8

Can the Organizational Career

Survive? An Evaluation Within

a Social Exchange Perspective

David E. Guest

King's College London

Ricardo Rodrigues

Kingston University London

INTRODUCTION

Research on careers has a long and distinguished history. However, contemporary research on organizational careers can usefully be traced back to the work of a group of scholars based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard in the mid-1970s. During this time, three seminal books were published by Hall (1976), Van Maanen (1977), and Schein (1978) integrating previous work focusing on careers within organizational contexts and setting the cornerstone of the popular view of careers as a “sequence of promotions and other upward moves in a work-related hierarchy during the course of the person's work life” (Hall, 1976, p. 2). These might be played out in a single organization or sometimes across a number of organizations.

According to Arthur (1994), the growing interest in careers within organizations can be explained by two factors. First, between the post-war period and the 1970s, it was assumed that the large corporations that dominated advanced industrial economies were here to stay. The effective management of organizational careers was viewed as a key factor in the success of these corporations. Second, by the 1970s and 1980s, there was a growing interest in Europe and America in the Japanese style of management, particularly in how the organization of work, the culture of cooperation and continuous improvement, and policies of job security and lifetime employment contributed to the success of Japanese firms (Pascale & Athos, 1981).

Managing the traditional career exchange to ensure a good match between individual and organizational goals and needs at different stages in their relationship has been a widely debated topic from the 1970s onward (Ornstein & Isabella, 1993). Elements of this discussion can be found in the literature on internal labor markets (see, for example, Osterman, 1994) that has discussed how internal organizational rules ensured the conditions for vertical career progression and long-term attachment between workers and organizations. Researchers have described how large organizations divided work to create hierarchies and job ladders, often beyond what was technically required, in order to offer workers formal structures of career opportunity and status gradations (Baron & Bielby, 1986). Academics have also explored the formal practices organizations use to plan and develop people's careers, such as communicating job opportunities, providing formal career counseling, clarifying career pathways and criteria for progression, and offering extensive training, performance appraisal, and regular feedback (Baruch & Peiperl, 2000; Gould, 1979); and they have discussed the impact of these practices on organizational identification and performance (Albert, Ashforth, & Dutton, 2000).

The traditional organizational career is perhaps a classic example of a mutually beneficial exchange. In return for good performance and appropriate displays of commitment, the employee receives job security and the possibility of promotion onward and upward in the organizational hierarchy. Despite the apparent benefits to both individuals and organizations, the organizational career of the kind captured in the definition provided by Hall (1976) is frequently described as being under threat. There is a rhetoric about the new career (Arthur, Inkson, & Pringle, 1999), “the boundaryless career” (Arthur, 1994), “career self-management” (King, 2004), and even “the end of the career” (Cappelli, 1999). The central aim of this chapter is to analyze and evaluate this threat. We do so within the context of an analytic framework that draws upon exchange theory and the resource-based view of the firm and by using a range of empirical sources. However as a first step, we need to elaborate on the meaning of the career and outline some of the distinctive features of the exchange implied in the organizational career.

THE CAREER FROM A SOCIAL EXCHANGE PERSPECTIVE

The progressive organizational career enjoyed by managers and some professionals was only ever available to a minority of staff. As Osterman (1994) and others have observed, firms have typically employed a range of internal labor markets. Only those in managerial and sometimes professional internal labor markets are likely to have the opportunity to experience a traditional organizational career. Furthermore, not everyone seeks an upwardly mobile career. Therefore, we need a broader, more encompassing definition of a career if we are to capture the range of career experiences. Arnold (1997), for example, describes a career as “a sequence of employment-related positions, roles, activities and experiences encountered by a person” (p. 16). This broader definition can apply to all workers and is worth keeping in mind while we focus more narrowly on the careers of the managerial and professional staff.

We have suggested that the traditional organizational career represents a classic form of exchange. Closer inspection suggests that this is a highly complex and in some respects unusual exchange. If we consider the exchange in terms of the psychological contract (Rousseau, 1995; Taylor & Tekleab, 2004), it is highly relational and long term. It relies heavily on what might be termed a “career promise,” whereby a heavy investment over a period of time by the employee is offered in the expectation of a return at some future date in the form of promotion. It therefore entails a strong element of postponed gratification. The challenge for the organization is to devise ways to retain the probability in the mind of staff that the promise will be kept. Yet, inevitably, in a typical pyramid-shaped organization structure, not everyone will be able to rise up the hierarchy. In this context, we can use aspects of exchange theory to explore how this challenge can be addressed. The key components are trust, fairness, perceived organizational support, and delivery of sufficient promises within the psychological contract. We will examine each in turn.

Trust is a central feature of any successful exchange model. At the point of recruitment, those embarking on what they hope will be progressive organizational careers—notably graduates entering junior management posts—may believe that a “career promise” has been made to them, even if the language in which it was couched was somewhat ambiguous, leaving the “promise,” at best, implicit. In responding to this promise, they are trusting the organization and its agents to deliver on the promise. Coyle-Shapiro and Conway (2004) note “one party needs to trust the other to discharge future obligations (i.e. to reciprocate) in the initial stages of the exchange and it is the regular discharge of obligations that promotes trust in the relationship” (p. 7). However, in the case of the career promise, there is considerable uncertainty about when the delivery will occur, and in practice, both parties are making an investment in the hope of a future return. The new entrants therefore need to demonstrate their potential, and the organization needs to provide evidence to reinforce the trust about future delivery of promotion. The organization may achieve this by pointing to the experience of previous cohorts of graduates, by providing development opportunities, by direct feedback on progress, and by renewal of promises. However, trust in delivery of advancement is likely to diminish over time, particularly if other managers seem to be making swifter progress within what has been described as the career tournament (Rosenbaum, 1979). It has also been suggested (Smola & Sutton, 2002) that contemporary graduates are less patient and less prepared to wait. Furthermore organizations are eager to identify key talent at an ever earlier stage to ensure that they are developed and retained. The scope for a number of young managers within a particular intake to fall by the wayside, reflecting a breakdown in trust, is therefore high. Indeed, in their meta-analysis of the consequences of psychological contract breach, Zhao, Wayne, Gliboswski, and Bravo (2007) found evidence to support the role of trust as a mediator between breach and outcomes such as reduced commitment and increased intention to quit.

One way in which trust might be maintained is by demonstrating high levels of organizational support. Shore and Shore (1995) highlight the career challenge by suggesting that employees are inherently disadvantaged in their exchange with the organization because they have less power, because they have to deal with a variety of agents of the organization, who may communicate different messages, and because of the typical delay in the delivery of promises and obligations. To overcome this disadvantage, Eisenberger, Jones, Aselage, and Sucharski (2004) have argued that the organization needs to demonstrate its support for employees.

