6

Perceived Organizational

Cruelty: An Expansion of the

Negative Employee–Organization

Relationship Domain

Lynn M. Shore

San Diego State University

Jacqueline A-M. Coyle-Shapiro

London School of Economics & Political Science

Research on the employee–organization relationship (EOR) has primarily drawn upon social exchange theory and the norm of reciprocity (Blau, 1964; Gouldner, 1960) and the inducements–contributions model (March & Simon, 1958) as the bases for describing and categorizing different EORs and their consequences for organizationally desired employee attitudes and behaviors. The key finding emerging from this research supports the contention that social exchange relationships (e.g., perceived organizational support, psychological contract fulfillment, overinvestment and mutual investment employer approaches to the EOR) yield positive benefits for individuals and organizations. An area of the EOR literature that has garnered much less theoretical and empirical attention is negative relationships in which employees perceive that their relationship with the organization is harmful. Two exceptions are psychological contract breach and violation (Robinson, 1996; Rousseau, 1995), consisting of employee perceptions of and emotional reactions to broken promises, and underinvestment and quasi-spot contract using the inducements–contributions employment relationship framework (Tsui, Pearce, Porter, & Tripoli, 1997). In the case of breach and violation, the focus is on lack of organizational fulfillment of promises, a reflection of the norm of reciprocity, and expectations of exchange of favors. In the latter case, the focus is on imbalance of inducements by the organization and contributions by the employee. These literatures provide a starting point for developing a model of negative EORs by highlighting the key roles of reciprocation and balance in establishing and maintaining positive EORs.

Although there is a great deal of research on the deleterious mental, physical, and behavioral effects on employees of abusive treatment in the workplace (Griffin & O'Leary-Kelly, 2004), less attention has been given to the role of the EOR as an intervening variable in situations of mistreatment in contrast to its well-established role in positive organizational treatment (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Zhao, Wayne, Glibkowski, & Bravo, 2007). Favorable organizational and managerial treatment serves as a signal to employees about the degree to which they have a social exchange relationship with the employer, which determines the employee's degree of commitment, turnover intentions, job performance, and citizenship behavior. We argue that current literature does not reflect the most negative kinds of EORs in which employees perceive egregious harm-doing by the organization and its agents. Likewise, limited attention has been given to understanding the situational and psychological mechanisms that link severely harmful organizational treatment to employee perceptions of the EOR. Thus, in this chapter, we develop a model of perceived organizational cruelty (POC) to address this gap in the literature.

We describe the concept of POC and how it differs from established concepts in the negative EOR domain, including psychological contract breach and violation (Montes & Zweig, 2009; Robinson & Brown, 2004) and quid pro quo and underinvestment employment relationships (Tsui et al., 1997). Subsequently, we present a model of antecedents and outcomes of POC and conclude with implications for research, practice, and cross-cultural issues.

DEFINITION OF PERCEIVED ORGANIZATIONAL CRUELTY

To begin our construction of the POC construct, we first considered the many concepts related to mistreatment by organizations that already exist. A very large body of literature has been established on unfair treatment, including topics such as justice and discrimination (Colquitt, 2001; Goldman, Gutek, Stein, & Lewis, 2006; Raver & Nishii, 2010); abusive supervision (Tepper, 2007); and aggression, violence, and victimization (Aquino & Thau, 2009; O'Leary-Kelly, Griffin, & Glew, 1996). In the edited volume The Dark Side of Organizational Behavior (Griffin & O'Leary-Kelly, 2004), two chapters focused on the EOR; specifically, Rousseau's chapter on under-the-table deals, and Robinson and Brown's chapter on breach and violation. Both are noteworthy for discussing the dark side of EOR issues between employees and employers (negative EORs). However, neither focuses on the more extreme negative views that employees may hold about their relationship with the employer—that is, when an employee perceives their employer to be intentionally callous and malicious.

To aid in developing the concept of POC, we first consulted two dictionary sources. Webster's Online Dictionary (n.d.) definition of cruelty is “The attribute or quality of being cruel; a disposition to give unnecessary pain or suffering to others; inhumanity; barbarity.” The Wordnet dictionary (Princeton University, 2010) definition of cruelty is “a cruel act; a deliberate infliction of pain and suffering.” A key aspect of cruelty is the distress experienced. Equally important features are the references to “unnecessary” and “deliberate.” Thus, when organizations treat employees poorly, employees judge the necessity of and the intentions behind such acts (Skarlicki & Folger, 2004). When treatment is perceived as deliberate, unnecessary, and harmful, employees are likely to view the organization as cruel. Thus, we define POC as the employee's perception that the organization holds him or her in contempt, has no respect for him or her personally, and treats him or her in a manner that is intentionally inhumane.

COMPARISON OF POC AND OTHER NEGATIVE EOR CONCEPTS

Although organizations typically consist of multiple agents representing organizational perspectives and interests, the employee often views the organization as a single entity with human-like characteristics. POC involves employee attributions of a “personified” organization. Levinson (1965) was one of the first scholars to point out that employees personify their employing organization. Levinson's (1965) reasoning as to the basis for personification was due to the following aspects of organizations:

(1) The organization is legally, morally, and financially responsible for the actions of its members as organizational agents. (2) The organization has policies which make for great similarity in behavior by agents of the organization at different times and in different geographical locations. (3) These policies are supplemented by precedents, traditions, and informal norms as guides to behavior. (4) In many instances the action by the agent is a role performance with many common characteristics throughout that organization regardless of who carries it out. (pp. 378–379)

These elements of organizations create perceptions among employees of a unified entity with human-like qualities facilitating employees’ characterization of organizations in a manner akin to the characterizations of individuals.

Eisenberger and colleagues (cf. Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, 1986; Eisenberger & Stinglehamber, 2011) built on Levinson's (1965) theorizing to argue that employees have perceptions of organizational support based on inferences that the organization has benevolent or malevolent intentions toward them. Eisenberger and colleagues’ studies of perceived organizational support (POS) have focused on benevolent organizational intentions, whereas the present chapter develops a model of perceived cruelty that spotlights employee perceptions of malevolent organizational intentions. Thus, POC can be considered a mirror opposite of POS in the sense that the organization is viewed as malevolent rather than benevolent, and some of the favorable experiences that contribute to POS (e.g., fair treatment, supervisor support, and investment by the organization; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002) could in a negative form contribute to POC. For example, unfair treatment by the organization, supervisor abuse, or employee investment of time and effort in the organization with no return may all contribute to the development of POC. However, as we will argue later, there are also defining features of POC that are not elements of the POS literature. In particular, the manner in which the agent delivers harmful actions may determine whether the organization is perceived as cruel by the employee.

