5

Resource Commensurability

and Ideological Elements of

the Exchange Relationship

Judi McLean Parks

Washington University in St. Louis

faye l. smith

Missouri Western State University

Thomas Jefferson captured the recalibration of work's standing when he described the young American nation as “an aristocracy of talent and virtue.” Ever since, what each of us does for a living has been an expression of identity and a measure of worth.

—The Week, June 19, 2009, p. 25 (emphasis added)

INTRODUCTION

Part of our very identity and our sense of self-worth may be derived from our work. As part of the larger exchange relationship, ideological exchanges are characterized by perceived obligations to support specific causes or ethical principles (Blau, 1964; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003). For example, in 2002 Professor Bernard Amadei started Engineers Without Borders USA (EWB-USA) after he and eight engineering students, working with a local community, installed a sustainable and low-cost clean water system in San Pablo, Belize. In 8 years, EWB-USA has grown to 12,000 members with more than 350 projects in more than 45 developing countries (Engineers Without Borders, 2011). The work that is done by the many engineers and other professionals (e.g., anthropologists, sociologists) provides a source for ideological elements that enhance their identity and sense of self-worth. It is the ideological elements of exchange relationships that are the focus of this chapter.

Exchange relationships typically have been seen in terms of one of three currencies between worker and organization: economic or transactional currencies, socioemotional or relational currencies (McLean Parks, Kidder, & Gallagher, 1998; McLean Parks & smith, 1998; Rousseau & McLean Parks, 1993), and more recently, ideological currencies (Thompson & Bunderson, 2003). Yet these three currencies are not created equal(ly), not only in terms of what resource it is that comprises the exchange, but also in terms of their implications for employee attitudes and behaviors. This chapter focuses primarily on exchanges involving ideological currencies and incorporates their key elements into our theoretical framework:

1. We develop a categorization of the sources of the exchange elements. These elements have implications for exchange relationships and ideological exchanges in particular. These sources are pecuniary, task, role, relational, organizational, and occupational and form the foundation of the inducements of the work relationship.

2. Based on these sources, we build the logic of pivotal ideological space that is created by the ideological resources that are exchanged.

a. Further, pivotal space can be described in terms of depth and breadth, indicating how embedded the ideology is within the work relationship. Although certainly pivotal space can transcend ideological exchange, it is in the context of ideological elements that we frame our discussion.

b. We extend the framework further to address ideological incompatibility, ideological crystallization, and meta-ideological exchanges.

3. We refine the notion of resource commensurability in exchange relationships (McLean Parks, 1997; Shore et al., 2004), refining Pruitt's (1981) classification of specific, homologous, and substitute forms of compensation as well as Sparrowe, Dirks, Bunderson, and McLean Parks (2004) specification of isomorphic compensation (see also McLean Parks & smith, 2006; Shore et al., 2004).

We focus on these aspects of the relationship as we believe they are important for ideologically based exchange, representing thorny issues and complexities beyond those found in exchanges based primarily in economic or socioemotional currencies. Perhaps more than any other form of exchange, ideological currency is important because it gets at the very soul of the worker. As a result, ideological exchanges can enhance and affirm a worker's identity in terms of the value the worker places on the cause that the ideology supports. The ideologically infused relationship can be one of the most effective mechanisms for binding workers to an organization, encouraging effort over withdrawal (e.g., Kidwell & Bennett, 1993), identification (e.g., Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Dutton, Dukerich, & Harquail, 1994), extra-role behavior (e.g., Van Dyne, Cummings, & McLean Parks, 1998), and other positive contributions to the organization and its outcomes. Paradoxically, the ideological exchange also can result in perhaps the highest levels of disaffection if the organization's support of the ideology diminishes, severing the relationship and resulting in withdrawal behaviors (e.g., Kidwell & Bennett, 1993), a sense of violation (e.g., Morrison & Robinson, 1997), or even moral outrage (e.g., Bies, 1987).

This conundrum can, in part, be understood in terms of the ideological work elements that are incorporated into ideological currencies. Building on McLean Parks and smith's (2000, 2002) identity frames, we present a model of ideological elements by which the ideological currency of the exchange is provided by pecuniary, task, role, relational, organizational, and occupational work elements. To the extent that each of these ideological elements is jointly affirmed by one another, a pivotal ideological space is created, which strengthens and deepens the ideological exchange.

THEORETICAL DEVELOPMENT

Exchange Elements: Pecuniary, Task, Role, Relational, Reputational, Organizational, and Occupational

March and Simon (1958) argued that the workers’ decisions to participate is based on a balance of payments to members for participation in the organization. These payments comprise inducements exchanged by the company in return for the workers’ contributions (effort, skills) to the organization, whereby the worker continues to contribute so long as the inducements received are greater than their contribution. However, this perspective has been largely silent on what actual resources might comprise those inducements. The literature on psychological contracts has helped to fill this theoretical gap with the delineation of transactional/relational and economic/socioemotional (e.g., MacNeil, 1985; Rousseau & McLean Parks, 1993) categories for the exchanges embedded in these relationships.

In this section of the chapter, we delineate and define different types of inducements found in the relationship between workers and their organizations. We argue that organizational inducements include a number of different elements and that these elements can be generally categorized by their source. The elements are resources that the organization controls through decisions and policies, whether formal or informal. For example, a work area may be furnished with ergonomic furniture and equipment, or it may be furnished with out-of-date, dilapidated furnishings. In the first scenario, the resource of office furnishings communicates caring and respect, whereas in the second, the resource provided elicits the suggestion that people are not valued. Similarly, organizational policies are designed to provide standardized criteria and processes for organizational decisions, and when the policies are designed and applied in a fair and consistent manner, the socioemotional resource of “respect” may be part of the set of inducements.

The general sources of the elements in the exchange relationship—the collection of perceived inducements—that we have identified include pecuniary, task, role, relational, organizational, and occupational sources. Note that it is possible that a given element may have characteristics of more than one source. In other words, these sources are not mutually exclusive. For example, task and role elements may have aspects that spill over into the relational domain (e.g., status conferred by role elements). Further, although we believe that the sources we have identified are among the primary sources, our list may not be exhaustive but is a starting point for further development of the actual types of resources found in exchange relationships.1 We use these elements to refine our understanding of the interaction of resource inducements, in particular, as it applies to ideological exchange.

