16

Employee–Organization

Relationship in Older Workers

Mo Wang

University of Maryland

Yujie Zhan

Wilfrid Laurier University

Demographic projections have shown that by 2012, nearly 20% of the total U.S. workforce will be age 55 or older, up from just under 13% in 2000, leading to a sizable increase in the number of people who will transition into retirement in the next decade (Toossi, 2004). Similarly, 41% of the Canadian working population is expected to be between the ages of 45 and 64 by the year 2021 (Lende, 2005). In the United Kingdom, 30% of workers are already over 50 (Dixon, 2003). These labor force change patterns are also demonstrated by data from other countries and regions (e.g., European Union, Japan, China, and India; Tyers & Shi, 2007), reflecting the fact that the population as a whole is getting older due to several factors, such as the aging of the large Baby Boom generation, lower birth rates, and longer life expectancies (Alley & Crimmins, 2007). Consequently, organizations have to consider older workers’ unique characteristics and career development needs when they develop policies and practices to promote the employee–organization relationship (EOR). Given that older workers may expect different types of obligation from the organization compared to younger workers and may use their perception of the EOR to inform mid and late career-related decisions (e.g., early retirement or bridge employment), studying the EOR from the older workers’ perspective is extremely important.

To our knowledge, however, few previous studies have investigated EORs among older workers. As such, the existing theories for EOR, such as social exchange theory and the inducements–contributions model, have not been calibrated for applications to older workers. Specifically, although the theoretical mechanisms and principles specified in these theories may hold across older and younger workers, they may be manifested through different constructs that are age specific. Therefore, the purpose of this chapter is to integrate the aging literature with the EOR literature to provide an understanding of EORs for older workers.

To understand the EOR among older workers, we first discuss the meaning of aging to the EOR. Given the different characteristics, needs, and values of older employees from younger employees, we consider what types of benefits or resources received from organizations may be particularly valued by older workers. We also consider what the unique types of reciprocation are that organizations may receive from older workers. In the second half of this chapter, we examine the relationship between EORs and unique career outcomes for older workers, such as retirement intention and decision, early retirement, and bridge employment.

THE MEANING OF AGING TO THE EOR

The EOR literature has drawn upon social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) and the norm of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), as well as the inducements–contributions model (March & Simon, 1958), to provide the theoretical basis for understanding the employee and employer exchange relationship. Although the exact focus of these theories may vary, a common theme that emerges in these theories is that EORs can be conceptualized as a resource exchange between the organization and the employee. As such, to understand the meaning of aging to the EOR, it is necessary to take a developmental perspective to analyze the potential changes in terms of the resources that older workers expect from their organizations and the resources that they may offer to their organizations as they age. Specifically, the impact of aging on EORs may depend on the impact of the aging process on employees’ physical and mental abilities, work-related functions and activities, and needs and values (Jex, Wang, & Zarubin, 2007; Shultz & Wang, 2008).

The change of the reciprocal relations between older workers and organizations can also be understood from the person–environment (PE) fit perspective. PE fit refers to the congruence or alignment between characteristics of individuals and those of their environment or organization. Fit is dynamic rather than static in nature (Ostroff, Shin, & Feinberg, 2002). As suggested by Feldman and Beehr (2011), older workers may experience a decline of PE fit due to their changes in cognitive ability, physical health, and values. However, the PE fit could be maintained for older workers if their organization implements policies and practices tailoring to older workers’ characteristics and needs. The organization itself may also benefit from such implementation given the unique contribution that older workers potentially make.

EOR Benefits Valued by Older Workers

The typical benefits employees may receive from their organizations include, but are not limited to, economic/material benefits, informational benefits, time benefits, and social–emotional benefits (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Tsui, Pearce, Porter, & Tripoli, 1997). For older workers, four types of resources provided by organizations may be especially valued: aging-related task redesign and training, health care benefits and support, socioemotional support, and family friendly practices.

Aging-Related Task Redesign and Training

As people age, they are exposed to an increasing array of threats to their performance, many of which could be avoided or minimized through improved job design (Fisk & Rogers, 2001). To enhance the EOR for older workers, organizations may want to implement work setting changes that facilitate the performance of older workers. Such implementations can be understood in terms of physical and cognitive aging.

Research has shown a general trend toward decreasing energy and, as a result, reduced capacity for physically demanding tasks with increasing age. For example, with aging, there is a gradual loss of muscle mass and muscle strength, which decreases the maximal exercise capacity (McArdle, Vasilaki, & Jackson, 2002). Aging is also accompanied by the loss of bone tissue throughout the body. Lower bone density may be a risk factor for degenerative arthritis (Sowers, 2001), which is the leading cause of disability among older adults within industrialized countries. Further, metabolism drops as people grow older. With increasing age, mitochondria produce less adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the body's main metabolic source of energy (Jex et al., 2007). The implication is that age-related physical changes may make it more difficult for older workers to perform physically demanding tasks. As such, organizations may promote the EOR by protecting older employees from job tasks that require workers to perform very quickly or require workers to perform physically demanding activities for long periods of time.

In addition to the decline of physical strength, when people grow older, even though their general knowledge remains stable or even increases, they tend to experience a reduction in perceptual and cognitive resources (Fisk & Rogers, 2001; Park, 2000). Specifically, perceptual limitations of older people mainly include vision changes and hearing loss, which may constrain many basic job activities, such as reading and driving. Cognitive aging features declines in processing speed, working memory, inhibition function, and sensations. For example, Salthouse (1996) pointed out that one of the factors accounting for age-related decline in cognitive performance was a general slowing of processing speed of mental operation with aging. Similarly, older adults’ working memory capacity (defined as the amount of online cognitive resources that provide simultaneous storage and processing of information) declines, making it more difficult to perform cognitive tasks requiring both processing and storing information (Park, 2000). Hasher and Zacks (1988) also found that, with aging, people have more trouble inhibiting their attention to irrelevant information and concentrating on relevant information, which makes it difficult for older adults to perform tasks that require long periods of mental concentration. Overall, the cognitive aging literature suggests that age-related reduction in cognitive resources may lead to more difficulty for older workers in dealing with high mental load tasks (Shultz, Wang, Crimmins, & Fisher, 2010; Wang & Chen, 2004, 2006).