In many cases, promises may lack specificity, leading to uncertainty about whether the organization has fulfilled its obligations. For instance, organizations may promise prospective employees substantial future pay raises or frequent promotions. In subsequently evaluating whether the organization has fulfilled such qualitative promises, employees with high POS may be inclined to give the organization the benefit of the doubt in determining whether the contract has been fulfilled. (p. 215)

There is evidence (Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002) that support will be perceived as more valuable when it is voluntary rather than required and when it is distinctive to the individual rather than general. Support can come in the form of words but, at some point, will need to be translated into action.

The gains made by some indication of personalized support may reinforce the commitment of one manager but, unless carefully handled, can do so at the expense of others, raising the question of fairness of treatment. Shore and Shore (1995) suggested that although both substantive and procedural fairness are essential to a positive exchange, procedural fairness will be more important for maintaining a sense of perceived organizational support, partly because substantive rewards in the context of careers are much rarer. However, there is potential ambiguity concerning fairness because although both parties can recognize the importance of procedural fairness, organizations will wish to be selective in identifying talent and individuals will be pleased to be selected out of the pack. Therefore, in the context of a scarcity of the key distributive reward of promotion, there is considerable potential for perceptions of unfairness and an increased need for transparent procedural fairness.

The final relevant component of the exchange model is the psychological contract. The psychological contract addresses the reciprocal promises and obligations between the individual and the organization (Rousseau, 1995). A conceptual distinction is often made between transactional and relational psychological contracts (Rousseau, 1989). Although the operational distinction between these two types of psychological contract has proved difficult to sustain, particularly when defining the boundary between them (Roehling, 2004), the distinction has conceptual and analytic value in the present context. Transactional contracts are explicit, often relatively short term, and easy to monitor, whereas relational contracts are less clear-cut or specified, more long term, and much less straightforward to monitor. As a result, there is more scope for misinterpretation and consequently for breach of the deal.

The promise of a career is an extreme example of a relational psychological contract. It implies long-term exchange in which the outcomes are uncertain and cannot be specified at the outset. The contributions from the employee are usually unclearly specified and may become tied to a set of normative obligations about issues such as working hours and travel that are embedded in the organizational culture. In general, therefore, the content, specificity, and timing of the delivery of organizational careers are highly uncertain. This uncertainty applies to both parties. The employee can be uncertain about how much time she has to demonstrate her potential, about the criteria for high potential performance, and about who makes the key judgment about that performance. As noted earlier, the organization faces uncertainty in its attempts to identify the high potential managers and to do so in a timely fashion that enables it to develop and reward those it particularly wishes to retain. Although rewards can take the form of pay rises, development opportunities, and positive feedback, the key reward is promotion. Promotion is distinctive because it typically brings with it a bundle of additional rewards such as increased pay, higher status, more power, more autonomy, and more responsibility. The essentially ambiguous and uncertain nature of the predominantly relational content of the career dimension in the psychological contract leaves plenty of scope to believe that promises have not been kept.

Lambert, Edwards, and Cable (2003) and Montes and Irving (2008) have demonstrated that breach of relational features of the psychological contract is much more serious than breach of the transactional components. Breach of perceived career promises can be particularly serious because of the bundle of outcomes associated with career advancement and may precipitate an intention to leave the organization. If organizational changes are eroding opportunities for career advancement, then the viability of the traditional organizational career, involving a long-term commitment to the organization in exchange for career progress, is likely to be under increasing threat.

In summary, the traditional organizational career represents a distinctive, highly complex and highly uncertain form of exchange. For both individuals and organizations, there are considerable mutual gains from successful organizational careers, which helps to explain why they have persisted. There are also considerable risks engendered by the complexity of the exchange that can result in at least one party perceiving that the exchange has failed. Despite the potential benefits of the traditional career model for both employees and organizations, it is has come under increasing critical scrutiny in recent years, with some observers even claiming that it is unlikely to survive.

The challenge to the organizational career can be understood and analyzed at two levels. First, there is a general argument about the changing context within which organizations operate and that may be making it less feasible to offer traditional organizational careers. Second, there is a more specific argument about the human resource strategies and especially the career and development strategies that firms need to apply in order to thrive that provides a more selective approach to the conditions under which organizational careers are desirable. These potentially contrasting perspectives then provide a context within which to explore relevant empirical evidence. We start by analyzing the wider context.

THE CHANGING CONTEXT OF CAREERS AND CAREER MANAGEMENT

Commentators have identified a range of global trends affecting the way in which organizations are forced to operate if they wish to survive. These include the growth of the knowledge-based and global economy, the impact of technology, migration, the growth of the professions, and changes in work values in advanced industrial societies. We briefly review these broad trends before focusing more specifically on how they might affect the ability of organizations to offer traditional careers.

The Knowledge-Based Economy and Globalization

Industrial restructuring in the United States and Europe in recent decades is associated with globalization and the shift toward a knowledge-based economy (Mirvis & Hall, 1994). The economy of hardware is being replaced by the economy of software, where economic wealth is grounded on “the creation, production, distribution and consumption of knowledge and knowledge-based products” (Harris, 2001, p. 22). The shift toward a knowledge-based economy, compounded by the increasing pace of globalization, has undoubtedly shaped the competitive environment, fueled uncertainty among workers and organizations, and placed additional pressures on the traditional career model. Globalization and its opening up of a more international labor market seem to be intensifying the war for talent in developed countries and forcing companies to fight to attract and retain the most skilled workers (Chambers, Foulon, Handfield-Jones, Hankin, & Michaels, 1998). The growth of an international labor market for staffin fields such as finance can distort internal labor markets as organizations vie with each other to attract and retain those they regard as key to their future success. One possible consequence of engaging in the war for talent, as Pfeffer (2001) observes, is that companies may be downplaying their own talent to the detriment of newcomers and therefore encouraging workers to seek career progression through interorganizational mobility rather than through internal promotion.

Commentators have also warned that the premium placed on knowledge, associated with higher educational levels of the workforce in developed countries and uncertainty fostered by large firm decentralization, frequent restructuring, and delayering (Littler, Wiesner, & Dunford, 2003), may boost a “hired gun” career mindset among those who possess valuable and rare human capital (Barley & Kunda, 2004). For these people, selling their skills in the market to the highest bidder on a short-term basis may be more appealing than long-term commitment to an organization. All these factors have affected the nature of work, the traditional employment relationship, and thus it is argued, the viability of careers within organizations.