In the context of the exchange relationship, these elements, to a greater or lesser extent, can create and enhance the identity of the worker. While in the transactional exchange, identity creation/enhancement is largely irrelevant (McLean Parks & smith, 1998), in the relational, socioemotional exchange, the role of identity may be relatively minor or an important aspect of the relationship (McLean Parks & smith, 1998). Ideologies by nature are particularistic (Foa, 1971; Foa & Foa, 1975); in other words, they are uniquely nonsubstitutable. Thus in the ideological exchange, identity is paramount, not only from the perspective of the worker's personal identity, but also the identity of the organization. For example, the motto of Origins, a cosmetic company that eschews animal testing, is “powered by nature, proven by science” and its mission statement notes, “…our long-standing commitment to protect the planet, its resources and all those who populate it is reaffirmed by our earth and animal friendly practices, packaging and policies” (Origins, 2010). Here the values associated with animal rights are reflected in the identity of the company in their “animal friendly practices” and lack of animal testing. Continuing the example, the causes valued by workers may become part of their personal identities—who they are as a person. Perhaps a worker at Origins sees herself as a mother, a chemist, and an animal rights advocate. These are all aspects of her identity. In this case, these three respective identities mirror one another and are mutually enhancing and reinforcing. However, if, in response to a personal injury lawsuit over one of their products, Origins were to begin animal testing, their (original) goals have become displaced (Blau, 1964; Merton, 1957; Thompson & Bunderson, 2003). As a result, our chemist's ideological contract has been breached, and her identity is no longer enhanced by that of her employer.2

In this way, ideological exchange elements, which comprise inducements through which workers choose to participate, can be identity affirming (Steele, 1988) or disconfirming. Possibilities and potential also are components of one's identity: what might be or who one might become in the future (Christiansen, 1999). For example, someone who joins the Peace Corps is likely to share organizationally espoused and enacted values, including the value of future peaceful and developmental opportunities that can result in positive contributions to countries in need. This future focus may be important in ideological exchange, where the causes themselves focus on a potential for a better future (e.g., for children, animal rights, peace on earth, the environment). We further argue that the extent to which these elements contain ideological aspects and to which the elements are jointly affirmed by one another creates a pivotal ideological space, which can be described in terms of two dimensions: breadth (the degree of overlap among elements) and depth (number of sources that contribute to the pivotal space). Within this framework, we also discuss ideological incompatibility and ideological crystallization. The depth and breadth of the pivotal space, as well as ideological incompatibility and crystallization and associated meta-ideological exchanges, have implications for commensurability in the execution, fulfillment, and violation of the work relationship grounded in ideological exchange. We now turn to the definitions of each of these constructs.

Pecuniary elements are characteristically economic resources. These are the resources typically ascribed to the transactional exchange and can include wage/salary, bonuses (or penalties/fines), benefits, and other monetized inducements (Rousseau & McLean Parks, 1993). Pecuniary elements typically are fungible and, hence under some circumstances, may be substituted for other elements. However, pecuniary elements can take on the mantle of other elements. For example, if workers believe that they are underpaid (pecuniary) relevant to referent others, the inequity also may communicate that they are less valued, and if known to others, the pecuniary element of underpayment may impact their standing in the organization and the respect conferred (relational) on them by colleagues. Pecuniary elements that have overtones of ideological currency might include matching contributions by the company to the specific cause valued by the worker.

Task elements are specific actions (behaviors) needed to execute one's job at work. How an organization constructs its tasks and communicates their value (to the organization and society at large) is another resource element that can provide an exchange inducement. Hackman and Oldham's (1976) Job Characteristics Model specifies that workers experience meaningfulness when tasks use a variety of their skills (task variety), are significant (task significance), and help create a “whole” (task identity), rather than just one cog in a wheel. Meaningful tasks communicate that workers are valued and hence may induce full participation in the organization. Further, in ideological exchange, meaningfulness may be paramount. Specifically, in ideological exchanges, ideologies are permeated with meaning, and in part, it is that meaning itself that attracts the worker. When the task's meaningfulness is congruent with the meaningfulness of the ideology, this relationship is strengthened.

Role elements are rules and norms that create expectations held both by individuals and by others. They include rules or norms that comprise a blueprint or script that guides behavior and choices (Biddle, 1979), implicitly or explicitly specifying appropriate goals, tasks to be executed, and the like. Roles contain both prescriptions and proscriptions (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964) and delineate mechanisms through which objectives are achieved. The blueprints provided by role elements represent ascriptions or characteristics that shape the workers’ personal identities (Allen & van de Vliert, 1982), even though the role elements may be outside the parameters of the workers’ direct control (Linton, 1936). Regardless of whether or not they have control, when workers view the role ascriptions as constructive and legitimate, they will not only incur costs to conform to role norms, prescriptions, and proscriptions, but they also will incur costs to punish those who do not conform (Biddle, 1986; Goffman, 1959, 1961). Willingness to incur these costs will be increased when the exchange is ideological.

Relational elements are social and interpersonal aspects of the work environment and thus are socioemotional in character. As noted by McLean Parks and smith (1998), relational exchanges “encompass the full range of resources, including those which are unobservable” (p. 133). Relational elements may include opportunities to form friendships and trusting relationships at work, contributing to workers’ formation of relational identities (Andersen & Chen, 2002; Sluss & Ashforth, 2007). Relational elements of the exchange provide reflected appraisals, which enhance self-esteem (Cooley, 1902; Mead, 1934). Relational elements can produce positive interactions with other workers and supervisors, customers, or suppliers, endowing workers with respect of peers and contributing to a positive self-image and reputation. Further, relational elements can be particularistic, where identity becomes paramount. When particularistic resources are involved, they represent more of the individual. As a result, “if the contract is breached, then the loss felt will be more salient and personal” (McLean Parks & smith, 1998, p. 134). For example, relational elements affecting ideological currency might include one's reputation enhancing or tarnishing fellow workers’ reputations because of the company they keep.