In this background of physical and cognitive aging, organizations may facilitate EORs by benefiting their older employees via implementing task redesigns to make work settings friendlier for older workers as well as providing training to help them take advantage of new technologies to assist their work (Fisk & Rogers, 2001). For example, organizations are recommended to protect their older employees by avoiding memory demands through provision of familiar cues and minimizing irrelevant or distracting information from work instructions. Applications of new technology (e.g., enterprise resource planning systems) may also relieve workers from excessive information processing by organizing and automating routine productive processes, thereby decreasing the cognitive load imposed on workers. In addition, organizations may want to provide more breaks for older workers to relieve them from the potential negative effects of performing cognitively intense tasks.

Health Care Support

Among the various issues related to aging, health is always viewed as one of the most critical concerns because people are more likely to face health issues during their later life. With physical aging, workers’ health care may become an important part of the employment relationship. Entering the 21st century, health care costs have been increasing rapidly in United States, as has the cost for health insurance coverage. Therefore, EORs for older workers may be greatly influenced by the quality of health care benefit provided by the organization, because it has important implications for both older workers’ physical and financial well-being.

In addition to health care benefits, organizations may promote the EOR by protecting their older employees from occupational hazards. As people age, they are more vulnerable to threats to their health and safety. For example, research evidence suggests that older adults’ immune systems take longer to build up defenses against specific diseases. As a result, older adults become more prone to serious consequences from illnesses that are easily defeated by young adults (Aldwin & Gilmer, 1999). This translates to risks in performing job tasks that may involve exposure to chemicals, being struck by heavy objects, exposure to violence, and repetitive motions. Given the vulnerability of older workers, organizations may implement safety and health care practices to minimize the threats to older employees. In addition, medical care related to schedule flexibility at work may also be greatly valued by older workers.

Socioemotional Support

According to the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory (SST), a basic awareness of passage through different life stages is ubiquitous in all cultures and people, which has implications for people's motivations (Carstensen, 1991). SST also posits that individuals are typically agentic in that they set goals and behave in ways that are likely to help them achieve those goals (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999). Put together, these two principles indicate that where one is in his or her “lifetime” strongly shapes the types of goals an individual will pursue. Specifically, SST posits that when an individual is younger, he or she is closer to the beginning of his or her life cycle and thus views “time” as time since birth. Thus, his or her goals will be future oriented: He or she will aim toward knowledge acquisition, career planning, and the development of new social relationships that will pay off in the future (Carstensen, 1991). Older individuals, by contrast, view “time” as time left in life. Thus, they will have more present-oriented goals: They aim toward regulating their emotions to be positive, pursuing emotionally gratifying relationships with others, and engaging in activities that will benefit them relatively immediately (Carstensen, 1991). Overall, according to SST, older adults focus more on socioemotional outcomes, whereas younger adults are more driven by skill, knowledge, and opportunity development and, thus, are more information oriented. Given the focus of older adults on socioemotional outcomes, EORs may play a more important role in older workers’ job satisfaction and well-being. EOR literature has shown that social exchange is associated with socioemotional outcomes such as trust, loyalty, and affective commitment (Shore, Coyle-Shapiro, Chen, & Tetrick, 2009; Shore, Tetrick, Lynch, & Barksdale, 2006). Compared to economic exchange, socioemotional support provided by organizations may be perceived to be more valuable for older workers.

Although little research has examined SST in the workplace, several studies do suggest that age-related differences in goals and motivations do manifest themselves in organizational settings. For instance, research has suggested that older workers are less career development oriented and often avoid challenges at work, whereas younger adults tend to have a “learning orientation” and thus use challenges as learning and development opportunities (Kanfer & Ackerman, 2004). In addition, research has shown that compared to older employees, younger employees are typically more competitive rather than cooperative (Wong, Gardner, Lang, & Coulon, 2008), and older adults typically display more affective commitment to their organization, whereas younger employees tend to place more importance on “employability” and opportunity for advancement (D'Amato & Herzfeldt, 2008).

Given that older workers may put more value on regulating their emotions to be positive and pursuing emotionally gratifying relationships with others, organizations should promote a more cooperative and less political work climate among employees. Further, older workers may prefer not to face too many new challenges, especially those of evaluative nature, at the workplace. Accordingly, organizations should pay attention to how they conduct performance evaluation and provide feedback to older workers. When it comes to a feedback event, older workers may be more affected by the quality of the feedback delivery rather than the content of the feedback. As such, interactional justice at the workplace may play an important role in facilitating EORs in older workers. Finally, employment security is obviously preferred by older workers.

Family-Friendly Practices

At present, more and more couples enter the labor force at the same time, creating a large number of dual-earner families. When it comes to older workers, one issue that features the particular need for work–family balance is care-giving responsibility. In today's workforce, the number of workers caring for family members at both ends of the life span—children and elders—is growing quite rapidly. These workers are often referred to as the sandwich generation (Neal & Hammer, 2007). Several social and demographic trends have contributed to the phenomenon of the sandwich generation in the United States, including delayed childbearing, the aging of the American population, the aging of the American workforce, the increasing number of women in the workforce, decreases in family size and changes in family composition, and rising health care costs. Neal and Hammer (2007) found that members from the sandwich generation preferred jobs that allow flexibility either in one's daily work schedule or where the work is performed in order to be able to provide family care. Moreover, members from the sandwich generation also prefer working for organizations that have family-friendly policies so that they can attend to their family care needs.

Given that the typical age of the sandwich generation members ranges from 40 to 55 years, these preferences in terms of jobs and organizations are likely to substantially influence EORs for older workers. Organizations may promote EORs for older workers by providing flexible time schedules that allow people to select their work hours, thereby giving employees flexibility to attend to child and/or elder care needs. Organizations may also set up family leave programs to provide paid or unpaid time off for family issues, such as illness of spouse, children, or parents.