Technology

The widespread use of information and communication technologies may also be contributing to changes in the nature of employment and the traditional career exchange. Technological change destroys old jobs and creates new ones, usually having a positive effect on employment in the long run (Freeman, Soete, & Efendioglu, 1995). However, the newly created jobs may be of a different nature and involve different sets of promises and expectations when compared with traditional organizational career jobs. Flexible employment arrangements seem to have become more common in some industries and geographical locations where new technologies are more prevalent. Perhaps the epitome of new employment relations can be found in locations like Silicon Valley (Saxenian, 1996), where information technology (IT) professionals frequently move between competing firms in a process that allows them to acquire marketable skills and gives organizations access to talent that drives innovation. The employment patterns of Silicon Valley have been considered by many as “a trendsetter, both for the United States and for the world” (Carnoy, Castells, & Benner, 1997, p. 28). If this is the case, the short-term transactional employment relations that are the norm in these industries may be a sign of things to come.

Migration

In tandem with economic globalization, immigration flows from developing countries have created pressures on traditional career arrangements. In particular, immigration has generated apprehension that a vast reservoir of inexpensive labor would be made available to employers in developed countries, threatening natives’ job stability and bidding down salaries (Borjas, 2006). Even though there is evidence that immigration significantly affects the supply of skills in locations with a high concentration of migrants and, consequently, occupation-specific wages and employment rates (Card, 2001), its impact on employment and career patterns is complex and to a large extent dependent on national policy and the profile of migrants. Aydemir and Borjas (2007) have recently compared the impact of immigration on wage rates in different countries between 1980 and 2000. For instance, immigration to the United States is disproportionally low skilled and therefore tends to create pressures at the low end of the income distribution. In contrast, in Canada, where migrants are mainly high-skilled workers, immigration seems to be affecting mostly those at the high end of the labor market. An influx of high-quality but potentially cheaper managers and professionals into organizational hierarchies can distort internal labor markets.

Professionalization

Professional occupations have codified areas of knowledge, specified training, and in some cases, control over access to work (Tolbert, 1996). The value system of traditional professions, such as medicine and law, is now resonating among other groups of workers such as engineers, nurses, pharmacists, accountants, psychologists, and teachers (Evets, 2003). The growth of professional bodies places the organizational career model under pressure in a number of ways. Because most professionals are currently employees in professional or bureaucratic organizations, instead of self-employed, they must manage loyalties toward their employer and their profession (Wallace, 1995). There is an ongoing debate about whether organizational and occupational value systems are compatible. For instance, in a study with accountants, Sorensen and Sorensen (1974) found that perceived conflict between professional and organizational loyalties resulted in job dissatisfaction and turnover. Because a profession is based on a distinctive body of knowledge, it can be easily transferable across organizations so that an occupational career becomes an alternative to the traditional organizational career. It seems that for a growing proportion of the workforce, the occupation or profession is an increasingly salient locus of careers that will help to shape people's expectations of the employer–employee relationship.

Changing Work Values

There is an extensive literature analyzing generational differences in work values and suggesting that the meaning of work is changing for younger generations, who give a higher priority to achieving a healthy work–life balance rather than a traditional organizational career. Although some of these studies are cross-sectional and therefore need to be treated with caution, Smola and Sutton (2002) replicated a study on work values previously conducted in the United States in 1974. Their evidence suggests that in comparison with Generation X (born between the early 1960s and the mid-1970s), the Millennials (born between 1979 and 1994), who are now entering the labor market, are less loyal to their organizations and more committed to their own personal goals. They also consider work to be a less important part of their lives and are more willing to stop working if they win a large amount of money. All this suggests that those who in the past would have become the stereotypical “company men” seem to be more reluctant to accept the traditional exchange of long working hours and loyalty and commitment to their organizations in return for job security and hierarchical promotion. This attitudinal change may be fostered by changing underlying work values, as the literature suggests, or by workers reacting to fewer career opportunities.

Consequences of Changes for Internal Labor Markets

It is suggested that internal labor markets are more permeable to the external environment in a number of ways (O'Mahoney & Bechky, 2006). First, it has been argued that wages seem to be more sensitive to the value of skills in the market and individual performance than to internal organizational principles (Osterman & Burton, 2005). Second, it has been suggested that companies are more reluctant to invest in training and seem to be emphasizing workers’ responsibility for the development of their own human capital (Peiperl & Baruch, 1997). Third, some commentators have linked the growth of the temporary work industry in the United States and Europe from the 1970s onward (Kalleberg, 2000) to the idea that a stable and committed workforce is no longer a priority for companies, who are turning to the external market in search for skills and just-in-time workers (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1994). These trends seem to be associated both with an individualization of employment relations (Rousseau, 2005) and a decline in trade union membership and collective bargaining (Brown, Deakin, Nash, & Oxenbridge, 2000). In summary, the argument is that multiple pressures are making it less feasible for organizations to offer the traditional organizational career. At the same time, it is also argued that changes in values among those entering the labor market mean that they are less enthusiastic about pursuing the traditional organizational career. Therefore, the traditional organization career seems to be under pressure from both partners to the exchange.

THE CASE FOR RETAINING THE ORGANIZATIONAL CAREER

Despite the argument that a range of pressures are making it more difficult to provide careers and keep “career promises,” many organizations continue to recruit graduate cohorts and some other staff with the promise of a career. Why do they do this? Part of the answer can be found within an analysis using the resource-based view of the firm (Barney, 1991). This highlights the importance for the competitive advantage of organizations of acquiring and retaining human resources that are rare, valuable, inimitable, and nonsubstitutable. Barney and Wright (1998) have shown how these relate to human resource practices, emphasizing the importance of investing in critical human capital. Lepak and Snell (1999) have developed a framework within which organizations can classify the various types of human resource, identifying those staff who are considered to be central to the firm's success and for whom the firm might wish to provide an organizational career.

The Lepak and Snell model has two dimensions concerned with whether staff are high or low with respect to the uniqueness and the value of their human capital. They suggest that those high on both dimensions are the staff that firms should seek to attract and retain by providing an organizational career. For others, such as, for example, certain kinds of lawyers and consultants who are required only occasionally, they would advocate some form of alliance relationship. In the case of other staff, whose contribution is less valuable and who are easily replaceable, Lepak and Snell suggest there is no case for a long-term investment. The implication is that even among the managerial and professional group within an organization, only a minority have the kind of distinctive and valuable human capital that justifies the full investment in their career. Lepak and Snell (2002) and Peel and Boxall (2005) have demonstrated some validity for the types and patterns of investment implied by the framework, and Lepak, Takeuchi, and Snell (2003) reported higher performance among firms that adopt human resource strategies that align with the framework.

