As a Cape fisherman, nothing really surprises Achmat Hendricks out on the inky waters of False Bay. But he’ll never forget the day ‘the Japanese’ came to sea with him.

“The first catch of the day is a little steentjie. One of the Japanese women on board takes a knife out of her bag and stabs it near the gills. I’ve never seen anyone kill a fish so fast. They don’t even take the scales off. They just fleck it open and start eating it raw.”

Achmat steers his boat out into open waters, his jaw having dropped at the sight of the ravenous guests falling like wolves on the fish. Didn’t they have enough breakfast? He realises this is no sight-seeing tour of the legendary place where the Atlantic and Indian oceans butt waves, with a little fishing demonstration thrown in for fun. This is an alfresco instant-sushi experience. These guys want to eat from the seas today – and by their ‘lean and hungry’ look, they plan on dining on both oceans.

“Then I catch an octopus. If you know your octopus, you’ll know it doesn’t die quick. I usually turn it inside out and it can sometimes take a whole day to die. This woman, this same woman, just bites it around the eye and it dies immediately. And then they eat it.”

Jules and I had come down to the Kalk Bay harbour on this, the twentieth day of our coastal trip. We had arranged to spend a morning on the Pelagus, a sleek, 7-metre offshore patrol boat run by the marine and coastal division of the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism (DEAT). These were the guys who made sure there would be enough to eat from the sea today – and tomorrow. By all accounts, it looked like an impossible job because of the pressure, both local and foreign, on our fish stocks around the coast. Everyone, it seemed, had jumped into a fishing trawler and was steaming towards “South Africa’s teeming seas,” as National Geographic magazine put it. Factory boats and long liners and ski boats and netters were all about, sucking up the stocks. They came from Taiwan, South Korea, Spain, Norway, Japan and other keen seafood-gobbling nations. A fish war was looming. Today, we were going on a patrol around False Bay and beyond to see what the poachers of crayfish and abalone were up to.

I had never been able to get excited about abalone (known in South Africa as perlemoen), simply because I’d never tasted one. To me, they were slimy ashtrays (the shells make great soap dishes and ashtrays and button pots) but to more than a billion Chinese people their flesh is ‘coveted cuisine’, prestigious wedding-feast side-dishes, prized aphrodisiacs and such. I mean, when is Viagra going to catch on over there? The sooner the better, I say. Then the pressure might just be off our rhinos, seahorses, sharks and perlemoen. Assorted bears and tigers too.

Like the feisty lobster, the abalone used to be poor folks’ food. The wandering Strandloper communities ate them 6 000 years ago and left shell middens all along the coast. In those days abalone were bigger than Texas steaks. Today, the Chinese market likes them bite-sized and box-shaped, neat little portions for high-status events.

And although South Africa steamed into the New Millennium on the tracks of sinking interest rates and unprecedented economic growth, it was still almost impossible for the lower-income groups of the country (meaning most of its citizens) to climb on that particular gravy train and benefit from it. In fact, most poor South Africans didn’t even know where the station was. As we travelled along the shoreline of the country, we heard how some individual wheeler-dealers palmed in millions simply by making a telephone call. Mainly, however, we heard how a family of five was struggling to live on a social grant of little more than the equivalent of US$100 a month. And whether you were a billionaire or a pauper, you paid the same prices at the store.

So, like the Namaqualanders who believed they had a right to their diamonds, the people of the southern coastline poached abalone day and night and sold them to the massive, infinitely voracious Chinese market. The natural stocks of abalone began to disappear. And I hadn’t even tasted one yet.

While we were waiting for the DEAT patrol boat, we chatted to Achmat Hendricks, who was preparing his gear for a day on the waves. His hair was tousled and his eyes were still half-lidded from slumber.

“I sleep on my boat,” he said. “I had a little domestic tiff with my wife – something about who earns more – and so I ended up living here. When the storms come to False Bay, the boat does bobble about, but that’s fine. The only problem I have is when I occasionally sleep at my daughter’s place on land – it makes me really giddy.” Achmat suffered from the well-known ‘disembarkation disease’.

The 58-year-old Achmat showed us the healed furrows of deep cuts on his fingers – the sign of a snoek fisherman who works with hand lines. But, as in all of Africa’s fishing waters, the traditional methods were giving way to the hi-tech ships and boats of first-world owners.

“The fast ski boats with their electronic fish finders are massacring everything here,” he said. “And as for the long liners – there is so much wastage that many of us make a small living by just following them and hauling out the dead fish in their wake.”

