CHAPTER SEVEN

Watching Roots

Roots started with a birthing mother’s cry. After months of promotion by ABC, millions of Americans tuned in to watch the opening night of the television adaptation of Alex Haley’s best-selling family story. The first thing television viewers heard and saw after the opening credits was Binta Kinte giving birth to a baby boy. Binta can be heard moaning from inside of a thatched hut in Savannah, Georgia, on a film set designed to stand in for eighteenth-century Gambia. Binta is squatting and holding onto the large wooden pole at the center of the dwelling. Binta, shown from the shoulders up, is assisted by two midwives, while her husband Omoro paces anxiously outside. An infant’s cry punctuates the birthing scene, and moments later the audience learns the baby’s name. Holding the baby up toward a star-filled sky, Omoro says, “Kunta Kinte, behold the only thing greater than yourself.”

Opening the series with this birthing scene was strategic. Part of the strategy was to foreground some of the series’ prominent actors. Cicely Tyson, who played Binta, was an award-winning actress and, along with Ed Asner, the most famous and highest-paid actor in the cast. (Tyson had enough clout to request and receive a credit for her hairdresser, Omar.) Maya Angelou, an actress and author well known for her autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), played one of the midwives, while Thalmus Rasulala, recognizable from blaxploitation films and various television roles, played Omoro. The scene was also was strategic because the producers hoped starting with a birth would help the series appeal to viewers across demographic lines. Haley described a similar motivation for starting his book with Kunta’s birth and childhood. “I hope,” Haley noted, the audience will be “intrigued with a disarming baby—for babies are universal.”1 While they wanted to start with a baby, the producers approached this scene cautiously. “The birth sequence should be beautiful, and we should be very careful of groans and seeing Binta squat to give birth,” Stan Margulies wrote to David Wolper. “It is not a question of being authentic—but simply that too graphic a depiction of a birth in the first few minutes of the show might destroy everything that is to come.”2 The televised birthing scene closely resembled the opening of Haley’s book. “Early in the spring of 1750, in the village of Juffure, four days upriver from the coast of The Gambia, West Africa, a manchild was born to Omoro and Binta Kinte,” Haley wrote to open Roots. “Forcing forth from Binta’s strong young body, he was as black as she was, flecked and slippery with Binta’s blood, and he was bawling. The two wrinkled midwives, old Nyo Boto and the baby’s Grandmother Yaisa, saw that it was a boy and laughed with joy.”3 David Greene, who directed the first episode of Roots, described the first page of Haley’s Roots as “poetry” and remembers thinking, “How can I live up to that?”4

Despite Greene’s concerns, the twelve-hour television series lived up to and productively transformed Haley’s Roots. The televised Roots made the events described in the book visible to millions of viewers and aligned the book’s characters with flesh-and-blood actors. While similar claims can be made for almost all screen adaptations, the stakes for Roots, as a popular history of slavery, were higher. Roots televised scenes of brutality, such as captured Africans being transported across the ocean on a slave ship, Kunta Kinte being whipped on the Waller plantation, and sexual violence against enslaved women. But Roots also broadcast scenes of caring among black families and enslaved people. Roots mixed the emotional pull of a melodrama, the seriousness and scope of a historical drama, and some of the violence, sex, and humor of an exploitation film. This combination of genre characteristics made some critics and viewers uneasy. Writing in Time, for example, Richard Schickel criticized Roots as “Middlebrow Mandingo,” referring to the 1975 film Mandingo, an antebellum melodrama that titillated viewers with interracial sex. Schickel compared Roots unfavorably to a BBC series, The Fight against Slavery (1975, syndicated in the United States on PBS in 1976–77), that he found to be a “more subtle and mature work.”5 David Wolper and ABC, however, proudly designed Roots as middlebrow entertainment to tell a story about slavery that would appeal to a large mass audience. This mass audience, Los Angeles Times critic Mary Beth Crain argued, was crucial to Roots’s place in US culture and to the series’ impact on the popular history of slavery. “The mass catharsis of ‘Roots,’” Crain suggested, “has at last formulated a weapon equal in power to Birth of a Nation.”6 For eight nights in the winter of 1977, Roots walked a tightrope, appealing to universal themes of family and resilience while asking television audiences to identify with the lives, emotions, and struggles of a host of free and enslaved black characters. Over a hundred million Americans (and, later, millions more globally) were enthralled, horrified, and entertained by what they saw.

Figure 14. Binta Kinte (Cicely Tyson) and midwife Nyo Boto (Maya Angelou) show baby Kunta to Omoro and viewers.

Figure 15. Omoro Kinte (Thalmus Rasulala) holds baby Kunta skyward.

