, and the magazine had supported Haley’s family history project since 1966, providing much-needed travel and research funds. Each month the magazine delivered accessible, interesting, and educational stories to a hundred million readers across thirty countries. Reader’s Digest’s goal was to bring culture to mass audiences, which was also what Haley hoped to achieve with Roots. Haley’s description of what he hoped to accomplish through his writing could have been the mission statement for Reader’s Digest. “I want and hope merely to try and write what I do in such a way that it will evoke such response as comes from the great bulk of my readers, ‘I had not realized _____,’ ‘I didn’t know _____,’ ‘I feel that I better understand _____’ and so forth,” Haley wrote in 1974. “Stated another way, if I can be a cause of an increased genuine awareness, and understanding, among we collective creatures of The Maker here upon this earth, then I will be happy.”36

Millions of people read Haley’s Roots preview in Reader’s Digest, and thousands wrote to tell him how much the work moved them. “As I finished tears streaked down my face,” a woman from Columbus, Ohio, wrote. “I found your [two-part condensed] book the most touching truthful work of our heritage. Thank you for this. I hope to someday see this as a permanent part of Black History in our public school system.”37 A public school official from New York told Haley that his efforts to make readers feel as though they were part of the story were successful. “I was alongside of Kunta from Juffure to Virginia,” she wrote. “Roots was the best thing I have ever read in my whole entire life.”38 A Philadelphia Daily News editor told Haley, “The joy of seeing it in Reader’s Digest is that it will reach its largest audience. Largest, that is, until TV does it. That will be The Event.” This editor also told Haley that he liked the book’s blend of fact and fiction. “Roots is one of the great mystery novels of our time,” he wrote. “Don’t let it get Dewey-Decimal-ed into sociology!”39 Haley was thrilled at the outpouring of admiration for the condensed version of Roots. “One of the most meaningful things for me is that it’s seeming to have quite as much intrigue for whites as for blacks,” he wrote. “The whites predominantly writing that Roots evokes in them the want to know more of whence they came. It reinforces my feeling that what Roots actually does is present the black facet of the humankind saga.”40

Producers David Wolper and Stan Margulies had the most important responses to the Reader’s Digest article. Originally from New York City, Wolper had studied film and journalism at the University of Southern California and had cofounded a television distribution company in his early twenties. By the early 1960s he had established Wolper Productions, which developed and sold dozens of documentaries to the broadcast networks. Stan Margulies, who joined Wolper Productions in 1968, recalled that he and Wolper had sold ABC in 1972 on two shows about generations of family. One focused on Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest, while the other focused on four generations of police officers. Neither show was produced, but Wolper and Margulies remained interested in the idea of bringing generational stories to television.41 They found the story they were looking for in Roots. “In the current (May) issue of Reader’s Digest there is an excerpt from a forthcoming book, Roots, by Alex Haley,” Wolper wrote to Margulies. “He is an American Negro who painstakingly traces his family back to its original roots in Africa. Using stories handed down in his family, plus his education and historical museums and associations, he manages finally to locate the actual African village where his family began. It is an incredible mystery-suspense tale, spanning three continents and seven generations.”42 Actress and civil rights activist Ruby Dee had told Wolper about Haley’s story in 1972, but at the time Columbia Pictures had an option on the film rights. By 1974, however, the book still had not been published, so Columbia elected not to extend their option.43 Wolper told Margulies that he expected Roots to be “next season’s biggest and most prestigious project” and said they should make an offer for the rights.

