As the black storm clouds approach from the ocean, the atmosphere around Danger Point lighthouse is electric. Rich afternoon sunlight is offset by nervous streaks of lightning on the horizon. The lichen-splattered boulders leading down to the coastline are split and scored by millions of years of battering by waves. The ocean booms and thuds on the edge of the jagged land, as though demanding entry.

If you stand at the marker below the lighthouse and follow its directions out to sea, you’ll find yourself staring at the exact spot where the troopship HMS Birkenhead went down on 25 February 1852. She was carrying British soldiers, reinforcements for the Border wars with the Xhosa. She was doing about eight knots when she hit a rock just more than 2 km south-west of Danger Point.

The bottom of the ship was torn out. Only three of the eight lifeboats could be released into the sea. All the women and children were ordered into the boats and the men were told to hold back. As the Birkenhead sank, the soldiers and sailors on board tried to swim to shore, and the sharks cruising in the area feasted. Out of the 630 on board, 454 died.

These days, the likes of the Birkenhead would be guided to safety along the southern Cape coastline by the beam of the Danger Point lighthouse, which flashes in short bursts of three. In his eyrie above the shoreline, the lighthouse keeper sees all. Out to sea there are the passing ships and there is the coming storm. Below him, along the paths leading to the water, men come streaming towards their vehicles parked along the main road. They are the perlemoen poachers, and no one gets in their way. They carry their bags of booty – the real sunken treasure around here – with a pirate’s swagger and head off home.

“I see the poachers,” Colin Olivier, the lighthouse keeper tells us. “But it’s not our business to catch them so we stay out of it.”

Abalone. Perlemoen. What’s the fuss? As a Jo’burg-based landlubber I used to see these perlemoen busts on the evening-news broadcasts. There, in the featureless face-brick courtyard of someone’s home somewhere in an industrial suburb, uniformed cops would be dragging out bags of what looked like ashtrays. The TV reporter would tell me that they had a value of millions – there were gangs involved and possibly drugs too – and that the perlemoen were smuggled off to China, where they were viewed as a delicacy. What? I could not see it. To me, a perlemoen was not a living entity. It had no value. Like most South Africans, I had never tasted one.

I remember thinking: Why the hell didn’t we just let the Chinese strip our shores of this stuff and be done with it? Then, with the perlemoen gone, the gangsters would all have to get day jobs and the smugglers would go away. Then I found out a little more about this ‘piece of snot in a crash helmet’ and this is how I think it all goes …

We have massive spreads of kelp forests off our southern shores. Inside these waving, drifting masses of kelp live the Cape sea urchins – Parechinus angulosus – under the prickly spines of which shelter juvenile perlemoen. Many sea beings like to snack on a perlemoen, especially the rock lobster – kreef.

The lobsters are also eating the sea urchins and so are stripping away the perlemoen nursery facilities. To make things worse, lobster numbers east of False Bay are increasing, migrating around the corner of the Cape in vast numbers for reasons no one can quite explain. At any rate, they are playing havoc in the perlemoen beds.

Now, to make matters worse, there are many millions of people in China who love to serve perlemoen on special occasions such as weddings. They want our perlemoen so badly, they are willing to buy it for huge sums on the black market. The attack on the hapless perlemoen is two-pronged.

So the smuggling gangs come from China and approach the local coastal communities, most of whom are living on the under side of the breadline. For them, the perlemoen has been the ‘food of last resort’ for centuries. The beds are plentiful and if there’s nothing else to eat, the boys just hop into the ocean with a chisel and pry them loose from the rocks. Each perlemoen is a meal on its own – and you can even use the shell for a rather pretty ashtray or candle-holder.

Initially, it’s a cash business. The Chinese are paying with fresh bank notes out of the boots of their cars. You suddenly see wealth all over the village, in the form of new Mercedes-Benz models and extensions to the home and pretty things for the women to wear and, perhaps, a better brand of whisky for the man of the house.

In the decades before the 1994 democratic elections in South Africa, only certain lucky individuals were granted permits to take out the perlemoen. But in the New South Africa the ‘formerly disadvantaged’ populations living along the coast firmly believe it’s their right to benefit from the sea and extract as much perlemoen as they want. For most of them, it’s also their only means of survival.