The television adaptation of Roots differed from the book in several key respects. Most controversially, the television production gave white characters much larger roles than in Haley’s book. In Haley’s book, the white slave catchers and slave ship crew are called toubob, and a white character with a proper name does not appear until Kunta learns the name of “Massa William Waller” at the end of chapter 51, over two hundred pages into the book. (Haley’s archives include the draft of a chapter written from the perspective of Captain Davies, but the author decided it was not needed.)7 In contrast, after opening with Kunta Kinte’s birth in 1750 the television series jumps ahead fifteen years to a scene set in an Annapolis, Maryland, port where Captain Thomas Davies is preparing to sail the Lord Ligonier to the coast of the Gambia. The slave ship captain in Haley’s book was unnamed and was described only from Kunta’s perspective. The captain’s personal history, motivations, and emotions were irrelevant for Haley’s story. Ed Asner, famous for his role as Lou Grant on the Mary Tyler Moore Show, played Captain Davies in the televised version of Roots, and promotional material for the series featured Asner prominently. The Davies character, established by the screenwriters and embodied by Asner, was a religious man who was morally conflicted about taking part in his first slaving voyage. “The captain,” Asner said, “created the good German, the person who goes along with evil.”8 Asner’s Captain Davies looked virtuous in comparison to his first mate Mr. Slater, portrayed by Ralph Waite. Waite, also a familiar television star from his role as the father on The Waltons, played a veteran slave ship crew member who enjoyed brutalizing slaves.

Figure 16. Ed Asner received top billing in ABC’s promotion of Roots. Asner’s character, the slave ship captain Thomas Davies, played a much larger role in the television version of Roots than in Alex Haley’s book. ABC Photo Archives/Getty Images.

The first episode of Roots cuts between Kunta’s life as a young man in the Edenic village of Juffure and the Lord Ligonier steadily approaching the Gambian coast. Head screenwriter Bill Blinn said that he had struggled for months to figure out how to structure the opening episode of Roots. At one point, Blinn planned to start with the assassination of Malcolm X and feature Haley as a narrator. After deciding that Kunta Kinte needed to be the story’s focal point, Blinn looked for a way to build narrative tension and to get white characters on screen early. Blinn found inspiration in the form of a 1962 Kirk Douglas star vehicle called Lonely Are the Brave. Blinn recalled that Lonely Are the Brave opened with the characters played by Douglas and Carroll O’Conner on a collision course. “You know they’re going to meet,” Blinn said. “You don’t know why, you don’t know how, you don’t know what the connection is, but the storytelling has told us these two are gonna [connect].” This gave Blinn an idea for Roots. “Let’s just start with the captain of the slave ship getting this assignment,” Blinn said. “We could keep cutting back to that slave ship, and seeing what was going on with Ed Asner . . . Because we know that over the horizon there was trouble. Once we got that construction we had a very solid footing to start the picture.”9

While the series rushed to get Kunta out of Africa, Roots did not shy away from Kunta’s traumatic voyage to America in the hold of a slave ship. The Middle Passage scene in Roots was crucial to depicting the transition between freedom in Africa and slavery in the new world. Roots was a story about coming to America, but it was not an immigrant story. The horrors of the Middle Passage cannot be adequately represented in any medium, and before Roots the journey had been depicted rarely in films and never on television.

In a warehouse on the outskirts of Savannah, production designer Jan Scott and her team designed and built the set for the first televised representation of the Middle Passage. Scott navigated several technical challenges in creating a realistic cargo hold film set on dry land. Scott monitored the color value of the wood to ensure that the black actors could be lit properly. She measured the walkway between the racks to make it small enough to appear cramped but large enough to accommodate a film camera. And she rigged lights to swing above the cargo hold, creating the impression that the ship was rocking with the ocean’s waves. When Stan Margulies objected that the aisle planking looked too clean, Scott prepared a mixture of cornflakes, shredded wheat, and bran. She moistened the concoction, let it sit overnight, and applied it the next day so the floor of the set looked like it was covered in urine and feces. Scott recalled that director David Greene walked onto the set and “stood at the bow looking down the aisle and all of the sudden he started to cry. . . . So he liked the set. I’ve never had a director walk in on a set and cry before.”10

Figure 17. The Middle Passage scene in Roots was crucial to depicting the transition between freedom in Africa and slavery in the new world.