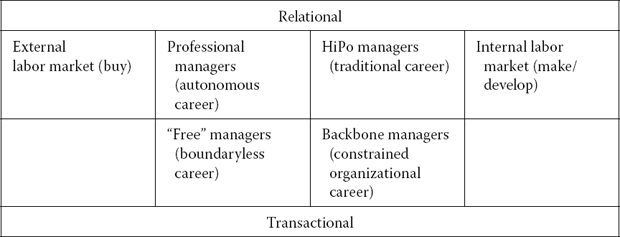

The resource-based view of the firm justifies the case for investing in human resources, and the Lepak and Snell model helps to explain why organizations might wish to adopt a selective approach to career management. However, it is directed toward the whole workforce and is not sufficiently focused on career issues for our present purposes. To develop an analytic framework to explore contemporary organizational careers, we can draw on three perspectives. The first is transaction cost economics (Williamson, 1975), which heavily influenced the resource-based view of the firm and which highlights a core choice, mirrored in the Lepak and Snell model, about whether to “make” or “buy” staff. The second perspective, reflected in exchange theory, concerns the kind of relationship that the organization seeks with its staff. This can most usefully be analyzed in terms of the psychological contract and the distinction, noted earlier, between relational and transactional contracts. Finally, Schein (1978) has shown how workers have different career preferences, reflected in what he terms career anchors, that can lead them to pursue different kinds of career paths. He distinguishes between the general progressive hierarchical career, where progress is reflected in promotion, which can occur across various parts of an organization; the professional or technical/functional career, where progress will occur within a narrow professional hierarchy or take the form of greater depth rather than promotion, reflected in increased expertise and autonomy; and what he describes as movement toward the center of the organization. This can occur among managers who are not considered as high potential but through their tacit knowledge become an essential cog in the smooth operation of the organization. They form a kind of backbone of middle management. These dimensions provide an opportunity to distinguish the types of managerial personnel and the associated careers, illustrated in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1 shows four types of career. In the first quadrant, at the top right-hand corner, is the traditional organizational career, geared toward high potential (HiPo) managers who will be developed by and promoted within the organization. They are identified as potential organizational leaders, key to the success of the organization, and with whom the organization will have a broad, highly relational exchange.

In the second quadrant, at the bottom right-hand corner are what we have termed the backbone managers. These may have started out as part of the high potential cadre but have fallen back in the career tournament. They are a moderately valuable resource because they have accumulated a lot of specific inside knowledge of the sort associated with Schein's third type of career. They are the middle managers who keep the wheels oiled. They may stay in an organization because their specific skills make it difficult to move to other organizations, and they may rise to the middle ranks of the hierarchy, but from an organizational perspective, they are dispensable because they are neither rare nor particularly valuable. They fit in the right-hand side because the organization will have been largely responsible for their development and because they possess specific rather than general knowledge and skills. The psychological contract will be more limited and more transactional than that of the HiPo managers in so far as organizations invest less in the exchange. In practice, it may come closer to what Rousseau (1995, p. 98) has termed a “balanced” rather than a purely transactional exchange.

FIGURE 8.1

A model of managerial career types. HiPo, high potential.

The third quadrant, in the top left-hand corner, includes professional managers, those who have developed a strong professional knowledge base, typically linked to recognizable qualifications. Within the management group, they would typically include finance and accountancy experts. Some will move into the top right-hand quadrant, but many will retain their specialism. This category also includes the professional workers in public sector and not-for-profit organizations such as hospitals. Their knowledge and skills are developed outside the organization, but their expertise can become invaluable to the organization and some can be very hard to replace. The professional expertise gives them considerable autonomy, and their careers will often take the form of gaining greater depth in their distinctive expertise. Therefore, they will have a highly relational contract reflected in the autonomy and the high level of trust inherent in that autonomy. Growth of professional autonomy rather than hierarchical promotion often represents the development of their career.

The final category, in the bottom left-hand corner, represents what has come to be known as the “new” career. This has been described in terms of the “free worker” (Knell, 2000), free in the sense that the worker is not tied to any organization. Their loyalty is to themselves and their career rather than to any organization. When they work in organizations, the relationship is transactional and conditional. In this context, one can think of certain kinds of bankers and technology experts. Organizations may wish to retain them, but they will remain with an organization only so long as it suits them.

The broad argument within “the new career” model is that there is pressure to move away from the other types of career toward a boundaryless career. The implication in much of the writing is that this is driven by individual preferences as much as, if not more than, by organizations, more particularly because these free workers may be highly talented knowledge workers of the sort organizations would wish to retain. Given their centrality to the contrast between the “old” organizational career and the “new” career, we need to explore this category in more detail.

THE NEW CAREER

The new career involves a shift from a relationship based on the exchange of loyalty and commitment for long-term employment security and career progression to a relationship based on the exchange of performance for the opportunity to develop marketable skills and benefit from competitive wages over a short period of time (Arthur, 1994; Sullivan, 1999). The old career deal was based on mutual interests built around the traditional long-term career exchange. The new deal is typically a more short-term exchange between organization and individual requiring the organization to provide meaningful work experiences and scope for development in exchange for a commitment to work toward organizational goals (Briscoe & Hall, 2006). Hence, under the new deal, success is no longer measured by one's position in a structured organizational hierarchy, power, and income, but rather by one's own self-defined notion of achievement that may encompass, for instance, achieving a satisfactory work–life balance, doing work that contributes to society, or applying one's ideas to creating a new business (Hall & Mirvis, 1995). In this context, three concepts that have been widely associated with this new perspective are the boundaryless career, the protean career, and career self-management. We briefly explore and then evaluate each in turn.

The idea of the boundaryless career, coined after the metaphor of the boundaryless organization, is frequently associated in the literature with mobility across jobs, functions, and organizations, as well as the demise of rigid job structures and hierarchical career paths (Arthur, 1994; Briscoe & Hall, 2006). The concept is, however, broader and richer. Arthur (1994) has highlighted several distinctive aspects of physical and psychological boundarylessness, including how such careers draw validation from outside the present employer, are sustained by extraorganizational networks or information, and reflect a perception of a career without structural constraints and that is, therefore, boundaryless.

The concept of the protean career focuses mainly on the “internal” career, highlighting changes in people's career values and attitudes. A protean career is “one in which the person, not the organization, is in charge, the core values are freedom and growth, and the main success criteria are subjective (psychological success) vs. objective (position, salary)” (Hall, 2004, p. 4). The protean career is driven by a predisposition to act according to one's values and beliefs (Briscoe & Hall, 2006), involves a renegotiation of the psychological contract (Hall & Mirvis, 1995) based on the individual's values, and involves commitment to personally meaningful work experiences as the main route to achieving psychological success.