Jules and I walked down to the edge of the water, where two raggedy men were hanging gutted, headless snoek out to dry. One of them, David September, said the space under the cold, cement gutting table was his home.

“It’s where I lay my head every night,” he declared, grinning through marvellous gap teeth. “Ali [indicating his mate] and I are the Fish Fleckers of Kalk Bay.” He said it with great professional pride, and then added:

“Can we look after your bakkie while you’re gone?” I said fine.

“And, can we wash it for you, meneer?” OK then.

David September’s face creased around a wide smile:

“Plesier van die oggend! Kar was en oppas!” – The pleasure of the morning. To wash a car and look after it.

I thought that David September, who slept under a concrete table in a storm, could teach your classic Cape Town waitress, an impossibly superior form of life (with the exception of the Long Street variety), a thing or two about the service industry.

The Pelagus pulled up to the quay and Captain George Solomons, a kindly, solid-looking man with searching eyes, welcomed us on board. Leading us down to the galley, he introduced us to the chef, Robert Prinsloo, and offered us a five-star breakfast. On their longer, five-day trips, Robert also had the privilege of being the only crew member allowed a daily fresh-water shower – the rest had to make do with salty sea water.

“Just name it – we’ll prepare it for you.” The tempting aroma of fried bacon and eggs flowed through the galley, but we were mindful of seasickness and declined the feast on offer.

Joining us on the Pelagus was the DEAT marine inspector, Thembiso ‘Osborne’ Thela. The eight crew members, all dressed in orange overalls, were shy, mostly middle-aged gents who had been crewing together for years. We donned life vests and Captain Solomons said:

“My men are just as informed as I am – feel free to ask them anything.”

The day’s mission was to be a ‘visible policing presence’, to check on fishing permits and to keep a sharp look-out for abalone poachers and shark-fin hunters.

“Once we found a boat with 20 dead pregnant sharks on board,” said Captain Solomons. “We managed to cut 26 live babies from their bodies and released them into the waters. Maybe some of them made it.”

The captain left us in the able hands of Chief Engineer Billy Arnold, a nuggety Port Elizabeth man. Was this a dangerous job?

“Being linked to law enforcement makes us a target,” he said. “They’ve thrown stones at me, they’ve mugged me and they’ve shot at me. But we’re not afraid of these people. We’re doing a great job.”

We began cruising down to Cape Point. Jules and I had not packed our sea legs, and we could feel the curry supper from the night before planning a great escape from our bodies. But the story was spellbinding. Did his family ever come under threat from poachers?

“My family is far away,” Billy said. “Even so, I once got a panic call from my wife to say a group of poachers were out on my lawn, calmly having a braai.” It was a clear warning. We know where you live.

China spent so much cash on the abalone that the ‘alpha’ poachers had the best boats, the finest equipment and the biggest engines around. They took cellphones underwater in plastic bags and warned each other when boats such as the Pelagus approached – then they simply ditched the abalone and escaped.

“They send spies to come and see what equipment we’ve got so they can get faster stuff,” he said. This was particularly irksome to him, who took great pride in maintaining the boat’s twin 500-hp Rolls-Royce engines.

We approached Seal Island, the snack spot for the famous great white sharks of False Bay. Many years ago, I’d heard a legend about The Submarine, a shark so huge that they had to manufacture a massive hook especially for it. The hook was baited with ‘half a horse’ and lowered into the sea. After much tugging on the thick line, it came up – horseless and straight as a pin. Reflecting on that tale now, I realise I must have gleaned it from someone who was very drunk at the time.

However, the real angle to the great whites of False Bay is their ‘Air Jaws’ display as they leap through the air to catch seals, their favourite prey. And after hearing how seals ritually ‘de-gloved’ dear little jackass (aka African) penguins, unzipping their pelts from their quivering bodies, I was fully in the great white camp.

Stomachs heaving, Jules and I crawled up to the top deck and met Jerome Fouten, the Second Engineer. Jerome, who had also faced death in the course of his job, didn’t put such a brave face on the matter. We soon found out why.

“A while ago I was hijacked by three guys who blindfolded me, put me in the back of a car and drove me around for about 40 minutes,” he said. “By the time they stopped the vehicle, I was just able to see under the bottom of the blindfold. We were in an isolated, bushy area. One man had a gun. I knew what they were going to do. I elbowed him out of my way, his gun fell to the ground and I ran for my life.”