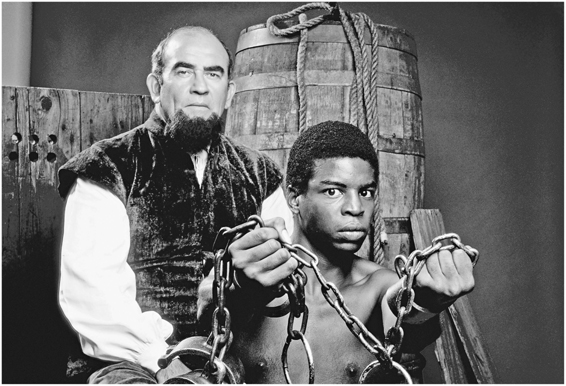

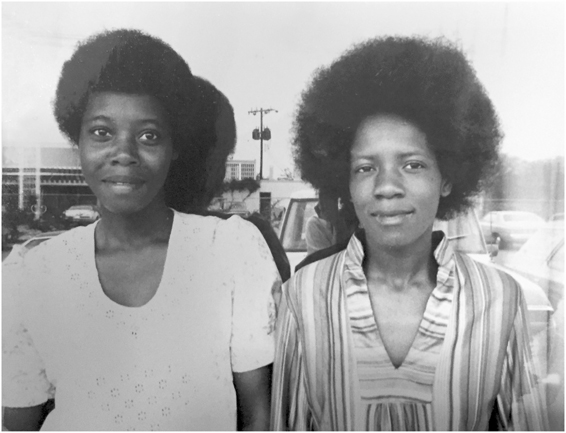

The human component of the Middle Passage scene was more complicated. LeVar Burton and Ji-Tu Cumbuka, who played a character called the Wrestler, were the only Hollywood actors in the cargo hold for the Middle Passage scene. All of the other enslaved characters were young black extras recruited from Savannah. The local casting consultants stopped young people at gas stations, shopping centers, and on their way to and from school. Each prospective extra was photographed and described on an index card in terms of sex, height, weight, and age (many were students from Savannah State University). The index cards also included a section where the casting consultants described the young people’s skin complexion in a variety of terms, such as “Negro,” “black,” “dark,” “pecan,” “mahogany,” “dark brown,” medium dark brown,” and “medium brown.” This array calls to mind artists like Nella Larsen who were keenly aware of the tremendous diversity of black people. “For the hundredth time she marveled at the gradations within this oppressed race of hers,” Larsen wrote of Helga Crane, the protagonist in her novel Quicksand (1928), watching a “swirling mass” of black dancers. “A dozen shades slid by. There was sooty black, shiny black, taupe, mahogany, bronze, copper, gold, orange, yellow, peach, ivory, pinky white, pastry white.”11 Larsen made it clear that these gradations of blackness told their own stories about history and genealogy, pointing to “Africa, Europe, perhaps with a pinch of Asia.” The casting consultants used language similar to Larsen’s, but their task was more narrowly defined. They were looking for extras to portray recently captured Africans, so the note “may be too light” meant the person was unlikely to be hired. This logic was in contrast to the preference Hollywood usually showed for light-skinned black actors.

The producers needed dozens of extras to fill the cargo hold set, and those that were selected were paid about thirty dollars a day.12 “I had the problem of teaching them to be actors, Africans, they had no idea,” director David Greene said. “I’m giving these young men a lecture about their history, then chained their ankles, then put oatmeal on their bodies.”13 Screenwriter Bill Blinn described being moved by the realism of the Middle Passage scene. “All of the stuff in the slave ship was as good as we could have imagined,” Blinn said. “The [film] dailies were difficult to watch, because the reality of being in that hold was horrific. . . . All of [the actors and extras] knew it was true. Between the lines I think most of them knew that someone with whom they had a blood relationship went through this dreadful, awful life. And that they owed it to them to portray it as well as they could.”14 In the Washington Post, Sander Vanocur singled out the Middle Passage scene in praising Roots. “The scenes on the ship, with the slaves chained together, stacked alongside one another, lying in their vomit and excrement, . . . are something we have never seen before,” Vanocur wrote. “We have read about slavery. But we have never seen it, never in such painstaking detail and never being experienced with such excruciating pain.” Vanocur described Roots as reintroducing a “sense of wonder” to television. “Television, when it sets out to portray reality, usually distorts it or just nibbles at it,” Vanocur argued. “I am at a loss for the proper word to use to describe what television has done with Alex Haley’s imagined reality. . . . All you know is that what you have seen leaves you with a terrible and transcending anguish.”15 Newsweek reviewer Harry Waters agreed: “The scenes in the hold, where 140 shackled slaves writhe in anguish, may be the most harrowing ever to enter our living rooms.”16 Many audience letters also pointed to this scene, including a viewer from Skokie, Illinois. “When I was fourteen years old and in the eighth grade, I learned about the history of the Black people,” he wrote. “All the text book reading in the world, though, could not have made the same impression on me as did scenes from Roots (e.g. the episodes which took place on the slave ship).”17

Figure 18. The local casting consultant for Roots looked for young black people around Savannah, like these two students from Savannah State University, to serve as extras during the Middle Passage scene.

While everyone agreed that the recreation of the slave ship’s voyage made for frighteningly realistic television, none of the Roots production team gave much thought to what shooting this scene would mean for the black performers involved. After lying on wooden planks for several hours, being shackled to the person next to them, and being covered with simulated vomit and excrement, most of the extras did not return for a second day of filming. Recreating the conditions by which their ancestors came to the United States was difficult and traumatic work, especially at an extra’s daily pay rate.