EOR Benefits Offered by Older workers

The typical benefits organizations may receive from their employees include, but are not limited to, productivity, organizational citizenship behaviors, and loyalty (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Tsui et al., 1997). Although these benefits generally apply to employees across different ages, the unique characteristics of older workers, and their experience and expertise in particular, may change the specific types of contributions they can make.

Experience and Expertise Enhanced by Aging

One thing that we know typically occurs as people age is that they gain experience and often have higher levels of task-related expertise. As one would probably imagine, experience is typically associated with higher levels of work performance. Experience and expertise are also important when complex tasks are performed at work. Although it has been shown that older workers do have more difficulty on physically and cognitively demanding tasks, there have also been studies showing no age-related difference in the performance of such tasks. Scholars have suggested that older employees with higher levels of task-related expertise are able to develop strategies to compensate for their physical and cognitive declines without impairing their task performance. As such, experience and expertise are particularly useful for older workers to continue their careers without having to make a career path change or exit.

Given the experience and expertise of older workers, they may contribute to the EOR not only through their own skilled performance but also through their roles as mentors for younger coworkers. For example, Dendinger, Adams, and Jacobson (2005) have shown that an important work motivation for older workers is to pass their knowledge and skills to younger generations (i.e., generative motivation). Therefore, for organizations, nurturing older workers’ expertise and providing them autonomy and opportunities to actively apply it to their work may be important ways to promote EORs in older workers. It may be good for organizations to set up a formal mentoring system that fulfills older workers’ generative motivation.

Summary

Aging has particular meanings to the EOR between older workers and their organizations. Beyond the typical benefits and resources involved in the exchange relationship, organizations’ obligations to older workers should emphasize aging-friendly work settings, health care benefits and support, socioemotional support, and family-friendly practices. Reciprocally, older workers with extensive experiences are valuable resources for organizations. Also, older workers are the experts who are more motivated to pass their knowledge and skills to younger generations.

Consistent with the reciprocal nature of EORs, according to the PE fit perspective, a reciprocal fulfillment between person and job may prompt employees’ job performance and/or psychological well-being. For older workers in particular, although declined cognitive and physical ability may threaten their ability–demand fit in accomplishing some tasks, their experience, expertise, and generative motivation could potentially offer opportunities for fulfilling other job demands such as mentoring. In addition, need–supply fit can be promoted by organizations that take care of older workers’ values and needs. It should be noted that few studies have directly examined EORs for older workers, which renders a lack of empirical findings in this area. Future research needs to empirically test the factors theorized here and confirm their roles in promoting positive EORs for older workers.

EORS AND RETIREMENT

Literature has shown that EORs may impact individuals’ job-related decision-making process. For older workers, one of the most important career decisions they have to make relates to retirement. As a type of work withdrawal behavior, retirement would occur in different forms sooner or later in one's career life. As such, older workers’ decisions regarding when to retire and how to retire could be impacted by EORs. However, because of the aging of the workforce, retirement has become an inevitable issue for organizations. Organizations may strategically influence older workers’ retirement process through retirement-related human resource management (HRM) practices that are closely related to EORs.

In this section, we discuss the linkage between EORs and retirement from the perspectives of both older workers and organizations. We believe taking both perspectives will contribute to our understanding of the EOR–retirement relationship because it reflects the two streams of concerns in EOR research and retirement research. First, further improvement in EOR research requires the consideration of both parties in the relational system (e.g., Coyle-Shapiro & Shore, 2007). As indicated in other chapters of this volume (e.g., Chapter 12), although EOR research has largely been based on social exchange theory (e.g., Coyle-Shapiro & Conway, 2004; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Shore & Shore, 1995), “research on social exchange is very rarely ‘social’ in the sense that it seeks to incorporate both parties’ perspectives to the exchange” (Coyle-Shapiro & Conway, 2004, p. 22); instead, previous literature on the EOR tended to focus on only one party's perception, in particular employees’ perceptions of organizations, such as perceived organizational support and psychological contracts. Therefore, researchers are recommended to involve employees and organizations as well as their interaction in examining the EOR (e.g., Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Shore et al., 2004).

Second, retirement can be viewed as a mutual withdrawal of older workers and their organizations (Adams, Prescher, Beehr, & Lepisto, 2002). It does not exclusively depend on employees’ attitudes. In recent literature, retirement has been increasingly conceptualized in multiple ways (Wang & Shultz, 2010). Two conceptualizations, retirement as decision making and retirement as a part of HRM, are especially relevant to EOR research, capturing the perspectives of employees and organizations. The first conceptualization views retirement as a motivated choice behavior of older workers. By making the decision of retirement, employees choose to decrease their psychological commitment to work and behaviorally withdraw from work (Adams et al., 2002; Shultz & Wang, 2008). According to a decision-making model of retirement (Feldman, 1994), organizational factors, especially EOR-related factors (e.g., organizational commitment, perceived organizational support), compose an important set of variables that influence employees’ intention and actual decision of retirement. Another conceptualization of retirement concerns organizations’ retirement-related HRM practices. Accordingly, organizations are able to manage retirement by designing appropriate HRM practices in order to strategically reach their goals (Wang & Shultz, 2010). Retirement policies and practices, such as early retirement incentives and offering retirement counseling programs, may impact retirement decisions as an important part of EORs for older workers.

Given the dual emphasis on both employees and organizations in both EOR and retirement literature, we organize this section by first discussing the role of EOR in influencing employees’ retirement intentions and decisions. We then describe how retirement-related HRM practices may influence older workers’ EORs. We draw on social exchange theory as the primary theoretical background.

EOR and Retirement Intentions and Decisions

For individuals, retirement decisions involve a complex evaluation of work, personal, and financial issues. Feldman (1994) has proposed a theoretical model of retirement decision making, defining retirement as an exit taken by older workers from workplaces with a decreased commitment to work thereafter. In Feldman's model, organization-related factors have been explicitly included as a set of antecedents of retirement decision functioning above and beyond traditionally tested demographic information and individual health and wealth.