Psychological Contracts and POC

An important issue is how POC is distinct from other negative EOR constructs such as breach and violation of the psychological contract. Several defining features are central to psychological contracts: (1) they reflect employee perception; (2) they involve a sense of obligation between employee and employer; and (3) they involve ongoing exchange in the EOR (Robinson & Brown, 2004). Breach and violation both refer to situations whereby the employee views an obligation in the psychological contract as unfulfilled. Morrison and Robinson (1997) distinguished breach, the cognitive evaluation that something promised has not been received, from violation, the emotional experience resulting from the interpretation of that breach.

Breach and violation within the psychological contracts literature have a substantially different focus from POC. Whereas psychological contracts center on perceptions of the degree of fulfillment of promises and obligations, POC focuses on the personified employer as a harmful and cruel entity. Breach could be a contributing factor in POC but is likely somewhat distal, because not just any unfulfilled obligation would create such perceptions. Violation, on the other hand, would more likely be associated with POC because it “not only means that one is not getting something one desired or expected but, moreover, that a trusted other betrayed a trust and failed to live up to norms of reciprocity and goodwill that one expects in an ongoing relationship” (Robinson & Brown, 2004, p. 313). Rousseau (1989, p. 129) likewise argued that “violation is an intense reaction of outrage, shock, resentment, and anger, similar to that described by Cahn (1949) in his treatment of injustice. These hot feelings suggest uncontrollability, a quasi-irreversible quality where anger lingers and ‘victims’ experience a changed view of the other party and their interrelationship (Bies, 1987).” Although we expect contract violation to be one contributor to POC, we argue that there are also situational and interpersonal determinants of POC that are outside the bounds of psychological contracts.

The Employment Relationship and POC

The employment relationship model developed by Tsui et al. (1997) also includes negative EOR elements, but ones that are quite different than POC. Their model builds on March and Simon's (1958) framework in which the EOR is viewed as an exchange of organizational inducements for employee contributions. Tsui et al. (1997) outline four types of employment relationships that differ on two dimensions: the degree of balance/imbalance in each party's contributions and whether the focus of these contributions is economic or social. Of relevance here is that a balanced economic exchange (quasi-spot contract) occurs when the employer offers short-term, purely economic inducements in return for highly specified outcomes and the underinvestment approach occurs when the employer expects open-ended commitment and long-term investment from employees in return for short-term economic inducements. In their empirical study, Tsui et al. (1997) found that quasi-spot contracts and underinvestment models were negatively associated with employee attitudes and performance.

Unlike POC, the employment relationship model is based on the exchange offered to groups of employees, either work groups (Hom et al., 2009) or organizations (Song, Tsui, & Law, 2009). The employment relationship model is quite different from POC in that it is focused on the contributions of both parties to the exchange itself, and not on employee perceptions of the personified organization. Thus, although both concepts are within the EOR domain, Tsui's model is less personal and specific to the employee, and unlike POC, it does not focus on individual employee perceptions of intentional organizational harm-doing. Rather, the employment relationship spotlights the nature of the exchange itself as balanced or unbalanced and as economic or social. The underinvestment and quasi-spot contract employment relationships may contribute to POC by creating a setting in which poor organizational treatment is more likely.

Psychological Mechanisms Underlying POC

The psychological contract and POS literatures are based on social exchange theory and the norm of reciprocity (Blau, 1964; Gouldner, 1960), and both of these concepts, along with POC, are perceptual in nature. This raises questions as to the role of norm of reciprocity in relation to POC. Gouldner (1960) argued that “a norm of reciprocity, in its universal form, makes two interrelated, minimal demands: (1) people should help those who have helped them, and (2) people should not injure those who have helped them” (p. 171). According to Norm Violation Theory (DeRidder & Tripathi, 1992), norms serve to sanction the actions of group members, and it is assumed that these norms are commonly known and followed. When violated, such actions are viewed as illegitimate and inspire sanctions for noncompliance as a means to enforce norms and ensure future compliance. In the case of the EOR, employees may be less likely to apply sanctions for noncompliance to the norm of reciprocity given their likely greater dependence on the organization (Shore & Shore, 1995) and fear of reprisals. This creates a dilemma for employees of how best to respond to nonreciprocity from the organization.

Research on the employment relationship model (Tsui et al., 1997) provides evidence that employees prefer and seek balance in the exchange of inducements and contributions with the employer, as shown by the superiority of the mutual investment as compared with the underinvestment model (Hom et al., 2009). Thus, when an employee perceives that she is underrewarded relative to her efforts, she may be challenged as to how to restore a sense of balance, especially if she is not very marketable. Research by Siegrist (1996) provides support that such imbalance is harmful to the employee's health. His Model of Effort–Reward Imbalance at Work proposes that employees compare their efforts and rewards, and if they are in a high cost/low gain condition, this creates a situation of high stress. Recent research on his model showed that “the risk of incident stress-related disease, such as coronary heart disease or depression, is about twice as high in men and women scoring high on effort-reward imbalance compared to non-exposed people” (Siegrist, 2009, p. 305). Thus, in addition to being viewed as unfair and counternormative, an unbalanced EOR challenges the employee's health and well-being.

Disregard of reciprocation by the organization is likely to lead to a loss of trust in the organization and fear of future nonreciprocation. Taking ill treatment a step further, a malevolent and injurious organization is operating in an antinormative manner when directly harming an employee who is helpful to the organization. How might such detrimental treatment be dealt with by the employee? Employees who espouse the negative reciprocity norm, the belief that retaliation, or an “eye for an eye,” is an appropriate response to wrongdoing (Eisenberger, Lynch, Aselage, & Rohdieck, 2004), may comfortably act in ways that restore balance in the exchange with the employer when faced with POC by directly harming the organization. By comparison, employees who do not believe in negative reciprocity may be more conflicted as to how best to restore balance in the exchange so that they do not feel victimized by such treatment. Retaliatory behavior can cause employee feelings of guilt, anxiety, and stress (Skarlicki & Folger, 2004), and this may be especially likely for those who are highly conscientious or who would normally frown upon such behavior. Self-regulation impairment may be another reason why abused employees retaliate. That is, the experience of abuse undermines the employee's ability to regulate their own behavior by depleting their emotional resources (Thau & Mitchell, 2010). As argued by Thau and Mitchell (2010), “The experience of abuse challenges victims to process, interpret, and understand the causes and consequences of being harmed” (pp. 1009–1010).

In sum, a key principal that underlies both positive and negative EORs is balance in exchange. Although social exchange and the norm of reciprocity provide a basis for predicting employee attitudinal and behavioral responses when the EOR ranges from neutral to positive, when the EOR is negative due to nonreciprocation by the organization or involves more actively harmful treatment of the employee, other types of norms as well as psychological processes, such as the negative reciprocity norm or self-regulation impairment, may operate. When organizational agents engage in antinormative behavior, employees are challenged as to how to respond given their lesser power and the risks associated with engaging in aggressive actions or with passively accepting ill treatment in light of the negative health consequences. Employees who do not believe in the negative reciprocity norm or fear the consequences of acting in a retaliatory manner will still seek ways to create balance in the exchange, such as through actively seeking ways to create or reinstate a positive relationship (e.g., voicing concerns, asking for changes, or engaging in influence tactics such as ingratiation) or through more subtle harmful behavior (e.g., gossiping, extended breaks). If the stress of being victimized is too great, some employees will behave in ways considered inappropriate (e.g., losing their temper, behaving unprofessionally), which may further enable the transgressor to justify the ill treatment. Employees who view the relationship as irretrievably broken will likely seek jobs outside the current employer or suffer either emotionally or by engaging in self-destructive behavior if changing jobs is not a possibility.

