August 1997, the French Quarter, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. Hurricane Season in The Big Easy. It has been a night to remember. Early dinner on the balcony of the Café Royal (corner of St Peter and Royal): for me it’s Creole Barbecued Duck, served with red-pepper jelly and smoked-sausage jambalaya. Here, check out the menu. Might I suggest the Creole File Gumbo with red beans?

Down to the clubs on Bourbon (locals just call it ‘The Street’) for a little Zydeco swamp music, some blues and a peepshow along the way: “Topless! Bottomless! See ’em as God made ’em, folks!” yells the sidewalk barker outside Big Daddy’s Bar. A drive out to the legendary Tipitina’s to see the Neville Brothers singing those sweet Louisiana jailbird songs of our youth. One for the road back in the Quarter at the Old Absinthe House Bar where the ever-lovely, smiling Sunshine Corrigan dishes out late-night daiquiris, cigars and advice to the lonely and the lovelorn.

And now we’re chatting quietly in the enclosed garden of the Audubon Cottages in Dauphin Street among the banana trees. Soft rain is sifting down through the leaves, the jovial madness of the French Quarter is but a murmur beyond these walls as we sit, my friends and I, at peace with the world.

Eight long years later, I sensed the same wild street magic as I looked down from the balcony of a crazy backpacker establishment in Long Street, Cape Town. Could this be Bourbon Street Extension?

We blew into Cape Town from the West Coast on Monday 10 October (World Egg Day), feeling a little ragged around the edges. Sixteen intense days on the road and here we were at a BP Express filling-station convenience store outside Bloubergstrand, clutching Wild Bean cappuccinos, blueberry muffins and biscotti in celebration. The staff behind the counter were so chatty we thought they’d swallowed Ecstasy tablets for breakfast.

“Welcome to Cape Town,” our counter lady said. “And you must visit [insert forgettable name of venue here], they’ve got Real Animals! Lions! Cheetahs! And you can pat them, too!”

We blinked in alarm. Thanks, we will.

Caffeine drip in place, we drove into the City Bowl, causing at least 10 traffic incidents that would have occasioned major road rage back home in Johannesburg. The Capetonians were calm and forgiving. They didn’t lift that middle finger. No rotten penguin egg was tossed in anger.

We found our way to 255 Long Street, to an upstairs affair called Carnival Court. I had booked us into this establishment to get the feel of backpacker travel and of the legendary magic mile in general. At the top of a nearly vertical flight of stairs sat young Ntombi, who told us where to park our bakkie safely away from the little prying fingers of the street children.

Out on the street, we met the guardian of the block. The soft-spoken, lean Shamiel (Sam) Samson was a former Navy man and he looked the part.

“Welcome to my place,” he said earnestly. “There is no crime on my block. I sort things out myself.”

What about the infamous street children, we wanted to know.

“They’re like my kids,” he said. “And I see all the people on the street as my customers.”

Reassured, we commenced to drag our luggage up the stairs to our room. On the way, a young German backpacker mistook me for the manager and asked me some questions I couldn’t answer. Room No. 3 looked out over an alley, a barbed-wire rooftop (an anti-street-kid measure) and a slice of Long Street. The clean room was equipped with basic bed, desk, chair and cupboard. We lay back on the bed and observed the evocative shapes of the stains on the walls. I could see Antarctica and Greenland. Jules found Tristan de Cunha and the Azores.

“And if I close my left eye and turn my head slightly … there! I can see some of the Philippines,” she added. I hauled her up off the bed to go exploring the caverns of Carnival Court.

On our floor there was a foosball table, a multilingual library of tattered backpacker literature (take one, leave one), the Zanzi Bar, where tattooed youngsters played pool beside an old fireplace, and photographs of street children on the walls everywhere. The best feature of Carnival Court, the spot that took me right back to the Café Royal in New Orleans, was the filigreed metal balcony, which ran almost the full length of the block. From here, in good company and with something cold to hand, you could view Long Street in all its colour and intensity.

Charl Henning, the young night manager, was the guy who allowed us into Carnival Court. They did not usually take bookings from South Africans, but because of our writing mission they let us stay.

“This place used to be a bordello,” he said. “Our first backpacker customers four years ago were Japanese hippies who were into trance and pot. Then there was a Malaysian who slipped sleeping potions into everyone’s drinks and rifled through their rooms while they lay passed out. But there’s not much of a crusty element at Carnival Court any more, although some people still come in and try to book a room by the hour.”

