Freedom

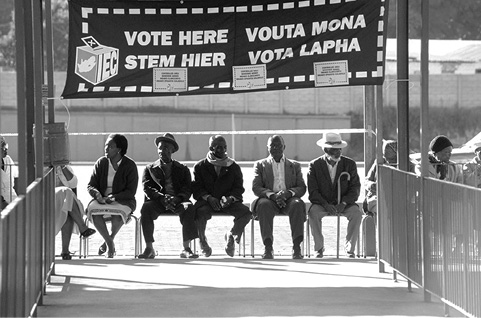

Suddenly, freedom is no longer coming: it has arrived. The date is 27 April. The year is 1994. On this day, black South Africans gain full citizenship rights and white South Africans begin to put the stain of racist shame behind them. The occasion is momentous.

In countless acts across the country, as the day unfolds white and black South Africans move towards one another like newlyweds about to take a vow.

Until this point, whites have collectively been skittish about the impending day. They are afraid of how their lives will change. For so long they have understood the world in terms that are either black or white. Over-simplification has been a key ingredient in apartheid’s success. Now they are thrust into a world of grey – of doubt and anxiety and exhilaration.

Despite their full participation in the steps that have led them here, many whites remain fearful of what this new era might bring. On this bright autumn day, they let go.

The letting go has been months in the making. Jingles have played on the radio and television every day imploring us all to respect one another, to give peace a chance. Brenda Fassie’s ‘Black President’ has been on heavy rotation in shebeens and nightclubs across the country, getting us ready for Nelson Mandela’s confirmation as president of the Republic of South Africa. Posters in the green, black and gold of the ANC and the orange, blue and white of the National Party (NP) adorn streets in every city. Political rallies fill stadia, crowds roar their jubilation, singing, ‘Viva the ANC, viva! Long live the spirit of the UDF, long live!’ We race towards our destiny.

When the day finally comes it is both climactic and oddly underwhelming. On one hand there is joy and noise and celebration. On the other is a barely audible sound. It is apartheid’s long slow hiss into obsolescence. Quite suddenly apartheid has lost its spectral force. It is a demon defeated, no longer a Klansman on a horse inspiring fear in the hearts of black people. The night rider who terrorised us for so long is revealed for what he is: a little boy in a billowing sheet with cut-out eyes. Sitting perfectly still underneath the uplifted sheet, he is peculiar and sad. He looks like he is trying to disappear.

This revelation of this unveiling is greeted by a surprised moment of silence. But it is only a short pause. Within seconds South Africa is hurtling towards democracy.

In the streets and across great swathes of rural country, the euphoric young rub shoulders with those who are simply grateful that they have lived to see this day. Old women achingly bend and tremblingly mark; they silently cross and dutifully fold.

Even before papers are counted, victory is assured. The authority of those who have for so long been the wretched of this land is unmistakeable. ‘Lililililili!’ Ululation fills town halls and ripples through trees and across valleys, lifting in the wind.

Hands wave, bedecked in white gloves; we are isicathamiya and maskandi music. We are Hugh Masekela’s husky voice, we are the breath in his trumpet, a long purple note of freedom. We are slave quarters rising like hips to greet a lover long lost and now found; we are an embrace where two oceans meet.

On this day, even the weather complies with our wishes. There are no rains, only blue skies and a stillness in the reeds. God has decreed that today nature will not interfere with the triumph of humanity.

And so, with our landscape serving as a steady backdrop, we move and we groove, we sway and we sashay, starting in the fairest Cape and ascending north towards the mighty Limpopo. Watch! See how we shimmy, how we weave our bodies in a timeless domba. We are the sacred Venda python sloughing off our old skins as we enter history’s gates. We are majestic; glistening into the future, we wind and we wend and we dance ourselves to exhaustion. As the moon rises we know that soon, when the votes are counted and the results are announced, we will finally be free.

* * *

As South Africans rise to begin their day – to cast their ballots – I am in Minnesota, driving towards Chicago in a rented minivan. In the car with me are two Mandlas, a Kgomotso, a Lunga, a Sbusiso and a Rogene, all of us students at various universities in the Midwestern state of Minnesota. We are on our way to the South African consulate, determined not to miss out on history.

We arrive at the consulate and we are ushered into a small waiting room and then into the area where we will vote. We left very early in the morning; I stand in the sterile booth under dead fluorescent light. Until now, I would have had no cause to be in this building; the consul would have turned me away. In one fell swoop this has changed. The irony of this hits me hard as I look at my identity document.

I am twenty years old, about the same age that Baba was all those years ago when he left South Africa. I mark my ballot with a vote for Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress.

Afterwards, I look for a phone. I have topped up my AT&T calling card in anticipation of the lengthy call. The phone rings in Durban, thousands of kilometres away, and Zeng picks up. I ask excitedly, ‘How was it?’ At fifteen she is too young to vote, but she has no trouble answering my question. ‘Amazing, Sonke. I wish you were here.’ She is in high spirits, and her voice has the quality of bubble gum; it carries across the static in the line like pink and blue glitter thrown into a breeze. She describes everything: the exuberance of the crowds, the fear that it might all go wrong; the hilarity of two old white women insisting on jumping the queue even as democratic elections were taking place that sought to put an end to that sort of behaviour.

She laughs and, with her special brand of social commentary, she does a faux newsreader’s voice, saying, ‘Here, reporting live from the frontlines we have Mrs Smith. So, Mrs Smith, you want to skip the line because you’re white? What are you voting for then, Gogo? I think … yes, Mrs Smith, I can confirm that you get to stand at the back of the queue like everyone else, the old days are over!’ We laugh uproariously, grinning at what a long road it will be for some white folk, our missing each other tangible through our laughter.

The phone is passed around. I speak to everyone – cousins and aunties and uncles. The house is full of relatives and friends who have come to share the day with us. Ours is the home where everyone has begun to congregate in the year since the family has ‘returned’ to Durban.

Finally Baba is on the line. I clutch the telephone receiver as though by force of will it might transport me to Durban. ‘So, you are in Chicago?’ he asks. ‘Yes, Baba,’ I respond, trying to pretend that I am not overwhelmed by the sound of his distant voice. ‘Well that’s good,’ he says, ‘I am glad you made it.’ We are quiet for a while, suddenly unsure what to say. Then he says what I have been waiting for him to say. ‘Here we are, Sonke-girls.’ He uses his affectionate name for me.

He laughs and then says awkwardly, almost in a whisper, as though he can’t believe it himself, ‘We did it. We are free.’

That X marked in a voting booth in Chicago marks my spot in history. It marks my place in a new nation at the start of a new era.