A MODEL OF POC

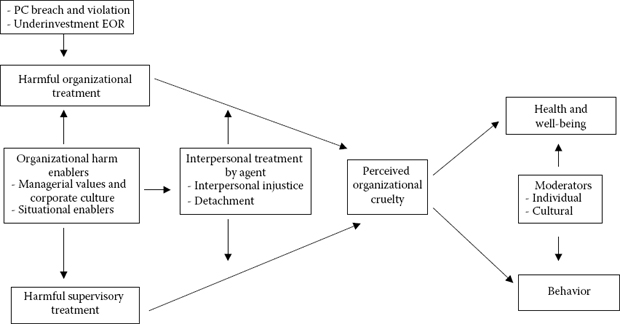

Our model depicted in Figure 6.1 is an early-stage model of antecedents and outcomes that is intended to guide future empirical research on POC. Unlike models of malevolent supervisors (cf. Tepper, 2000) that focus on acts of single individuals, we argue that POC is based on employee perceptions of the participation, either direct or indirect, of multiple organizational agents. Unethical acts within organizations often involve knowing cooperation among numerous employees (Anand, Ashforth, & Joshi, 2005). When managers in positions of power engage in malevolent acts toward individual employees or toward groups of employees, these acts may in fact be viewed as reasonable either because of a business justification or because the recipient(s) may be seen as deserving mistreatment due to their own behavior (Scott, Colquitt, & Paddock, 2009). Such complicit behavior is likely to increase the frequency of harmful acts and the ease of individuals in observing or engaging in destructive treatment of others. Thus, a critical element of POC is the inference by the employee that the organization is involved in his or her mistreatment.

FIGURE 6.1

Model of perceived organizational cruelty. PC, psychological contract.

ANTECEDENTS OF POC

We propose that organizational practices deemed to be harmful to the individual and persistent exposure to negative managerial behaviors are likely to lead to the perception that the organization is a cruel one. Although many types of organizational and supervisory treatment could be considered harmful by employees, they may not lead to perceptions of organizational cruelty. Acts deemed to be cruel require organizational conditions that facilitate a level of mistreatment that is perceived as intentionally harmful. We refer to these conditions as “organizational harm enablers,” including corporate culture and managerial values, along with organizational processes that increase the likelihood that transgressors do not take personal responsibility for harm-doing, such as legitimizing harm, initial small acts of minor harm-doing, and displaced responsibility. In addition, as part of the sensemaking process, targets of harm assess the degree of organizational cruelty by making attributions of the responsibility, intentionality, and justification for the harm, and also by considering the interpersonal treatment associated with the destructive event. The enactment of organizational harm and its delivery, coupled with an individual's sensemaking of the harmful treatment, are likely to lead to an evaluation that the organization is cruel.

Organizational Harm Enablers

Corporate Culture and Managerial Values as Enablers

Kanter (1987) argued that “Symbols are an important part of organizational culture, and they can send positive or negative messages” (p. 23). The actions of organizational leaders are scrutinized by employees as they seek to understand the culture of their organization. Fraud, insider trading, and giving executives bonuses while employees are getting laid off would all be examples of organizational actions that provide a negative message to employees about the values of their leaders. Such negative symbolic acts may also increase the likelihood that other destructive behaviors involving mistreatment of employees may be allowed or even condoned.

There are a number of ways in which organizations can portray a negative regard for employees’ contributions and a disregard for their well-being. Exploitive and cruel practices that are enacted by destructive leaders are in all likelihood a reflection of the values of top management. Destructive leadership assumes that the leader's intentions are bad and certain behaviors are inherently vicious (Padilla, Hogan, & Kaiser, 2007). However, Kellerman (2004) contends that negative leader behaviors can include both incompetence and evil behaviors, and it is the latter that is of relevance here. Zimbardo (2004) defines evil as “intentionally behaving—or causing others to act—in ways that demean, dehumanize, harm, destroy, or kill innocent people” (p. 3). Padilla et al. (2007) argue that destructive leadership may be based on an ideology of hate. This type of leadership can also be seen in the case of Enron, where leaders created a culture of intimidation. For example, chief financial officer (CFO) Andrew Fastow had a desk cube with the inscription “When ENRON says it's going to ‘rip your face off’ … it means it will rip your face off” (Raghavan, 2002, p. A1, cited in Padilla et al., 2007). Although a drastic symbolic act, the inscription signals a disregard for the well-being of employees through managerial coercion and dominance. Consequently, we would expect that the presence of destructive leadership at the top of organizations will increase the likelihood of organizational practices and policies that employees deem as abusive.

Nishii, Lepak, and Schneider (2008) argued that human resource (HR) practices motivated by a management philosophy based on exploitation or getting the most out of employees would be negatively associated with employee attitudes. Empirically, the authors found that employee attributions of HR practices reflecting a managerial philosophy focused on employee exploitation were negatively related to employee commitment and satisfaction. This is similar to what Storey (1992, p. 26) terms a hard utilitarian approach that views employees as a resource that management should exploit to the fullest and places little value on the concerns of workers. Likewise, we anticipate that employees would perceive the practices implemented as part of a cost-reduction strategy to be potentially exploitative and hence harmful to their needs. Drago (1996) found the effects of high-performance practices for workers to be negative in what was termed “disposable work-places” where workers were coerced to cooperate because the employer had the power to relocate.

Situational Enablers

Although destructive leadership may at times be intentional, at other times it may be due to elements of the organizational context. Managers who behave ethically in most of their life spheres (e.g., family, community) may nonetheless, within a particular organizational context, behave in corrupt and harmful ways. O'Leary-Kelly et al. (1996) argued that social learning is one reason for harmful behavior. Specifically, when organizational leaders do not punish aggression but rather reward individuals who engage in the behavior, or model the behaviors themselves, employees may increasingly engage in such behavior.

Milgram's studies (1974) on obedience to authority make clear the importance of organizational environments in creating conditions for harmful treatment. Using authority to legitimize the actions, disguising the harmful treatment as somehow appropriate or even helpful, escalating harmful acts by increasing their destructiveness gradually, displacing responsibility for harm to authority figures, and dehumanizing labels and stereotypes of potential victims all increase the likelihood that individuals will engage in harmful treatment of others (Zimbardo, 2000).