The quality of the EOR is a part of the decision-making process about retirement. In general, positive perception of EORs may postpone employees’ retirement due to three possible reasons. First, social exchange theory suggests that employees who perceive a highly beneficial EOR may feel obligated to reciprocate their organizations by increasing their work input (Coyle-Shapiro & Conway, 2004; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005), which may be translated into longer working life for older workers. By contrast, negative perception of EORs may lead to more intention of retirement. Once older workers perceive their organizations to be less supportive and even discriminating against older workers, they will be more likely to withdraw from their organizations as a means of reciprocating to organizations’ withdrawal from older workers.

Second, accompanied with the prolonged working life, older workers who perceive highly beneficial EORs may expect better treatment from organizations when they approach retirement. Older workers who are approaching retirement age tend to compare their working status with their expected postretirement life. On the one hand, they value their work role identity; on the other hand, they expect less demands and more personal time during retirement. Compared with older workers with unpleasant relationships with their organizations, workers with more positive EORs are more likely to expect more supportive systems from their organizations, such as flexible work schedules and respect for older workers. Therefore, positive EORs may encourage older workers to continue working in their organizations by satisfying the older workers’ expectation of reduced work commitment without losing their work role identity.

Third, older workers may postpone retirement simply because they enjoy working in their organizations. With a higher level of emotional attachment to and identification with the organization, older workers are likely to be willing to stay in their organization for a longer time. In the following sections, we present empirical evidences for the relationship between two EOR indicators, perceived organizational support and organizational commitment, and older workers’ retirement intentions and decisions.

Perceived Organizational Support

For employees, the organization serves as an important resource of tangible benefits such as wages and medical benefits, as well as socioemotional support such as respect and caring. Employees who form a positive perception concerning the organizational support would feel attached to their organization and obligated to help the organization reach its goals. In turn, they would expect improved performance to be rewarded (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchinson, & Sowa, 1986; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002).

Although perceived organizational support has been shown to be negatively related to absenteeism (Eisenberger et al., 1986) and turnover (Baranik, Roling, & Eby, 2010), there is a lack of empirical work directly examining the effect of perceived organizational support in impacting older workers’ retirement intention. However, different literatures have paid attention to organizational factors that may impact older workers’ retirement through studying perceived socioemotional support from organizations. For example, in some organizations, older workers may face discrimination and negative stereotypes because of possible decline in work capability (Posthuma & Campion, 2009). Experiences of being discriminated against could push older workers out of their employment. For example, Zappala, Depolo, Fraccaroli, Guglielmi, and Sarchielli (2008) tested the effect of firm aging norms in predicting postponing retirement. Their results showed that older workers tended to retire late if the management team in their company displayed special attention to maintain the employability of elderly employees and the supervisors took into account their age, health, and capacity when assigning tasks and conduct evaluations. The effect of aging norms may be explained by a heightened level of perceived organizational support. For older workers, their perceived organizational support is expected to be particularly sensitive to age-related discrimination and negative stereotype. Accordingly, respect and consideration of management teams and supervisors may effectively increase older workers’ perceived support.

Organizational Commitment

Organizational commitment is closely related to perceived organizational support and can be viewed as individual perception of the organization's commitment to an employee (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). According to social exchange theory, employees are prone to exchange their commitment for an employer's support (Eisenberger et al., 1986). Many empirical studies have been conducted to examine the relationship between organizational commitment and retirement-related outcomes, such as early retirement intention (e.g., Gaillard & Desmette, 2008), retirement intention (e.g., Adams & Beehr, 1998; Adams et al., 2002), and planned retirement age (e.g., Taylor & Shore, 1995). The effect size of organizational commitment is small to moderate, but organizational commitment is usually a significant predictor of retirement after controlling for individual characteristic variables such as age, personal finances, and health. Furthermore, organizational commitment has been shown to predict retirees’ bridge employment intentions. According to a recent empirical study (Jones & McIntosh, 2010), although organizational and occupational commitment both predicted retirement intention, a stronger predictive effect was found for organizational commitment than occupational commitment in predicting bridge employment in the same organization.

Among the studies mentioned above, the commitment construct is typically operationalized by measuring older workers’ affective commitment. Nevertheless, researchers have begun to explore the potential differences between specific forms of commitment in impacting retirement decision (e.g., Jones & McIntosh, 2010; Luchak, Pohler, & Gellatly, 2008). For example, Luchak et al. (2008) examined the effects of affective commitment and continuance commitment on planned age of retirement under a defined-benefit pension plan. According to commitment theory, individuals’ motivation to stay is experienced as a mind-set that varies depending on the perceived reasons of stay. Specifically, working is a personal choice due to enjoyment for employees with higher levels of affective commitment, whereas working is a necessity to avoid social and economic adversity for employees with higher levels of continuance commitment. Luchak et al. (2008) showed that affective commitment was positively associated with planned age of retirement, whereas a curvilinear relationship was found between continuance commitment and planned retirement age such that employees who had higher levels of continuance commitment tended to retire at the age when their pension benefit reached maximum. As such, the positive effect of affective commitment reflects the emotional reason for stay versus retirement, and the curvilinear effect of continuance commitment reflects the cognitive benefit–cost calculation in the retirement decision-making process.

Economic Exchange

In addition to the influences of sociopsychological exchange relation on retirement, economic exchange also impacts one's decision of retirement. Financial issues are critical to retirement decisions (Wang, Henkens, & van Solinge, 2011). People are more likely to retire when they can afford it. Older workers with financial constraints are expected to be especially sensitive to economic exchange with their organization. For instance, a defined-benefit pension plan is a type of pension plan in which an employer promises a specified monthly benefit on retirement that is predetermined by a formula based on the employee's earnings history and work tenure. Under this plan, older workers tend to retire at the time point when their pension income is maximized (Luchak et al., 2008). A defined-contribution pension plan refers to the retirement plan in which the amount of the employer's annual contribution is specified and retirement benefit fluctuates on the basis of investment earnings. This type of plan provides employees more control and flexibility and is usually viewed as more motivating.