The case of Rebecca Bess is the most glaring example in this regard. Credited as “girl on ship,” Bess appears near the end of the first episode as an enslaved woman delivered to Captain Davies’s room as a “bellywarmer.” In the scene the sixteen-year-old Bess, who had never acted professionally, stares with terror at Asner’s character, her arms covering her bare breasts. While Captain Davies says he “does not approve of fornication,” it is implied that he rapes the young girl, signaling that this Christian character has too been debased by the slave trade. The next day (at the start of the second episode of the series), the young girl (still topless) climbs the rigging of the ship and jumps into the ocean to drown. In a series structured around the will of Haley’s ancestors to survive, Bess’s “girl on ship” stands out as the only character to choose death over the horrors of slavery.

Bess came to Roots via Eddie Smith, a local black stunt coordinator in Savannah. She received $187 for diving from the ship into the ocean, which she had to do twice because the camera failed on the first shot. Bess did not know how to swim, so the stunt coordinator gave her lessons in the pool at the Ramada Inn where the cast was staying. Director David Greene recalled that Bess was eager to earn the money to help her parents because her mother was in the hospital. “She was a very quiet girl and she did that dive,” Greene said. “Oh we had people in wet suits, we had crews on the ship to jump overboard and save her. We had a boat right off the end. . . . She touched all our hearts and there she was topless, climbing up on the rigging and jumping over and that was only one of many occasions when we stood there and looked and just saw history and knew that it had happened and it is just astonishing.” Greene described shooting the scenes with Bess as a “deeply moving experience.” “How do you think I felt when a genuine sixteen-year-old southern girl jumped off the rigging of that ship and committed suicide? You can hardly bear to watch it, and I could hardly bear to say ‘action.’”18 Greene’s slippage here between Bess (a “genuine sixteen-year-old southern girl”) and the historical character and incident she portrayed is revealing. Greene and the Roots production team wanted audiences to see this television drama in similarly realistic terms. Audiences described watching Roots as a physically and emotionally wrenching experience, but creating these realistic representations of slavery often came at the expense of black performers.

Rebecca Bess, for example, told a different and less celebratory story about her work on Roots. She filed a lawsuit against David Wolper in 1984, claiming that she had been promised a screen actors’ guild stunt contract. While it is not clear how Bess’s case was resolved, the terms in which she described her teenage role in Roots are telling. “During the filming I was required to go topless which I was not told I would have to do until we were on the set and getting ready to film,” Bess wrote. “I was required to drop my top approximately ten times. . . . I would be required to go topless once more as I would be taken to Ed Asner as a belly warmer by Ralph Waite. It would appear as though Ed Asner had sex with me that night and the next day I would run up on the deck trying to escape, climb up the mast, and jump overboard into the ocean. . . . During the filming I was required to jump off the ship twice. The reason being that during the first jump there was camera failure.”19 In all of the discussions among Roots producers and ABC’s Standards and Practices officials about how bare breasts could be shown on television, these white men never considered what it would mean for young black women to play these roles. For most of these performers, like Bess, Roots would be their first and only time appearing on television. While reviewers and audiences praised the harrowing realism of the slave ship scenes, the young black performers deserve much of the credit.

Even Burton, Roots’s breakout star, was overwhelmed with emotion during the filming of this Middle Passage scene. “I don’t remember very much [about the Middle Passage shooting] till this day,” Burton said later. “It’s as if I was transported. We shot that sequence in two or three days, and I have vague memories of the morning of day one. . . . I feel like I completely disappeared and something else came forward, someone else.”20 Burton described the Middle Passage shooting as “brutal.” “All of my ancestors, those people that I am spiritually and genetically connected to, came forward and really held me up during that day,” Burton said. “LeVar left and somebody else came in. . . . That’s how I survived it.”21 ABC’s official press release for Burton glossed this experience differently: “It’s a long and unlikely trip from the stately halls of the University of Southern California to the sadistic hell of a slaveship hold, but LeVar Burton, not yet out of his teens, made that trip for his role as Kunta Kinta.”22 For ABC Burton’s experience playing an enslaved person was promotional fodder, but for Burton and other black actors and extras it was an experience freighted with trauma and history.

Roots’s most iconic scene forced Burton to work through similar emotions. After Kunta Kinte arrives in Annapolis, Maryland, he is purchased by John Waller and transported to the Waller plantation in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. The plantation overseer, played by Vic Morrow, tasks Fiddler, played by Louis Gossett Jr., with teaching Kunta how to be a slave. Kunta refuses to accept this unfreedom or to answer to his assigned slave name, Toby. He runs away but is captured and returned to the plantation. In the climatic scene, the overseer commands a black man to whip Kunta, over and over again, in front of the other enslaved people. “When the master gives something, you take,” the overseer says. “He gave you a name. It’s a nice name. It’s Toby. And it’s going to be yours until the day you die. Now I know you understand me and I want to hear it.” Every time Kunta repeats his birth name he is whipped again. The beating continues until Kunta finally says, “My name is Toby.”23