Hookers and hustlers. That was the reputation of Long Street for as long as I can remember. I used to come play here in the clubs back in the 1980s, when the street was dark and dodgy and you rubbed shoulders with sailors and prostitutes.

“That’s changed,” said Charl. “Backpackers, bookshops and breakfast places have arrived.”

Angela Church, an attractive 22-year-old serving drinks at the Zanzi Bar, was a bit of a Sunshine Corrigan – a neighbourhood connoisseur.

“Long Street is a wild card,” she said. “All kinds of people walk down this street. I often see a guy who dresses up in 17th-century clothes, complete with ruffled shirt and velvet coat. There’s another fellow who comes around here who is amazingly well read but is homeless.”

Angela, a student of media, literature and film at the University of Cape Town, was doing a special study on street people.

“Humans are human because of their interaction with other people,” she said. “But street people are not seen in that context.”

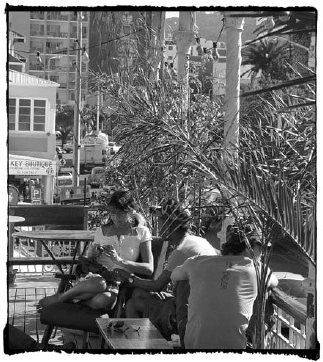

I went out onto the balcony of the Zanzi Bar with my beer and sat down. Jules strolled out to join me and we began talking about our Shorelines trip. Were we really going to make it all the way around the coast of South Africa? More than eight weeks of wandering still awaited us.

“Me, I could just park here for months on end,” I said. We sat and eavesdropped on Long Street in the late afternoon. The peak-hour traffic flowed uphill, the packs of skateboarders weaved their way downhill and the aroma of a small dagga cigarette wafted up to us.

“Look!” Jules urged, pointing at the street below.

He was unmistakably Maasai. Tall, impossibly thin, like a long-legged heron, braided hair, shukka over the shoulders, fly whisk and milk gourd to hand, thousand-miler sandals on narrow feet. He came loping through the traffic on Long Street, eating up the road with Serengeti strides.

I flew down the stairs of the Carnival Court with my camera and found him shopping at the Long Street Superette. He clutched a loaf of bread and a bottle of milk under his arm and stood at the counter waiting his turn, on one leg.

“Jambo!” I said, unleashing my entire Swahili vocabulary in one breath.

“Habari!” he replied automatically, looking down at me with a smile. And then we switched to sign language.

“Hello strong man,” said a guy from the Democratic Republic of Congo to the Maasai warrior. “Have a banana.” And then I simply somehow lost my Maasai.

I went outside and found Sam Samson.

“If you see that guy in the red tablecloth again, please come and tell me.” He said he would.

We later found out the Warrior of Long Street was Miyere Miyandazi, who had walked all the way from a village near Lake Naivasha in Kenya to Cape Town to protest against human-rights abuses against his tribe and the erosion of the Maasai culture in general.

Everyone in Cape Town seemed to know a little something about Miyere. He’d been spotted in the city and all around the Peninsula. He caused a special sensation down in Kalk Bay outside the Olympia Café, where the bicycle yuppies gather for baguettes and designer coffee. Miyere had stood on one leg for hours (it seemed like days to the customers) outside the café, simply staring in through the plate-glass window.

“And there’s a cow he visits regularly,” said Angela Church from behind the counter at the Zanzi Bar. “It’s somewhere up on Signal Hill.”

By the time our dinner guests arrived, I was in a joyous froth about Long Street. We had a leisurely curry supper across the road at Maharajah’s and ended the night with a party at the Long Street Bar, just below Carnival Court. The next morning, I telephoned one of our group, journalist Geoff Dalglish, to wake him up for his early-bird flight up to Jo’burg. How was he feeling?

“You’ll be hearing from my lawyers,” was his throaty reply. OK. So it had been a good party, then.

We had breakfast at a place called Lola’s, where a young girl sat in the far corner, sobbing gently into her pashmina. We went on a bookshop safari that took in eight great establishments on Long Street. Jules and I had to make constant stops at Room No. 3 to offload our new second-hand (I haven’t got my tongue around ‘pre-loved’ yet) purchases, and one could sense that the book vendors of Long Street were happy.

One of the shops was Clarke’s Books, an ancient establishment that had a creaky upstairs room lined floor to ceiling with the written word. I was instantly transported back to the village of Hay-on-Wye in Wales, the centre of the second-hand book universe.

