Autumn, 1997. The West Coast hamlet of Elands Bay wakes up to a foul-smelling invasion from the sea. It is D-Day for the West Coast rock lobster (some fools like me mistakenly call it crayfish) and thousands of them emerge from the depths, gasping in a crustaceous manner. For a local fisherman, who is legally allowed four tails a day, it’s a sin to see 2 000 tonnes of young and tender lobster arrive in this pathetic fashion. For the seafood-craving tourist who pays hundreds of rands to land one on his dinner plate, it’s equally shocking. Instead of temperamental chefs preparing the delicious tail, boiling and garnishing it and then presenting it with a flourish, massive front-end loaders are hauling piles of dying lobsters away to be dumped.

In the summer of 2002, about 1 200 tonnes of lobster come marching out at Elands Bay again, demanding oxygen. This time environmental officers, policemen, the army and the navy are called in. Even members of the public pitch in where they can. They save a hundred tonnes of lobster, rushing them to commercial holding tanks or flying them by helicopter out to more aerated parts of the sea before they die of exposure.

And back in the cities, we stare at the newspaper photographs of kreef piled up on the beaches. Our mouths water, and we find ourselves reaching for the mayonnaise sauce. Is it safe to eat a ‘walkout lobster’? Sometimes. And then sometimes not. Not good odds for the seafood lover.

What causes this mass walkout? Ironically enough, it all comes back to the upwelling, that glorious wind-driven process that forces nutrient-rich cold water up from the depths. It’s feeding-frenzy time for marine life and everyone along the food chain has a party. But as the upwelling matures, sometimes diatom blooms are born. They literally consume all the oxygen in the water as they decay, leaving the local sea life very short of breath.

If you go for a cyber walk through Internet World, somewhere near the corner of Loopy Canal and Crazy Street, you’ll find a whole bunch of sites that will tell you the ‘Red Tide’ comes from other quarters:

“And the second angel poured out his vial upon the sea; and it became as the blood of a dead man: and every living soul died in the sea.” – Revelation 16:3.

The end is nigh. Prepare for your doom. That kind of stuff.

We were sitting down for supper at The Cabin Restaurant back in Doring Bay, discussing lobster matters. Owner Elize van Wyk was doing something magic with a kabeljou in the kitchen. Even though it was her husband Reynold’s 67th birthday, he was happy to join us and talk about West Coast life. Lobster, in particular. Kreef.

Outside, a kick-ass storm was lashing the West Coast like a fishwife beating a straying husband. Furious, wind-driven rain bulleted onto the windows. At sea, the whitecaps came galloping onto the beach. I shuddered with pure delight to be here, out of the storm. With something fishy happening in the kitchen and something cold to hand.

Reynold told us the story of the old canning factory down by the lighthouse.

“In the 1930s the North Bay Fishery Company set up its operations at Doring Bay,” he said. “To secure the land, they paid a certain Mr Bleeker to moor his canoe out in the middle of the bay and stay there for six months so that permanent residence could be claimed. They set up a corrugatediron-roofed factory and built about 20 houses for their workers – wood panelling inside, corrugated iron outside.

“Not one of these homes has been demolished. In some of them, however, the corrugated iron has completely rusted away and been replaced by brick. But mostly, the wood panelling inside has been retained.”

In those days, only poor folk ate rock lobster. The middle classes used them as bait. Ironically enough, the French were paying local fishing companies top franc for good tail. That’s probably why, to this day, the prices are still too rich for local tastes, and most lobster caught in South Africa is exported.

“We used to take them out from under the rocks, twist the tails off and use that for bait to catch hotnotsvis,” said Reynold. Then he leant over the table towards us, lowered his tone and added, in a conspiratorial whisper:

“But I, for one, have always loved eating kreef.” It sounded like dining on lobster was something you did privately back then, so the neighbours would not think you were ‘broke and eating bait’.

The Van Wyks arrived here from Lambert’s Bay in the mid-1950s. It was a time of plenty for the lobster industry. Everyone had a job.

“In fact, they brought in 500 Xhosas from the Transkei to help catch the kreef,” said Reynold. And then the resources were completely overfished in the quest for larger dividends for shareholders. And, of course, bigger bonuses for management types. Soon there were very few little tails wagging out from under the rocks. There was no work. But most of the 500 Transkeians stayed on in the hope of something happening.

In the 1980s, with the lobster industry on the rack, young people began filtering out of Doring Bay in search of a life somewhere else. Houses emptied and a stillness settled on the little cove again.

“We lost people and buying power,” said Reynold. “Things became petty. I once sold baby food to a coloured mother after one o’clock on a Saturday afternoon and another shop reported me to the authorities. I received a stern warning from the magistrate. This small-town mentality …”

I was in too good a mood to climb further down the wormhole of lobster-town politics that evening, so I enquired after some West Coast biltong: the famous bokkoms. Reynold immediately brightened.