Anand et al. (2005) argue that harmful actions in organizations are facilitated by rationalization tactics such as denial of responsibility, denial of injury to the victim, and economic pressures. Likewise, employees can be socialized to accept corrupt practices through rewards and acts of compromise that appear to solve pressing organizational problems but that eventually cause them to “back into” corrupt behavior. As harmful treatment of employees becomes more common, such actions become part of the fabric of the organizational culture through a set of organizational norms.

Harmful Supervisory Treatment

Although harmful practices are likely to be primarily determined by actions and decisions made by upper management as described earlier in terms of organizational enablers, we expect that supervisory treatment will also be important in creating perceptions of POC. The supervisor, as an agent of the organization, is viewed as representing the organization in most interactions with their direct reports (Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, 2007). As such, a supervisor who is perceived as behaving in an intentionally harmful manner will likely contribute to POC.

There are a number of existing constructs that capture supervisory negative behavior toward employees including abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000), hierarchical abuse of power (Vredenburgh & Brender, 1998), petty tyranny (Ashforth, 1997), supervisor aggression (Schat, Frone, & Kelloway, 2006), and supervisor undermining (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, 2002). Tepper (2000, p. 178) defines abusive supervision as “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and non verbal behaviors, excluding physical contact.” Sharing some conceptual ground, Ashforth (1997, p. 126) defines petty tyranny as the superior's use of power “oppressively, capriciously, and perhaps vindictively.” These constructs capture a range of negative behaviors that may or may not be intended to cause harm to the recipient. For example, Tepper's (2000) definition of abusive supervision suggests that supervisors may engage in those behaviors not to cause harm but rather to achieve some other goal such as higher performance, whereas supervisor aggression specifically refers to the intention to cause harm. Putting aside the intention behind such behaviors, all these definitions involve a supervisor “including” the employee in negative interactions.

However, exclusion may be even more damaging from the employee's viewpoint. Ostracism captures the degree to which an individual perceives that he or she is ignored or excluded by others (Williams, 2001) and represents a form of “social death” (Sommer, Williams, Ciarocco, & Baumeister, 2001) because it gives the individual an experience of what it is like not to exist. Social exclusion has been shown to result in harmful cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and health outcomes (Baumeister, DeWall, Ciarocco, & Twenge, 2005; Blackhart, Nelson, Knowles, & Baumeister, 2009; DeWall, Maner, & Rouby, 2009). This form of negative behavior is different from abusive behaviors because despite the aversive nature of such acts on the recipient, there is an acknowledgment through the negative interactions that the recipient exists. According to Williams (2001), long-term targets of ostracism suggested that they would prefer to have verbal or physical abuse than be ostracized.

Employee Sensemaking of Harmful Treatment

Although most harmful treatment occurs at an interpersonal level (supervisor to subordinate), we argue that these actions will in many instances be viewed as reflecting the organization's actions rather than as a result of an organizational agent acting simply as an individual. As Eisenberger and Stinglhamber (2011, p. 41) note, “employees at various levels in the organizational hierarchy tend to experience the organization as a unitary force whether benevolent or malevolent.” Such malevolent actions by the supervisor will be interpreted by employees as reflecting the organization's negative evaluation of them. This is more likely to hold true when an individual perceives the supervisor as embodying the values of the organization (referred to as supervisor organizational embodiment), when employees attribute the behavior to the purposeful intentionality of the supervisor, and when it is within the supervisor's control (Stinglhamber & Vandenberghe, 2004). If the employee feels he or she has been singled out for harmful treatment, this represents a personalized form of malevolent treatment and so will be particularly impactful on employee perceptions of organizational cruelty.

Employees’ attribution of responsibility for supervisory mistreatment will also affect whether they perceive the organization as a cruel entity. A central premise of attribution of responsibility is that an entity can be held accountable for an event. Heider (1958) argued that attributions involve judgments regarding the responsibility of the entity versus that of the environment, resulting in three attributions: (1) intentionality, indicating the extent to which the outcome is a deliberate action by the organization—in this situation, the extent to which the organization hired and promoted the supervisor and gave the supervisor free rein to act malevolently with employees; (2) foreseeability, indicating the extent to which the organization is held accountable because it should have anticipated the actions of the supervisor; and (3 justifiability, indicating the extent to which the organization's actions are justifiable. Employee attributions of intentionality and foreseeability are likely to strengthen the relationship between negative supervisory behavior and POC, whereas attributions of justifiability are likely to weaken that relationship.

Another way in which employees determine whether the organization is cruel is by the interpersonal treatment they receive when a harmful action is being administered by an organizational agent. There are several forms of interpersonal treatment that are likely to increase employee perceptions of organizational cruelty, including lack of interactional justice and psychological disengagement. Callous, unethical, or disrespectful behavior directed at an employee by a supervisor or another organizational agent generates strong feelings of anger because such treatment signals how little the employee is valued and respected by the organization (Bies, 2001). Thus, harmful treatment that is lacking in interactional justice increases POC. In addition, the employee is more likely to perceive that the organization is cruel when the agent appears to be psychologically disengaged from the harm that they are inflicting (Folger & Pugh, 2002). A study by Clair and Dufresne (2004) showed that employees who administered layoff decisions used humor, depersonalization of the victim, and avoidance of personal contact with layoff victims to psychologically disengage. In a qualitative study by Margolis and Molinksy (2008) on “necessary evils” (i.e., harmful acts required by an individual's work role, such as layoffs and firing), disengagement was reflected in several ways: “(1) denial of any experience of prosocial emotion; (2) active dissociation from the target's experience, through dehumanizing the target or minimizing the task's negative impact; or (3) dehumanizing the self through either deindividuation or attribution of one's personal actions to the role, job or organization rather than to one's private, personal agency” (p. 853). In sum, the manner in which the agent delivers the harmful treatment to the employee will also determine whether the employee perceives the organization as cruel.

OUTCOMES OF POC

Employees are likely to respond in a number of ways to perceiving the organization as cruel, and we focus on two categories of responses: employee health and well-being and behaviors.

Health and Well-Being

Treating individuals in an inhumane and cruel way is a violation of their dignity and self-respect, and this is likely to invoke stress-related reactions. Therefore, POC is likely to be positively associated with metabolic syndrome (a cluster of synergistic risk factors predictive of heart disease/diabetes), stress, anxiety, and depression. Siegrist (2009) reviewed 12 prospective epidemiological studies and showed support for the health-adverse effects (e.g., coronary heart disease, depression, type 2 diabetes) of effort–reward imbalance at work due to potential damage to an individual's self-esteem as a result of failed reciprocity. De Vogli, Brunner, and Marmot (2007) found that self-reported unfairness predicted metabolic syndrome and its components (waist circumference, serum triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, fasting serum glucose, and blood pressure). The authors speculated that frequent experiences of unfair treatment may produce psychological distress in the form of inward-focused or outward-focused emotions dependent on the attributions for injustice. Inward-focused emotions may include feeling devalued, which can lead to anxiety and depression, whereas outward-focused emotions such as anger and hostility occur when blame is externalized. Likewise, MacDonald and Leary (2005) argue that social pain defined as “an emotional reaction to the perception that one is excluded from desired relationships or being devalued by desired relationship partners or groups” (p. 202) may contribute to pain-related disorders. This body of work suggests that unfairness, failed reciprocity, and devaluation of the relationship have adverse consequences for an individual's physical heath.

