In the morning, I awake with a monster-class Port Nolloth hangover.

“I wonder how the other guy feels,” I say to Jules, referring to Geoff Lorentz. She is lurking in the kitchen of our Bedrock Cottage, brewing very strong coffee. “Let’s go and have a look.”

With a serious case of the morning-afters, we crab-walk gingerly up to the Lorentz house. Mother Pam and the lusty Lara are in fine fettle.

“Oh, Geoff went out in the Blues Breaker (his tuppy) very early this morning,” is the astounding news. “The sea calmed down and conditions are perfect for work.” They give us tea in the courtyard. Pam, who should still be comatose after her birthday carousing, has just been leading an aerobics class for seniors. She is full of beans.

“Some time ago, the police conducted a huge IDB raid on the whole town,” she tells us. “The channel into Port Nolloth was closed. Geoff was at sea at the time and had run out of provisions. So I convinced the cops to fly out one of their helicopters, hover over the Blues Breaker and gently lower a pot of stew, a change of clothes and three bottles of Old Brown sherry in a net bag down to the boys.”

Whenever the Blues Breaker brought its gravel in to the TransHex plant, Lara became the sorter. For the rest, she raised their children, cooked hearty meals for the crew, waited for Geoff and worried when their boat was caught out in foul weather – just like the other Port Nolloth divers’ women. Lara and Geoff had been married for five years and adored each other.

“I sometimes grope him in the sorting plant,” she said, over a second cup of tea. “Geoff has to remind me of all the cameras in there, pointing at us. They must have some interesting footage by now.”

When a steamy little town like Port Nolloth lies between two obscenely rich diamond fields restricted by either the government or De Beers, it’s obvious that the inflow of illicit stones will make its way through its streets. It has always had the reputation for being the Casablanca of the Northern Cape.

Drugs were the new diamonds, we now heard. The night before, Geoff and Alfie had told us about the increase of hard drugs in Port Nolloth. Before, it was not unheard of for a diver to indulge in a marijuana joint or two. Alcohol, however, had traditionally been the escape substance of choice up here.

“Now we’ve got Nigerians in town, selling all kinds of drugs,” Geoff said. “And let me tell you, there are very few things more dangerous than a Mandrax-smoker diver.”

The divers went out in the tuppies maybe four days a month, when the Atlantic Ocean calmed down enough to let them in. Once out at sea and over a likely-looking section of gravel, the divers were faced with a daunting, very physical task. They descended in wetsuits deep into the Benguela Current, where it was dark, icy and uncertain. Once they reached the bottom of the sea, they shoved large steel nozzles into the gravel.

Things happened down there, in the undersea obstacle course of gullies, potholes and traps. Sometimes, huge rocks were dislodged in the ‘search-and-suck’ operation. In January 2006, 42-year-old Derrick du Plooy was pumping gravel in the sea off Alexander Bay when he was crushed to death by a huge rock that fell on him about 5 metres below the surface.

At sea, divers suffered injuries to joints, cracked ribs and burst eardrums from the rockfalls and decompression. On land, they faced boredom and booze. Now it was the drugs. And no one wanted to go out to sea with an addict, who could endanger everyone’s lives in so many ways.

As we left Port Nolloth, a ruby-red BMW roared past us (the driver had left the baffles at home) towards the jetty, its inscrutable smoky windows wound right up, with heavy hip-hop blaring out through disco speakers. Was this a Nigerian drug dealer, or just another crazy Namaqualander letting off steam?

Our destination that day was De Beers’s Kleinsee, part of the world diamond industry, a business that extracts 120 million carats of rough diamonds from the planet annually. Just more than 20 tonnes of diamonds are sold to producers for US$7 billion. Once they are cut, set and ready to appear in a Manhattan jeweller’s window, they are priced at US$50 billion. Really good business for a generally useless little piece of carbon.

The amiable De Beers public affairs manager, Gert Klopper, arrived at the gates of Kleinsee to help us through Security. Suddenly, from the rowdy roughand-tumble of Port Nolloth, we were in a neat, box-like, litter-free town where people kept to the speed limit. There was not a Nigerian drug dealer in sight.

On the mine tour, we heard that De Beers was rehabilitating its disturbed areas.

“In 50 years’ time, people won’t even know there was a mine here,” we were assured.

Back in the late 1920s, while diamond fever was sweeping the northern reaches of the West Coast, a teacher called Pieter de Villiers was on another mission. He was building a farm school near the mouth of the Buffels River at a place called Kleinsee. One day, by chance, he kicked a diamond out from the ground.

And so Kleinsee Mine was born, with Jack Carstens as the pit manager. He tells of the nights when ‘the crooks’ would arrive at the diggings to steal the diamond gravel from under their noses. His Namaqualander guards carried electric torches, their ‘wizard devices’. The guards thought you could immobilise a man if you shone your torch on him.