Organizational elements are the implicit and explicit benefits derived from one's membership or association with the company. As the organizational identity literature attests, workers’ identities can be enhanced or damaged through their organization. During the height of the controversy over genetically modified foods, Monsanto, the agri-pharmaceutical giant, found its previously positive reputation damaged. Protestors in Europe shouted “Ban Frankenfood” and “Die Monsatan” (Schurman, 2004), virtually bringing an entire industry to a complete halt (Miller, 2004; Schurman, 2004). At the time of the protests, especially at its European locations, being an employee of Monsanto carried significant costs, and the spillover to one's personal identity was negative. More recently, British Petroleum's (BP) Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico not only tarnished the reputation of BP, but also cast a shadow over its employees (Gnau, 2010). In each of these examples, the organizational element had a direct effect on the ideological exchanges with workers whose valued causes were environmentally focused.

In sum, organizational elements can be a source of self-esteem or identity or, when negatively evaluated, of disidentification (e.g., Dukerich, Kramer, & McLean Parks, 1998; Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001) and alienation. In the case of ideological currency, elements related to the ideology or cause are key to the exchange. If viewed positively or as supporting/enhancing that ideology, it will strengthen the work relationship, increasing commitment and the willingness on the part of the worker to go beyond role requirements. In contrast, if viewed negatively or as lacking support or detracting from the cause, it may result in greater turnover, a lack of motivation, and even sabotage (McLean Parks, 1997).

Occupational elements are benefits derived from one's work specialty or profession. Research on occupational prestige has found that different occupations provide different levels of prestige (Nakao & Treas, 1994; Spaeth, 1979) and being able to ply one's trade in the professions may be one inducement for a worker to join a specific organization. Any given organization may involve a number of different occupations (e.g., scientist, secretary, accountant, and janitor). Thus, although clearly related, we regard the occupational and organizational elements as distinct and separable, with potentially different effects. Logically, we can imagine situations where they are distinct. For example, working as an accountant (occupational element) for Tom's of Maine after the Enron fiasco may have been associated with negative spillover from the accounting profession. However, working for a firm known for its development of earth-friendly personal care products such as those produced and sold by Tom's of Maine may have been a positive inducement (organizational element). Thus, if accountants at Tom's of Maine focused on their occupation, they may have become disaffected. However, if their focus was on environmental issues, their tie to the organization may have enabled them to withstand the negative spillover from the Enron accountants’ actions.

In summary, the six sources of resource elements provide an initial context from which inducements contribute to ideological currency and can be exchanged to form a strong relationship between worker and organization. The elements are the source of the actual resources contributing to one's formulation of an ideological exchange. As argued earlier, the elements are not mutually exclusive and are not necessarily comprehensive, but they do provide a basis from which scholars can enrich their understanding of the actual resource elements that create and enhance exchange relationships. Based on these elements, we now turn to the development of the concept of a pivotal ideological space (see Table 5.1).

Features of the Resource Elements

Pivotal Ideological Space

Viewing the content of inducements exchanged in work relationships through the lens of multiple elements suggests that these elements may be “layered,” juxtaposed, and overlapped. In this way, alternative ways of supporting ideological values from pecuniary, task, role, relational, organizational, and occupational domains may be positioned against one another, revealing that these elements may be congruent or incongruent. If the former is the case, they provide complementary information concerning the organization's support for the ideology; in the latter case, a single note of incongruence may render cognitive dissonance such that the ideological exchange is breached (McLean Parks, 1997). By incorporating Schein's (1980) notion of pivotal norms, as well as earlier work (Crooker, smith, & Tabak, 2002; McLean Parks & smith, 2000, 2002), we now define pivotal ideological space as the overlap among and within ideological elements. It is in this overlap where elements are interpreted or perceived as compatible and congruent with the salient ideology. The extent to which they overlap may be large, small, or nonexistent. This overlap may be layered across all the elements (large pivotal space) or a subset of them (small pivotal space). Consistent with McLean Parks and smith's (2000, 2002) identity frames, these elements provide information such that they can be characterized as (a) conjunctive (some degree of overlap); (b) disjunctive (no overlap but also no incongruence); (c) equivalent (complete overlap); or (d) incompatible (inconsistent and contradictory).3

TABLE 5.1

Sources of Resource Elements

Source |

Definition |

Sample Resources |

Example |

Pecuniary |

Economic or monetized |

Wages, bonuses, benefits |

Salary of $100,000 |

Task |

Specific actions within roles |

Pride, identity |

Astronaut's “bragging rights” for having worked aboard the Space Station |

Role |

Rules/norms that guide behavior and choices |

Rules, norms, prescriptions, proscriptions |

Authorization to sign for expenditures |

Relational |

Socioemotional and interpersonal connections |

Friendships, mentors, trust, respect |

Mentor to junior colleagues |

Organizational |

Derived from membership |

Reputation, identity |

Being an IBMer |

Occupational |

Recognition from work specialty |

Prestige, earnings potential |

Respect and prestige derived from being a physician |

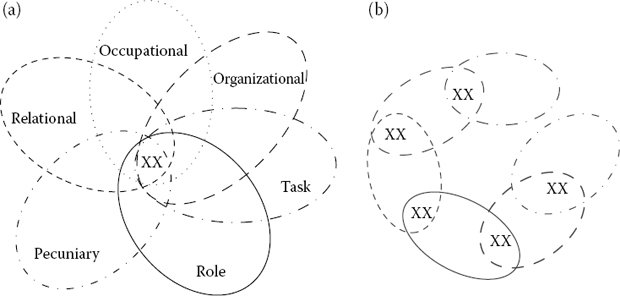

At the extremes, elements can overlap 100% (equivalent) or be disjunctive. In the latter case, the pivotal space does not exist. Pivotal ideological space is the ideology that is jointly affirmed by the content of multiple elements. For example, contributions to a shelter for abused children and allowing workers to volunteer at the shelter 1 hour a week on company time are two different resource elements (inducements) that both support the same ideological value that is important to one or more workers. Pivotal ideological space can be conceptualized along two dimensions: breadth and depth (McLean Parks & smith, 2000, 2002). The breadth of the pivotal space is the degree of overlap across the elements—the number of common or congruent elements that reinforce the ideology. In contrast, depth of pivotal space is the number of sources of inducements (pecuniary, task, role, relational, occupational, organizational) that contribute to the pivotal space. Breadth provides inducements from multiple sources, whereas depth parallels the strength of the ideological components. Thus, all of the sources may overlap in one pivotal space that is broad and deep, or one or more of the sources may contribute to pivotal spaces, such that multiple pivotal spaces that are narrow and shallow may accumulate. Each of the multiple pivotal spaces represents separate ideologies. Although not identical, different ideologies can be related to one another (energy sustainability and clean air) or unrelated (energy sustainability and disease eradication). See Figure 5.1.