It is necessary to point out that the relationship between the EOR and retirement intentions and decisions is not exclusively negative. Similar to previous findings that demonstrate inconsistent associations between EORs and turnover (see Chapter 15 of this volume), we expect that the impact of EORs on retirement intentions/decisions may also vibrate due to the different strategic goals of organizations. In particular, positive EORs may lead to an increased rather than decreased tendency to retire if organizations strategically encourage employees’ retirement. With a more positive EOR, older workers may also tend to expect a satisfying retirement package from their organizations. Therefore, we expect a pleasant retirement process for older workers retiring from organizations with which they have positive relationships. In the next section, we discuss in detail EORs and retirement-related HRM practices.

EORs and Retirement-Related HRM Practices

Within HRM research, Wright, McMahan, and McWilliams (1994) proposed that firms’ human resources (HR) practices would shape human capital pool and elicit employee behaviors in line with firm goals. Ostroff and Bowen (2000) further emphasized the role of HRM practices as critical determinants of employee perceptions and behavior that would facilitate organizational effectiveness. Accordingly, retirement-related HRM practices are particularly important indicators of organizations’ investment and support to older workers, which may influence the quality of employment relation and employees’ attitudes toward their organization.

For organizations, the removal of a compulsory retirement age has introduced uncertainty about staff profiles and financial burden for HR planning. It also requires individuals to take a more active and strategic role in their own retirement planning (Bidewell, Griffin, & Hesketh, 2006). Indicating organizations’ investment in EOR, retirement-related HRM practices may serve two different strategic purposes (Wang & Shultz, 2010). First, HRM can be viewed as a subsystem that exchanges resources with the environment to attract, develop, motivate, and retain human capital in order to ensure the effective functioning of the organization (Jackson & Schuler, 1995). By designing appropriate practices providing financial benefits (e.g., generous pension benefit and postretirement medical care benefit) or sociopsychological support (e.g., retirement counseling program [e.g., Shuey, 2004] and mentoring opportunity), organizations are able to show their consideration of older workers and promote positive EORs, resulting in employees’ increased commitment to the organization and delayed retirement. Second, HRM may also serve organizations’ strategic goals of human capital restructuring or downsizing. Via HRM practices, such as early retirement incentive package (Feldman, 2003) and phased retirement policy (e.g., Greller & Stroh, 2003), organizations invest in the exchange relationships in order to support older workers’ withdrawal.

Early Retirement Incentives

In retirement literature in the 1990s when “many organizations were seeking to improve their competitiveness through global manufacturing relocation or outsourcing peripheral services” (Wang & Shultz, 2010, p. 180), one of the most popular retirement-related HRM practices was early retirement incentives. According to Feldman (2003), organizations have much control over the financial incentives offered, but the valence of such incentives varies across organizations with different pension policies (e.g., defined-contribution or defined-benefit pension plan) and workers with different characteristics.

Bidewell et al. (2006) applied the delay discounting perspective to explain the effect of early retirement incentives. According to this perspective, time usually results in a subjective devaluation of the later reward, causing people to prefer a small but early reward to avoid the potential loss during waiting. Further, devaluation of the delayed reward is much greater when the early reward can be collected immediately than when there is a long time to wait before the availability of the early reward. In this scenario, early retirement incentive can be viewed as the small but early reward provided to older workers who are approaching their eligibility to maximized Social Security and pension benefit. Therefore, by providing appropriate early retirement incentives, organizations demonstrate their support to older worker retirement. As shown by Bidewell et al. (2006), retirement age is negatively related to the discounting amount. In addition, early retirement incentives may be accompanied by the organizational support of early retirement counseling program. Because the early retirement decision is usually surrounded by considerable uncertainty and the feeling of involuntariness, a comprehensive preretirement counseling program may help to reduce the ambivalence (Feldman, 1994), as well as the feeling of involuntariness that might be triggered by early retirement (Szinovacz & Davey, 2005).

Bridge Employment Opportunity

When Baby Boomers’ retirement starts to lead to labor force shortages, bridge employment will become an increasingly popular research topic (Wang & Shultz, 2010). Bridge employment refers to paid employment taken by older workers after exiting positions or career paths of considerable duration and before their complete work withdrawal (Shultz, 2003). Because older workers are a skilled and experienced workforce, organizations that need to maintain flexible access to such a workforce should communicate their value and provide opportunities for continued work in retirement.

Providing bridge employment opportunity for older workers may also be a good way for organizations to show their commitment to older workers’ needs and well-being. For one reason, past studies have shown that many older workers may have not amassed sufficient resources to achieve a desired standard of living at the time they retire (Hershey, Jacobs-Lawson, McArdle, & Hamagami, 2007). In this situation, an opportunity of bridge employment provided by their employers is highly valuable for one's financial transition. Further, previous studies have shown that bridge employment helps retirement transition and adjustment (Kim & Feldman, 2000; Wang, 2007). To mitigate the negative feeling of work role loss, retirees are likely to appreciate a bridge job that helps them to maintain work role identity, social contact, and life pattern. Continued working may increase the perceived organizational membership of retirees, which is a representation of the overall general EOR. Further, Zhan, Wang, Liu, and Shultz (2009) found that bridge employment, especially bridge employment in the same career field as before the retirement, was beneficial for retirees’ physical and mental health.

In addition to the needs for financial income, social contacts, and work role identity, a unique reason for older people to work is to pass their knowledge and skills to younger generations (Dendinger et al., 2005). An organization can help older workers to pursue the generative meaning of work by developing mentoring systems embedded in bridge employment that may encourage retirees to mentor and share knowledge with younger workers. These practices not only help older people gain continuity between working and retirement, but also help organizations maintain a flexible access to an experienced workforce as well as smooth the knowledge transfer process from one generation of workers to another.

Given the unique functions of bridge employment, it can be viewed as a special type of EOR for older workers. Applying the meaning of aging to EOR we discussed earlier, bridge jobs are expected to be designed with full consideration of age-related changes in terms of physical and cognitive ability, values, and preferences. Organizations may recruit retirees for certain positions that typically require less physical effort but more professional experiences and expertise, and they reciprocate to reemployed retirees with socioemotional support such as opportunities for promoted sense of self-worth and social acceptance, as well as opportunities to pass their knowledge and skills to younger generations.