Individuals are also likely to experience fear and anger when perceiving that their relationship with the organization is a cruel one. Acts of perceived cruelty could trigger what Kane and Montegomery (1998) call disempowerment, defined “as a process whereby a work event or episode is evaluated by the individual as an affront to his/her dignity; hence a violation of a fundamental norm of consideration and respect” (p. 264). The authors also argue that there is likely to be a strong cumulative effect if allowed to amass over time. Employees who perceive their organization as cruel are likely to experience fear in speaking up about the treatment received. In particular, “quiescent” silence (Pinder & Harlos, 2001) captures the withholding of verbal comments due to the anticipation of negative consequences for the individual. Kish-Gephart, Detert, Trevino, and Edmondson (2009) argue that fear of authority is a prepared fear that helps explain the pervasiveness of silence at work as speaking up risks angering those in higher status, which could lead to negative ramifications.

The feeling of anger that is “associated with the sense that the self (or someone the self cares about) has been offended or injured” (Lerner & Tiedens, 2006, p. 117) is liable to be triggered by experiences such as public humiliation, disrespectful or unjust treatment, or violation of moral standards (Bies & Moag, 1986; Cropanzano, Goldman, & Folger, 2003; Harlos & Pinder, 2000). The nature of employees’ anger is likely to be both inward focused and outward focused, with the former directed at the self for acquiescing to a harmful relationship with the employer and the latter directed at the source of the harmful treatment. Kish-Gephart et al. (2009) note that anger and fear may occur simultaneously in reaction to the same event, whereby the intensity of each may influence whether silence or voice is enacted.

In view of the empirical evidence, we argue that POC will have adverse effects on an individual's health and well-being. Being in a relationship with a destructive and demeaning organization is likely to invoke perceptions of relational devaluation and unfairness and is also likely to thwart an individual's basic needs. The violation of justice norms and needs of self-esteem, belonging, control, and meaningful existence as a result of organizational cruelty may explain the resultant effects on employee health and well-being.

Behavior

Behavioral responses to POC can be categorized as passive, such as silence, learned helplessness, and neglect, or as active, including retaliation and exit. Silence is multidimensional, and of relevance here is acquiescent silence, which is the withholding of relevant ideas, information, or opinions based on resignation—disengaged behavior (Van Dyne, Ang, & Botero, 2003). Acquiescent silence is passive and uninvolved behavior; employees “are resigned to the current situation and are not willing to exert the effort to speak up, get involved, or attempt to change the situation” (Van Dyne et al., 2003, p. 1366). Pinder and Harlos (2001) focused on employee silence as a response to injustice, and similar arguments could be made in terms of employee responses to POC.

Learned helplessness “is the notion that after repeated punishment or failure, persons become passive and remain so even after environmental changes that make success possible” (Martinko & Gardner, 1982, p. 196). An attributional framework was incorporated into learned helplessness theory to explain the link between noncontingent reinforcement situations and the expectation of future noncontingency (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). The two attributional dimensions capture internal/external and stable/unstable—the degree to which individuals attribute causes to themselves, to others, or to circumstances, and the extent to which individuals attribute causes to a temporary or permanent event (Weiner, 1972). These attributions help predict when individuals will experience helplessness; specifically, when individuals attribute the experience of organizational cruelty to themselves (e.g., because they are not worthy) and when they view the cause as stable (the organization's cruelty is enduring or recurrent), employees are more likely to experience helplessness.

Neglect refers to “passively allowing conditions to deteriorate through reduced interest or effort, chronic lateness or absences, using company time for personal business or increased error rate” (Rusbult, Farrell, Rogers, & Mainous, 1988, p. 601). The authors argue that neglect can capture very passive responses, such as reduced interest, and also reactions that are moderately passive, such as intentionally missing work. Employees in relationships deemed as cruel are likely to have low investment in that relationship given the lack of resources they receive and hence engage in neglect as a response to such treatment. Rusbult et al. (1988) speculate that there may be a temporal element to how individuals respond, and drawing on this, we speculate that neglect may be a temporary response progressing to exit in the longer term.

Individuals may also engage in active responses such as retaliation or exiting the organization. Although there are a number of terms used to reflect negative employee behaviors, Skarlicki and Folger (1997) argue that the term retaliation has less of a pejorative connotation than deviance, and whereas deviance presumes wrongful and negative employee conduct, retaliation can be a legitimate response to mistreatment by managers. In view of the perceived purposeful intention of organizational cruelty as we have defined it, retaliation seems a probable employee response.

There is considerable empirical support for the contention that when employees are mistreated, they respond in a negative way (Aquino, Tripp, & Bies, 1998; Mitchell & Ambrose, 2007; Skarlicki & Folger, 1997). Hollinger and Clark (1983) reported that employees who felt exploited by the organization engaged in acts of theft as a way of correcting the injustice. Two explanations may explain this: restoration of justice and reestablishment of personal control. Gouldner's (1960) negative norm of reciprocity explains why individuals who feel mistreated are motivated to retaliate (an eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth), and according to Bies and Tripp (2001), this negative reciprocity can restore a sense of justice. In addition, Mitchell and Ambrose (2007), drawing on reactance theory, argue that retaliation can restore an individual's sense of control following harmful treatment.

In the social psychology literature, rejection is defined as being excluded from or being devalued by a desired person, group, or relationship (MacDonald & Leary, 2005). POC is a form of rejection in that it signifies a devaluation of the employee and is likely to lead to intentions to leave and turnover. Empirical evidence found that participants rejected by their workgroup were less likely to want to remain with the organization than accepted participants (Hiltan, Kelly, Schepman, Schneider, & Zarate, 2006). Rejection by organizational agents is likely to violate belongingness needs as well as norms of fair treatment and thus motivate an employee to leave the relationship with the organization if at all possible.