The boundaryless career and the protean career both reflect the idea that organizational boundaries have become more permeable (Arnold & Cohen, 2008) and, as a result, that membership of an organization or department is more transient and ambiguous (Miner & Robinson, 1994). The suggested demise of organizational careers does not imply the end of job opportunities or career advancement, but rather that these are to be found in career paths that involve frequent moves between different organizations (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1994). To navigate the new career landscape successfully, people are being advised to consider careers as their own property and to take responsibility for managing their own careers (King, 2004) through developing what have been described as intelligent career competencies (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1994). People are encouraged to decouple their identities from their jobs and work settings and advised to build their identity around their occupation, personal interests, or other nonwork activities. By the same token, it is suggested that developing marketable skills and abilities, rather than firm-specific skills, and participating in networks that allow access to work opportunities beyond the boundaries of one's current employer might contribute to career success in the boundaryless career era (DeFillippi & Arthur, 1994).

Although the idea of “the new career” is well established within the career lexicon, both the protean and the boundaryless career concepts have attracted criticism on conceptual, empirical, and operational grounds (Arnold & Cohen, 2008; Inkson, 2006; Pringle & Mallon, 2003). In this section, we briefly outline three conceptual issues raised by the current view on the new career. The next section discusses in greater detail the extent to which the evidence supports the demise of organizational careers.

The first issue that needs further discussion is the assumption that the context in which companies operate is causing the demise of organizational careers. The basis for the new career “acknowledges the unpredictable, market-sensitive world in which so many careers now unfold” (Arthur, 1994, p. 297), echoing some of the core arguments of literature on globalization and technological change previously outlined in this chapter. But are these trends really forcing organizations to lose their role as the main locus of people's careers? A number of economists have argued for some time that the impact of contextual and organizational changes on wages, employment stability, and careers has been exaggerated (Krugman, 1994). The rhetoric of change has not been systematically linked to the reality of contemporary organizational career practice, and there is therefore a need to explore in more detail the link between the changes in the competitive environment and any evidence supporting the rise of the new career.

The second issue concerns the conceptualization and operationalization of the new career with its focus on the permeability of, and movement across, organizational boundaries. The primacy ascribed to organizational boundaries is reflected both in the conceptualization (Sullivan & Arthur, 2006) and in the operationalization of the boundaryless and the protean career (Briscoe, Hall, & DeMuth, 2006). If organizational boundaries have become permeable, does that mean that careers are unfolding in an unstructured environment? Or are careers embedded in other domains, which may then be becoming more salient and impermeable? These questions are difficult to answer within the current framework of the new career. A more complete elaboration and operationalization of the concept needs to consider the nature of boundaries and to discuss how potentially salient boundaries such as the organization, the occupation, the type of employment contract, the divide between work and nonwork, and geographical boundaries shape people's career choices and trajectories (Rodrigues & Guest, 2010).

The final issue that has been largely overlooked in the literature is the breadth of the new career, both in terms of where and to whom the concept applies. Thus far, the discussion on the empirical basis of the new career has been mostly located in the United States (see, for instance, Cappelli, 1999; Jacoby, 1999). Even though several aspects of career boundarylessness have been researched in a number of countries, such as New Zealand (Pringle & Mallon, 2003), France (Cadin, Bailly-Bender, & Saint-Giniez, 2000), and Germany (Stahl, Miller, & Tung, 2002), the literature has not consistently debated whether this is predominantly an American phenomenon or more widespread. By the same token, the literature has not fully discussed whether the new career can be generalized to all workers or whether it applies only to particular segments of the working population. For instance, Arthur (1994) uses the stereotypical Silicon Valley career and the careers of academics, carpenters, and real estate agents as examples of career boundarylessness, whereas Cappelli suggests that the new career is limited to “white-collar and managerial jobs, the ones that truly were protected under the old model” (Cappelli, 1999, p. 148). Given these questions about the new career concept, there is a need for a fuller empirical exploration of how far it has become established or whether the traditional organizational career appears to have survived.

HAVE ORGANIZATIONAL CAREERS SURVIVED?

In this section, we will explore the validity of the new career in two ways. First, because the new career model is permeated by the idea that employment no longer means holding a permanent job within an organization, but is instead defined as “a temporary state, or the current manifestation of long term employability” (Arthur & Rousseau, 1996, p. 374), one should expect an overall growth of temporary employment. Second, if people are moving across rather than within organizations, we would expect to see a growth in interorganizational movement and an associated reduction in organizational tenure. To explore these two issues, we used Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data for a number of countries, such as the United States and Japan, and major European economies such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and France.

The OECD Employment Outlook of 2002 shows that the cumulative employment growth in the whole OECD area during the 1990s was 11.6%, of which 4.2% was accounted for by temporary employment (OECD, 2002). There are, however, significant differences between countries. In the United Kingdom, Japan, and more particularly the United States, the growth of total employment was mainly attributable to permanent employment. In contrast, in Germany and France, temporary employment accounted for most job growth. In general, the evidence indicates that permanent employment is still the dominant pattern of employment creation in the OECD area. Differences between countries are more readily explained by the strictness of employment protection on permanent contracts in Germany and France, when compared to the United States and the United Kingdom (OECD, 2006), than by the changing nature of employment and careers.

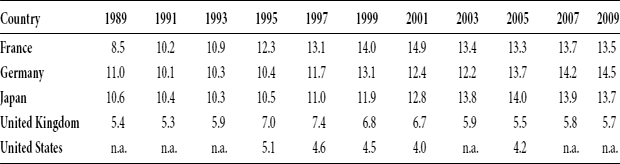

A similar pattern is found when analyzing recent trends in the use of temporary employment. The share of temporary work within overall employment has increased in France, Germany and, more moderately, Japan between 1989 and 2009 (Table 8.1). In contrast, the percentage of temporary employment in the United Kingdom increased in the 1990s but declined between 2001 and 2009, whereas in the United States, temporary employment declined slightly from the mid-1990s onward.

The evidence on temporary work does not support the view that employment is becoming increasingly short term and transactional in nature. Organizations may be outsourcing some of their noncore activities, but there is no clear trend indicating that organizations are seeking a more outsourced or temporary workforce. Although there is evidence to suggest that up to two thirds of temporary workers would ideally prefer permanent contracts (Guest, Isaksson, & De Witte, 2010), there are good reasons why certain categories of workers may prefer temporary employment. For instance, women and older workers, who often prefer flexible work arrangements, have increased their participation in the labor force (Kalleberg, 2000). The service sector, where jobs are more seasonal and temporary, has grown significantly in developed economies (Smith, 1997). Temporary work can also provide an opportunity for young workers to explore distinct occupational identities (Ibarra, 1999) at an early career stage. Research suggests that temporary work is an important route into permanent employment with, on average, between one third and two thirds of temporary workers moving into a permanent position within 2 years (OECD, 2002). In fact, temporary employment seems to have become a common recruitment strategy for organizations (Jacoby, 1999). In summary, several factors, other than organizations’ declining interest in maintaining a committed workforce or individuals’ motivation to pursue independent careers, can account for any small growth of temporary work.