“They were beating LeVar Burton and Kunta Kinte as one,” Burton later said of the scene.24 “I was really uncomfortable with the idea of being whipped,” Burton remembered. While makeup artists created the appearance of lacerations on his back, the whip was real. Burton had to stand, with his hands tied to scaffolding above his head, while a bullwhip struck him. On the first day of shooting the scene, Burton flinched every time the whipped cracked, so director John Erman postponed the scene for a couple of days. The young actor spent a day with the stunt expert who handled the bullwhip. Burton watched the stunt expert do tricks with the whip until Burton was comfortable that the expert could control the tip of the whip (traveling up to 120 miles an hour) so that it would wrap around the actor’s body without breaking the skin. The second shooting was successful, and Burton considered the scene one of the most powerful in the series. “Kunta was a warrior,” Burton said, “and he maintained that aspect of his identity throughout his entire life, he never surrendered who he was. . . . It was the indomitability of his human spirit, his warrior spirit, that prevented him from accepting that name, and that’s what that scene is about. I control who I am.”25

Figure 19. Kunta Kinte (LeVar Burton) is whipped until he accepts his slave name, “Toby.”

John Erman, who directed the episode, described it as a “devastating scene.” “The whole episode is about the fact that somebody is trying to break this young man’s spirit, and that’s what slavery was all about,” Erman said. Erman remembered that ABC sent the producers a note warning against scenes with whipping or blood. “The welts on the back is not the power of the scene,” Erman argued. “The power of the scene is what’s on that boy’s face and how he struggles to hold on to his identity and finally, finally, says, ‘My name is Toby.’ That’s the thing you react to, not the whip.”26

Burton, Morrow, Asner, and other cast members appeared on television talk shows like Good Morning America and Dinah! to promote Roots and to show that the black and white actors held no animosity toward each other, despite the racism and brutality they had depicted on screen. These interviews helped persuade at least one viewer that she could watch the series. “I could not watch Roots until the final episode,” she wrote to Haley. “I had seen you on TV before Roots and realized I could not watch it. Too horrible. My family did watch. But for me, it was like the movie Jaws . . . I had to read all the background into the filming of Jaws before seeing it. This is the same. Now that I have heard that they called in a whip expert (a whip—expert???) and that LeVar and Vic are friends and that Vic did not handle the whip, etc. Then I can see Roots.”27 Like this elementary school teacher from Fairfax, Virginia, many viewers interpreted Roots in relation to the vast array of promotional material and interviews about the series that circulated across different print and broadcast media. Knowing “how the scenes were filmed and that it’s not really happening,” as this viewer put it, gave audiences more to think about and talk in relation to Roots. Viewers had different levels of investment in seeing Roots as real or fictional, and these personal interpretations and the discussions and debates that often followed helped Roots become a cultural phenomenon.

While the whipping of Kunta Kinte/Toby is the series’ most iconic and referenced moment, the scene was only five minutes of a twelve-hour series and is a misleading way to remember Roots. Roots did not linger on whippings and physical brutality but instead featured a range of relationships and emotions. The series, for example, features several scenes of the enslaved characters interacting in their own spaces, out of sight of the white characters. These scenes gave viewers a sense of the interior lives of the black characters. Haley’s Roots devoted dozens of pages to these slave quarters’ conversations. Haley said he was inspired by interviews with formerly enslaved people conducted by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s. “The fact is that most slaves were innately as smart as their masters,” Haley said. “There wasn’t a single slave who wasn’t smart enough to lull white folks into thinking he was ignorant. . . . What whites seldom realized was that through a highly effective grapevine, nearly every slave out in the cotton fields learned in minutes just about everything that went on in the ‘big house,’ even behind closed doors. . . . Yet their masters knew next to nothing about them.”28 The scenes were important to showing enslaved characters experience emotions beyond pain and suffering. Describing a courting scene between Kunta and Belle, John Amos said the scene “gave us a chance to refute, not just stereotypes about men and women who were in the institution as slaves, but it also made the audiences appreciate this relationship and the pressures of it, which this man and woman tried to have some sense of normalcy in their lives.”29

These scenes in the slave quarters also offered some moments of wry humor. Viewers heard about American colonists defeating the British through a dinner conversation among Belle, Fiddler, and Kunta:

BELLE: I’ve never seen white folks carrying on so. They all so happy, they can’t believe it. They keep saying over and over, “The British have surrendered. The war is over, the war is over. Freedom is won.”

FIDDLER: Ain’t that just fine, though? White folks be free. I’ve been worrying and tossing at night about them getting their freedom, been the mostest thing on my mind. Sure is one happy nigger now. Don’t have to worry about them poor white folks no more.30

This brief exchange unsettles the usual chronology of American history, marking the nation’s independence day as just one of the thousands of days before and after the Revolutionary War that black people were held in bondage. This scene calls to mind Frederick Douglass’s “What to a Slave Is the Fourth of July?,” where Douglass told an audience of New York abolitionists in 1852, “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice. I must mourn.”31 Roots is an American story, but it is organized around the dates that are important for Haley’s generational story, not the usual dates found in US history textbooks.