“Here,” he said, flourishing a bag of the stuff. “I’ve got a guy who vacuum-packs it for me.”

I have to say my first encounter with bokkoms was not as bad as the time I had to drink deer-foetus whisky in a Borneo bar with a bunch of oil workers, back in my bold and silly youth. But it wasn’t a highlight, either. It was tough and smelly and bony and not very nice at all.

There were still two chunks of this ominous, dark fish flesh in the packet. Jules and I sneaked a look at one another. What to do with the smelly stuff? We could definitely not use the bokkoms as car deodoriser. We could also not eat another piece. But nor could we just leave it there on the bar counter. Reynold would be deeply hurt. So we carried the bag of stinky fish with us to the dinner table, where the delightful Elize brought us firm-fleshed, fresh kabeljou and veggies. The bag of bokkoms lay reproachfully near the salt cellar. And was conveniently forgotten when we left the restaurant.

Walking out, I felt the hairs on the back of my neck tingling. I half-expected Reynold to come running up, saying:

“Guys, you forgot your bokkoms …”

The next day we left Doring Bay (after startling the Van Wyks by giving them each a warm, Jo’burg farewell hug) and headed off inland for another ‘tree house moment’. Let me explain. It’s when you develop an obsession with something obscure. An experience you want to capture and take back to your tree house and look at and polish when days are dark – and friends aren’t answering the phone.

So it was with the Heerenlogement, a seemingly obscure cave on the Trawal road about five rooibos tea farms from Doring Bay. This was the Holiday Inn of the 1700s. The Benbow Arms of the 1800s. A stopover for adventurers, crooks and prospectors. It had a freshwater spring and grazing on the hill slopes. It could be guarded. From the mouth of the Heerenlogement you could see forever.

The famous Oloff Bergh passed through here in 1682 on his way to the north in his search for copper fields. It must be noted that Oloff’s trusty guides (I don’t know if they were Bushmen, Strandlopers or Khoi) actually showed him the cave. Most Africa explorers of old had to be led to the sites they eventually discovered – a fact that carries its own strange irony.

Just more than a century later, the Heerenlogement hosted its most flamboyant guest, in the form of naturalist (hunter, endearing character, ‘soft touch’, baboon-lover, general show-off and possible philanderer) François le Vaillant. The Frenchman arrived in splendour, ostrich feather in his wide-brimmed hat, the scheming Chacma baboon Kees at his side and a retinue of Khoi and their wagons in his wake.

They stayed there for a week, eating dassies until they could take it no more. François le Vaillant’s name was scratched on the inside wall of the cave, along with others like Bergh and Andrew Geddes Bain. For my money, it’s the most significant, mysteriously misspelt graffiti in South Africa.

Lunchtime at Lambert’s Bay, and we trooped out to Bird Island to watch the gannets in their multitudes. Nearly 25 000 of these ‘mad geese’ were going through the entire gamut of gannet protocol: sky-pointing, bowing, preening, feather-nibbling, hovering and squawking as they landed and took off. Who wants to be a gannet air controller?

There’s an old West Coast yarn about the local form of capital punishment, back in the days of the guano hunters. You strapped a fish to the condemned man’s forehead and floated him out to sea, where a dim-witted diving gannet would gouge his brains out with his beak. We also heard (and this was, quite possibly, a true story) of a guy who drove his inflatable dinghy through a flock of rising gannets and was speared through the neck.

Several weeks after our October 2005 visit, the endangered gannets at Lambert’s Bay deserted Bird Island en masse. Conservationists confirmed that the exodus was provoked by seals attacking nesting birds at night. About 300 breeding gannets were killed within a few weeks. Seals had been reported attacking the birds at sea off the island. Studies show that up to 10 000 gannets may have died through seal predation between 1998 and 2002. But the seals had never attacked the (estimated) 11 000 pairs of nesting birds on shore, despite the presence of a growing seal colony on the island since 1985. An entire gannet-breeding season at Bird Island was lost, with gulls eating up the abandoned eggs. Bird Island gannets make up 14% of the world’s gannet population. The Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism has since issued permits to shoot seals – mostly adolescent males – that attack the seabirds.

But the tales of the guano collectors on this vast coastline were the most gripping. At one stage, more than 500 competing guano boats were moored off Ichaboe Island, further north, off Namibia. A typical squabble between guano hunters would begin with someone tossing a rotten penguin egg at someone else. Then a live penguin would be hurled in anger. Then out would come the cutlasses and pistols. Artificial fertiliser arrived in the 1960s and the bottom fell out of the guano market. So to speak. And all the crazy men left the island.

After visiting the gannets, we returned to the mainland, fell on a lunch of fish and chips like wolves (those wolves, obviously, who eat fish and chips) and remembered a previous visit to this place, when the air was thick with the stench of fish being processed. We mentioned this distinctive aroma to restaurateur Isabel Burger, whose husband worked at the fish factory.

