10

Rethinking the Employee–Organization

Relationship: Insights From the

Experiences of Contingent Workers

Daniel G. Gallagher

James Madison University

Catherine E. Connelly

McMaster University

Our understanding of the employee–organizational relationship (EOR) (Coyle-Shapiro, Shore, Taylor, & Tetrick, 2004), as well as other behavioral theories or frameworks related to the employment relationship, is heavily based on the implicit notion of a “standard” employment arrangement (e.g., Ashford, George, & Blatt, 2007; Gallagher & Sverke, 2005; George & Chattopadhyay, 2005; Pfeffer & Baron, 1988; Rousseau, 1997). The EOR draws upon social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) and the inducements–contributions model (March & Simon, 1958) to explain why workers respond to their employers’ actions by engaging in reciprocal behaviors. As such, the EOR forms the foundations of many fundamental theories underlying worker behaviors (e.g., psychological contract, perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, organizational commitment). However, this begs a theoretical and practical question: What if the worker is not an “employee” per se, and what if the employer is potentially a client or even a series of clients, sometimes found through an intermediary?

As noted by Kalleberg (2000), employment has normally been characterized as work that is performed (a) on a full-time basis (e.g., a 35- to 40-hour work week); (b) with an expectation that the employment could continue indefinitely; (c) at the employer's place of business; and (d) under the employer's direction or supervision. It may also be noted that it is inherently accepted that the assorted “standard” workforce of full-time employees, managers, and executives work within a single identifiable “employer” organization (e.g., Western Electric, Canadian Tire, Nokia, IKEA).

The fact that behavioral researchers have built theories and conducted empirical investigations in the context of permanent employment is understandable. First and foremost, the development of organizational behavior as a field of study coincided chronologically with the transition of employment in developed countries to hierarchical organizations with internal labor markets, based on the principles of training, retention, and advancement (Cappelli, 1999; Doeringer & Piore, 1971; Pearce, 1993). Second, for the past few generations of labor force participants, full-time ongoing employment is still the prevailing working arrangement. Third, behavioral research itself tends to originate through scholars who are based at universities and research centers in more affluent and economically developed countries where permanent employment has prevailed.

Today, many organizations have begun to slowly shift away from retention-based staffing toward more transitory contractual arrangements. This strategy has been widely referred to as the “core–periphery” or “core–ring” model (Atkinson, 1984; Gallagher & Connelly, 2008; Handy, 1989). The “core” is comprised of organizational members who can be characterized as permanent employees with “ongoing” attachments to the organization. In contrast, “the periphery” represents workers with varying degrees of affiliation with the organization—those with part-time or temporary fixed-term (i.e., contingent) contracts. The outer edges of the periphery would include the complete outsourcing of functional areas (e.g., payroll, marketing, security, information processing).

Within this broad framework, the objective of this chapter is to examine the EOR through the vantage point of contingent work. More specifically, there is a need to explore the extent to which existing theoretical frameworks, which have been built in permanent employment contexts, are fully applicable to the understanding of contingent work (Rousseau, 1997). Possible peculiarities will be identified with regard to the parties that are involved in the exchange relationship, as well as consideration of what is being exchanged (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). As part of the discussion, we will also consider how well various well-established EOR concepts (e.g., organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, leader–member exchange, and psychological contracts) apply to the various contingent employment arrangements. This chapter also explores the extent to which insights regarding contingent workers’ experiences can help us to understand the attitudes and behaviors of more traditional employees. Some practical suggestions will be offered for workplace application as well as avenues for future research.

DEFINING THE DOMAIN

As noted in the research literature related to contingent work, there is considerable variation in the labels assigned to the different contractual arrangements; several terms are also used to capture the same form of arrangement. In part, much of this labeling is somewhat prescriptive and value driven. As suggested, the use of the term “nonstandard” or atypical assumes the presence of a clearly defined and accepted norm of what is standard or typical. What might be typical employment in Nigeria or the Netherlands might not be typical in Canada or Sweden. As noted by De Cuyper et al. (2007), the proper interpretation of empirical research findings associated with nonstandard and temporary employment arrangements is very much dependent on the ability to have clarity in how the particular forms of nonstandard employment are, in fact, being defined. It is important to emphasize that there is also considerable legal ambiguity about the extent to which contingent workers are attached to or even employed by the organizations with which they are affiliated (Wears & Fisher, 2010).

To achieve the objective of viewing the applicability of EORs in the context of nonstandard employment arrangements, we have chosen to specifically focus on and contrast three different but common examples of what can be termed as “contingent” employment relationships (Connelly & Gallagher, 2004a). This list of contingent employment relationships is not exhaustive, but these three particular forms have been chosen because they represent the diversity of employment structures that are available to organizations and workers. Other work arrangements (e.g., seasonal, casual) are largely analogous to the contingent work relationships that are described next and are therefore not specifically included in our discussion. With all three of these forms of contingent employment there exists a commonality in that these employment relationships are all fixed-term, rather than ongoing, in nature. As such, these forms of contingent work all represent “peripheral” employment relationships, as represented in the Atkinson (1984) core–periphery model.

1. Direct-hire workers: One very common form of contingent employment is where organizations directly recruit and hire workers on fixed-term contracts (Figure 10.1). Often such “direct-hire” workers are employed by an organization to meet predictable seasonal demands for goods and services. Organizations may also go about directly hiring workers (e.g., “lumpers”) on an ad hoc daily basis (Gallagher & Connelly, 2008). One such form of direct-hire work arrangements is “zero-hour” or roster-based employment, where workers are on an on-call basis and are employed and paid only when employers require additional labor on a short-term basis. A familiar example to most of us would be the substitute or “supply” teacher. As with permanent employees, direct-hire workers perform their jobs under the immediate control of the employing organization and at the employer's place of business. However, the work is “precarious” in nature because there is no guarantee of ongoing employment (Gallagher & Connelly, 2008).