Director David Greene described Roots as a soap opera, and like any good melodrama, Roots involved a lot of talking. Some of the best lines came from Kunta’s daughter Kizzy. In Haley’s Roots, Kizzy and the other female characters were underdeveloped. Haley tried to inhabit the characters in his book, but he admitted this creative process worked better for the male characters. “If you feel the emotions of the characters as you are writing about them you can better deal with them, you can sort of sense what they are, what makes them tick,” Haley said. “When I was writing Kunta Kinte, I was Kunta Kinte during the various stages of his life. There were times when I was Chicken George and so forth. . . . I didn’t tell myself to identify. I simply identified on the basis of what I was writing.” Reflecting on characters like Binta, Belle, and Kizzy, Haley said, “I found more difficulty trying to feel what the women felt who were characterized in my book. Obviously, I identify more with male characters because I am a man, and for that reason I guess it was more difficult for me to feel the emotions of the female characters.”32 Haley also viewed his genealogical story in decidedly patriarchal terms, despite the important role his Cousin Georgia and other female elders played in passing down the family history. In Haley’s typed notes, for example, he described envisioning the millions of Africans who endured the Middle Passage, and “among them, one human grain of sand, my own great-great-great-great-grandfather, Kunta Kinty [sic]; his testes containing the rest of us.”33 Indeed, Kizzy does not appear in Haley’s early versions of his family history, and when she does show up in later drafts she is little more than a generational bridge to get from Kunta Kinte to Chicken George.

There were no women writers or directors on the Roots television series, and the male production team was not necessarily more attuned than Haley to creating credible female characters. What the television series had on its side were several talented black actresses, such as Cicely Tyson, Madge Sinclair, and Leslie Uggams. Uggams, who played Kizzy, had the largest and most demanding role. Whereas LeVar Burton and John Amos shared the role of Kunta Kinte, the producers used makeup and state-of-the-art prosthetics to allow the thirty-three-year-old Uggams to play Kizzy from a teenager into her seventies. Uggams also had to portray a wider range of emotions than any other character. Over the course of three episodes, Kizzy learns the family history from her father, Kunta; is sold away and separated from her family; is raped by her new master, Tom Lea; gives birth to the son produced by this rape, Chicken George; and becomes the matriarch for a community of enslaved people. Uggams, who was best known for performing in musicals and variety shows, said, “A lot of people were shocked, they didn’t expect that I was capable of portraying something that heavy.” Like her black cast mates, Uggams found Roots rewarding but emotionally challenging. “I would come home [after filming] very, very angry,” Uggams recalled. “I made a lot of phone calls to my mother and father and talking about my grandmother and great-grandmother and how could they put up with this.”34

Uggams’s best scenes come opposite Sandy Duncan, who played Missy Anne Reynolds, the niece of Dr. William Reynolds, who owned Kizzy and Kunta. In one scene, Kizzy helps Missy Anne select clothes for dinner and Missy Anne confides in Kizzy about her romantic involvement with a distant cousin. The characters talk almost as friends, and viewers learn that Missy Anne taught Kizzy to read, a secret they need to keep from Dr. Reynolds. “You keep my secrets and I’ll keep yours,” Missy Anne tells Kizzy. “I’ll protect you, Kizzy, I’ll always protect you.”35 Moments later, over a picnic in a meadow, Missy Anne tells Kizzy that her uncle is planning to gift Kizzy to her. “You’ll be my slave, Kizzy, we’ll be together for ever. And you’ll never have to be afraid again, because I’ll protect you, Kizzy.” Kizzy gently protests, “There seems just so much happening all of the sudden.” The exchange that follows is one of the most didactic moments in the series.

MISSY ANNE: It will be better than ever for you and me, Kizzy. And it will be legal. You hear me, Kizzy? Legal.

KIZZY: Don’t know nothing about legal.

MISSY ANNE: Well, legal is . . . it’s just the law. Black people are slaves and white people own them. That’s just the way it is.

KIZZY: I know. Just don’t understand it, I guess.

MISSY ANNE: Well, think of it this way, Kizzy. It’s the natural way of things. I suppose it’s because white folks are just naturally smarter than niggers. Like men are smarter than women. Now, everyone knows that for heaven’s sake.

KIZZY: You mean that’s the way God made it?