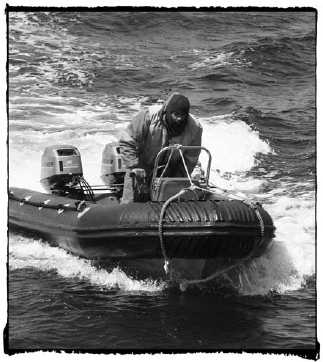

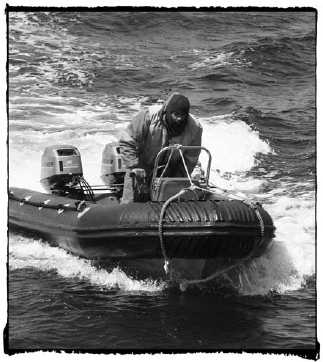

Jerome – younger than the rest of the crew – skippered the on-board hunter vessel, an inflatable dinghy. When they chased a suspect boat, it was invariably Jerome and the DEAT inspector at the sharp end of the quest.

“I’m not armed and I don’t get to wear a bullet-proof jacket,” he said. “I tell the poachers I’m just the taxi driver, they mustn’t shoot at me. Obviously, they don’t listen.”

We bumbled around the Pelagus feeling green, interviewing the working crew, who had all been victimised on land by the poacher communities. A large skiff loaded with happy smiles and a good catch came by. They saw my cameras and began to pose with their fish. Then the seas got serious. I managed to retch and take photographs at the same time. Jerome rescued Jules and pointed her to a cabin where she could lie down. I joined her a minute later. Most of the crew made concerned appearances at our door. Billy came and offered us a shot of Worcestershire sauce, “to settle the stomach”, and it seemed to work.

Then there was action of another kind. Two small boats had been spotted, one of them “suspicious” because it immediately made a run for it. The dinghy was winched down in a flash. Jerome and Osborne hopped in. Jerome pulled a blue balaclava over his head, immediately transforming himself into a rather ominous anonymous person, and they sped off in pursuit of the running boat.

We hauled ourselves up off our pallets and visited the captain.

“It’s not all cowboys and crooks out here,” he said. “Two weeks ago, we took a few divers out to release a whale that’d got tangled in lobster-fishing ropes. You see a thing like that, you really understand that whales are mammals – they’re not just big fish.

“After we freed it, the whale went down and came up again and slapped the sea with its tail before swimming off. I swear, it was saying ‘thank you’.”

A garlicky-chilli kind of aroma had risen from the inner depths of the Pelagus. We went down to the galley, where Robert Prinsloo stood in tears. Slicing onions can be a very sad business. What did the boys like to eat?

“Meat stews,” he said. “Seafood pizzas and steak. Sometimes I bake them a cake.” We left him to his weeping and went to see how the hunter boat was doing. Jerome and Osborne were back. The suspects had escaped.

We approached Simon’s Town. On the flanks of the mountain you could see some really wealthy homes.

“These people,” sighed Billy, his voice laced with more than a tinge of disgust. “Some nights, we moor here. And then they complain when we switch on anything more than navigation lights. It seems the rich find our little cabin lights very disturbing. They think they own everything.”

This left me with subversive thoughts. Billy and his mates get shot at for protecting our natural resources. They often have to arrest members of their own community for poaching – people who don’t really see an alternative way to earn money. And then the rich folks on the hillside – who should be grateful beyond measure – want them to dim their cabin lights. Preferably disappear after sundown. Hmm.

Another crisis had, in the meantime, snuck up on me. While I was trying to photograph the shoreline, something in my long Howitzer-type lens collapsed and was near death. I had to get to Cape Town fast. We thanked the chaps, paid the Fish Fleckers of Kalk Bay handsomely and sped off to the Mother City.

At a stop street in Bishopscourt, a black guy wearing a blonde wig, pink lipstick and a summer dress tried to flog us a joke book, speaking in a quavering, sex-kitty voice:

“Hi, my name is Portia.” Jules could not help mimicking his transvestite tones.

“Actually, I’m Sipho,” he answered in a deep voice and smiled. “I’m just trying to sell these funny things in a funny way.”

We bought one and darted through the traffic to the top of our beloved Long Street, where we handed the long lens in to Uncle Camera Doctor, who promised us he’d operate immediately. We thought we’d have lunch and wait for the patient to come out of theatre.

After our morning at sea, Cape Town lunchtime society found me stinky and unpresentable. A young waitress mouthed the word “scum” to her mate and gingerly handed me a menu. I grinned and ordered something in an avocado.

The next morning we heard some intriguing news. A scuba diver had gone missing off Miller’s Point near Simon’s Town the day before. He had apparently run out of oxygen while diving five metres down. Had he been left behind by a fleeing poacher boat? No one could say. But the three bags of perlemoen found near the dive site seemed to tell their own story …