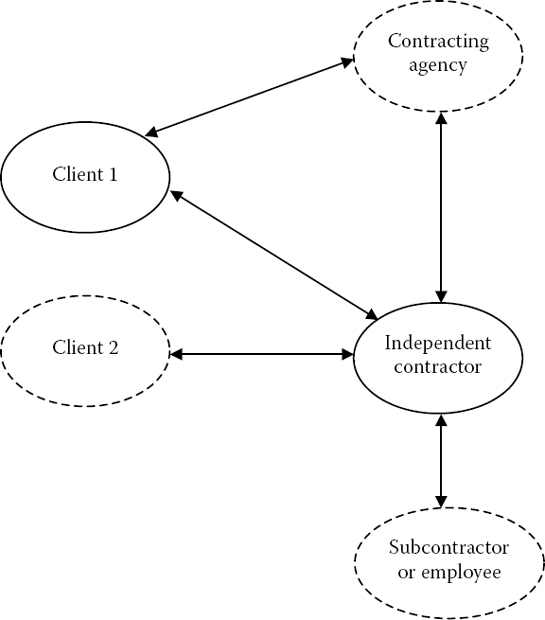

2. Temporary help services: A form of fixed-term work can be found in an organization's use of temporary help services firms or agencies (e.g., Adecco, Ranstand, Manpower) to provide workers on an ad hoc basis (Figure 10.2). As with direct-hire temporary employees, the work performed for the organization is done on a fixed-term contract. However, the work is performed within the organization by a worker who is often legally a nonemployee; the worker is assigned or dispatched by the temporary help firm, but the work itself is actually performed by an assigned temporary worker (i.e., temp) at the location of the client organization (Gallagher & Connelly, 2008).

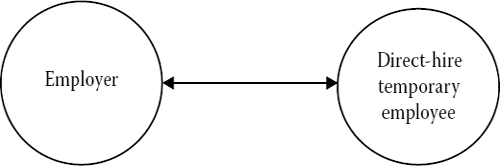

3. Independent contractors: The third form of contingent work that is included in our discussion is that of independent contractors (Figure 10.3). Contracting does not involve an employer–employee relationship, but rather a client–contractor arrangement. In situations where contractors rely on intermediaries to secure clients and manage compensation, the arrangement then becomes more akin to that of a temporary staffing service arrangement (Barley & Kunda, 2004). Independent contracting also assumes that, within parameters, it is the contractor and not management who controls how the work is performed (Church & Lambert, 1993; Connelly & Gallagher, 2006). As noted by McLean Parks, Kidder, and Gallagher (1998), independent contractors also have the unusual distinction of being able to simultaneously contract with multiple client organizations. In many respects, independent contractors are technically “self-employed” and are often legally reported as such, but there are instances where workers’ status may be legally disputed (Wears & Fisher, 2010).

FIGURE 10.1

Direct-hire contingent workers.

FIGURE 10.2

Temporary agency workers.

As a final caveat, it is important to note that workers with these contingent work arrangements may vary in their identification with and acceptance of the conditions of their employment. For example, some direct-hire temporary workers with long service at an organization may consider themselves to be quasi-permanently employed even though the terms of their contracts specify otherwise. Other workers may be unaware of the technical or legal details of their contracts. Together, these factors may contribute to a further “blurring” of the distinctions between the different forms of contingent employment. For the purposes of this chapter, however, each form of contingent work will be treated as distinct, as we discuss how the forms relate to EORs.

FIGURE 10.3

Independent contractors.

CONTINGENT EMPLOYEE–ORGANIZATION RELATIONSHIPS

Much of the early research about contingent workers assumed there was a weak exchange relationship between the worker and the employer or client. For example, contingent workers’ psychological contracts were once said to be necessarily transactional in nature, and it was also originally assumed that contingent workers would not have affective organizational commitment to their clients or engage in organizational citizenship behaviors. Both assumptions have now been shown to be incorrect (Pearce, 1993; Van Dyne & Ang, 1998), but this conjecture of a weak or even nonexistent emotional connection between the worker and the employer was noteworthy because it has formed the bedrock of much of the research in organizational behavior.

Drawing on both social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) and the inducements–contributions model (March & Simon, 1958), the EOR forms the basis for much of the core concepts in organizational behavior (e.g., organizational commitment, perceived organizational support, organizational citizenship behaviors, psychological contracts). Much of the early research about contingent workers’ experiences was drawn primarily on the inducements–contributions model. However, on closer examination, it is apparent that contingent workers do have relationships with their employers and clients, although these relationships are necessarily affected by the workers’ contingent status and unusual employment structures. Following is a detailed discussion of how three different forms of contingent workers experience the EOR.

DIRECT HIRES

As noted in Figure 10.1, the structural aspects of the use of direct-hire contingent workers is generally the same as the traditional EOR, with an identifiable employer organization to which the direct hire has an administrative attachment. The operational difference rests in the fact that, by definition, direct-hire contingent workers have a temporal attachment that is of a fixed duration or an irregular basis. However, it can reasonably be asserted that virtually all aspects of the EOR have relevance and are readily applicable with minor adaptations of existing constructs and measures.

One immediate illustration of this point rests with the extensive amount of research examining the concept of organizational commitment among contingent workers (e.g., Buch, Kuvaas, & Dysvik, 2010; Connelly, Gallagher, & Gilley, 2007; Coyle-Shapiro & Morrow, 2006). Along similar lines, there is no reason to suggest that direct-hire contingent workers do not hold perceptions of perceived organizational support or are incapable of structuring a psychological contract. With regard to the latter point, it would be reasonable to assert that workers on fixed-term contracts might have psychological contracts that are somewhat more transactional in nature, but there is no particular reason to suggest that more relational aspects could not, at times, also be emphasized. The question is the nature of the exchange relationship, not whether an exchange exists.