MISSY ANNE: Exactly. So if it wasn’t right, now he’d change it wouldn’t he?36

Producer Stan Margulies described this episode as the “one out-and-out woman’s show in the series,” and as in a melodramatic soap opera, this scene works because Uggams and Duncan wring additional emotion and meaning out of the script.37 Duncan is upbeat as she delivers her lines, giggling and smiling while explaining the naturalness of slavery and patriarchy. Uggams’s face registers confusion, but also a sort of wiliness as Kizzy draws Missy Anne out. Missy Anne is repeating rationales for slavery that outlived the peculiar institution and propped up romantic visions of plantation life. Roots undermines these views by pushing the idea of childhood friendship between slaves and masters to a ludicrous extreme. “Kizzy, don’t you want to be my slave?” Missy Anne says near the end of their conversation, slightly offended. “Aren’t you my friend?”38

In the television series Kizzy has a character arc, and a chance for a small measure of revenge, that she is denied in the book. Decades after she is sold way from the Reynolds plantation, a horse-drawn carriage arrives at the Lea plantation with a familiar passenger, Missy Anne. Kizzy recognizes Missy Anne, but Missy Anne pretends not to remember her old “friend.” When Kizzy goes to get Missy Anne water, she spits in the cup before delivering it to her. This was not initially in the script, but Uggams and director Gilbert Moses talked about how to conclude Kizzy’s storyline. “Something had to happen to put a button on this relationship,” Uggams said.39 It was a small victory. Kizzy remained the property of the man who had raped her and fathered her son, Chicken George. Still, Roots asked viewers to see Kizzy as more than just a bridge connecting the male members in Haley’s family history.

Figure 20. Kizzy Kinte (Leslie Uggams) talks with Missy Anne Reynolds (Sandy Duncan).

The eight episodes of Roots are uneven. The producers spent much of the budget on filming in Savannah, hoping the opening episodes would hook the audience. Back in Hollywood, Roots filmed at the Hunter film ranch near where Planet of the Apes and dozens of others films and television shows were filmed. The plantation house was just a facade created by the production designer, and the producers were constantly asking ABC for more money to hire “extra extras” so that the plantation scenes did not look too sparsely populated.40 Writer Bill Blinn lamented the lack of budget for the later episodes, which he described as looking “like Bonanza with a lot of black actors.”41

Television audiences did not seem to mind. When the ratings came after the last episode aired on January 30, 1977, Roots was the most watched television series of all time, displacing Gone with the Wind. Over one hundred million people saw the final episode, and Roots held seven of the top ten spots on the list of the most viewed shows of all time.

In letters and newspaper accounts, viewers described the experience of watching Roots in vivid detail. Watching Roots “hurt at physical and psychic levels in [the] most excruciating ways,” civil rights activist and FCC commissioner Benjamin Hooks said. “It gagged at the throat, throbbed at the temples, burned behind the eyeballs, ripped at the gut, tugged at the chest. At times, I would have to shut off the set and walk out of the room, ears burning, knees wobbly. But back I would come for more, enthralled at the television rendering of this emotionally searing drama.”42 A black public relations director in Nashville said, “My children and I just sat there, crying. We couldn’t talk. We just cried.” A white secretary in New York responded similarly: “It’s so powerful, it’s so distressful, I just feel awful, but I’m glad my children are watching.”43 For black artist James William Donaldson, Roots also resonated with his present-day family. “I was watching ‘Roots,’ the episode where Kizzy is taken from her parents . . . and all of a sudden I felt this welling up of emotion,” Donaldson said. “I went to my daughter’s bedroom and kissed her, thankful that she was with me and could not be taken away like Kizzy.”44 Other viewers interpreted Roots in the context of US race relations in the late 1970s, seeing the show offering support for policies like affirmative action or busing. For many viewers Roots was both intensely personal and very public, with audiences gathering to watch Roots at bars, community centers, and libraries and talking about Roots at offices, schools, and churches.

Figure 21. Patrons watching Roots at a bar in Harlem. John Sotomayor/The New York Times/Redux.