MODERATORS

Individual

Although there are potentially numerous moderators that come into play in terms of understanding how individuals respond to POC, we focus on three moderators that have a relational focus: hardiness, dependence, and the employee's belief in the negative norm of reciprocity. Hardiness describes an individual's predisposition to be “resistant to the harmful effects of stressors and effectively adapt and cope with a demanding environment” (Eschleman, Bowling, & Alarcon, 2010, p. 277). It is a multidimensional construct consisting of commitment, control, and challenge. Commitment captures the extent to which an individual is engaged in a variety of life domains and results in the development of social relationships that can act as social support. Control reflects the extent to which an individual believes that he or she can control events and challenge the extent to which difficult situations are seen as challenges or threats (Eschleman et al., 2010). Hardiness has been found to moderate the relationship between stressors and strains by acting as a buffer (Kobasa, 1979), and a recent meta-analysis (Eschleman et al., 2010) provides support for the moderating effect of hardiness: Hardy individuals experience less strain in the presence of stressors than less hardy individuals. We would expect hardy individuals to respond less negatively to POC in terms of anxiety, depression, and stress due to the buffering effect of social support provided by their commitment to a number of life domains. Because hardy individuals have a greater perception of control over their environment, they will be more likely to engage in active responses such as retaliation and exit in response to POC than silence, learned helplessness, and neglect, as the former responses allow the individual to proactively control his or her environment. The challenge subfacet of hardiness is likely to influence an employee's emotional response in terms of diminishing the likelihood of fear of speaking up because the employee would interpret the situation as a challenge rather than a threat.

The extent to which an individual reacts passively or actively depends on the individual's perceived dependence/power imbalance in their relationship with the organization. Rusbult and Van Lange (2003) define dependence situations as those involving “need” or “reliance on” another (p. 363). The authors argue that dependence explains why individuals remain in abusive relationships and endure continuing abuse when they are relatively dependent—high investments and poor alternatives. Molm (1988) argues that in relationships that are characterized by power imbalance, the weaker party is dependent on the more powerful for resources. The more dependent one party is on the other, the more constrained they will be to act in ways that serve their interests. As a result, highly dependent employees who have imbalanced or harmful EORs will view engaging in acts of retaliation as too risky because these acts might provoke the threat of further harmful organizational treatment. Silence is a more probable response due to their dependency on the organization. Conversely, individuals with low dependency might be more likely to engage in retaliation or leave the organization because they will have viable alternatives.

The extent to which individuals subscribe to negative norms of reciprocity is likely to influence the extent to which they respond outwardly to the source of the cruelty. Eisenberger et al. (2004) found that individuals who more strongly endorsed negative reciprocity were more likely to engage in retribution following unfavorable treatment. Mitchell and Ambrose (2007) found that negative reciprocity beliefs moderated the relationship between abusive supervision and deviance directed at the supervisor such that it was stronger for those who endorsed negative reciprocity compared to those who did not. Therefore, we would expect employees who more strongly endorse negative reciprocity beliefs to engage in quid pro quo behaviors directed at the organization (i.e., neglect, retaliation, and exit) following an evaluation that the organization is cruel.

Cultural Influences

Drawing on Hofstede's (1980) work on cultural values, we argue that two cultural values, power distance and masculinity–femininity, are likely to affect how individuals respond to POC. Whereas Hofstede (1980) argued that these cultural values are meaningful at the societal level, Kirkman, Lowe, and Gibson (2006) found that more studies examined cultural values at the individual level than at the societal level, and Clugston, Howell, and Dorfman (2000) found that Hofstede's cultural dimensions capture large variation across individuals in society. We recognize that although cultural values vary across the societal level, there will be variation within a particular society regarding the extent to which individuals subscribe to those values.

Power distance captures “the extent to which a society accepts the fact that power in institutions and organizations is distributed unequally” (Hofstede, 1980, p. 45). Waldman et al. (2006) found that high-level managers in high–power distance cultures are “more self-centered or lacking in concern for shareholders/owners, broader stakeholder groups, and the community/society as a whole…. thus, in such societies, there may be more tendencies toward the manipulative use of power” (p. 834). This suggests that high–power distance managers may be less attuned to the occurrence of the kind of treatment that may be associated with POC within their organization and that there may be greater tolerance for harmful treatment of employees when high-level managers engage in this behavior. Furthermore, as Farh, Hackett, and Liang (2007) argue, employees high on power distance are deferential to authority figures and display respect, loyalty, and dutifulness due to their conformance to role expectations. Thus, in high–power distance cultures, it is unlikely that employees would respond actively (by engaging in retaliation or exit) because this would be seen as a challenge to authority. Managers in high–power distance cultures are more likely to endorse conformity among subordinates and will be less tolerant of variability, suggesting subordinate neglect is unlikely to be tolerated. Given the deferential relationship with authority figures expected in high–power distance cultures, engaging in neglect is likely to create cognitive dissonance in the subordinate and therefore an unlikely response to POC. We anticipate that employees in high–power distance cultures are more likely to adopt silence in response to POC because this would be consistent with the value attached to conformity and hierarchy. On the contrary, individuals in low–power distance cultures are more likely to engage in neglect, retaliation, and exit in response to POC contingent upon an individual's dependence with the organization.

Masculinity–femininity values capture the extent to which the culture emphasizes values of assertiveness, ambition, aggression, achievement orientation, and competitiveness (masculine) or values of quality of life, interpersonal relationships, and concern for the weak (feminine; Hofstede, 1980). We speculate that employees in high-masculine cultures will respond more actively to POC and those in high-feminine cultures will respond more passively. The emphasis on ambition and achievement orientation is likely to promote an individual's self-interest, whereas assertiveness and aggression are likely to provoke action toward resolving the situation to further an individual's self-interest. In view of this, employees in highly masculine cultures may be more likely to engage in retaliation and exit the organization in response to POC. In feminine cultures, the emphasis on benevolence (Gordon, 1976) may translate into doing things for others and being generous, and this might involve a degree of self-sacrifice. Given the emphasis on “what is given to a relationship,” employees may be more accepting of being party to a cruel relationship, provoking silence as a response.

Research by Dorfman et al. (1997) comparing leadership behavior cross-culturally (United States, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and Mexico) also has implications for our model of POC. Specifically, whereas supportive, contingent reward, and charismatic leadership behavior had universally positive effects, directive, participative, and contingent punishment behavior had differential effects across cultures. For example, contingent punishment where managers provided negative feedback in response to poor performance “had a completely desirable effect only in the United States, but equivocal or undesirable effects in other countries” (Dorfman et al., 1997, p. 262). This implies that perceptions of organizational cruelty may be precipitated by varied managerial behaviors in different cultural settings, suggesting the need for future cross-cultural research.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Considerable research has been conducted on the positive EOR, yet few scholars have sought to develop the negative EOR domain. In this chapter, we set forth a new concept of POC, including antecedents and outcomes. As yet, it is unclear how common such perceptions are and the potential long-term impact POC may have. We suspect, in light of the burgeoning literature on workplace aggression and victimization (Aquino & Thau, 2009), that POC might occur more frequently than would be expected at first glance. However, going forward, an important starting point would be to determine the base rate for POC in normally functioning organizations. Although breach of the psychological contract has been established as common (cf. Robinson, 1996), we would expect the more extreme treatment reflected in perceptions of organizational cruelty to be less frequent than breach. Yet, we anticipate that POC would have a much stronger impact on employees’ well-being than has been observed with psychological contract breach or with underinvestment employment relationships.