Given the relevance of the EOR to the study of direct-hire contingent workers, scholars are on fairly safe ground with a “plug-in” strategy that takes social exchange–based theories and applies them to the study of direct-hire temporaries. However, there may be salient aspects of the contingent work experience that moderate or mediate the relationships between various aspects of the EOR. One particular issue that has surfaced in the temporary worker literature is the importance of the extent to which a worker actually prefers to work on fixed-term contracts, as a deliberate alternative to permanent employment. This issue has been referred to as “volition” (e.g., Ellingson, Gruys, & Sackett, 1998) or, more simply, as “reasons” for working contingently (Moorman & Harland, 2002). As one would expect, workers who are in a particular employment arrangement by choice tend to be more satisfied and committed to the work and organizations where they are employed (e.g., De Cuyper & De Witte, 2008).

Closely related to the issue of volition are questions related to the workers’ motivations for applying for and accepting a temporary position within an organization. One motivational factor that might be particularly relevant is the belief that temporary employment (e.g., an internship) will be the doorway into a permanent job within the organization (De Cuyper, Notelaers, & De Witte, 2009). When workers are motivated by the prospect of ongoing employment, they then may be willing to offer greater than expected inputs (e.g., organizational citizenship behaviors) in the hope of future reciprocation in the form of a permanent job. However, a direct-hire temporary worker on a seasonal contract (e.g., summer, holidays) or a temporary worker who is not interested in permanent employment may view the employment relationship as heavily transactional.

At issue is the importance of not treating all forms of contingent work or all forms of direct-hire contingent work as interchangeable; workers’ motivations for choosing a particular form of employment relationship may have important consequences for how the workers frame and interpret the EOR. For example, direct-hire temporary workers who are anticipating a continued relationship with the organization may have higher expectations or sensitivity to how they are treated. Perceived organizational support and justice may interact with a worker's motivations for accepting contingent employment to predict their attitudes (e.g., organizational commitment) and behaviors (e.g., organizational citizenship behaviors).

Interpersonal interactions in organizations are said to be governed by an implicit and unspoken social exchange between coworkers. The underlying facilitator of these interactions is trust (Blau, 1964; Homans, 1958), which generally involves one party willing to be vulnerable to the actions of another, due to positive expectations of the other's intentions, even in the absence of monitoring or third-party controls (Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995; Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, & Camerer, 1998). Interpersonal trust between coworkers is an integral component of effective social exchanges in organizations and has been linked to both task performance and organizational citizenship behaviors (Chou, Wang, Wang, Huang, & Cheng, 2008; Colquitt, Scott, & LePine, 2007).

Most importantly, in the context of contingent work, trust generally needs time to develop; both parties require the opportunity to observe the other's behaviors (Blau, 1964). The implications for the EORs of direct-hire temporary workers, and indeed for all contingent workers, are therefore potentially serious. These workers may not be at the employer or client for sufficient time for them to be trusted by their supervisors or coworkers. As such, they may find that they are assigned simpler tasks that are easier to monitor (Ang & Slaughter, 2001), which may in turn interfere with their career progression. A lack of interpersonal trust may also interfere with the normal social interactions that ordinarily occur in the workplace and the broader EOR.

There may also be instances, however, where the direct-hire temporary worker may believe that they have a more ongoing relationship with the organization than is warranted by their legal contract. In these situations, the interactions between direct-hire contingent workers and permanent employees may become less distant, with the direct hires engaging in trusting behaviors that, if reciprocated, may result in closer interpersonal ties. Conversely, there may also be instances where the organization considers direct hires to be integral and potentially permanent members of the organization (Stamper, Masterson, & Knapp, 2009). For example, large accounting firms often hire summer interns as part of a long-term recruitment strategy, hoping that these recruits will then work for the firm permanently upon graduation. In these cases, the organization and the direct supervisor may treat these contingent workers particularly well and therefore elicit high levels of perceived support, affective organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors.

In summary, the direct-hire contingent worker arrangement is a good starting illustration for the simple reason that this employer–employee relationship is structurally simple. Using Pfeffer and Baron's (1988) measures of externalization, direct-hire contingents are primarily distinct from standard workers on the dimension of temporal attachment and are very much like standard workers with regard to administrative and physical attachment. As suggested, we find that aspects of social exchange theory, developed in the context of standard work arrangements, still have applicability to the study of direct-hire temporaries. What is required is not so much the redevelopment of our established theories, but rather greater attention to issues of volition and motivation for accepting this form of employment versus what is typically discussed in the EORs of permanent employees.

Temporary Agency Workers

In contrast to direct hires, the employment of temporary workers through the use of an intermediary introduces a whole series of theoretical issues that have been beyond the scope of past research pertaining to the EOR. As suggested in Figure 10.2, temporary agency workers have relationships with both an agency and a client, and these relationships are based on an expectation that the worker will be moving from one client to the next. This arrangement is especially interesting from an EOR perspective because the worker is not technically an employee of the organization where the job is performed. As noted by Coyle-Shapiro and Conway (2004), there might well be more parties involved in the EOR than initially envisioned.

From both a practical and theoretical perspective, conventional views toward the EOR might be challenged by the simple fact that a clearly defined employer organization does necessarily exist. As noted by Gallagher and McLean Parks (2001), for temporary help service workers, the fundamental term “organizational commitment” can be confusing. Some workers might assess organizational commitment in terms of the client where they perform their work, whereas others might view the employer as the firm that arranges their placement and signs their paycheck. Given that workers can have multiple foci of commitment, the challenge of measuring temporary worker attitudes (e.g., commitment, perceived organizational support) in this context relates to the need to reconsider how attitude is measured as well as the extent to which client and agency attitudes are interrelated, most notably the degree to which attitudes toward the client are influenced by attitudes to the agency and vice versa (e.g., Connelly et al., 2007; Coyle-Shapiro & Morrow, 2006; Buch et al., 2010). Two such applications of behavioral spillover are organizational citizenship behaviors (Liden, Wayne, Kraimer, & Sparrowe, 2003) and counterproductive work behaviors (Connelly & Gallagher, 2004b).