In A Fortune Through My Fingers he relates a conversation he once had with a guard called Jan. Jan tells Jack about some ‘crooks’ he had found in the section called the Main Area:

“I torched them and they didn’t fall over so I went quite close to them and then they ran away and I couldn’t catch them.”

Other crooks who escaped with Kleinsee diamonds had it easier. They didn’t have to endure any form of the quaint ‘Namaqua Torchlight’ torture. In July 1932, a consignment of 10 000 diamonds worth about £53 000 was nicked from the Bitterfontein post office on the way to Kimberley.

Dressed like dude miners, we climbed into a bus and drove past the faceless, windowless, final-processing plant, where no human skin touched a diamond. It was all done with conveyor belts and quarantine gloves under the constantly watchful eyes of many cameras. Not a touchy-feely kind of process.

Further along, we came to the bedrock, where the diamonds were. Massive suction units were being used to hoover up the gravel. Our guide, Mariska Theunissen, said the workers here were encouraged not to bend down.

“And if they do, it’s considered very good manners to immediately hold up their hands to show what they’ve picked up.”

We came to the main event of Kleinsee: the dragline, a monster machine that loomed above the skyline and needed its own transformer station to power it.

“Every Sunday, when they start it up, the lights all over the town of Kleinsee go dim,” said Mariska. The dragline saved a lot of spadework – its 36-tonne bucket could eat 72 tonnes of soil with every bite. Every year, it was stripped down and serviced from top to bottom by 150 technicians.

As we toured the massive mining area, we learnt more about working and living in Kleinsee. For one thing, there were no speed freaks on the diggings.

“Every driver has a magnetic ID device that he must use whenever starting a vehicle,” said Mariska. “This monitors how long he idles, how fast he drives, how much the engine is revved and whether he’s hard on the brakes.”

Back at the Welcome Centre, we asked Gert about Kleinsee’s water source. Most of it came from the Gariep River, he said. But they also took water from the nearby Buffels River, which was notoriously brackish.

“Let’s just call it water with attitude,” smiled Gert.

“People get used to the brackish taste,” added Jackie Engelbrecht, his colleague. “When they leave Kleinsee, some of the older people like to add a pinch of salt to their coffee because they’re so used to the mineral taste of the water.”

We saw the museum, founded only after a local farmer had shot a leopard. He had it stuffed and then discovered there was no place to display it. So the raccoon-eyed leopard now stood stiffly next to a diorama of brown hyena and a collection of startled stuffed birds.

Jules and I drove over to the Houthoop Guest House, about 15 km out of Kleinsee. While we were unpacking the bakkie, a large group of German bikers arrived in a cloud of dust and bonhomie. They stripped off their leathers and settled themselves in sunlight, knocking back beer after beer. It turned out they were a swashbuckling gang of gay dentists and doctors from various parts of Germany. Every year the Dauntless Docs took themselves off on motorbikes to some exotic part of the world.

The grounds of Houthoop were festooned with homespun homilies in the form of dozens of signs. In the course of five minutes, I learnt that:

• “A bargain is something you can’t use at a price you can’t resist”

• “Whenever I feel blue, I start breathing again”

• “Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take, but by the moments that take our breath away”

• “Never, under any circumstances, take a sleeping pill and a laxative on the same night”

Veronica van Dyk, the owner-manager of Houthoop was, we discovered, the compiler of the wisdoms. For dinner, this incredible woman gave us steaks, salads, rosemary potatoes, pumpkin fritters and all the garlic prawns we could eat.

The next morning, it smelled like France wherever we went. Floors Brand was on hand to guide us on a great field trip through the De Beers estate – a trip that, thankfully, would at last have nothing to do with a diamond. This was day eight of our Shorelines adventure, and almost every single waking moment had been about diamonds. And they’re not really forever. I read somewhere that if you dropped them at just the right angle onto a hard floor, they could shatter. But enough, already, about diamonds.

“Sorry about the garlic,” Jules told Floors.

“Don’t worry,” he assured us. “I had garlic all over my mashed potatoes last night.” Bonjour, then.

The tall, grey-haired Floors was the retired estate manager for Kleinsee. Only 12% of the 400 000 hectares owned by De Beers in these parts was under mining. The rest of it was dunes, shipwreck coast, succulent gardens, seaside hideaways, secret smuggling bays, old legends, mystery stories and, at this time of the year, hundreds of bonking tortoises who had suddenly discovered a dash of speed. Like I said, no diamonds. Thank you, Lord.

We parked at the wreck of the Border, which went down in dense fog at high tide on 1 April 1947. All that was left of this cargo ship was a rusty hull on the beach. But the weather was stormy and grey that morning – with the West Coast at its least forgiving. The perfect atmosphere for a shipwreck tour. I photographed a hardy Mesembryanthemum crystallinum (its English name was lost to me) battling through the layers of thick rust on the deck of the Border. Life escaping out of the dead.