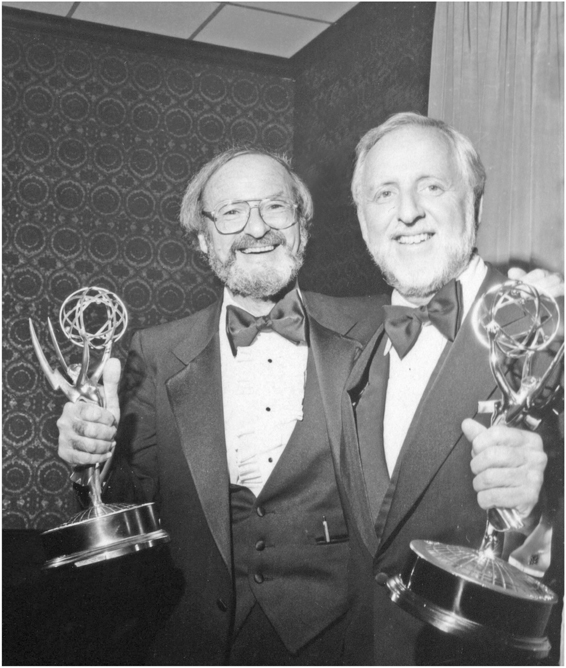

Figure 7. Stan Margulies and David Wolper celebrate their Emmy win for Roots, 1977. Nate Cutler/Globe Photos Inc.

Haley’s agents, entertainment lawyer Lou Blau in Los Angeles and literary agent Paul Reynolds in New York, were also busy cultivating potential bidders for the film/television rights to Roots. “I suspect that across the next two months, as the Reader’s Digest condensation runs, we are going to collect some motpix/TV bids of great interest,” Haley wrote.44 Haley was also eager to capitalize on Roots’s marketing potential. “Unlike most motion picture properties, this one involves two valuable subsidiary aspects that we should . . . participate in to a major degree,” Haley wrote. “Very valuable will be the academic markets for any documentary film of My Search for Roots, as evidenced by the perennial heavy demand for my merely lecturing about it. And anticible is a coming market for ‘Roots’ or ‘Kinte’ oriented products, such as sweatshirts, jigsaw puzzles of African villages, sundry models of applicable things.”45 While some critics blamed the television production for commercializing Roots, it is important to acknowledge that Haley was always eager for his work to achieve its full commercial potential. The success of the Reader’s Digest preview made Haley more ambitious about the promotional possibilities. Haley initially planned to follow Reynolds’s advice to wait until Roots was finished to sell the film/TV rights, when there would be “a very maximum seller’s market.”46 Lou Blau, however, was eager to make a deal. With producer David Merrick and Warner Brothers studio also showing interest in Roots, Blau negotiated a deal with Wolper.47 Wolper paid Haley $50,000 for the film/television option to Roots, with another $200,000 promised when Haley finished the book. The payment went to the Kinte Corporation, a tax shelter Haley set up on advice of Lou Blau.48 In Haley’s decade of work before finishing Roots, Doubleday paid him $77,000.49 These payments went toward Haley’s tax debts and child support obligations, and Haley always felt as if Doubleday did not value the epic book he was writing. The deal with Wolper was the windfall Haley had hoped to achieve with his project from the outset. While Haley had missed dozens of deadlines with his publisher, the television deal gave him the financial incentive and pressure he needed to finish writing Roots.

Like his previous pitches to Doubleday and Reader’s Digest, Haley’s spoken presentation of Roots over lunch at the Beverley Hills Tennis Club wowed Wolper and Margulies. “What I didn’t know there but learned later was that what Alex did at lunch was basically to give us his university lecture, which is dynamite, but over a lunch table it is double-dynamite,” Margulies remembered. “We sat there and our mouths dropped open 14 feet and we told Alex on the basis of that we were interested.” Margulies and Wolper also persuaded Haley that television, rather than film, was the best medium for Roots. “Alex was interested in communicating with the greatest number of people and we said one night on television is the equivalent to ten years of a movie run,” Margulies said. “If you really want to reach America, it’s called television and at the end of the luncheon we had a feeling that Alex was for it.” Once they had the television rights to Roots, Wolper and Margulies sold the project to ABC by having Haley give his presentation to ABC executives in a private room at the Beverly Hills Hotel.50

The television deal gave Haley some much-needed cash, but it also meant he now had both Doubleday and Wolper/ABC waiting for him to finish Roots. Reynolds worried that Haley was spending too much time in Los Angeles talking with Wolper about the television production. “This is ‘Dr. Reynolds, the slave driver’ talking,” Reynolds wrote to Haley, referencing one of the white characters in Roots. “Delighted as I am with your deal with Wolper . . . unless Roots is completely finished you should not go back to California, you should not do a stroke of work for Wolper . . . regardless of the contract. The book is the vital thing. . . . With no book, your whole house of cards would fall to pieces.”51 Reynolds had reason to worry. As the head screenwriter Bill Blinn was starting a treatment of the first television episode of Roots in December 1974, Haley missed yet another deadline with Doubleday.52 “I completely understand their dubiousness where I’m concerned,” Haley told Reynolds regarding Doubleday. “Ten years is a long time for any book. (I wager that will be one of the chief things advertised.)”53