Similar to direct-hire workers, research on temporary help service–based contingent workers involves a consideration of the importance of both volition and motivation in the understanding of how such workers evaluate their client and agency “employment” relationship. A preference for permanent employment might influence the behaviors such workers have toward the client and agency. As suggested in Figure 10.2, these workers often move from assignments in one client organization to another. From a theoretical perspective, this would suggest that client-based attitudes and the nature of the psychological contracts may change as workers move between assignments. As such, agency-based workers may be particularly prone to contrast effects; the evolution of their EOR might be readily influenced by prior client experiences.

One further aspect of the EOR that has relevance to temporary agency workers and other contingent workers is the issue of time. Many of the aspects of the employer–employee relationship that have been examined by behavioral researchers have assumed that relationships can strengthen or weaken over time. This point has been well demonstrated in the case of psychological contracts and relationships with supervisors and coworkers (e.g., leader–member exchange). As with direct-hire temporary workers, temporary agency workers may face barriers to being trusted by their supervisors and coworkers because of the relatively short duration of their contracts. However, as per social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), contingent workers who are affiliated with an agency may also be particularly prone to being considered as outsiders by the permanent employees with whom they work.

One exception to the lack of trust invested in contingent workers, and temporary agency workers in particular, is the phenomenon of “swift trust” (Kasper-Fuehrera & Ashkanasy, 2001; Meyerson, Weick, & Kramer, 1996; Rousseau, 1997). In instances where the temporary agency worker is part of a profession and has been contracted to play a circumscribed role with which the other team members are familiar (e.g., anesthesiologist, accountant), the other organizational members may engage in swift trust. Indeed, the temporary worker's professional commitment, rather than their commitment to their agency or client, may facilitate this process. Temporary agency workers who demonstrate appropriate professional values (e.g., patient care) will more likely be perceived as trustworthy by their new colleagues. It should be noted, however, that swift trust is fragile; once broken, it may be difficult to rebuild (Tomlinson & Mayer, 2009).

There has been a significant level of interest in how the EOR plays out when there is a joint employer or more than one client (Connelly et al., 2007; Coyle-Shapiro & Morrow, 2006). For example, the temporary agency worker may need to develop separate employment relationships with the agency or intermediary as well as several different client organizations. Together, these results suggest that more adapted constructs are needed that are specific to the temporary agency worker context and that capture the complexity inherent in this relationship. For example, it is perhaps more nuanced to refer to a temporary agency worker's attitudes as perceived client support and perceived agency support, rather than as perceived “organizational” support. Similarly, one might refer to agency commitment or client commitment instead of “organizational” commitment, and agency or client justice rather than “organizational” justice. This nomological evolution is somewhat similar to that seen in the literature on perceived union support and union commitment (Gordon, Philpot, Burt, Thompson, & Spiller, 1980; Shore & Tetrick, 1991; Shore, Tetrick, Sinclair, & Newton, 1994). The differentiation between temporary agency workers’ commitments to different organizations (i.e., the agency and the client) will enable researchers to determine whether these workers prioritize their relationships with one organization over another, how these relationships are interrelated, and what factors affect these relationships.

As an aside, a competing theory that is sometimes used to explain workers’ motivations and behaviors in organizations is “agency theory” (Eisenhart, 1989). This theory is predicated on the assumption that workers behave in ways that advance their own interests and that the best way to motivate appropriate behavior is to align workers’ interests with those of the organization (e.g., introduce profit-sharing plans). Temporary agency workers are therefore a particularly interesting subset of workers to study, in that they provide an illustration of how agency theory cannot fully explain worker behavior because the workers’ interests will never be fully aligned with both the agency and the client organization. By definition, the interests of the two organizations are always going to be potentially in conflict. For example, a client will want the assigned tasks to be completed as efficiently as possible (i.e., quickly and with high quality), and the temporary agency will prefer that the assignment generate as much revenue as possible (i.e., speed is not a priority).

Independent Contractors

Of the three broad forms of contingent employment being addressed in this discussion, the status of independent contractors or freelancers is potentially the most complex from a structural and definitional perspective. This complexity is due in part to the fact that independent contracting arrangements can change over time. In its most simple form, independent contracting involves a direct relationship between an individual and a client organization predicated on exchange of particular services for an agreed project or time-based rate. Most importantly, unlike a direct-hire temporary, a true independent contractor is, in most countries, outside the legal definition of “employee.” As suggested in Figure 10.3, an independent contractor may work with one client at a time or work simultaneously with multiple clients. Once again referencing Pfeffer and Baron's (1988) levels of detachment, independent contractors tend to be at the outer limits of the core–periphery workforce model. First, although hope may exist for a long-term relationship, these work arrangements are legally fixed term. Second, true “independent” contracting vests administrative control with the independent contractor. Finally, whether or not the work is actually performed “on site” is negotiable rather than required.

Although technically the exchange relationship is not between an employee and an organization, exchanges between independent contractors and clients are an important, yet underrecognized, part of the employment landscape. At the most immediate level is the aforementioned exchange of labor (knowledge and skills) for compensation. Such a contractor–client relationship could be viewed as purely transactional. However, as noted by Barley and Kunda (2004), many independent contractors are highly reliant on the ability to attract and retain clients. As a result, it is possible to suggest that the psychological contract with the supervisor at the client organization may broaden over time, as the contractor endeavors to elicit more favorable treatment by engaging in instrumentally motivated extracontract behaviors.