Thus far, research on workplace aggression and victimization has not studied the harmful impact of such treatment on employee perceptions of the EOR, but rather has focused on the buffering effect of positive employment relationships on demanding or taxing work settings. For example, there is evidence that POS can have a buffering effect on workplace stresses (George, Reed, Ballard, Colin, & Fielding, 1993). Our model suggests that at the other end of the EOR continuum, POC is likely to interfere with the employee's ability to cope with stressful work environments by adding to the employee's stress load. POC may be particularly harmful in light of the negative effects on emotions, by undermining the recipient's ability to maintain positive relations with coworkers who might normally provide the social support that would buffer workplace strains (Aquino & Thau, 2009). Even if social support is forthcoming, POC may also weaken the individual's ability to reciprocate because of stress created by high levels of POC. In fact, Nahum-Shani and Bamberger (2011) showed that social support may actually increase stress if the recipient cannot return the favor (underreciprocating). Specifically, they argue that social support that cannot be reciprocated is a violation of reciprocity norms, resulting in a negative self-image and a weaker sense of control over the situation. Exceedingly harmful treatment leading to high levels of POC may decrease the individual's ability to maintain positive workplace relations including repaying social support, which may have a knock-on effect on their capacity to cope.

Models of workplace aggression have not incorporated employee perceptions of the employment relationship that result from such treatment. We view this as an important omission in the literature, especially because there is overwhelming evidence that employees interpret organizational treatment in relational terms and respond accordingly (Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, 2011). Going forward, it will be important to understand the environmental challenges that increase the likelihood of POC. In a globally competitive economy, POC may be more common as companies seek to deal with the associated economic challenges by expecting employees to work longer hours and take on more responsibilities, particularly in tight labor markets where employees may be viewed as more replaceable but themselves are less able to exit. In addition, future research needs to focus on factors that increase the likelihood that managers create high levels of POC beyond those identified in this chapter. We argued for the important role of situations for creating conditions that precipitate organizational cruelty, but it is also possible that individual differences among organizational founders and leaders set the stage for cruel employee treatment. For example, narcissism has been associated with amorality as shown by the lack of hesitation of narcissistic leaders to commit violent and gruesome acts (Horowitz & Arthur, 1988).

This chapter provides a model of POC and supplies some evidence of links that can be made between the workplace aggression literature and the EOR literature. Illustrating these links can provide a useful new lens for understanding negative EORs and for further development of the workplace aggression literature. Employee sensemaking of harmful treatment as reflecting the EOR and associated employee responses have important implications for the development, maintenance, and dissolution of employment relationships. This chapter establishes the connections between organizational and managerial mistreatment, POC, and emotional and behavioral outcomes, but the task of empirical testing and refinement of these ideas is needed to fully understand the negative EOR domain.

REFERENCES

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E. P., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74.

Anand, V., Ashforth, B. E., & Joshi, M. (2005). Business as usual: The acceptance and perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 9–23.

Aquino, K., & Thau, S. (2009). Workplace victimization: Aggression from the target's perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 717–741.

Aquino, K., Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2006). Getting even or moving on? Power, procedural justice, and types of offense as predictors of revenge, forgiveness, reconciliation and avoidance in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 653–668.

Ashforth, B. E. (1997). Petty tyranny in organizations: A preliminary examination of antecedents and consequences. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 14, 126–140.

Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 589–604.

Bies, R. J. (1987). The predicament of injustice: The management of moral outrage. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Shaw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 289–319). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Bies, R. J. (2001). Interactional justice: The sacred and the profane. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 89–115). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. F. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negotiations in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43–55). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Bies, R. J., & Tripp, T. M. (2001). A passion for justice: The rationality and morality of revenge. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: From theory to practice (Vol. 2, pp. 197–208). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Blackhart, G. C., Nelson, B. C., Knowles, M. L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2009). Rejection elicits emotional reactions but neither causes immediate distress nor lowers self-esteem: A meta-analytic review of 192 studies on social exclusion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13, 269–309.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Clair, J. A., & Dufresne, R. L. (2004). Playing the grim reaper: How employees experience carrying out a downsizing. Human Relations, 57, 1597–1625.

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., & Dorfman, P. W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? Journal of Management, 26, 5–30.

Colquitt, J. A. (2001). On the dimensionality of organizational justice: A construct validation of a measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 386–400.

Coyle-Shapiro, A.-M., & Shore, L. M. (2007). The employee-organization relationship: Where do we go from here? Human Resource Management Review, 17, 166–179.

Cropanzano, R., Goldman, B., & Folger, R. (2003). Deontic justice: The role of moral principles in workplace fairness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 1019–1024.

DeRidder, R., & Tripathi, R. C. (1992). Norm violation and intergroup relations. New York, NY: Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press.

De Vogli, R., Brunner, E., & Marmot, M. G. (2007). Unfairness and social gradient of metabolic syndrome in the Whitehall II Study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63, 413–419.

DeWall, C. N., Maner, J. K., & Rouby, D. A. (2009). Social exclusion and early-stage interpersonal perception: Selective attention to signs of acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 729–741.

Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P., Hibino, S., Lee, J. K., Tate, U., & Bautista, A. (1997). Leadership in Western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. Leadership Quarterly, 8, 233–274.

Drago, R. (1996). Workplace transformation and the disposable workplace: Employee involvement in Australia. Industrial Relations, 35, 526–543.

Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D., & Pagon, M. (2002). Social undermining in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 45, 331–351.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507.

Eisenberger, R., Lynch, P. D., Aselage, J., & Rohdieck, S. (2004). Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 787–799.

Eisenberger, R., & Stinglhamber, F. (2011). Perceived organizational support: Fostering enthusiastic and productive employees. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Eschleman, K. J., Bowling, N. A., & Alarcon, G. M. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of hardiness. International Journal of Stress Management, 17, 277–307.

Farh, J.-L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support-employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 715–729.

Folger, R., & Pugh, S. D. (2002). The just world and Winston Churchill: An approach/avoidance conflict about psychological distance when harming victims. In M. Ross & D. Miller (Eds.), The justice motive in everyday life (pp. 168–186). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

George, J. M., Reed, T. F., Ballard, K. A., Colin, J., & Fielding, J. (1993). Contact with AIDS patients as a source of work-related distress: Effects of organizational and social support. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 157–171.

Goldman, B. M., Gutek, B. A., Stein, J. H., & Lewis, K. (2006). Employment discrimination in organizations: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management, 32, 786–830.

Gordon, L. V. (1976). Survey of interpersonal values–revised manual. Chicago, IL: Science Research Associates.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Griffin, R. W., & O'Leary-Kelly, A. (2004). The dark side of organizational behavior. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Harlos, K. P., & Pinder, C. C. (2000). Emotion and injustice in the workplace. In S. Fineman (Ed.), Emotion in organizations (pp. 255–276). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Hitlan, R. T., Kelly, K., Schepman, S., Schneider, K. T., & Zarate, M. A. (2006). Language exclusion and the consequences of perceived ostracism in the workplace. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice, 10, 56–70.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hollinger, R. C., & Clark, J. P. (1983). Theft by employees. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Hom, P. W., Tsui, A. S., Wu, J. B., Lee, T. W., Zhang, A. Y., Fu, P. P., & Li, L. (2009). Explaining employment relationships with social exchange and job embeddedness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 277–297.