FIGURE 5.1

(a) Pivotal ideological space. (b) Multiple pivotal spaces and absence of pivotal space. XX, pivotal space.

The greater the pivotal ideological space(s), the stronger is the ideological tie for the worker with emerging self-reinforcing cycles across the ideological elements. However, if support for the ideology is withdrawn by the organization, the disaffection and violation caused will be more pervasive and impact more aspects of the relationship between the company and the worker.

Ideological Incompatibility

In addition to the notion of the pivotal ideological space, ideological incompatibility enhances our understanding of ideological exchange. The pivotal ideological space implies agreement or consistency among elements, whereas no overlap results in the absence of a pivotal space. Yet the ideology communicated by each of the elements also may conflict with one another or be incompatible. Hence a subcategory of disjunctive elements (no pivotal space) is ideological incompatibility. Incompatible ideological elements are logically inconsistent with one another and in direct conflict. Yet incompatibility isn't simply the absence of a pivotal space. Lack of a pivotal space is a necessary but not sufficient condition for incompatibility. At one extreme, incompatibility implies antithetical ideologies—polar opposites. Incompatibility is the degree to which an element of the exchange “repels” another, where the elements are perceived as mutually exclusive. Because ideologies are infused with specific values (Thompson & Bunderson, 2003), it follows that ideological incompatibility parallels the incompatibility of values, accounting for their potential irreducibility and distinctiveness. Thus ideologies are value specific, irreducible, nonfungible, and distinctive. To fail to support the valued ideology may be absolutely unacceptable or a nonnegotiable in exchanges involving ideological currency (Thompson & Bunderson, 2003).

Ideological Crystallization

Chatman (1989) has extended the concept of norms (Jackson, 1966) as being more or less crystallized when there is agreement across individuals in terms of what is or is not appropriate behavior. Similarly, and parallel to their development, McLean Parks and smith (2000, 2002) applied crystallization to organizational identity frames in terms of the degree of agreement among perceivers about who the organization is. We now extend crystallization to the notion of exchange relationships. Within an organization, multiple workers may hold similar shared meanings about the resource elements that contribute to each person's exchange relationship, thus making them more or less crystallized. Thus, ideologically crystallized exchanges are those in which there is a high degree of convergence of shared meaning across individuals about the resource elements that contribute to each person's ideological exchange. We suggest that such shared meaning may be the basis for strong organizational cultures where individuals mutually and collectively understand the resource elements, resulting in a high degree of consistency from one exchange to another.

Meta-Ideological Exchange

Not only can there be a high level of convergence regarding the ideology across individuals (ideological crystallization), but this crystallized ideology also can contribute to meta-ideological exchanges. Crystallization (defined earlier) represents the shared value, whereas meta-ideological exchange occurs when those sharing the ideology collectively act in coherence with the crystallized ideologies. As noted by Simon (2004), “to be is to do and to do is to be” (p. 187). Meta-ideological exchanges can become self-reinforcing, strengthening the ties and implicitly enhancing the value of the ideological currency. Yet, when these meta-ideological exchanges are tightly coupled, violation can rapidly diffuse through the entire network.

Meta-ideological exchange occurs not only because of identification with ideology, but also through the process of identity affirmation as part of the ideological group (Simon, Trötschel, & Dähne, 2008). By sharing ideological values, parties to the meta-ideological exchange strengthen social ties through their collective and mutually supported actions taken to promote the reflected values. In this way, their action reinforces not only the ideology but also the shared identity associated with the ideologically defined social group (Simpson & Macy, 2001). In other words, meta-ideological exchanges are collective actions affirming the shared ideologies. These collective actions in turn are comprised of multiple exchange relationships embedded within the larger fabric of the ideological exchange. Further, in an organization, a tipping point or threshold (Granovetter, 1978) can be reached precipitating a chain reaction that spreads throughout the ideological group. Just as a single audience member leaving a boring concert may encourage others similarly bored to exit, so too can meta-ideological exchanges result in collective actions that affirm the ideology. For example, in 2008, several hundred faculty and students at a Midwestern university wore armbands, carried signs, and turned their backs on a controversial honorary degree recipient at the spring commencement ceremony. The degree recipient had actively fought the equal rights amendment and built a lifelong career speaking out against women in the work force. The recipient's actions sparked the protests from faculty and students who strongly believed in the ideology of gender equality and fair treatment for all (Biemiller, 2008).

In summary, resource elements from the different sources (pecuniary, task, role, relational, organizational, and occupational) each contribute to the ideological exchange, potentially creating pivotal ideological space and ideological crystallization, which ultimately can contribute to a meta-ideological exchange. To the extent that the pivotal ideological space is large, that there is ideological crystallization, and that the ideology shared by members results in actions to affirm the ideology and ideological elements, then the ideological exchange or meta-ideological exchange is more likely to be quite durable and strong.

Together, the constructs discussed so far identify “what” it is being exchanged, but do not yet address “how” the exchange occurs. By exploring the commensurability of resource elements, we are able to identify how elements can be exchanged for one another. We now address the commensurability of the resources in each of these sources and develop the notion that resource elements that have common characteristics and attributes can be exchanged more easily within the ideological exchange relationship. In other words, one element from one type of resource may be exchanged for another element in another type of resource when certain attributes are held in common. We first address resource characteristics and attributes.

Resource Commensurability and Characteristics

Foa and Foa (1975) suggested most resources could be characterized along two dimensions4: (a) the extent to which they are abstract/concrete, and (b) the extent to which they are particularistic/nonparticularistic. Concrete resources are those that can be interpreted unambiguously by outside others (Foa, 1971; Foa & Foa, 1975), such as when $1.00 is exchanged for 100 pennies (McLean Parks & smith, 1998). In contrast, abstract resources are ambiguous and difficult to interpret, even within the exchange relationship. In terms of the particularism dimension, particularistic resources are those where the identity of the exchange partner matters (Foa, 1971; Foa & Foa, 1975), such as affiliation where trust is connected to a particular individual. Nonparticularistic resources, in contrast, are fungible and can be substituted for one another, where the identity of the exchange partner or resource is not important (McLean Parks & smith, 1998). For example, dollars and pennies are both concrete and nonparticularistic, making their exchange value clear, and hence, they are easily substituted. In contrast, ideological currency is specific and abstract. Because a specific cause (e.g., renewable energy) cannot be calibrated easily against another (e.g., gender equality), substituting support for the one with the other will not be satisfactory.