In contrast to temporary agency workers, who are often able to rely on their agencies to procure a series of client assignments, independent contractors usually are responsible for finding their own patrons, either through the extension of a current contract, the renewal of a previous client (e.g., semiannual updating of a website), or positive word-of-mouth that results in a new contract with a new organization. This unique structure, coupled with the fact that independent contractors have fewer legal protections than employees, has implications for the contractor–client relationship, in that independent contractors may be motivated to perform additional tasks (e.g., work overtime not specified in the contract) in the hopes that this will lead to favorable treatment by the client. The resultant dynamic may be different than social exchange because it is not mutual and the underlying intention is instrumental (i.e., to receive additional contracts in the future). Indeed, this aspect of independent contractors’ EOR bears more similarity to the inducements–contributions model, although it is enacted somewhat differently than usually conceptualized because the contractor (nonemployee) rather than the organization is the party offering the inducement to receive the added contribution. However, if the relationship continues, the power differential is mitigated (e.g., by both parties being equally dependent on the other), and trust develops sufficiently, then there is a possibility that this relationship could become more of a social exchange.

The fact that independent contractors may be working with a series of clients suggests that the nature of the exchange relationship may differ on a client-by-client basis. Unlike most psychological contracts research, as it generally applies to traditional or single-employer relationships, many contractors are dealing with the possible need to enter into idiosyncratic exchanges with each client organization. Contractor behaviors may be focused not only on client retention, but also on the exchange of services and accommodations with the expectation that such action will be further rewarded by client recommendations and support in securing other opportunities. In effect, what might be generally viewed as primarily economic transactions may evolve into more relational and supportive exchanges over time.

Independent contractors are similar to direct-hire temporary workers in that both types of work involve fixed-term contracts. However, independent contractors are perhaps more similar to temporary agency workers in that there is likely to be a series of clients and client organizations. Indeed, one of the legal requirements of independent contracting in most countries is that the worker is not solely dependent on a single client organization, lest this firm become a de facto employer (Fragoso & Kleiner, 2005). An additional similarity with temporary agency workers arises from the fact that independent contractors sometimes find work through an intermediary.

As noted in Figure 10.3, there are two optional structural characteristics of independent contracting that further contribute to the complexity of exchange relationships in the context of independent contracting. The first is that independent contractors may choose to use a series of contracting agencies in the task of seeking to secure clients. Under such circumstances, independent contract work more closely begins to represent the triangular relationship found in the temporary agency work form of contingent employment. As a result, the contractors’ exchange focus extends beyond that of the client organization and involves the contracting agency as well as the other exchange-related issues previously discussed.

Second, an often overlooked aspect of independent contracting and related exchange relationships is the circumstance where the contractor hires workers to provide support services. In such instances, the contractor also assumes a second identity as that of an employer organization. In doing so, there is now the injection of an EOR, which even on a small operational scale fits well with the existing volume of knowledge pertaining to employment relationships. Conversely, rather than embark on an employer–employee relationship, the independent contractor may choose to build his or her own peripheral workforce through the subcontracting of support services (e.g., accounting, marketing, etc.). Such a strategy would again take the business arrangement outside of the traditional EOR.

As is the case with other contingent work arrangements, understanding the attitudes and behaviors of independent contractors requires a consideration of these workers’ volition and motivations (Evans, Kunda, & Barley, 2004; Kunda, Barley, & Evans, 2002). For some workers, the decision to work as an independent contractor may be the result of a lack of traditional employment opportunities, for example, as witnessed by the growing number of workers who have been terminated from their traditional jobs and rehired by the organization as “independent” contractors. The latter case is particularly interesting for the reason that such a transfer of status might not only be involuntary but may also represent to the worker a breach of the preexisting psychological contract. As such, the contractor–client relationship might well be one that operates in an environment of varying levels of trust or distrust.

As with the direct-hire and temporary agency workers previously discussed, it is possible that independent contractors may not work with the organization long enough for interpersonal trust to develop between the contractor and the permanent members of the organization. However, in many instances, independent contractors working at a client organization have a prior employment relationship with the firm. For example, it is not uncommon for an entire department to be “outsourced” or have their employment terminated while an offer of contract work is simultaneously offered (Ho, Ang, & Straub, 2003). Furthermore, many retirees periodically continue working on contract as a form of “bridge employment” that allows them to enjoy some of the advantages of being employed (e.g., social contact, remuneration, a feeling of meaningfulness) with added flexibility (Kim & Feldman, 2000). In these instances, the EOR is likely to be affected by the prior relationship; these independent contractors may have higher expectations for how they will be treated compared with truly independent contractors who have had no prior connection.

In some instances, organizations may become dependent on the services of a particular contractor. For example, the contractor may have expertise or social connections that are unusually rare (e.g., a retired employee who is the only remaining person alive who understands a “legacy” information technology [IT] system, a former politician who is now acting on behalf of a company as a lobbyist). In these cases, the EOR will be affected by the atypical power imbalance between the two parties; the contractor will be able to request preferential treatment over and above what would be expected by an employee.

Finally, an often overlooked component of the “independent” contracting experience that may impact the contractor–client relationship is the level of dependency that the contractor has on the client organization as a source of work. As noted by Connelly and Gallagher (2006), contractors are sometimes heavily reliant on a single client; rather than handling multiple contracts simultaneously, they hope to have their existing contract renewed indefinitely. In these cases, the EOR is again imbalanced; dependent contractors must be on their “best behavior” lest they not have their contracts renewed. It is also difficult for them to demand better treatment, given that they may have few alternative employers and given that the client may have several alternative employees.

RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS

Thus far, the focus of contingent worker research has been on how theories developed in the context of permanent employment can be used to explain contingent workers’ attitudes and behaviors and to explain why these workers’ experiences differ from those of employees with permanent employment contracts. Although this research is of intrinsic value (Ashford et al., 2007), it may also be fruitful to consider ways in which theories that have been developed in the context of contingent work can be applied to further understanding the experiences of more permanent employees.