TABLE 8.1

Percent Share of Temporary Employment 1987–2009 (Dependent Employment)

n.a., not available.

Source: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Employment Statistics Database, http://www.oecd.org/statisticsdata/0,3381,en_2649_37457_1_119656_1_1_37457,00.html, 2011. Own tabulation.

In previous work (Rodrigues & Guest, 2010), we reviewed the evidence on job tenure in a number of countries between the 1980s, the period about which the new career was being proposed as the dominant form of employment, and the mid-2000s. This revealed that in the United States, the evidence overall suggests that from the 1980s onward job instability affected particularly men, blacks, younger workers, and less skilled workers. In contrast, well-educated U.S. staff of the sort found in management do not display any marked reduction in organizational tenure of the sort we would expect if the boundaryless career had taken hold. In Europe, the evidence clearly suggests that both workers and organizations still value and retain traditional careers. In the large European economies of the United Kingdom, France, and Germany, overall job tenure has been increasing since the early 1990s. This trend seems to be led by a slight increase in job tenure among women, whereas job tenure among men seems to be essentially stable over the entire period. Updated evidence to 2009 suggests that the recent economic recession has not had a deleterious impact on traditional employment and career patterns. This shows that even at a time when organizations could afford to attract workers from a wider pool of talent, due to the recent waves of bankruptcies and increasing unemployment rates (OECD, 2010), both employers and employees seem to value the benefits of a long-term traditional exchange.

Overall then, and returning to our model of managerial career types, the evidence suggests that the different forms of career exchange proposed should be viewed as developing alongside rather than competing with each other for a dominant career model. Our analysis shows that organizational tenure has not changed significantly since the 1990s and temporary employment has not grown greatly, suggesting that traditional organizational careers are surviving and that the rhetoric of change seems to have underestimated the strength of the mutual commitment between individuals and organizations. Although the free worker ethos may be pervasive in specific contexts, such as Silicon Valley, it is highly unlikely that this model will ever apply to the majority of workers. Traditional organizational careers are likely to persist in the future and be offered to a minority of managerial and professional workers possessing valuable and rare human capital. By the same token, most workers will continue to have access to limited possibilities of promotion. Where we are likely to see some growth, fostered by the increasing professionalization of the workforce, is in the autonomous career type. Our model is therefore useful to address diversity in career exchange and may constitute a basis to discuss trends in the career deal of different types of worker.

SEPARATING THE RHETORIC FROM THE REALITY: THE FUTURE OF ORGANIZATIONAL CAREERS THROUGH THE LENS OF EXCHANGE THEORY

Our analysis has shown that the traditional career exchange is particularly complex and potentially highly fragile. It has been argued by a number of observers that a range of global trends are presenting a serious challenge to the organizational career and to the desire of organizations to perpetuate it. This has encouraged these same observers to anticipate the end of the organizational career and its replacement by a more protean, bound-aryless career and a career that is managed by individuals rather than by organizations. When this pronouncement of changes to the nature of careers is coupled with sometimes loose discussion about “old” and “new” careers, the rhetoric of the new career can be appealing. The empirical evidence challenges this rhetoric. The new career and claims for the end of the organizational career are usually allied to assumptions about increased mobility and a growth in temporary work. The empirical evidence about job tenure and temporary employment shows high levels of stability over quite long periods of time including the period when the advent of the new career was proclaimed. This evidence confirms that there has been no significant trend on the part of organizations to reduce tenure or to shift from permanent to temporary workers.

A further challenge to the rhetoric comes from the logic of the resource-based view of the firm, which, as Barney and Wright (1998) suggest, points to a need for organizations to attract and retain those key staff who are likely to provide competitive advantage. This results in a strong case for retaining the traditional organizational career. This case is reinforced by the desire of organizations to win the “war for talent” on the assumption, despite a continuing increase in the supply of well-qualified graduates, that such talent is scarce.

The other side of the coin concerns the workforce. The rhetoric suggests that values have changed, resulting in an increasing reluctance to engage in traditional organizational careers. The numbers applying to enter graduate careers in large organizations challenge this assumption because they remain as robust as ever. Yet the workforce is changing. There are more women in the labor force, and there are more professional and knowledge workers with potentially transferable skills. There is also quite good evidence of some generational change in values. However, these values may not be deeply embedded. Sturges and Guest (2004) present evidence suggesting that many of those who enter organizations giving a high priority to work–life balance get drawn into an organizational career and sacrifice other aspects of their life. At the same time, they maintained at least an illusion of control over the career. Therefore, a common response was to accept that work–life balance was currently out of kilter but that once the current project or job was completed, they would restore the balance.

From a different perspective, the work of Hochschild (1997) is insightful in revealing how some organizations are succeeding in creating attractive work environments where individuals feel they have autonomy. Indeed, sometimes a regimented home life, with a sequence of family and other commitments, can make the work organization appear a relatively peaceful haven. Research is beginning to reveal how job embeddedness, reflected in fit with both the organization and the environment outside work, can help to increase retention (Lee, Mitchell, Sablynski, Burton, & Holtom, 2004). Evidence is also accumulating about the benefits for organizations and their staff of pursuing a high-commitment human resource strategy (Combs, Liu, Hall, & Ketchen, 2006). In other words, the exchange process to retain the commitment of contemporary employees extends beyond the traditional domain of the career.

Our analysis suggests that there are likely to be increasingly diverse organizational patterns of career management both between and within organizations. Banks provide an example of this and also of the inherent problems in such an approach. They offer traditional careers for a significant proportion of their staff; but most large banks have quite separate human resource policies and practices for the key financial experts who deal in the more esoteric but potentially highly profitable aspects of banking. For this second group, the exchange is highly transactional, based on high salaries and more particularly high performance-related financial rewards. However, as we have seen, these potential bonuses encourage risk taking and a focus on personal transactional outcomes that may not be in the long-term interests of banks. These bankers are examples of free boundaryless workers within the new self-managed career; however, with the freedom comes responsibility, and they are also the new mercenaries of organizational life that banks and even governments are struggling to control.

The foregoing analysis presents a strong case for retaining a relational career contract for a significant proportion of managers. However the career-related exchange has become more complex, and the risk that it will not always be possible for organizations to deliver their side of the exchange may have increased. The alternatives seem to be either to restrict the promises or to risk breaching the psychological contract with its probable negative consequences (Montes & Irving, 2008). The former may result in failing to attract key talent; the latter may risk losing them once they have joined. The evidence from experience in the United Kingdom is that as much as half the graduate intake leaves organizations within 3 years, mainly because they feel that they have not received the kind of development that they had been led to expect (Sturges & Guest, 2001). However, if organizations provide a degree of autonomy to encourage job crafting (Wrzensniewski & Dutton, 2001), then individuals may create their own development opportunities. As Nicholson and West (1988) have shown, many jobs into which people move are newly created jobs, and the scope to “craft” their jobs to fit both organizational and personal aspirations is considerable.