These classifications and attributes of individual resources have implications for the commensurability of the resources when they are exchanged. We illustrate how ideological currencies may be more or less easy to exchange (commensurable) depending on how resource elements exemplify our classifications and attributes. For example, pecuniary elements, which typically can be quantified easily, are less likely to be exchanged for relational elements, which are particularistic (e.g., friendship for money). In part, this is because assigning specific values or rankings to a particularistic resource is inherently difficult. Likewise, ambiguous resources are unlikely to be exchanged for concrete resources, as determining the metric of exchange also will be difficult at best. Thus, the identity and characteristics of the resource elements, as well as their concrete and particularistic attributes, suggest different degrees of commensurability among resources exchanged. Ideological exchanges, where a very specific cause is valued, characteristically are both particularistic and ambiguous. We now turn to the related issue of commensurability.

The difficulty in assessing the specific worth of an ideological element that is both particularistic and ambiguous requires an enrichment of our understanding of commensurability.5 Further, evaluating the worth of ideological elements suggests that elements may or may not be more or less interchangeable. Trading support for animal rights for recycling paper products may not be seen as a fair exchange of ideologies. At least in part, this is because the underlying ideological values (humane treatment of animals versus saving trees) are not commensurate with each other. We enhance our understanding of potential substitution across ideologies (or not) by exploring the theoretical foundations of commensurability (or lack thereof) in ideological elements.

In the context of exchange relationships in general and ideological exchange in particular, there has been a relative paucity of research exploring commensurability in the organizational literature.6 This has been an unfortunate oversight, as it has implications for the potential for perceived violation in the exchange. We turn to the domains of law and philosophy where the commensurability of resources has long been of interest.

Resources that are commensurable can be precisely quantified or measured using a single metric, such as dollars, inches, or beaver pelts.7 Whatever the metric, the presumption is that if commensurable, the resource technically is infinitely divisible. Whereas rational choice models argue that only choices made between alternatives on the basis of commensurability are economically rational (Edgeworth, 1881),8 others note that some resources cannot be ranked along a single metric or divided by the lowest common denominator. They argue that no single metric can capture the richness of all types of resources and their potentially unique attributes; neither can a single metric capture the diversity in how attributes of those resources are valued in the eye of the beholder.9

In law, the commensurability or incommensurability of resources has been the subject of debate, resulting in a dichotomization of the concepts into “either/or” perspectives—that resources either are or are not commensurable (cf. Leiter, 1998). For our purposes, a more fruitful perspective is that resources, to a greater or lesser extent, have characteristics that are both commensurable and incommensurable. In this sense, we follow the logic of the philosopher, Hegel (1881/1969), who framed the argument as one of quantity (commensurable) versus quality (incommensurable). Hegel argued that quantitative changes require qualitative changes (and vice versa). Using male pattern baldness as an example, Hegel addressed this paradox. In some cultures, a qualitative distinction is made between baldness and having a full head of hair. A change in the number of hairs on a man's head does not necessarily result in a qualitative change; however, at some point, the loss of hair does become a qualitative differentiation where the man would be considered “bald.” The transition point from quantitative (losing a hair or two) to qualitative (being seen as bald) likely is subjective, but this transition demonstrates the simultaneously quantitative and qualitative aspects of the resource (in this case, hair).

The duality of Hegel is, we believe, a good one from which to understand resource commensurability of ideological elements in exchange. By recognizing that at least some resources may have characteristics both of commensurability and incommensurability, we avoid forcing the straitjacket of commensurability on all resources by attempting to fit the diversity of resources and their rather thorny attributes into one form or metric of exchange, be it money or “utils.” Quite simply, some resources can be neither effectively quantified nor easily rank ordered against other resources. It is these resources and their thorny attributes that are the most likely candidates for subjective and idiosyncratic interpretations, and hence more prone to perceived violation in the exchange relationship (Mclean Parks, 1997; McLean Parks & Kidder, 1994; McLean Parks et al., 1998; McLean Parks & Schmedemann, 1994; McLean Parks & smith, 1998, 2006; Rousseau & McLean Parks, 1993; Schmedemann & McLean Parks, 1994). We now address the types of compensation (currencies) and their attributes to develop how ideological elements may be exchanged.

The currencies in the exchange relationships identified are not created equal(ly). A critical way in which the currencies may differ is in terms of their commensurability. Pruitt (1981) introduced the idea of commensurability to the organizational literature in discussing compensation in negotiations. He argued that there are three general types of compensation in an exchange, including specific, homologous, and substitute, and that further, these compensation types could be differentiated in terms of the need each fulfills and the domain in which the need is manifest. Specific compensation consists of alternative ways of resolving the same need, such as the busy professional who hires a cleaning service. The need for a clean home has been fulfilled, but the coin used has been different (money for service in order to gain time). Homologous compensation is an exchange in which the domain of the resources is the same, but the need that the resource fulfills is different. In the domain of transportation, a homologous exchange might be trading a Porsche for a Prius, where the needs are different (speed versus fuel efficiency). Finally, Pruitt's last classification was that of substitute compensation, where neither the need fulfilled nor the domain is the same. For example, on March 3, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the first effective military draft in the United States. Males between 18 and 45 were to be enrolled in local militias and available for service. Yet draftees could gain an exemption by paying a fee of $300 or by hiring a substitute to take their place. The needs fulfilled by these exchanges were different (national security, personal safety, and using wages to provide for one's family), as was the “coin.”

Yet, as noted by McLean Parks and smith (2006), “the absence of a form of compensation in which both the need and the coin are identical is a glaring omission” (p. 152). Sparrowe et al. (2004) suggested a fourth type of compensation: isomorphic compensation. Isomorphic compensation is when like resources are exchanged that both satisfy the same need, typical of quotidian exchanges such as changing dollars for euros when traveling. Determining the resources for the like-to-like match can be complex, where it is essential to understand the meaning of the resource to the parties themselves from their vantage points. For example, if a dean requests that a faculty member teach an extra course in return for course release the following semester, the exchange would be isomorphic if the extra course represented only the time allocation to the faculty member. But if the overload course prevented the faculty member from attending an important career-enhancing conference, then it is no longer isomorphic.