One such construct is that of “volition,” or the extent to which a worker has voluntarily chosen this form of employment. As noted earlier, this construct has been widely applied to contingent workers and especially to temporary agency workers. However, volition could also be helpful in explaining the attitudes and behaviors of standard or permanent workers. For example, early career entrants may accept jobs that are not in their preferred field of choice (e.g., in sales instead of product development) if they feel they have few viable alternatives and believe that the work experience would be useful. This volition, or lack thereof, may affect the worker's EOR, in a pattern similar to the experiences of contingent workers.

In a similar vein, more emphasis can be devoted to research on the impact of multiple affiliations among permanent employees. For example, a salesperson may be committed to one client, while being relatively indifferent to another one. In this case, both client relationships might affect the worker's attitudes toward the employer. Similarly, it is possible that workers who frequently change jobs (e.g., “job hoppers”) may experience attitudinal spillover in that their experiences with one employer may affect their attitudes and behaviors at the next. In these instances, there is more complexity in the EOR than that which would normally be captured with standard measures or cross-sectional research designs.

Despite the recent popularity in research about contingent workers, there are several avenues for research that remain relatively unexplored. For example, given the legal and conceptual similarities between independent contracting and individuals who are self-employed, it may be useful to attempt to reconcile the contingent worker and entrepreneurship literatures. Within the entrepreneurship literature, it may also be useful to apply some of the theoretical advances from research about contingent workers. For example, we now distinguish between different types of nonstandard and contingent workers (e.g., independent contractors versus temporary agency workers); similar distinctions may be made between different types of entrepreneurs.

Although much research exists to explain how personality relates to occupational choice, little research has examined how personality affects broader employment preferences such as the decision to work contingently. One exception is Kolvereid (1996), who has suggested that personality predicts whether an individual will become an entrepreneur or seek employment in an organization. However, much of the existing research about contingent workers has either examined the influence of situational factors (e.g., difficulty finding permanent employment) or ignored the issue altogether. Research is needed to identify how personality and other individual differences affect the likelihood of pursuing contingent work, as well as the preference for one type of contingent work (e.g., independent contracting) over another (e.g., direct-hire temporary work).

One situational factor that has received relatively little attention is the potential impact of industry-wide social norms in moderating contingent workers’ job insecurity (e.g., Ashford et al., 2007). For example, in some industries, contingent workers may be less likely to experience the same amount of job insecurity or anxiety because this form of employment may be relatively common, either as a “rite of passage” on the way to permanent employment or as a viable substitute for it. These industry-wide social norms may affect contingent workers’ EORs if they heighten or reduce their expectations of how the employer should behave or the consequences of having a fixed-term contract end.

In many respects, one can argue that the distinctions between contingent workers and “traditional” forms of work (i.e., permanent employment) are becoming increasingly less rigid. As noted by Stamper et al. (2009), all organizational members may be viewed as having different “profiles” (i.e., peripheral, associate, detached, and full) based on the rights and responsibilities that are assigned to and assumed by the worker. As noted by Stamper et al., both permanent and contingent workers may have these profiles, depending on the specific experiences of the individual. For example, highly skilled contract workers or permanent employees may be classified as “detached” from the organization. These workers’ organizational membership profiles in turn affect their needs as well as whether they believe that these needs are being fulfilled, thereby affecting discretionary and task performance. This theoretical framework is particularly relevant because it includes contingent workers within its conceptualization of organizational members and because it suggests that researchers consider the circumstances of each worker as an individual, rather than as being indistinguishable from his or her employment status. Future research can further consider how such frameworks can similarly encompass both contingent workers and permanent employees.

CULTURAL INFLUENCES

As previously noted, it is important to consider legal variations in how contingent work contracts are stipulated around the world (De Cuyper et al., 2007). In different countries, contingent work arrangements have varying levels of security, stability, and prestige. However, these legal definitions and contextual nuances are often disregarded when research findings are aggregated.

There may also be important cultural differences that will affect how contingent workers experience the EOR. As noted by Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan (2010), the human participants in much of the world's behavioral research studies are “WEIRD,” in that they live in societies that are Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic. Much of the research about contingent workers has been conducted in this context, with the exception of a recent study by Ituma and Simpson (2009). These authors found that contingent workers in Nigeria have a somewhat different focus in terms of the factors they consider when deciding to accept certain jobs; they emphasize ethnic allegiances and personal connections more than Europeans, Australians, and North Americans.

National culture may also play an important role in workers’ interest in accepting contingent work arrangements or in workers’ preferences for certain types of contingent work. For example, workers with high levels of individualism may be more accepting of independent contracting, whereas people in more collectivist countries may prefer being permanent employees or perhaps direct-hire contingent workers. Future research, with nationally diverse participants, can elucidate these possible differences while taking into account the previously noted differences in the legal definitions of these employment arrangements (e.g., a “temporary agency worker” in Sweden is not legally equivalent to one in Canada).

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

Based on the available research about contingent workers’ experiences, it appears that human resources practices may affect the development of an effective EOR between the client (or employer), agency (if applicable), and worker.

At the organizational level, there may be human resource policies that affect how the EOR between the contingent workers and the organization begins; how the relationship is initiated may have long-range effects on its nature and quality. Although many firms use contingent workers specifically to avoid many of the human resources responsibilities that a workforce entails, the engagement of any worker requires some basic groundwork. For example, if the client does not have a prior working relationship with a suitable contractor or temporary worker, the client may choose to work with an intermediary. The temporary agency or contractor's association may then simply send a worker who is (a) available and (b) matches a general description submitted by the client. Alternatively, the client may interview and then select one of a subset of workers who have been nominated by the agency. At the other extreme, some clients recruit and select an appropriate worker but arrange for the payroll to be handled by the agency. The extent of the involvement of the agency and the client has likely implications for the closeness that the worker feels toward each organization.

From the worker's point of view, much more research is needed to identify how contingent workers can best manage their careers. Thus far, there is very little empirical research about how social networks can influence the recruitment and selection of contingent workers, both from the organization's perspective (i.e., finding qualified workers) and the worker's point of view (i.e., securing a steady stream of adequately remunerative and interesting contracts). Future research can specifically examine how social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn) can exacerbate or mitigate the challenges inherent in coordinating contracts.