Everyone had an opinion on Roots. Ronald Reagan, former governor of California and future president of the United States, was not a fan of the show. “Very frankly, I thought the bias of all the good people being one color and all the bad people being another was rather destructive,” Reagan argued.45 The opinions of people less famous than Reagan were published as letters to the editors of newspapers across the country. These letters make it clear that viewers found very different meanings in the miniseries. Many saw the series as casting new light on black identity. “After viewing the movie and reading the novel, I shall never be the same,” a woman wrote to the Los Angeles Sentinel. “It gave me a sense of pride and dignity. I cried with the characters, I laughed with them, I felt their lashes, understood their agony. The outstanding thing about ‘Roots’ is that it was written by a black man, about a black man and his courage and determination to hold onto his true identity.”46 A viewer in South Carolina wrote, “I viewed the movie ‘Roots’ in its entirety and can truly say it has opened my eyes and the eyes of many others to our black ancestry. I have been told and have read many versions of the past from which the black race descended but could never actually visualize how our ancestors struggled for freedom, therefore, the past has been meaningless.”47 Dozens of other letter writers approached Roots in terms of white guilt and innocence with regards to slavery. “Should we be punished for the sins of our fathers?” a viewer from Seattle asked. “I feel that what happened wasn’t something the white race did to the black race. Not all black people were involved and not all white people were involved. I don’t feel we should look at it today as ‘something I did to you,’ because ‘we’ did not exist then.”48 A viewer from Indiana was more direct: “Inasmuch as my own foreign born granddaddy didn’t have lots of spare time for oppressing black folks while struggling with a new language and working in Chicago’s stockyards; my own personal guilt is rather low.”49 In Pasadena, a “Seething Southerner” wrote a letter describing her worries about what children might learn from Roots. “My family and I have just sat in front of our TV screen watching ‘Roots,’” she wrote. “I’m seething. . . . If there was ever a distorted piece of propaganda ‘Roots’ is it. I’m not saying any of that didn’t happen: what I am saying is that anything which pictures every white as vicious and heartless, and every black as sweet, good and a helpless victim, is an out-and-out lie. The thing I hate in this is that children are going to believe the lie.”50 This opinion prompted a reply by a writer who signed her letter “Kizzy”: “Why doesn’t ‘Seething Southerner’ read books on slavery. Why not come to Northwest Pasadena or Altadena and talk to old people who came out of the South, whose mothers were the ‘Massa’s’ children, like my mother.”51 In newspapers across the United States viewers debated, praised, and criticized Roots, making connections among the television miniseries, what they believed about slavery, and their own family histories. All of this amounted to one of the first national conversations on race, with all of the hope, ambiguity, and futility that this Clinton-era phrase evokes.

Critics wrestled with what it meant that millions of Americans had read and watched Roots and were suddenly talking about race and slavery. “The essence of the racial struggle in America has not been physical, or legal, or even spiritual,” Roger Wilkins wrote in the New York Times. “It has been existential, about truth and falsehood, reality and illusion. The ABC television series offered one black man’s vision of historical reality—more or less shared by millions of his black countrymen—and spread it large before the American people. In that sense, ‘Roots’ may have been the most significant civil rights event since the Selma to Montgomery march of 1965.”52 Texas congresswoman Barbara Jordan argued that Roots benefited from a quieter period in race relations. “Everything converged—the right time, the right story and the right form,” Jordan said. “The country, I feel, was ready for it. At some other time I don’t feel it would have had that kind of widespread acceptance and attention—specifically in the ’60s. Then it might have spawned resentments and apprehensions the country couldn’t have taken.” Jordan’s Congressional Black Congress colleagues Charles Rangel and John Conyers noted both that Roots could be enlightening and that it would not change the social and economic standing of black Americans. Rangel stated, “It helps people identify and gets conversations started, but I can’t see any lasting effect.” Conyers argued, “It doesn’t cure unemployment or take people out of the ghetto. But it’s a democratic statement as eloquent as any that’s ever been devised.”53

Television stations in over fifty nations broadcast Roots during the next two years, including stations in West Germany, Japan, and Nigeria. These global viewers watched the show in varied local and national contexts. In West Germany, Roots provoked some of the first discussions of the Holocaust in German broadcasting.54 In Japan, Asahi National Broadcasting Company director Naohiro Nakamura admitted, “Japanese audiences usually prefer something about white people [in foreign films], and we were not very interested at first.” Asahi eventually bought rights to show Roots from Warner Brothers after deciding the series was “high quality” drama that was “not too artists, not too high-brow” for Japanese audiences.”55 In Nigeria, Roots prompted public discussions on slavery and fueled government demands for reparations a decade later. Broadcasters and political interests in South Africa and Brazil, in contrast, refused to import Roots for fear it would support black freedom struggles in those nations, while US diplomats in each country organized private screenings of the series. Warner Brothers, in selling Roots to global broadcasters, billed the series as “the world’s most-watched television drama.”56

If Roots had a critical flaw, it was that it made the history of slavery about people and their feelings rather than about systems of power and capital. In Time’s cover story “Why ‘Roots’ Hit Home,” the magazine noted that Roots had “sensitized” people to black history but wondered, “Sensitized in what way? How long do white Americans need to feel guilty about the evils committed by their ancestors? Is there a statute of limitations on guilt?” Roots’s emotional appeal reached millions of people, but it also invited viewers to make the series about their own emotional needs. Black journalist Chuck Stone described Roots as “an electronic orgy in white guilt successfully hustled by white TV literary minstrels.”57 Producer David Wolper probably would have objected to being called a “white TV literary minstrel,” but he would have agreed that Roots catered to the desires of white viewers. “Remember, the television audience is only 10 percent black and 90 percent white,” Wolper said after Roots’s record-breaking run. “So if we do the show for blacks and every black in America watches, it is a disaster—a total disaster.”58

Roots was pitched to white audiences, but so was nearly every other show in US television history. What made Roots unique was that it asked television audiences to identify with the lives, emotions, and struggles of a host of free and enslaved black characters. This was groundbreaking in 1977, and the four decades since Roots have underscored how uncommon it is to have black actors, culture, and history featured in a mass commercial production.