I heard crunching and swung about in alarm, one of my Canon cameras nearly taking my nose off. It was the good wife, who had discovered the joys of jumping on a bed of dry, black mussel shells in her hiking boots. Like a little girl who has found a large sheet of plastic wrapping paper that pops. Floors, bless his soul, didn’t bat an eyelid. Knowing we’d had one mine tour too many, he just let us play with our rust-bed succulents and dance on our crunchy mussel beds.

We drove on and stopped at one of the many bays, where drifts of plovers ran up and down at the edge of the wild, breaking waves. Scouring winds drove the warmer surface water away so that the icy water deeper down was forced upwards, carrying plankton and nutrients with it.

“This is the Benguela Current, what they call The Upwelling,” said Floors. “This is what makes the waters off the West Coast so rich.” This, obviously, was why so many seals regarded the area as prime coastal property.

We continued and found a Strandloper midden where the ‘old people’ used to quaff piles of limpets. Floors showed us how to tell the difference between ‘natural death’ limpets and ones that had been hammered open by hungry protohumans.

On the way back to the vehicle, he called us over to observe the difference between Gazania lichtensteinii and Gazania meyerii (one leaf is slightly larger than the other).

“The best way to appreciate Namaqualand is on your knees,” said Floors.

We found the wreck of the Arosa (it went down on 16 June 1976, which was also the day Soweto erupted and the freedom fight for South Africa officially began). It was a concrete-carrying vessel that was allegedly run aground on purpose. Then Floors showed us a wreck that carried the rather Disney-esque name of Piratiny, a 5 000-tonne Brazilian steamer that floundered off these shores in June 1943, possibly sunk by a German torpedo.

Weeks after the shipwreck, a heavy storm blew up, leaving the beaches covered with luggage from (and pieces of) the Piratiny, which included quantities of dress materials and bolts of silk. Several months later, at the church-communion service, all the local children came uniformly dressed in clothes made from the Piratiny flotsam.

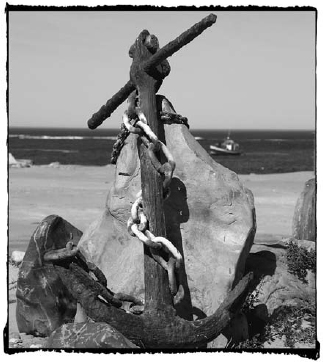

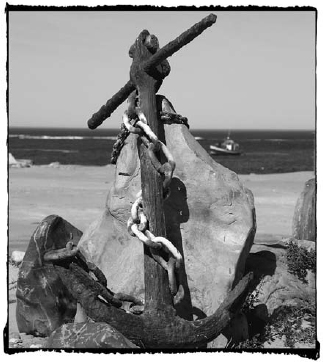

We found Noup, a tucked-away cove where diamond divers used to hole up in a collection of eccentric, weather-beaten cottages – all facing the noisy sea.

“I’ve slept here from time to time,” said Floors. “It feels like the ocean is just waiting to burst in through the front door.”

Driving through the De Beers game farm, we encountered a number of very preoccupied male angulate tortoises intent on crossing the road at high speed in search of willing womenfolk from their tribe. Normally when one shoves a wide-angle lens into a tortoise’s face, he withdraws into his shell. Not these fellows. They glared up at me like movie stars dealing with paparazzi: if you value your big toe, you’ll get out of my way …

Floors was concerned with questions of land ownership in the area and with making sure that the sandveld had every chance of recovery and survival. He was acutely aware that De Beers was unpopular in the region. Many local farmers suspected the company of acquiring land here in the past in underhand ways. Floors had also been De Beers’s man in negotiations to hand over the area between the Groen and the Spoeg rivers to the National Parks organisation to be part of one massive conservation district.

It was a day of miracle and wonder with the grizzled, amiable Floors, whom we’d come to like a lot. He also showed us that the oft-maligned De Beers (and there are many reasons to take issue with this diamond giant) had, ironically, kept a huge section of the South African coastline pristine and free (for the time being) of developers and their grubby little millionaire condo-plots.

Time spent in the company of Floors was also a window into the soul of the true Namaqualander. Like the hardy succulents of his region, Namaqualand Man is minimalist, stripped down by the elements of his environment, living by his own rules.

His is not a world of duvets, wide-screen TV sets or sushi bars. Just give him a karos (buckskin blanket), a sad old song and a plate of stormjaers – little doughball dumplings rolled and fried in fat.

That night, the threat of stomach bombs was far from our minds. Our hostess gave us chicken tortillas – and some parting words of wisdom:

“Most of us go to the grave with the music still inside us.”