Integrating the Organization's and Employee's Perspectives

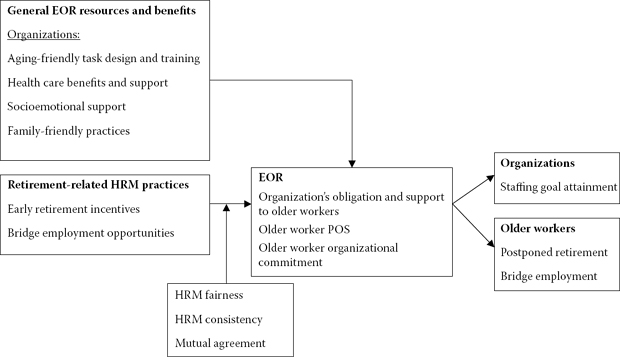

So far, we have discussed the role of EORs on employees’ retirement and organizations’ management of EORs through retirement-related HR practices. We now propose a mediation model where the retirement-related HR practices and policies are expected to increase the perceived quality of the EOR, which, in turn, will align employees’ retirement decisions with organizations’ strategic goals for the workforce (Figure 16.1). Specifically, for older workers, their perception of organizations’ resources, practices, and policies provides them information to evaluate organizations’ concern and commitment to older workers. Reciprocating to organizations’ favorable treatment and expecting more benefit in the future, older workers may increase their work effort by postponing retirement or engaging in bridge employment. For organizations, they design HR practices that are consistent with organizational strategic goals and deliver these practices to employees, which may contribute to the formation of a shared positive perception regarding EORs such that the employer is considerate and supportive. Consequently, a positive EOR increases employees’ work well-being and helps organizations to achieve their staffing or downsizing goals.

Nonetheless, several issues need to be discussed regarding the mediating role of EORs between HR practices and retirement. First, the mediation model presented here focuses on a top-down process in which the organization has much control over the development of the EOR. However, EORs can also be developed in a bottom-up process in which employees observe and communicate with each other to infer and attribute the organizations’ commitment to their relationship with employees. Employees’ perceptions of EORs are not independent of each other for those working in the same organization or work unit; neither is the retirement decision. Coworkers’ retirement could prompt others to retire or think about retirement. Observing or hearing about coworkers’ unpleasant interaction with the organization may ruin the EOR quality for others. Consequently, employees may be less confident in the mutual exchange relationship with the organization. In general, if employees are not exposed to consistent HR practices, it is possible for them to form various perceptions of EORs (Takeuchi, Wang, Marinova, & Yao, 2009). If the EOR perception developed by employees working in the same organization varies across a wide range, it is less likely for the organization to achieve its strategic goal by actively managing its relationship with employees. Therefore, organizations’ HR practices should be designed and delivered with full consideration of fairness and consistency (see Figure 16.1; Bowen & Ostroff, 2004). For example, organizations should make sure that all employees are aware of and able to access the resources offered to them. A retirement planning program might be particularly helpful in facilitating communication and seeking feedback.

FIGURE 16.1 The mediation role of EOR in older worker–related organizational staffing and retirement decision-making. HRM, human resources management; POS, perceived organizational support.

Second, an underlying assumption in most EOR literature is the mutual agreement between organization and employees of the obligations to each other. However, the two parties do not always agree on the EOR (Shore et al., 2004). Shore et al. (2004) discussed three potential sources of the discrepancies in EOR perceptions: divergent schemata of the employee and employer, the complexity and ambiguity around employment contracts, and miscommunication between the two parties. Given the discrepancy in their understanding of EORs, employees may have difficulties in recognizing the organization's investment in their relationship. At the same time, the organization's practices could not be transferred to corresponding employees’ retirement decisions consistent with the organization's strategic goal.

Third, related to the different understanding of EOR by each party, employees and organizations may have a different evaluation of how the other party has fulfilled their obligations. The divergent perceptions will inevitably produce misunderstanding and contract breach. Bennett, Tetrick, Ginter, and McCausland (2010) have applied the unfolding model of turnover to understanding the retirement decision process. According to their model, when an older worker who expects certain rewards for postponing retirement suddenly realizes that his or her organization will not meet this expectation, he or she is likely to experience the violations to his or her values and benefits. Consequently, a retirement decision path may be activated.

Finally, Kuvaas (2008) proposed an alternative model to explain the role of the EOR such that the quality of the EOR can moderate the relationship between perception of HR practices and employee outcomes. Specifically, when workers perceive an organization's efforts to provide more resources as motivated by self-interest rather than by genuine concern for employees, an organization's HR practices could not lead to positive work outcomes. Supporting this contingency perspective, Tsui et al. (1997) found that employee responses differed under different types of relationships based on the relative investment of organizations. When applied to understand the EOR and retirement relationship, this contingency perspective suggests that when older workers have positive perceptions regarding their relationship with their organization, they are more likely to view the retirement-related HR practices as an organization's investment to improve employees benefit or well-being and to reciprocate to such investment by making more efforts. Therefore, a high-quality EOR may be necessary for older workers to be motivated to respond positively to retirement-related practices in a way that will benefit the organization.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this chapter is to integrate the aging and retirement research literature with the EOR literature to provide an examination of EORs among older workers. It should be noted that the approach taken here is more illustrative rather than exhaustive. Given that few previous studies have investigated EORs among older workers, we contend that our theoretical integration here suggests ways to calibrate theoretical frameworks of EORs for applications to older workers. In particular, when discussing the meaning of aging to the EOR, we emphasized the specific resources exchanged between older workers and the organization, as well as the aspects important for older workers to reach PE fit. When discussing the relationship between EORs and older workers’ retirement decisions, we also strived to reach a theoretical balance by drawing perspectives from both older workers and the organizations. Nevertheless, our theoretical development is limited by the social exchange mechanism and the norm of reciprocity. According to Cropanzano and Mitchell (2005), social exchange is one process that leads to the establishment and sustainability of a relationship, but not the only one. Future studies should consider other processes for EOR to form and how they may lead to different implications for older workers.