The evidence suggests that it is a combination of fulfilling career promises within the psychological contract, maintaining a sense of fairness in procedures, and maintaining trust in the organization that will be crucial to retain key staff. The antecedents to this will include a strong sense of perceived organizational support, which can be reinforced through personalized exchanges. Reinforcing this exchange perspective, it is essential to have in place a set of high-commitment human resource policies and practices (Pfeffer, 1998) and to ensure that they are effectively implemented (Khilji & Wang, 2006). Bowen and Ostroff (2004) have presented a convincing case for a strong human resources system reflected in a climate that supports consistent implementation of human resources and, in so doing, builds a sense of trust, fairness, and support.

What all this suggests, in practical terms, is that organizations should continue to seek to retain the commitment of their staff and that the career promise, in suitably modified and cautious form, is one way of pursuing this. Yet the career exchange is becoming more complex and more challenging to manage. External pressures and market turbulence mean that organization structures and hierarchies are in a state of semipermanent flux, rendering career promises highly risky. Organizations have to seek commitment yet promise flexibility to accommodate a more diverse and increasingly feminized workforce. They have to promise opportunities for career self-management while seeking to manage careers in the organization's best interests. In addition, most organizations have to develop their in-house talent while operating in the external labor market to buy in key human resources to enhance their competitive advantage. One consequence may be the growth of what Rousseau (2005) has labeled as idiosyncratic deals. All this presents a distinct challenge to career management and in particular to the management of fairness. A further implication for managers is that they should be cautious in accepting the rhetoric of “the new”—in this case, “the new career”—without first scrutinizing the evidence on which it is based.

In conclusion, we have analyzed the status of the traditional career within the context of exchange theory. This has confirmed that exchange theory has considerable utility as an analytic framework. In particular, we have drawn upon various components of exchange theory including the psychological contract, fairness, trust, and social support. This rich array of elements helps to deepen the analysis and also to highlight a range of policy issues and choices. Our analysis demonstrates that the traditional organizational career has proved to be remarkably resilient and announcements of its death have proved to be premature. There have been some shifts in the balance of the exchange that underpins the career, as work-force values shift and increasing numbers of key staff possess transferable knowledge and skills. Successful organizations have found ways of modifying the career exchange to the mutual advantage of the organization and its key staff. As long as they continue to succeed in this, the organizational career will survive.

REFERENCES

Albert, S., Ashforth, B., & Dutton, J. (2000). Organizational identity and identification: Charting new waters and building new bridges. Academy of Management Review, 25, 13–17.

Arnold, J. (1997). Managing careers into the 21st century. London, UK: Sage.

Arnold, J., & Cohen, L. (2008). The psychology of career in industrial and organizational settings: A critical but appreciative analysis. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 23, 1–44.

Arthur, M. (1994). The boundaryless career: A new perspective for organizational inquiry. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 295–306.

Arthur, M., Inkson, K., & Pringle, J. (1999). The new careers: Individual action and economic change. London, UK: Sage.

Arthur, M., & Rousseau, D. (1996). Introduction: The boundaryless career as a new employment principle. In M. Arthur & D. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era (pp. 3–20). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Aydemir, A., & Borjas, G. (2007). A comparative analysis of the labor market impact of international migration: Canada, Mexico and the United States. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5, 663–708.

Barley, S., & Kunda, G. (2004). Gurus, hired guns and warm bodies: Itinerant experts in a knowledge economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17, 99–120.

Barney, J., & Wright, P. (1998). On becoming a strategic partner: Examining the role of human resources in gaining competitive advantage. Human Resource Management Journal, 37, 31–46.

Baron, J., & Bielby, W. (1986). The proliferation of job titles in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31, 561–586.

Baruch, Y., & Peiperl, M. (2000). Career management practices: An empirical survey and implications. Human Resource Management, 39, 347–366.

Borjas, G. (2006). Native internal migration and the labor market impact of immigration. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 221–258.

Bowen, D., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM–performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29, 203–221.

Briscoe, J., & Hall, D. (2006). The interplay of boundaryless and protean careers: Combinations and implications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 4–18.

Briscoe, J., Hall, D., & DeMuth, R. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers: An empirical exploration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 30–47.

Brown, W., Deakin, S., Nash, D., & Oxenbridge, S. (2000). The employment contract: From collective procedures to individual rights. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 38, 611–629.

Cadin, L., Bailly-Bender, A., & Saint-Giniez, V. (2000). Exploring boundaryless careers in the French context. In M. Peiperl, M. Arthur, R. Goffee, & T. Morris (Eds.), Career frontiers: New conceptions of working lives (pp. 228–255). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cappelli, P. (1999). Career jobs are dead. California Management Review, 42, 146–167.

Card, D. (2001). Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local market impacts of higher immigration. Journal of Labor Economics, 19, 22–64.

Carnoy, M., Castells, M., & Benner, C. (1997). Labour markets and employment practices in the age of flexibility: A case study of Silicon Valley. International Labour Review, 36, 27–48.

Chambers, E., Foulon, M., Handfield-Jones, H., Hankin, S., & Michaels, E., III (1998). The war for talent. The McKinsey Quarterly, 3, 44–57.

Combs, J., Liu, Y., Hall, A., & Ketchen, D. (2006). How much do high performance practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Personnel Psychology, 59, 501–528.

Coyle-Shapiro, J., & Conway, N. (2004). The employment relationship through the lens of the psychological contract. In J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. Shore, S. Taylor, & L. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 5–28). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

DeFillippi, R., & Arthur, M. (1994). The boundaryless career: A competency-based perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 307–324.

Eisenberger, R., Jones, J., Aselage, J., & Sucharski, I. (2004). Perceived organizational support. In J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. Shore, S. Taylor, & L. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 206–250). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Evets, J. (2003). The sociological analysis of professionalism. International Sociology, 18, 395–415.

Freeman, C., Soete, L., & Efendioglu, U. (1995). Diffusion and the employment effects of information and communication technology. International Labour Review, 134, 587–603.

Gould, S. (1979). Characteristics of career planners in upwardly mobile occupations. Academy of Management Journal, 22, 530–550.

Guest, D., Isaksson, K., & De Witte, H. (2010). Employment contracts, psychological contracts and employee well-being: An international study. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hall, D. (1976). Careers in organizations. Santa Monica, CA: Scott Foresman & Co.

Hall, D. (2004). The protean career: A quarter-century journey. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 1–13.

Hall, D., & Mirvis, P. (1995). The new career contract: Developing the whole person at midlife and beyond. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47, 269–289.