Pecuniary exchanges, which tend to be monetized and easily compared, may be characterized more easily as utilizing specific compensation, satisfying the same need and exchanged easily across domains. Relational resources, on the other hand, may be more socioemotional and are likely to be particularistic and abstract, thus requiring isomorphic compensation. In the case of ideological currencies, substitutions for addressing the specific needs fulfilled by the ideological currency are unlikely to be satisfactory and to lack isomorphism. This will lead not only to the violation of the psychological contract, but also to disidentification—identifying oneself as not part of the organization—because a sense of identity violation may be the result.

Cross-Cultural Ideological Exchange

We have developed a framework of ideological exchange, including sources of resources and characteristics and attributes of those resources along with their commensurability. Cultures are themselves akin to ideologies, and whereas specific ideologies may have greater or lesser appeal given that culture's values, the idea of ideologies, the elements exchanged, and the sources of those elements in the work relationship, as well as the commensurability of those elements, will apply across cultures. Yet the meaning of different elements and their sources may vary. For example, in collectivist cultures, pay may be simply a pecuniary, economic resource with pay differentials between the top and bottom of the organizational hierarchy minimized. In more individualistic cultures, however, pay may carry with it implicit knowledge of how much one is valued by the organization for their contributions, and hence may confer status and be more relational in focus. In this way, our framework can be generalized across cultures, yet specific ideologies and the meaning conferred by different elements and their sources may be imbued with different meanings and interpretations. In an increasingly global environment, these cultures and associated ideologies may mean that within organizations there are fewer overlapping ideologies. To capitalize on potential benefits of ideological attachment (e.g., Etzioni, 1988; Katz & Kahn, 1966) in exchange relationships, organizations will need to offer more diverse portfolios of ideologically grounded elements to attract a more diverse workforce.

Implications and Conclusions

When organizations assume the mantle of champion for causes valued by workers, the exchange is at least partially based on ideological currency. Organizations can benefit from ideological exchanges, in which contributions by the worker to the organization are likely to take the shape of forms of extra-role activities (e.g., Van Dyne et al., 1995) including organizational citizenship behaviors (e.g., Organ, 1988), where the worker goes beyond role requirements to benefit the organization (when the ideological norms are upheld by the company). However, if violated, these ideological exchanges may result in cases of disaffected workers who engage in organizational deviance (McLean Parks, 1997; McLean Parks & Kidder, 1994; Robinson & Bennett, 1995). Workers whose ideological contract has been violated may withhold effort or engage in sabotage to punish the organization. Thus consequences of reaffirming or disconfirming the ideological elements of the exchange relationship are nontrivial. In this chapter, we have attempted to enrich our understanding of such ideological exchanges and their consequences.

We defined ideological incompatibility as elements that are perceived as logically inconsistent. If logically inconsistent, some elements militate against the ideological cause. If pivotal ideological space is broad (many elements shared), then reactions to the perceived incompatibility perhaps will be more pronounced than if the ideological exchange were not such a large component of the work relationship. In contrast, when the ideological currency is not as pervasive (pivotal space is narrow and shallow), then it is possible that there will be an active and ongoing renegotiation of the exchange through the worker's “rebalancing” of incompatible elements (Festinger, 1957; Heider, 1958), augmenting or discounting the importance of different aspects of the relationship. Which of the incompatibilities will be dismissed or disbelieved will depend on their commensurability and the motivations, expectations, and ideological involvement of the worker (perceiver; Fiske & Taylor, 1991).

Incompatibility provides a motivation to attempt to restore internal equilibrium. Perceivers will resolve minor incompatibility by moderating (Heider, 1958) or discounting (Festinger, 1957) incompatible elements. Yet incompatibility, especially if significant, is unlikely to go unnoticed by the organization, which may generate credible excuses or justifications (Bies & Sitkin, 1991) or attempts to engage in image management (Elsbach, 1994; Gioia & Thomas, 1996) or labeling processes (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1997). Such activities could moderate one or more of the incompatible elements in the perceiver's eyes. Whether or not the incompatible elements are moderated will depend in part on their level of commensurability. If incommensurable, it will be nonnegotiable, potentially severing the relationship. Further, if pivotal space is broad and deep, it is even more likely that the result of incommensurability will be violation of the ideological contract. If these attempts by the organization are regarded as disingenuous, then these effects may be magnified.

In summary, we have examined ideological exchange, articulating the sources of resources that may contribute to the exchange, as well as the characteristics and attributes of those resources and their commensurability. We have identified six sources of resource elements (pecuniary, task, role, relational, occupational, and organizational) that serve as inducements for workers in their ideological exchange with their organization. We acknowledge that the six sources of resource elements we presented are not mutually exclusive and are not exhaustive.

By viewing the content of exchange relationships through the lens of multiple elements, we have identified pivotal ideological space as that which is jointly affirmed by the content of multiple elements. This pivotal space can be characterized in terms of depth and breadth. When pivotal ideological space is maximized in terms of these dimensions, the strength of inducements will be enhanced. Paradoxically, if organizations fail to support the ideology, the contract is violated, and the reaction of the worker in terms of disidentification (e.g., Dukerich et al., 1998; Elsbach & Bhattacharya, 2001) and disaffection (Etzioni, 1988) is likely to be magnified, relative to a violation when the depth and breadth of the ideological space are weaker. Also, we have recognized that there may be an absence of pivotal space or that the content of the elements may be incompatible.

We have extended the concept of crystallization from the literature on organizational culture (Chatman, 1989) and organizational identity (McLean Parks & smith, 2000, 2002) to suggest that when multiple members of an organization hold shared meanings about ideological resource elements and pivotal space, then ideological crystallization occurs. The more crystallized the ideology, the more pervasive it is across workers, and the more they affirm one another's ideological involvement. However, when the ideology is crystallized, if the organization's commitment to the ideology waivers, reactions also will be stronger and more pervasive. Similarly, meta-ideological exchanges may occur when crystallized ideologies lead to spontaneous or planned actions by those who share ideological elements.