It should also be noted that culture may be an important boundary condition to consider EORs among older workers. In different societal cultures, older workers may develop different needs and value different things. For example, in Eastern societies heavily influenced by Confucianism, such as Chinese and Japanese societies, older age is typically associated with seniority and higher social hierarchies (Li, Tsui, & Weldon, 2000). Therefore, older workers in those societies may be more sensitive to whether the organization's HR practices demonstrate sufficient respect to them. Such respect may not only be associated with the materialized support they receive from the organization, but also the “good faces” (i.e., positive views from others) they gain from the organization's practice. For example, older workers in those societies may particularly value the opportunity for them to participate in company policy making, even though such practice is only a type of formality (Li et al., 2000). Given that older workers from different cultures may value different resources and benefits they receive from organizations, cultural factors should also be included in considerations when examining EORs in older workers. To our best knowledge, no empirical studies have examined the potential joint effect of culture and age on EORs, which may point to a fruitful future research direction.

This chapter has important practical implications. First and foremost, both employees and organizations should be aware of the age-related physical and cognitive changes and actively manage the reciprocal relation between older employees and organizations to promote EORs. For organizations, they need to recognize the advantages of older employees who have more professional experience and expertise as well as a high generative motivation to deliver their knowledge to colleagues. Also, given the characteristics, values, and preferences of older workers, organizations are recommended to focus more on the health care benefits of older employees, socioemotional support, and family-friendly practices. Second, organizations with specific staffing goals with older workers can take advantage of EORs by implementing retirement-specific HRM practices. On the one hand, organizations that plan to retain older employees are recommended to design appropriate practices providing an older worker–friendly workplace in order to show their consideration of older workers and promote positive EORs. On the other hand, organizations with downsizing plans may implement retirement-supportive practices such as early retirement incentive packages and phased retirement policies. In addition, organizations should pay attention to whether a mutual agreement is established regarding the meaning of EORs for older employees. Third, in the decision-making process about retirement and bridge employment, older workers should take into account the quality of EORs. Considering their declined ability in certain areas and unique motivation for working after retirement, older workers are recommended to assess the organizations’ resources, practices, and policies to evaluate the organizations’ commitment to older employees.

REFERENCES

Adams, G. A., & Beehr, T. A. (1998). Turnover and retirement: A comparison of their similarities and differences. Personnel Psychology, 51, 643–665.

Adams, G. A., Prescher, J., Beehr, T. A., & Lepisto, L. (2002). Applying work-role attachment theory to retirement decision-making. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 54, 125–137.

Aldwin, C. M., & Gilmer, D. F. (1999). Immunity, disease processes, and optimal aging. In J. C. Cavanaugh & S. K. Whitbourne (Eds.), Gerontology: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 123–154). New York: Oxford University Press.

Alley, D., & Crimmins, E. (2007). The demography of aging and work. In K. S. Shultz & G. A. Adams (Eds.), Aging and work in the 21st century (pp. 7–23). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum & Associates.

Baranik, L. E., Roling, E. A., & Eby, L. T. (2010). Why does mentoring work? The role of perceived organizational support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76, 366–373.

Bennett, T. M., Tetrick, L., Ginter, R., & McCausland, T. (2010, April). Applying job embeddedness and the unfolding model of turnover to understand the retirement decision process. Paper presented at the 25th Annual Society for Industrial/Organizational Psychology Conference, Atlanta, GA.

Bidewell, J., Griffin, B., & Hesketh, B. (2006). Timing of retirement: Including delay discounting perspective in retirement model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 368–387.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. (2004). Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29, 203–221.

Carstensen, L. L. (1991). Selectivity theory: Social activity in life-span context. In K. W. Schaie (Ed.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Vol. 11, pp. 195–217). New York, NY: Springer.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A.-M., & Conway, N. (2004). The employment relationship through the lens of social exchange. In J. A.-M. Coyle-Shapiro, L. M. Shore, M. S. Taylor, & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 5–28). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Coyle-Shapiro, J. A-M., & Shore, L. (2007). The employee-organization relationship: Where do we go from here? Human Resource Management Review, 17, 166–179.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900.

D'Amato, A., & Herzfeldt, R. (2008). Learning orientation, organizational commitment and talent retention across generations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23, 929–953.

Dendinger, V. M., Adams, G. A., & Jacobson, J. D. (2005). Reasons for working and their relationship to retirement attitudes, job satisfaction and occupational self-efficacy of bridge employees. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 61, 21–35.

Dixon, S. (2003). Implications of population ageing for the labour market. Labour Market Trends, 111, 67–76.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchinson, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507.

Feldman, D. C. (1994). The decision to retire early: A review and conceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 19, 285–311.

Feldman, D. C. (2003). Endgame: The design and implementation of early retirement incentive programs. In G. A. Adams & T. A. Beehr (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, processes, and results (pp. 83–114). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Feldman, D. C., & Beehr, T. A. (2011). A three-phase model of retirement decision-making. American Psychologist, 66, 193–203.

Fisk, A. D., & Rogers, W. A. (2001). Health care of older adults: The promise of human factors research. In W. A. Rogers & A. D. Fisk (Eds.), Human factors interventions for the health care of older adults (pp. 1–12). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Gaillard, M., & Desmette, D. (2008). Intergroup predictors of older workers’ attitudes toward work and early exit. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 17, 450–481.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Greller, M. M., & Stroh, L. K. (2003). Extending work lives: Are current approaches tools or talismans? In G. A. Adams & T. A. Beehr (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, processes, and results (pp. 115–135). New York, NY: Springer.

Hasher, L., & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hershey, D. A., Jacobs-Lawson, J. M., McArdle, J. J., & Hamagami, F. (2007). Psychological foundations of financial planning for retirement. Journal of Adult Development, 14, 26–36.

Jackson, S. E., & Schuler, R. S. (1995). Understanding human resource management in the context of organizations and their environments. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 237–264.

Jex, S., Wang, M., & Zarubin, A. (2007). Aging and occupational health. In K. S. Shultz & G. A. Adams (Eds.), Aging and work in the 21st century (pp. 199–224). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jones, D. A., & McIntosh, B. R. (2010). Organizational and occupational commitment in relation to bridge employment and retirement intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 290–303.