There is a similar paucity of practitioner-focused research that examines how individuals who are pursuing a “boundaryless” career can effectively balance the positive and negative aspects of different forms of contingent work and permanent employment when they choose a career path. For example, what are the trade-offs involved for early-career entrants who accept a temporary position where the assigned tasks are challenging but there is no internal opportunity for advancement versus a permanent position with less challenge and more security? Advocates of boundaryless careers would suggest that “employment” security accrued through the honing of extensive social networks and up-to-date and in-demand skills will eventually be more valuable than employment offering more traditional job security (e.g., through seniority or a unionized workplace), but longitudinal research is required to see if this bears out.

A related issue that warrants further examination is how workers at various career stages can successfully transition into independent contracting. Many laid-off workers are encouraged to “become their own boss” (witness the old joke: What do you call an unemployed manager? A consultant!), but it is not clear how many are able to use the full set of their abilities and earn a similar salary to what they previously earned. It is equally important to study the process by which temporary workers transition to permanent employment.

From a practitioner standpoint, much remains to be determined in terms of “best practices” or prescriptive guidelines on how to actually manage contingent workers’ EORs. An important aspect for managers to consider is the potential for the presence of contingent workers to affect the EORs of the permanent employees who work alongside them because there is some evidence that the presence of contingent workers leads to an increase in permanent employees’ withdrawal behaviors (Davis-Blake, Broschak, & George, 2003; Way, Lepak, Fay, & Thacker, 2010).

Managers need to appreciate that the presence of contingent workers may mean that the job design of the permanent employees will need to be adjusted (Ang & Slaughter, 2001) and should anticipate that these employees’ attitudes to the employer are likely to change as well. Permanent employees who are taking on additional tasks may feel a sense of injustice if they do not believe that they are fully compensated for these efforts. However, these added responsibilities may represent an opportunity for some permanent employees to improve the quality of their relationships with their supervisors, thereby increasing their leader–member exchange. The additional tasks may also create a more fluid sense of job responsibilities and help to foster a more relational psychological contract.

Because there has been some suggestion that contingent workers are, at times, treated unfairly (Boyce, Ryan, Imus, & Morgeson, 2007; Connelly, Gallagher, & Webster, 2011), there is a possibility that permanent employees who observe such treatment will view their employers negatively. Compared with contingent workers, permanent employees generally have more positive views of their organizations, with more relational psychological contracts (Coyle-Shapiro & Kessler, 2002) and higher levels of affective organizational commitment (Van Dyne & Ang, 1998). However, because people will take into account how well others are treated when they assess the fairness of their own treatment (e.g., Lind, Kray, & Thompson, 1998), positive EORs may be threatened if permanent employees observe that their contingent colleagues are treated unfairly.

CONCLUSION

As noted by Coyle-Shapiro et al. (2004), the EOR is fundamental to our understanding of worker attitudes and behaviors in organizations. However, it is important to recall that not all workers in organizations are employees in the traditional sense. Indeed, a growing cadre of contingent workers (i.e., direct hires, temporary agency workers, independent contractors) is changing how we conceptualize what is meant by “employment” and “organizations” and how workers relate to both. Fortunately, a deeper understanding of the complexities inherent in contingent worker EORs will help us to understand the experiences of all workers, including those of permanent employees.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Karen Bennington for her assistance.

REFERENCES

Ang, S., & Slaughter, S.A. (2001). Work outcomes and job design for contract versus permanent information systems professionals on software development teams. MIS Quarterly, 25, 321–350.

Ashford, S. J., George, E., & Blatt, R. (2007). Chapter 2: Old assumptions, new work. The Academy of Management Annals, 1, 65–117.

Atkinson, J. (1984). Manpower strategies for flexible organizations. Personnel Management, 16, 28–31.

Barley, S. R., & Kunda, G. (2004). Gurus, hired guns, and warm bodies: Itinerant experts in a knowledge economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

Boyce, A. S., Ryan, A. M., Imus, A. L., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Temporary worker, permanent loser? A model of the stigmatization of temporary workers. Journal of Management, 33, 5–29.

Buch, R., Kuvass, B., & Dysvik, A. (2010). Dual support in contract workers’ triangular employment relationships. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 93–103.

Cappelli, P. (1999). The new deal at work. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Chou, L.-F., Wang, A.-C., Wang, T.-Y., Huang, M.-H., & Cheng, B.-S. (2008). Shared work values and team member effectiveness: The mediation of trustfulness and trustworthiness. Human Relations, 61, 1713–1742.

Church, P. H., & Lambert, K. R. (1993). Employee or independent contractor? Management Accounting, 74, 52–55.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 909–927.

Connelly, C. E., & Gallagher, D. G. (2004a). Emerging trends in contingent work research. Journal of Management, 30, 959–983.

Connelly, C. E., & Gallagher, D. G. (2004b, August). Temporary workers, permanent consequences: Behavioral implications of triangular employment relationships. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Meeting, New Orleans, LA.

Connelly, C. E., & Gallagher, D. G. (2006). Independent and dependent contracting: Meaning and implications. Human Resource Management Review, 16, 95–106.

Connelly, C. E., Gallagher, D. G., & Gilley, K. M. (2007). Organizational commitment among contracted employees: A replication and extension with temporary workers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 326–335.

Connelly, C. E., Gallagher, D. G., & Webster, J. (2011). Predicting temporary workers’ behaviors: Justice, volition, and spillover. Career Development International, 16, 178–194.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Conway, N. (2004). The employment relationship through the lens of social exchange. In J. A.-M. Coyle-Shapiro, L. M. Shore, M. S. Taylor, & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 5–28). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Kessler, I. (2002). Contingent and non-contingent working in local government: Contrasting psychological contracts. Public Administration, 80, 77–101.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Morrow, P. C. (2006). Organizational and client commitment among contracted employees. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 416–431.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., Shore, L. M., Taylor, M. S., & Tetrick, L. E. (2004). The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900.