Harris, R. (2001). The knowledge-based economy: Intellectual origins and new economic perspectives. International Journal of Management Reviews, 3, 21–40.

Hochschild, A. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books.

Ibarra, H. (1999). Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 764–791.

Inkson, K. (2006). Protean and boundaryless careers as metaphors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 48–63.

Jacoby, S. (1999). Are career jobs headed for extinction? California Management Review, 42, 123–145.

Kalleberg, A. (2000). Nonstandard employment relations: Part-time, temporary and contract work. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 341–365.

Khilji, S., & Wang, X. (2006). “Intended” and “implemented” HRM: The missing linchpin in strategic human resource management research. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17, 1171–1189.

King, Z. (2004). Career self-management: Its nature, causes and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65, 112–133.

Knell, J. (2000). Most wanted: The quiet birth of the free worker. London, UK: The Work Institute.

Krugman, P. (1994). Does third world growth hurt first world prosperity? Harvard Business Review, 72, 113–121.

Lambert, L., Edwards, J., & Cable, D. (2003). Breach and fulfillment of the psychological contract: A comparison of traditional and expanded views. Personnel Psychology, 56, 895–934.

Lee, T., Mitchell, T., Sablynski, C., Burton, J., & Holtom, B. (2004). The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences and voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 711–722.

Lepak, D., & Snell, S. (1999). The human resource architecture: Toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Academy of Management Review, 24, 31–48.

Lepak, D., & Snell, S. (2002). Examining the human resource architecture: The relationships among human capital, employment and human resource configurations. Journal of Management, 28, 517–543.

Lepak, D., Takeuchi, R., & Snell, S. (2003). Employment flexibility and firm performance: Examining the interaction effects of employment mode, environmental dynamism, and technological intensity. Journal of Management, 29, 681–703.

Littler, C., Wiesner, R., & Dunford, R. (2003). The dynamics of delayering: Changing management structures in three countries. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 225–256.

Miner, A., & Robinson, D. (1994). Organizational and population level learning as engines for career transitions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 345–364.

Mirvis, P., & Hall, D. (1994). Psychological success and the boundaryless career. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 365–380.

Montes, S., & Irving, G. (2008). Disentangling the effects of promised and delivered inducements: Relational and transactional contract elements and the mediating role of trust. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 1367–1381.

Nicholson, N., & West, M. (1988). Managerial job change: Men and women in transition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

O'Mahoney, S., & Bechky, B. (2006). Stretchwork: Managing the career progression paradox in external labor markets. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 918–941.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2002). Employment outlook. Paris, France: Author.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2006). Employment outlook. Paris, France: Author.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2010). Employment outlook. Paris, France: Author.

Ornstein, S., & Isabella, L. (1993). Making sense of careers: A review 1989–1992. Journal of Management, 19, 243–267.

Osterman, P. (1994). Internal labor markets: Theory and change. In C. Kerr & P. Staudohar (Eds.), Labor economics and market relations: Markets and institutions (pp. 303–339). Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Osterman, P., & Burton, D. (2005). Ports and ladders: The nature and relevance of internal labor markets in a changing world. In S. Ackroyd, R. Batt, P. Thompson, & P. Tolbert (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of work and organization (pp. 425–447). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Pascale, R., & Athos, A. (1981). The art of Japanese management. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Peel, S., & Boxall, P. (2005). When is contracting preferable to employment? An exploration of management and workers perspectives. Journal of Management Studies, 42, 1675–1697.

Peiperl, M., & Baruch, Y. (1997). Back to square zero: The post-corporate career. Organizational Dynamics, 25, 7–22.

Pfeffer, J. (1998). The human equation. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Pfeffer, J. (2001). Fighting the war for talent is hazardous to your organization's health (Stanford University Research Paper No. 1687). Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Pringle, J., & Mallon, M. (2003). Challenges for the boundaryless career odyssey. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14, 839–853.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Rodrigues, R., & Guest, D. (2010). Have careers become boundaryless? Human Relations, 63, 1157–1175.

Roehling, M. W. (2004). Legal theory: Contemporary contract law perspectives and insights for employment relationship theory. In J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. Shore, S. Taylor, & L. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 65–93). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Rosenbaum, J. (1979). Tournament mobility: Career patterns in a corporation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 220–241.

Rousseau, D. (1989). Psychological and implied contracts in organizations. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 2, 121–139.

Rousseau, D. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rousseau, D. (2005). I-deals: Idiosyncratic deals employees bargain for themselves. New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Saxenian, A. (1996). Beyond boundaries: Open labor markets and learning in Silicon Valley. In M. Arthur & D. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era (pp. 23–39). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Schein, E. (1978). Career dynamics: Matching individual and organizational needs. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley.

Shore, L., & Shore, T. (1995). Perceived organizational support and organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano & K. Kazmar (Eds.), Organizational politics, justice and support: Managing social climate at work (pp. 149–164). Westport, CT: Quorum Press.

Smith, V. (1997). New forms of work organization. Annual Review of Sociology, 23, 315–339.

Smola, K., & Sutton, C. (2002). Generational differences: Revisiting generational work values for the new millennium. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 363–382.

Sorensen, J., & Sorensen, T. (1974). The conflict of professionals in bureaucratic organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19, 98–106.

Stahl, G., Miller, E., & Tung, R. (2002). Toward the boundaryless career: A closer look at the expatriate career concept and the perceived implications of an international assignment. Journal of World Business, 37, 216–227.

Sturges, J., & Guest, D. (2001). Don't leave me this way: A qualitative study of influences on the organizational commitment and turnover intentions of graduates early in their career. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 29, 447–462.

Sturges, J., & Guest, D. (2004). Working to live or living to work? Work/life balance early in the career. Human Resource Management Journal, 14, 5–20.

Sullivan, S. (1999). The changing nature of careers: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 25, 457–484.

Sullivan, S., & Arthur, M. (2006). The evolution of the boundaryless career concept: Examining physical and psychological mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 19–29.

Taylor, S., & Tekleab, A. (2004). Taking stock of psychological contract research: Assessing progress, addressing troublesome issues, and setting research priorities. In J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. Shore, S. Taylor, & L. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 312–331). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Tolbert, P. (1996). Occupations, organizations, and boundaryless careers. In M. Arthur & D. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career: A new employment principle for a new organizational era (pp. 331–349). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Van Maanen, J. (1977). Organizational careers: Some new perspectives. New York, NY: Wiley.

Wallace, J. (1995). Organizational and professional commitment in professional and nonprofessional organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 228–255.

Williamson, O. (1975). Markets and hierarchies. New York, NY: Free Press.

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26, 179–201.

Zhao, H., Wayne, S., Glibowski, B., & Bravo, J. (2007). The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: a meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 60, 647–680.