Lisa Drew, Haley’s editor at Doubleday, had not heard from Haley for weeks before the missed deadline and learned from a newspaper article that Wolper had made a deal with ABC to broadcast Roots.54 “Somebody has given me a clipping from the Durham, North Carolina Morning Herald which says that Alex Haley’s ROOTS is being developed as a film for ABC,” Drew wrote to Reynolds. “Is this correct? If so, could you please give me an idea as to when they plan to use it on television? Do you have any further word on when the rest of the book is coming in to me?”55 Working on opposite coasts, Drew and Margulies talked regularly on the telephone trying to stay abreast of Haley’s progress. Drew recalled that “Stan would call me up and say, ‘We’re up to the point where Tom has run off and done this and what happens next?’ and I’d say, ‘Why are you asking me? You guys are ahead of me.’”56 While the schedule of ABC’s production was not yet determined, it was clear to Drew and her colleagues at Doubleday that “it was going to be a big deal” and that “there was going to be extremely serious extended publicity of our publication.”57

ABC initially planned to air Roots in March 1976, and Wolper feared that Haley would not get his manuscript to Doubleday in time for the book to be published before the series broadcast.58 Screenwriters Bill Blinn and Ernest Kinoy had completed treatments of Roots episodes 2 and 3, but neither they nor Wolper knew how Haley’s story would conclude. “Alex, we are running out of time,” Lou Blau told Haley in August 1975. “David Wolper is most apprehensive that ABC might very well walk away from the project if they were aware of the fact that all of the material has not yet been submitted to Wolper. Wolper emphasized that what you have submitted so far is not enough for his purposes, and you must submit your complete manuscript. It would indeed be a tragedy if the ABC deal goes down the drain.”59 Haley, working in Jamaica at the time, replied that even with Fisher’s editing assistance, Roots was too much for him. “Right now, this room is so inundated with Roots, not to mention my head, that I feel I don’t know if I’m coming or going,” Haley told Blau. “I understand Wolper’s concern, Doubleday’s concern, I’m working to finish the utterfastest I know how, like about 19 hours spent between editing pen or at this machine since this time yesterday; and I have the Faith that we’ll see sundry records and precedents set when Roots gets out there next year.”60 Haley had written Reynolds and Stan Margulies days earlier, telling them that Lisa Drew and Murray Fisher had both joined him in Jamaica and that the place had been a “beehive of work” as the three worked to finish the book.61 “We’ve arrived at a kind of rough schedule where all work pretty much through the day,” Haley wrote. “After dinner, Lisa works until 10:30 or so, and Murray to midnight or one a.m. I sleep for awhile after dinner until Murray’s ready to turn in, when he wakes me, and I take the swing shift until day, in the quiet, working ahead of them.”62 Haley said that all three got along very well but that Fisher had asked Drew not to say anything about the hands-on role he was playing in the completion of Roots.63

Haley knew that if he did not finish Roots by November 1975 Wolper would choose not to exercise the option on the television rights. This would cost Haley $200,000 plus all of the exposure that a nationally broadcast series would bring to him and his book. The pressure of making this all-important deadline exposed simmering tensions in Haley’s relationship with Fisher. The two had worked so closely for so many years on Roots that Fisher began to feel possessive of the story. While Haley desperately needed an editor’s assistance, he bristled at Fisher’s domineering manner. Just before Reader’s Digest published the first excerpt from the book in 1974, Fisher called Reynolds and said he was furious that he had not seen the final version of the chapter before it went to the magazine.64 For his part, Haley was upset that Fisher had phoned Reynolds. “I do not want him calling you or anyone else involved in handling Roots,” Haley wrote. “That is not his role. I am the author. He is an invited editor. Murray is a good friend; he is a brilliant editor, I think. He possesses an aggressive, dominating type of personality, which I regard as fine for his own life, but don’t thrust it upon me! I feel so strongly about these overstepping-of-role tendencies of his that if I find that he continues to exhibit them, considering that it’s my book, my career, then I have quietly determined that he simply will never see the manuscript of the book’s latter half.”65 Later in the same letter, though, Haley told Reynolds he hoped to patch things up with Fisher and then “press him to catch up” on editing the drafts.