Horowitz, M. J., & Arthur, R. J. (1988). Narcissistic range in leaders: The intersection of individual dynamics and group processes. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 34, 135–141.

Kane, K., & Montgomery, K. (1998). A framework for understanding dysempowerment in organizations. Human Resource Management, 37, 263–275.

Kanter, R. M. (1987). From the information age to the communication age. Management Review, 76, 23–24.

Kellerman, B. (2004). Bad leadership: What it is, how it happens, why it matters. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Kirkman, B. L., Lowe, K. B., & Gibson, C. B. (2006). A quarter century of culture's consequences: A review of the empirical research incorporating Hofstede's cultural value framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 285–320.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., Trevino, L. K., & Edmondson, A. C. (2009). Silence by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163–193.

Kobasa, S. C. (1979). Stressful life events, personality and health: An inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 1–11.

Lerner, J. S., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2006). Portrait of the angry decision maker: How appraisal tendencies shape anger's influence on. Cognition Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19, 115–137.

Levinson, H. (1965). Reciprocation: The relationship between man and organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 9, 370–390.

MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2005). Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 202–223.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Margolis, J. D., & Molinsky, A. (2008). Navigating the bind of necessary evils: Psychological engagement and the production of interpersonally sensitive behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 847–872.

Martinko, M. J., & Gardner, W. L. (1982). Learned helplessness: An alternative explanation for performance deficits. Academy of Management Review, 7, 195–204.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1159–1168.

Molm, L. D. (1988). The structure and use of power: A comparison of reward and punishment power. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51, 108–122.

Montes, S. D., & Zweig, D. (2009). Do promises matter? An exploration of the role of promises in psychological contract breach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1243–1260.

Morrison, E. W., & Robinson, S. L. (1997). When employees feel betrayed: A model of how psychological contract violation develops. Academy of Management Review, 22, 226–256.

Nahum-Shani, I., & Bamberger, P. A. (2011). Explaining the variable effects of social support on work-based stressor-strain relations: The role of perceived pattern of support exchange. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 114, 49–63.

Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes, and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61, 503–545.

O'Leary-Kelly, A. M., Griffin, R. W., & Glew, D. J. (1996). Organization-motivated aggression: A research framework. Academy of Management Review, 21, 225–253.

Padilla, A., Hogan, R., & Kaiser, R. B. (2007). The toxic triangle: Destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 176–194.

Pinder, C. C., & Harlos, K. P. (2001). Employee silence: Quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. In K. M. Rowland & G. R. Ferris (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 20, pp. 331–369). New York, NY: JAI Press.

Princeton University. (2010). WordNet search. WordNet. Retreived from http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=cruelty&o2=&o0=1&o8=1&o1=1&o7=&o5=&o9=&o6=&o3=&o4=&h=

Raghavan, A. (2002, August 26). Full speed ahead: How Enron bosses created a culture of pushing limits. Wall Street Journal, p. A1.

Raver, J. L., & Nishii, L. H. (2010). Once, twice, or three times as harmful? Ethnic harassment, gender harassment, and generalized workplace harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 236–254.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 574–599.

Robinson, S. L., & Brown, G. (2004). Psychological contract breach and violation in organizations. In R. W. Griffin & A. O'Leary-Kelly (Eds.), The dark side of organizational behavior (pp. 309–337). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Rousseau, D. M. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2, 121–139.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rusbult, C. E., Farrell, D., Rogers, G., & Mainous, A. G. (1988). Impact of exchange variables on exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: An integrative model of responses to declining job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 31, 599–627.

Rusbult, C. E., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2003). Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 351–375.

Schat, A. C. H., Frone, M. R., & Kelloway, E. K. (2006). Prevalence of workplace aggression in the U.S. workforce: Findings from a national study. In E. K. Kelloway, J. Barling, & J. J. Hurrell (Eds.), Handbook of workplace violence (pp. 47–89). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Scott, B. A., Colquitt, J. A., & Paddock, E. L. (2009). An actor-focused model of justice rule adherence and violation: The role of managerial motives and discretion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 756–769.

Shore, L. M., & Shore, T. H. (1995). Perceived organizational support and organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano & K. M. Kacmar (Eds.), Organizational politics, justice, and support: Managing social climate at work (pp. 149–164). New York, NY: Quorum Press.

Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 27–41.

Siegrist, J. (2009). Unfair exchange and health: Social bases of health related diseases. Social Theory and Health, 7, 305–317.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: The role of distributive, procedural and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 434–443.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (2004). Broadening our understanding of organizational retaliatory behavior. In R. W. Griffin & A. O'Leary-Kelly (Eds.), The dark side of organizational behavior (pp. 373–402). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sommer, K. L., Williams, K. D., Ciarocco, N. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2001). When silence speaks louder than words: Exploration into the intrapsychic and interpersonal consequences of social ostracism. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 63, 175–182.

Song, L. J., Tsui, A. S., & Law, K. S. (2009). Unpacking employee responses to organizational exchange mechanisms: The role of social and economic exchange perceptions. Journal of Management, 35, 56–93.

Stinglhamber, F., & Vandenberghe, C. (2004). Favorable job conditions and perceived support: The role of organizations and supervisors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 1470–1493.

Storey, J. (1992). Developments in the management of human resources. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178–190.

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33, 261–289.

Thau, S., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Self-gain or self-regulation impairment? Tests of competing explanations of the supervisor abuse and employee deviance relationship through perceptions of distributive justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 1009–1031.

Tsui, A. S., Pearce, J. L., Porter, L. W., & Tripoli, A. M. (1997). Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: Does investment in employees pay off? Academy of Management Journal, 40, 1089–1121.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1259–1392.

Vredenburgh, D., & Brender, Y. (1998). The hierarchical abuse of power in work organizations. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1337–1347.

Waldman, D. A., Sully de Luque, M., Washburn, N., House, R. J., Adetoun, B., Barrasa, A., … Wilderom, C. P. M. (2006). Cultural and leadership predictors of corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 823–837.

Webster's Online Dictionary. (n.d.). Retrieved August 25, 2011 from http://www.websterdictionary.org/definition/cruelty

Weiner, B. (1972). Theories of motivation: From mechanism to cognition. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Zhao, Z., Wayne, S. J., Glibkowski, B. C., & Bravo, J. (2007). The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60, 647–668.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2000, Fall). The psychology of evil. Eye on Psi Chi, 16–19.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2004). A situationist perspective on the psychology of evil: Understanding how good people are transformed into perpetrators. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The social psychology of good and evil (pp. 21–50). New York, NY: Guilford Press.