Finally, in an ideological exchange, elements range from commensurable to incommensurable, and we expand three types of currency (economic, socioemotional, and ideological) (Pruitt, 1981) and four types of compensation (specific, homologous, substitute, and isomorphic) (Sparrowe et al., 2004) to explain how exchanges are facilitated between the types of resources. Through these currencies and types of compensation, we provided the means through which the process of exchange can occur.

We believe our framework provides a basis from which further research can be developed as scholars continue to refine the construct associated with ideological exchange relationships, enriching our understanding of the work relationship. If work relationships are to be understood more completely, it is imperative that we employ a more nuanced view of the nature and sources of the elements of exchange, and rather than assuming commensurability in resources exchanged, we need to recognize their complexity and richness, as well as the conundrums that complexity presents.

REFERENCES

Allen, V. L., & van de Vliert, E. (1982). A role theoretical perspective on transitional processes. In V. L. Allen & E. van de Vliert (Eds.), Role transitions: Explorations and explanations (pp. 3–18). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Andersen, S. M., & Chen, S. (2002). The relational self: An interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychological Review, 109, 619–645.

Ashforth, B., & Humphrey, R. (1997). The ubiquity and potency of labeling in organizations, Organization Science, 8, 43–58.

Ashforth, B., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14, 20–39.

Biddle, B. J. (1979). Role theory: Expectations, identities, and behaviors. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent development in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12, 1267–1292.

Biemiller, L. (2008). Chronicle of Higher Education. At Washington U., protesters turn their backs on Phyllis Schlafly. Retrieved November 26, 2010, from http://chronicle.com/article/At-Washington-U-Protesters/40987/.

Bies, R. (1987). The predicament of injustice: The management of moral outrage. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 9, pp. 289–319). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Bies, R., & Sitkin, S. (1991). Explanation as legitimation: Excuse making in organizations. In M. McLaughlin, M. Cody, & S. Read (Eds.), Explaining one's self to others: Reason-giving in a social context (pp. 183–198). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bix, B. (1998). Dealing with incommensurability for dessert and desert: Comments on Chapman and Katz. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 146, 1651–1670.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

Caplan, R. (1987). Person-environment fit theory & organizations: Commensurate dimensions, time perspectives and mechanisms, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31, 248–267.

Chatman, J. (1989). Organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Academy of Management Review, 14, 333–349.

Christiansen, C. (1999). Defining lives: Occupation as identity: An essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 547–558.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons.

Crooker, K., smith, f., & Tabak, F. (2002). Creating work-life balance: A model of pluralism across life domains. Human Resource Development Review, 4, 387–419.

Dukerich, J., Kramer, R., & McLean Parks, J. (1998). Identification with organizations: Tales from the dark side. In D. Whetton & P. Godfrey (Eds.), Identity in organizations: Developing theory through conversations (pp. 245–256). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dutton, J., Dukerich, J., & Harquail, C. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263.

Edgeworth, F. Y. (1881). Mathematical psychics: An essay on the application of mathematics to the moral sciences. Charleston, SC: Nabu Press.

Edwards, J., & Cooper, C. (1990). The person-environment fit approach to stress: Recurring problems and some suggested solutions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11, 293–307.

Elsbach, K. (1994). Managing organizational legitimacy in the California cattle industry: The construction and effectiveness of verbal accounts. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 57–88.

Elsbach, K., & Bhattacharya, C. (2001). Defining who you are by what you're not: Organizational disidentification and the National Rifle Association. Organization Science, 12, 393–413.

Engineers Without Borders. (2011). Our story. Retrieved from http://www.ewb-usa.org/about-ewb-usa/our-story

Etzioni, A. (1988). The moral dimension. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Fiske, S., & Taylor, S. (1991). Social cognition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Foa, U. (1971). Intrpersonal and economic resources. Science, 171, 345–351.

Foa, U., & Foa, E. (1975). Resource theory of social exchange. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Gioia, D., & Thomas, J. (1996). Identity, image and issue interpretation: Sensemaking during strategic change in academia. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 370–403.

Gnau, T. (2010). BP employees in Ohio feel weight of Gulf spill. Dayton Daily News, June 9, 2010.

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Goffman, E. (1961). Encounters: Two studies in the sociology of interaction. New York, NY: MacMillan Publishing Co.

Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 83, 1420–1423.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through design of work. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16, 250–279.

Hadefield, G. K. (1998). An expressive theory of contract: From dilemmas to a reconceptualization of rational choice in contract law. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 146, 1235–1285.

Hegel, G. W. F. (1969). The science of logic (A. V. Miller, Trans.). New York, NY: Humanity Books. (Original work published in 1881)

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Jackson, J. (1966). A conceptual and measurement model of norms and roles. Pacific Sociological Review, 9, 35–47.

Kahn, R., Wolfe, D., Quinn, R., Snoek, J., & Rosenthal, R. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. (1966). The social psychology of organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Kidwell, R., Jr., & Bennett, N. (1993). Employee propensity to withhold effort: A conceptual model to intersect three avenues of research. Academy of Management Review, 18, 429–456.

Leiter, B. (1998). Incommensurability: Truth or consequences? University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 146, 1723–1731.

Lessig, L. (1995). The regulation of social meaning. University of Chicago Law Review, 943, 943–1007.

Linton, R. (1936). The study of man. New York, NY: Appleton-Century.

MacNeil, I. R. (1985). Relational contract: What we do and do not know. Wisconsin Law Review, 1985, 483–525.

March, J., & Simon, H. (1958). Organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

McLean Parks, J. (1997). The fourth arm of justice: The art and science of revenge. In R. Lewicki, B. Sheppard, & B. Bies (Eds.), Research on Negotiation in Organization (pp. 113–144). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

McLean Parks, J., & Kidder, D. (1994). Trends: Till death us do part: The changing nature of organizational contracts and commitments. Journal of Organizational Behavior, Trends, 1, 111–136.

McLean Parks, J., Kidder, D., & Gallagher, D. (1998). Fitting square pegs into round holes: Mapping the domain of contingent work arrangements onto the psychological contract, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 697–730.

McLean Parks, J., & Schmedemann, D. (1994). When promises become contracts: Implied contracts and handbook provisions on job security. Human Resources Management, 33, 403–423.