These tensions reemerged in September 1975 when Stan Margulies hosted a dinner with Haley, Fisher, and screenwriter Bill Blinn. As the dinner guests talked about the Roots project, Haley grew annoyed that Fisher repeatedly interrupted him to finish stories about characters and events in the book. Haley felt upstaged and retreated to a balcony to collect his thoughts. Back in Jamaica, Haley wrote Fisher a lengthy letter.

“I’m taking Roots from here in without your editing,” Haley told Fisher, promising that the editor would still receive the agreed-upon percentage of the book and television rights. “The arrangement I volunteered makes it clear how much I both respect and solicit expert editing,” Haley continued. “During our working month, cumulatively I came to feel that you all but personify intransigence, that you consider that once the manuscript’s in your hands, who dares intrude? The author who would long sustain a cooperativeness with that perspective inevitably sustains a subjective sense of being professionally reduced, diminished; of self-doubt; of dribbling out his pebbles of self-confidence as a writer. Murray, I hope you can understand that it was scary, for awhile after I returned here, to write, uncertain inside if what was on the pages was going to survive. I’m too fond of me for that, my friend!”66 Haley told Fisher he was angry that the editor had directed a typist to put “Edited by Murray Fisher” on the title page of an earlier manuscript draft. Haley said he considered this akin to giving Fisher “co-credit” for writing Roots. “That is absurd Murray,” Haley wrote. “For my friend to perform his technical expertise, in appreciation I volunteered a generosity that’s far as I know, without precedent in the authorship business.”67 Haley also worried that Fisher was telling too many people about their work together on Roots. “This information dropped, seeded, in enough places, it can become the sort of titillating tidbit that can outgrow weeds and outlast dye,” Haley wrote. “Gaining dimension as it goes, in time it’s heard in cocktail parties in Idaho ‘Look, I happen to know he didn’t really write it.’ . . . I have got to avert any occasion for any ‘secret’ attaching to Roots.”68

As Haley navigated his relationship with his editor and rushed to finish Roots before the television deadline, he was stalked, as always, by money problems. “In a nutshell, my money situation is I’ve next to no income until I finish the long, long book, which I contractually must by Nov 30,” Haley wrote explaining why he did not have $760 to pay for his Master Charge account. Haley told the assistant manager at San Francisco’s Crocker National Bank that his money woes would soon be over. “In the first half of December I’ll receive $200,000 as a first payment on the TV rights,” he wrote. “The first day after that first sum’s deposited I plan to spend writing checks.” Haley even had to apologize to Flying Finger Manuscript Service for failing to pay a bill for typing a draft of Roots.69 Haley was philosophical about his constant money trouble. The “irony was that as long as I kept on those incredible lecturing itineraries you know I used to keep, earning the $50–80,000 a year I did at times . . . I could never possibly find the time to finish my book,” Haley wrote. “Or put another way, I was solvent, I was ‘secure,’ but I could not remain that and gamble on myself on the BIG one, you know? There’s something metaphysical about that.”70

Haley also felt the accumulated pressure of a decade of missed deadlines. “All I know is that I feel ready to cry when now or then someone writes, or says, ‘Aren’t you finished yet?’” Haley wrote to sociologist and University of California Santa Cruz administrator Herman Blake.71 “I have written about 18 hours every day, seven days a week all the summer, finishing Roots which absorbs work like a sponge,” Haley wrote to another friend. “Now I have about five weeks left to make a deadline on whose making hangs publication in early August 1976, followed by a long television series (14 hours) to open in Sept. It is so pressured that I am sending increments to the film people, whose writers are doing scripts from that, as they get it.”72 Haley said he felt “like a steamroller was chasing” him.73

With the television deadline looming, Haley wrote to Fisher to mend fences. Haley started the letter at four in the morning; he had been up late working with an ear infection, fever, and sore throat. “I think that we have the very real potential to work together in achieving some of the most formidable literature that has come down the line; and of visual products that will rank with the best as well,” Haley wrote to Fisher.74 Haley told Fisher that he still needed him as an editor, “our new understanding being that simply I will follow you to make sure it feels right, is right, to me.”