Kanfer, R., & Ackerman, P. L. (2004). Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Academy of Management Review, 29, 440–458.

Kim, S., & Feldman, D. C. (2000). Working in retirement: The antecedents of bridge employment and its consequences for quality of life in retirement. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 1195–1210.

Kuvaas, B. (2008). An exploration of how the employee-organization relationship affects the linkage between perception of developmental human resource practices and employee outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 45, 1–25.

Lende, T. (2005). Older workers: Opportunity or challenge? Canadian Manager, 30, 20–30.

Li, J. T., Tsui, A. S., & Weldon, E. (2000). Management and organizations in the Chinese context. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Luchak, A. A., Pohler, D. M., & Gellatly, I. R. (2008) When do committed employees retire? The effects of organizational commitment on retirement plans under a definedbenefit pension plan. Human Resource Management, 47, 581–599.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. New York, NY: Wiley.

McArdle, A., Vasilaki, A., & Jackson, M. (2002). Exercise and skeletal muscle aging: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Aging Research Reviews, 1, 79–93.

Neal, M. B., & Hammer, L. B. (2007). Working couples caring for children and aging parents: Effects on work and well-being. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Ostroff, C., & Bowen, D. E. (2000). Moving HR to a higher level: Human resource practices and organizational effectiveness. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations (pp. 211–266). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ostroff, C., Shin, Y., & Feinberg, B. (2002). Skill acquisition and person-environment fit. In D. C. Feldman (Ed.), Work careers: A developmental perspective (pp. 63–90). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Park, D. C. (2000). The basic mechanisms accounting for age-related decline in cognitive function. In D. C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive aging: A primer (pp. 3–22). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Posthuma, R. A., & Campion, M. A. (2009). Age stereotypes in the workplace: Common stereotypes, moderators, and future research directions. Journal of Management, 35, 158–188.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714.

Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103, 403–428.

Shore, L. M., Coyle-Shapiro, J. A-M., Chen, X. P., & Tetrick, L. (2009). Social exchange in work settings: Content, process, and mixed models. Management and Organization Review, 5, 289–302.

Shore, L. M., & Shore, T. H. (1995). Perceived organizational support and organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano & K. M. Kacmar (Eds.), Organizational politics, justice, and support: Managing the social climate of the workplace (pp. 149–164). Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Shore, L. M., Tetrick, L. E., Lynch, P., & Barksdale, K. (2006). Social and economic exchange: Construct development and validation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 837–867.

Shore, L. M., Tetrick, L. E., Taylor, S. E., Coyle-Shapiro, J. A. M., Liden, R. C., McLean-Parks, J., … Van Dyne, L. (2004). The employee-organization relationship: A timely concept in a period of transition. In J. J. Martocchio (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 23, pp. 291–370). San Diego, CA: Elsevier.

Shuey, K. M. (2004). Worker preferences, spousal coordination, and participation in an employer-sponsored pension plan. Research on Aging, 26, 287–316.

Shultz, K. S. (2003). Bridge employment: Work after retirement. In G. A. Adams & T. A. Beehr (Eds.), Retirement: Reasons, processes, and results (pp. 215–241). New York, NY: Springer.

Shultz, K. S., & Wang, M. (2008). The changing nature of mid and late careers. In C. Wankel (Ed.), 21st century management: A reference handbook (Vol. 2, pp. 130–138). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Shultz, K., Wang, M., Crimmins, E., & Fisher, G. (2010). Age differences in the demand-control model of work stress: An examination of data from 15 European countries. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 29, 21–47.

Sowers, M. F. (2001). Epidemiology of risk factors for osteoarthritis: Systemic factors. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 13, 447–451.

Szinovacz, M. E., & Davey, A. (2005). Predictors of perceptions of involuntary retirement. The Gerontologist, 45, 36–47.

Takeuchi, R., Wang, M., Marinova, S. V., & Yao, X. (2009). Role of domain-specific facets of perceived organizational support during expatriation and implications for performance. Organizational Science, 20, 621–634.

Taylor, M. A., & Shore, L. F. (1995). Predictors of planned retirement age: An application of Beehr's model. Psychology and Aging, 10, 76–83.

Toossi, M. (2004). Labor force projections to 2012: The graying of the U.S. workforce. Monthly Labor Review, 127, 3–22.

Tsui, A. S., Pearce, J. L., Porter, L. W., & Tripoli, A. M. (1997). Alternative approaches to the employee-organization relationship: Does investment in employees pay off? Academy of Management Journal, 40, 1089–1121.

Tyers, R., & Shi, Q. (2007). Demographic change and policy responses: Implications for the global economy. World Economy, 1, 537–566.

Wang, M. (2007). Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: Examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees’ psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 455–474.

Wang, M., & Chen, Y. (2004). Age differences in the correction processes of context-induced biases: When correction succeeds. Psychology and Aging, 19, 536–540.

Wang, M., & Chen, Y. (2006). Age differences in attitude change: Influences of cognitive resources and motivation on responses to argument quantity. Psychology and Aging, 21, 581–589.

Wang, M., Henkens, K., & van Solinge, H. (2011). Retirement adjustment: A review of theoretical and empirical advancements. American Psychologist, 66, 204–213.

Wang, M., & Shultz, K. (2010). Employee retirement: A review and recommendations for future investigation. Journal of Management, 36, 172–206.

Wong, M., Gardner, E., Lang, W., & Coulon, L. (2008). Generational differences in personality and motivation: Do they exist and what are the implications for the workplace? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23, 878–890.

Wright, P. M., McMahan, G. C., & McWilliams, A. (1994). Human resources and sustained competitive advantage: A resource-based perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5, 301–326.

Zappala, S., Depolo, M., Fraccaroli, F., Guglielmi, D., & Sarchielli, G. (2008). Early retirement as withdrawal behavior: Postponing job retirement? Psychological influences on the preference for early or late retirement. Career Development International, 13, 150–167.

Zhan, Y., Wang, M., Liu, S., & Shultz, K. S. (2009). Bridge employment and retirees’ health: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14, 374–389.