Davis-Blake, A., Broschak, J. P., & George, E. (2003). Happy together? How using nonstandard workers affects exit, voice, and loyalty among standard employees. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 475–485.

De Cuyper, N., de Jong, J., De Witte, H., Isaksson, K., Rigotti, T., & Schalk, R. (2007). Literature review of theory and research on the psychological impact of temporary employment: Towards a conceptual model. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10, 25–51.

De Cuyper, N., & De Witte, H. (2008). Volition and reasons for accepting temporary employment: Associations with attitudes, well-being, and behavioural intentions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17, 363–387.

De Cuyper, N., Notelaers, G., & De Witte, H. (2009). Transitioning between temporary and permanent employment: A two-wave study on the entrapment, the stepping stone and the selection hypothesis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 67–88.

Doeringer, P. B., & Piore, M. J. (1971). Internal labor markets and manpower analysis. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath & Company.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14, 57–74.

Ellingson, J. E., Gruys, M. L., & Sackett, P. R. (1998). Factors related to the satisfaction and performance of temporary employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 913–921.

Evans, J. A., Kunda, G., & Barley, S. R. (2004). Beach time, bridge time, and billable hours: The temporal structure of technical contracting. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 1–38.

Fragoso, J. L., & Kleiner, B. H. (2005). How to distinguish between independent contractors and employees. Management Research News, 28, 136–149.

Gallagher, D. G., & Connelly, C. E. (2008). Nonstandard work arrangements: Meaning, evidence, and theoretical perspectives. In J. Barling & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 621–640). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Gallagher, D. G., & McLean Parks, J. (2001). I pledge thee my troth… contingently: Commitment and the contingent work relationship. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 181–208.

Gallagher, D. G., & Sverke, M. (2005). Contingent employment contracts: Are existing employment theories still relevant? Journal of Economic and Industrial Democracy, 26, 181–203.

George, E., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2005). One foot in each camp: The dual identification of contract workers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 68–99.

Gordon, M. E., Philpot, J. W., Burt, R. E., Thompson, C. A., & Spiller, W. E. (1980). Commitment to the union: Development of a measure and an examination of its correlates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 479–499.

Handy, C. (1989). The age of unreason. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83.

Ho, V. T., Ang, S., & Straub, D. (2003). When subordinates become IT contractors: Persistent managerial expectations in IT outsourcing. Information Systems Research, 14, 66–86.

Homans, G. C. (1958). Social behavior as exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 63, 597–600.

Ituma, A., & Simpson, R. (2009). The boundaryless career and career boundaries: Applying an institutionalist perspective to ICT workers in the context of Nigeria. Human Relations, 62, 727–762.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Nonstandard employment relations: Part-time, temporary and contract work. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 341–365.

Kasper-Fuehrera, E. C., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2001). Communicating trustworthiness and building trust in interorganizational virtual organizations. Journal of Management, 23, 235–254.

Kim, S., & Feldman, D. C. (2000). Working in retirement: The antecedents of bridge employment and its consequences for quality of life in retirement. Academy of Management Journal, 6, 1195–1210.

Kolvereid, L. (1996). Organizational employment versus self-employment: Reasons for career choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Spring, 23–31.

Kunda, G., Barley, S. R., & Evans, J. (2002). Why do contractors contract? The experience of highly skilled technical professionals in a contingent labor market. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55, 234–261.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Kraimer, M. L., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2003). The dual commitments of contingent workers: An examination of contingents’ commitment to the agency and the organization. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 609–625.

Lind, E. A., Kray, L., & Thomson, L. (1998). The social construction of injustice: Fairness judgments in response to own and others’ unfair treatment by authorities. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75, 1–22.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. (1958). Organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

McLean Parks, J., Kidder, D. L., & Gallagher, D. G. (1998). Fitting square pegs into round holes: Mapping the domain of contingent work arrangements onto the psychological contract. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 697–730.

Meyerson, D. E., Weick, K. E., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Swift trust in temporary groups. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 166–195). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Moorman, R. H., & Harland, L. K. (2002). Temporary employees as good citizens: Factors influencing their OCB performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 17, 171–187.

Pearce, J. L. (1993). Toward an organizational behavior of contract laborers: Their psychological involvement and effects on employee co-workers. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1082–1096.

Pfeffer, J., & Baron, N. (1988). Taking the workers back out: Recent trends in the structures of employment. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 257–303.

Rousseau, D. M. (1997). Organizational behavior in the new organizational era. Annual Review Psychology, 48, 515–546.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404.

Shore, L. M., & Tetrick, L. E. (1991). A construct validity study of the survey of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 637–643.

Shore, L. M., Tetrick, L. E, Sinclair, R. R., & Newton, L. A. (1994). Validation of a measure of perceived union support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 971–977.

Stamper, C. L., Masterson, S. S., & Knapp, J. (2009). A typology of organizational membership: Understanding different membership relationships through the lens of social exchange. Management and Organization Review, 5, 303–328.

Standing, G. (2009). Work and occupation in a tertiary society. Labour and Industry, 19, 49–72.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall.

Tomlinson, E. C., & Mayer, R. C. (2009). The role of causal attribution dimensions in trust repair. Academy of Management Review, 34, 85–104.

Van Dyne, L., & Ang, S. (1998). Organizational citizenship behavior of contingent workers in Singapore. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 692–703.

Way, S. A., Lepak, D. P., Fay, C. H., & Thacker, J. W. (2010). Contingent workers’ impact on standard employee withdrawal behaviors: Does what you use them for matter? Human Resource Management, 49, 109–138

Wears, K. H., & Fisher, S. L. (2010, August). Who is an employer in the triangular employment relationship? Sorting through the definitional confusion. Paper presented at Academy of Management Meeting in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.