We fell in with Cathy from Serendipity Bookshoppe, where I bought Tintin in Tibet for Jules, who unashamedly gave me a rather pleasant French kiss in front of everybody on Long Street. Right then, I felt the spirit of New Orleans rise up in my soul, and I thanked God for the fine wife he’d sent me.

I was so taken by the sensational snog that I left my credit card on Cathy’s desk.

Down a crooked alley of antique shops we found a place called Proseworthy and almost broke out the champagne on the spot. Nestled in amongst other works was a book for which we’d been hunting for more than a decade: Eugene Marais’s Road to the Waterberg and other Essays.

I wanted to pay but my credit card was absent.

“Ah, you’re the man they’re all looking for,” said Proseworthy’s Joanne. “Cathy from Serendipity has been calling all the way down the street after you. Your card’s with her.”

We continued to the Long Street Book Shop, where David Smith said:

“Ah. The Long Street tom-toms have been a-beating. I know about you and your card.”

“Yes,” I replied. “There’s a certain Jopie Kotze at a certain Springbok Lodge up north who also knows the card.” I bought Peter Fleming’s News from Tartary from David.

At Select Books, near our reach of Long Street, we met David McLennan, also known as ‘Mr Book Man’ by the street children.

“They know everything about this street,” he said. “A few months ago we had a problem with the plumbing at the back. We needed a long pipe to clear the blockage but had no idea where to get one quickly. I asked the street kids for help and within minutes they were back with the perfect tool.”

Within two days the book dealers of Long Street had become friends. They started giving us some of their books and magazines for free. It felt like we’d stumbled into a village in the middle of a big city.

We lunched at the Café Mozart in Church Street near Greenmarket Square, where waiters in red aprons bustled in and out of the kitchen with concoctions of food so beautiful that it seemed an awful shame to eat them. I had smoked-springbok salad with avocado and feta cheese. Jules had a Moroccan dish of poultry and roast vegetables and then we went off to shop for loud shirts and funky necklaces in this street that sounded just like a husky Tom Waits song.

There were Gabonese masks (try one on while they plait your hair into braids), World War I gas masks (Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori – I think not), hippo teeth, stuffed voles, ships in bottles and a special on trumpets, there was a session at the Turkish Baths, an old-school haircut executed by Carmine at the candy-striped barber shop, carved doors from Mali, a shop called White Trash, hot snoek and slap chips, another chocolate expresso and then we found ourselves in the company of our friend the writer Pat Hopkins, drink in hand, back at the Long Street Bar. Hopkins was nearly robbed of all his possessions by the street kids on the way back to his digs on Greenmarket Square in the early hours. But he turned on them like an angry badger, so they wisely slunk back into the shadows.

The next morning, Jules and I did a dawn patrol past the sherbet-coloured homes of the Bo-Kaap as the suburb was waking up and packing kids off to school for the day. Bergies (street people) sat nursing their heads on the pavement, offering us some of their Cape Calypso Late Harvest for R10 a sip. Further along the road, a Palestinian flag snapped in the early-morning breeze, and the owner of the house said:

“We’ve got guests from the Gaza Strip.” And went back inside to chivvy her children along. I was starved and said so. We both agreed on greasy samoosas for breakfast. The man at the Biesmiellah Café said to wait 20 minutes and then he’d feed us the best samoosas in town. They were truly worth the wait.

At the Rose Corner Café the lady behind the counter sold us a Muslim cookbook called Boeka Treats (snacks to break the Ramadan fast with) and we returned to Long Street for more breakfast of the pepper-steak variety at the Halaal Pie Corner.

We darted past St George’s Cathedral to visit the flower sellers of Adderley Street. Jean Solomons, who had been flogging flowers here for 40 years in the family tradition, said she sold roses to “naughty men” on Fridays.

“On Mondays, I sell to the women, who like to take flowers to work.”

Scant metres from Carnival Court was Adult World on Long Street. Jules had never been to a porn shop in her life. We entered a universe where terms such as ‘cramming for the big one’, ‘sweet bullet of passion’ and ‘polar hump’ had their own special meanings.

“Some of our best clients are rugby players who like to dress each other up in frilly maids’ uniforms,” said the lady behind the counter, shocking me to the core. From the Currie Cup to the ‘C’ Cup. We walked out, just in time to see a laundry van come barrelling down Long Street bearing the slogan:

“Everyone has dirty laundry …”