McLean Parks, J., & smith, f. (1998). Organizational contracting: A rational exchange? In J. Halpern & R. Stern (Eds.), Debating rationality: Nonrational aspects of organizational decision making (pp. 168–210). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

McLean Parks, J., & smith, f. (2000, August). Organizational identity: The ongoing puzzle of definition and redefinition. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Meeting, Managerial and Organizational Cognition Division, Toronto, CA.

McLean Parks, J., & smith, f. (2002). Creating organizational identity: The dynamic processes of communication and articulation. Invited paper and presentation, Organizational Identity Conference, Boston, MA.

McLean Parks, J., & smith, f. (2006). Ghost workers: New organizational realities. In P. Taylor & M. Shams (Eds.), Developments in work and organizational psychology: Implications for international business (Vol. 20, pp. 131–162). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, Ltd.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Merton, R. K. (1957). Social theory and social structure. New York, NY: Free Press.

Miller, H. (2004). The frankenfood myth: How protest and politics threaten the biotech revolution. Westport, CN: Praeger.

Morrison, E., & Robinson, S. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22, 226–256.

Nakao, K., & Treas, J. (1994). Updating occupational prestige and socioeconomic scores: How the new measures measure up. Sociological Methodology, 24, 1–72.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company.

Origins. (2010). Origins mission statement. Retrieved November 27, 2010 from http://www.origins.com/customer_service/aboutus.tmpl#/Mission.

Pruitt, D. (1981). Negotiation behavior. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Robinson, S., & Bennett, B. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–572.

Rousseau, D., & McLean Parks, J. (1993). The contracts of individuals and organizations. In L. L. Cummings & B. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 15, pp. 1–43). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Salzman, J., & Rhul, J. (2002). Currencies and the commodification of environmental law. Stanford Law Review, 53, 607–694.

Schein, E. (1980). Organizational psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schmedemann, D., & McLean Parks, J. (1994). Contract formation through employee handbooks: Legal, psychological and empirical analyses. Wake Forest Law Review, 29, 647–718.

Schurman, R. (2004). Fighting frankenfoods: Industry opportunity structures and the efficacy of the anti-biotech movement in Western Europe. Social Problems, 51, 243–268.

Shore, L. M., Tetrick, L. E., Taylor, M. S., Coyle-Shapiro, J., Liden, R., McLean Parks, J., … Van Dyne, L. (2004). The employee-organization relationship: A timely concept in a period of transition. In G. R. Ferris & J. Martocchio (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 291–370). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Simon, B. (2004). Identity in modern society: A social psychological perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Simon, B., Trötschel, R., & Dähne, D. (2008). Identity affirmation and social movement support. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 935–946.

Simpson, B., & Macy, M. (2004). Power, identity & collective action in social exchange. Social Forces, 82, 1373–1409.

Sluss, D. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2007). Relational identity and identification: Defining ourselves through work relationships. Academy of Management Review, 32, 9–32.

Spaeth, J. L. (1979). Vertical differentiation among occupations. American Sociological Review, 44, 746–762.

Sparrowe, R., Dirks, K., Bunderson, S., & McLean Parks, J. (2004). Reinventing the wheel and spinning our wheels: Social exchange and discretionary attitudes and outcomes in organizations. Unpublished manuscript, Washington University at St. Louis.

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 261–302). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Sunstein, C. (1996). On the expressive function of law. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 44, 2021–2053.

Thompson, J., & Bunderson, J. S. (2003). Violations of principle: Ideological currency in the psychological contract. Academy of Management Review, 28, 571–586.

Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & McLean Parks, J. (1995), Extra role behaviors: A critical analysis and theoretical interpretation (a bridge over muddied waters). In B. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 17, pp. 215–285). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

1 These element sources apply to exchange relationships more generally. We are focused on the inducements as idiosyncratically perceived by the worker. For parsimony, we have not included the “contributions” side of the equation, although certainly workers can contribute to organizations through contributions derived from each of these sources as well. For example, the reporter whose story wins a Pulitzer Prize contributes a relational element to the organization in terms of a positive reputation (McLean Parks & smith, 2000, 2002).

2 As noted by Thompson and Bunderson (2003), the ideologies that workers value may or may not be normatively positive, providing the example of targeted hatred as an ideology (e.g., the ideology of organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan).

3 Conjunctive, disjunctive, equivalent, and incompatible elements conceptually parallel set theory; for example, disjunctive (no intersection) with no common elements could be denoted B ∩ C = { }.

4 Depending on their positioning along these two dimensions, Foa and Foa (1975) suggested that resources could be categorized into one of six categories. Although tangential to our discussion, as modified by McLean Parks and smith (1998, p. 131) in an application to transactional/relational exchanges, these categories are standardized exchange units (such as money), tangible goods (such as task outcomes), services (such as tax preparation), information (such as organizational policies), status (such as role or occupational titles), and affiliation (such as friendships).

5 The literature on person–environment fit has addressed commensurability in terms of measurement (e.g., Caplan, 1987; Edwards & Cooper, 1990). For example, Edwards and Cooper (1990) discuss the need for measures of components to be commensurate with theoretical dimensions. Our focus is not on how ideologies are measured, but rather on how individuals perceive resource elements from the various sources to determine the extent to which elements are interchangeable.

6 For exceptions, see McLean Parks (1997), McLean Parks and smith (2006), Pruitt (1981), and Shore et al. (2004).

7 In New Netherland in November 1658, a beaver pelt was equivalent to 16 guilders or 2,240 white or 1,120 black wampum beads.

8 Bix (1998) makes note of the inherent paradox of this view: “it is incommensurability that makes rational choice possible. If all options were reducible to units of some good an individual sought to maximize, there would be no need for ‘choice’…. Any automaton can choose $500, when the alternative is $100; and similarly if one way of life ‘equals’ 5000 ‘units of happiness/contentment’ while an alternative way of life ‘equals’ only 1000 units (p. 1651).”

9 It also may be the case that using utilitarian calculus to rank choices or resources according to a single metric is tantamount to “diminish[ing]” our humanity (Hadefield, 1998). Perhaps less extreme, some lament the monetization of possibly incommensurable resources (Salzman & Rhul, 2000), noting that monetization has adverse effects (Salzman & Rhul, 2000), as actions are imbued with social meaning (Lessig, 1995; Sunstein, 1996). For example, emissions trading can make clean air seem like any other commodity with a price set by the market (Sunstein, 1996).