“That smell? That’s the smell of our money.”

The real smell of money around here lay in the ‘chips’ side of the fish-and-chips business. There were more potato farmers up here in the sandveld than you could shake a dipstick at. Those very farmers were having a potato convention in Elands Bay when we chugged into town and took up temporary lodgings at Die Bottergat (The Butter-bum).

“Pin a tail on me, call me a weasel,” Jules kept chanting (this, for those who don’t know, is her ‘I’m Very Impressed’ song) as she moved through the charming little traditional cottage. She raved over the succulent garden outside, the massive hearth inside, the quaint family photographs on the walls, the bottles of Voortrekker Inflammation Oil and Cape Dutch Chest Drops, the paraffin storm lanterns and the yellowwood cabinets. From the rafters hung bunches of dried flowers and tumbleweeds and mobiles and decorations made from sea-urchin shells and bits of motherof-pearl. We could picture happy families here, on rainy days, working away at these mobiles.

But why the name, we asked the caretaker, Hentie van Heerden.

“A Mr Van der Westhuizen bought the plot in the old days for next to nothing and built this cottage,” he said. “When his children inherited it, the place was worth a small fortune. They said they had landed ‘with our bums in the butter’. Hence the name.”

The waves at Elands Bay, Hentie said, did more than occasionally cough out tonnes of lobster.

“It’s a great surfing spot. The waves form a left-hand tube that spits you out in the general direction of Lambert’s Bay.” A left-hand tube? Mmm. As opposed to a right-hand pipe? The wondrous world of surf-speak still lay before us like a foreign country.

“How about some snoek, then?” suggested Jules, and off we went to the Elands Bay Hotel. On the porch, two ravenous surfers stood devouring large quantities of sandwiches, chips and coffee, gazing intently out at the waves. That left-hand tube thing again.

The snoek was fresh and firm and very tasty. It has always been my favourite fish, mainly because it has big bones that you can see and extract right away. None of that Sneaky-Pete, barely visible, skinny-bone shit that sticks in your craw and makes you search your own gullet with a mirror and tweezers in the dead of night. Snoek is honest eating. I like snoek.

We had questions for Celeste Kriel at Reception. Firstly, what happened to the tail of the fat hotel dog? Secondly, had she ever seen a snoek run?

“That’s Kisha. We’ve tried to put her on a diet but it doesn’t work. Her tail was bitten off in a fight, back in the days when she still could move around.

“I’ve seen a snoek run, believe me. In August the snoek ran for the first time in many years. You could not believe the excitement. I just had to drop everything and run to the beach and watch. The fishermen were hauling in snoek after snoek, singing and laughing as they worked. It brought tears to my eyes.”

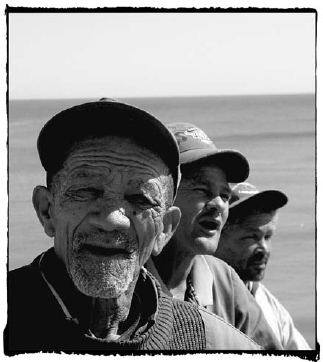

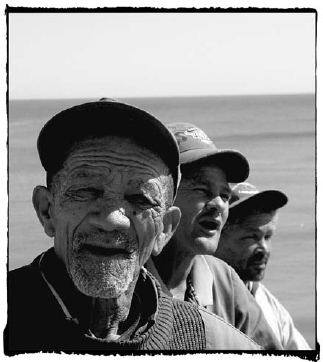

We promised Celeste we’d return that evening for drinks at the bar. Heading out to Leipoldtville for the afternoon, Jules and I came across a couple of Xhosa fishermen and their slim pickings of hotnotsvis. Simon Mxeba and Themba Metu had come here more than 30 years before from the Transkei to fish – and simply stayed. They were far from home. Hentie told us earlier that when the Xhosa workers were first shipped over to the West Coast to begin their new careers as fishermen, they were taught to row the little skiffs in Verloren Vlei. Over the years, they became expert fishermen, plying the Atlantic shoreline off Elands Bay like salty sea dogs.

“For better or for worse, this is now our home,” they said. The West Coast had crept into their souls.

We continued past swathes of potato farms eating up the sandveld (and not in a nice way) into the quiet village of Leipoldtville, named for the father of C Louis Leipoldt, the legendary man of letters. And of cooking, as my travel mentor, the late Lawrence Green, writes. In On Wings of Fire, he says Leipoldt liked to eat hippo meat, dikkop stuffed with orange, breast of flamingo, lizard, squirrel, hedgehog, giraffe tongue and pickled swallow. Regular ‘critter cuisine’. I wonder what he would have thought of Reynold van Wyk’s bokkoms back at the bar in Doring Bay?