Over a ranging five-page letter, Haley wrote openly about what it meant to him to achieve success as a black author and the slights he continued to face. “I have heard I suppose two or three hundred of us [black artists, scholars, and celebrities] testify that in countless ways we have perceived how the average white people tend to underestimate us; to see us and so often to deal with us in ways which like as not they are themselves unconscious, as of lesser capacities for thinking, for discerning,” Haley wrote. Haley had interviewed and socialized with enough black celebrities to know that success did not eliminate racism and could heighten jealousy and distrust. “What all of this has to do with you and me and Roots is that Roots aspires to be a very symbol of black people’s bidding via the immensely powerful route of literature to be taken into the mainstream of acceptance of groups of people on par with each other. . . . For a book to achieve this for a historically maligned group would amount to a very staggering human contribution.”75 Haley recognized that Roots was going to lead to an intense level of scrutiny of him. “It is clearly imperative that I be worthy to sustain that image,” Haley wrote. “I have got to be able to stand under the spotlight of the scrutiny that will come, first curiously, then as the book grows bigger, increasingly critically. . . . It doesn’t go on forever, this scrutiny of critical bent; if a period of it can be weathered without the object of it springing any serious leaks, then okay, then it relents, and all’s okay.”76

For Haley, he and Fisher had to make it clear that Roots was an authentically black book. Haley believed that black celebrities like Motown Records founder Berry Gordy and actor Sammy Davis Jr. were victims of “black rejection phenomena.” To cut down successful black people, Haley felt, the media “subtly discover and reveal that in fact they’re somehow the product of, or controlled by, or contained by, white people. That seems to satisfy white people that all’s well; among black people the nice hopeful hero is virtually dumped with infuriation, or with disdain.”77 Haley asked Fisher to help him navigate this danger. “You and I have both got to be fully aware of the potentials of threats to what’s at stake,” Haley advised. “By no means does this intend to suggest you’re obscured from sight. . . . I want your editor role to be known. My only concern now is the context in which we do this. . . . You present the writer who faced the staggering organizational and presentation problems, which you as a trained, fresh eye and editing brain sought to help . . . and we’re homefree.”78 Haley described having already been visited in Jamaica by a representative of a civil rights organization who pressed the author to demand more black writers and production staff on the television series. Haley brushed away these concerns. “It seems of little moment that I am black, that Roots projects to pioneer in its area for black interests at large,” Haley wrote. “I can hear now some shrill [critics], black, ‘didn’t you know any black editors?’ I can deal with that. The thing I cannot deal with is the slightest innuendo that I am a product, or controlled, or contained, or any variation of such, however untrue; the point is it cannot be let to start.”79

Haley was much less worried about the response of black critics to Roots or the lack of black screenwriters or directors on the television series than he was with meeting the deadline for Wolper. Haley told Fisher he looked forward to hosting him in Jamaica to make a final push to the deadline. He promised that My Lewis, a recent PhD graduate from Ohio State University who had sought out Haley as a mentor, would be on hand to type up the revised manuscript. Lewis, whom Haley described as “diminutive, black, cute, quiet, sensitive, [and] very, very sharp,” later became Haley’s third wife.80 “We have GOT to make this deadline,” Haley wrote as he wrapped up the letter at 5:30 a.m. “Wolper Inc., must have it, in time to read, as their option has to be lifted by November 30, which means money, the start of it. I do not think I mentioned previously that in the way the Good Lord works His wonders, the new TV format is that they’ll premiere it (after early August book publication) with a September night’s full prime-time three-hour show, to be followed by weekly one-hour shows. That ought to sell over a million books in hardcover, don’t you think?”81