Moving right along from the concept of a perlemoen-for-dollars business, the smugglers now begin to offer the local poachers drugs and guns for the perlemoen instead. This has a certain appeal, because both drugs and guns can be sold for exorbitant profits in the local community. And then a vicious cycle begins. You’ve now got gun-toting drug addicts patrolling the shores around the southern Cape, grabbing anything on the sea bed that resembles a perlemoen, drying the stuff at home in unsanitary conditions and getting a quarter of the price they normally would for a properly dried perlemoen. So more perlemoen are prised off the rocks to make up the shortfall. Cops are outgunned or bribed to join ‘the other side’, tourists are beaten out of the way on the beaches and objecting locals get death threats and gang graffiti on their high walls. And ordinary people living along the coast simply don’t have a chance to eat perlies any more.

We drove through the town of Hawston, near Hermanus. It had, at that stage, not yet been ‘blessed’ by the attentions of property developers, who had created something of an overpriced look-alike condo strip mall along the road into Walker Bay. Another day in Paved Paradise. Not yet here in Hawston, because this was the place, they said, from where the fearless perlemoen gangs operated.

Hawston had snow-white beaches, a lovely bay and wild horses in the water meadows. We had lunch at a new restaurant called Huraeb Gaes: smoorsnoek, vetkoek, oxtail, mussels in white wine and so on. We asked the manager, Judith van der Merwe, if she would prepare some perlemoen for us.

“It’s not the legal season for perlemoen,” the genial woman replied. “I know lots of poachers who are taking them out all the time, and I’d love it if they would do their civic duty and supply me, but they just laugh. They get far better prices elsewhere.”

Just like the shark man, Brian McFarlane, in his youth, the kids around here dived for perlemoen. Some were look-outs, while others helped to carry the stuff from place to place. Very few folk in Hawston had perlemoen-free hands. I could understand it. Supply and demand. A pity about the drugs and guns, though.

The most famous name in connection with perlemoen poaching was that of Ernie ‘Lastige’ Solomons. To many in Hawston, his name was synonymous with that of Robin Hood. He seemed to be creating a new legend every day.

“Ernie has been banned from Cape Town,” someone in the restaurant told us. “But he likes the clubs over there. So he puts on a mini skirt and a wig and goes there anyway. He has also produced a ‘perlemoen rap’ CD called The Six.”

We could not find Mr Solomons that day, but we did meet a famous former poacher called John ‘Klonkies’ Moses. The burly Moses ran a timber-cutting business as well as making money from his legal perlemoen quota under the new system. Under this arrangement, in a bid to reduce poaching, the coastline is zoned and chosen individuals are each assigned an area.

“We know the perlemoen are being wiped out,” he said, “but the issues are complex. For 30 years, only 200 commercial divers were allowed to take out perlemoen and they kept the business to themselves. They were schoolmasters and lawyers and none of their money ever enriched the community.

“I went with 12 other poachers to ask the government to change the situation. We were all poor. We told them: we don’t want to poach, but we will if we have to. They would not give us licences, so then the poaching really began. It became a war.”

John Moses wasn’t talking about a price war or a couple of slaps in the face here. These guys were serious. The numbers were just too big to leave alone.

“I warned everyone – including the media – not to portray us as people with a lot of guns and big amounts of money – but they did. And then the chancers started arriving here – lots of them.”

We told him about our foray with the DEAT patrol boat from Kalk Bay. John laughed.

“Let me tell you. When a patrol boat approached, we would SMS the divers. They had their cellphones down there in waterproof plastic bags. These boats are big and clumsy, you see them coming from far away. So what happens? The poachers throw their perlemoen overboard so there’s no proof. And the perlemoen die. It’s such a waste.”

What about legal, on-shore perlemoen farms?

“Now you’re talking,” he replied, suddenly more animated than he’d been a second before. “We need perlemoen farms here in Hawston. Then we could maybe re-seed the area and make Hawston a Marine Conservation Area.”

Like the cigarette baron who makes his millions from tobacco sales and devotes the rest of his life to the wellbeing of humanity, or the hunter who becomes the conservator, this poacher wanted to become a protector.

“The authorities can’t stop us poaching,” he said darkly. “Only we can stop it …”

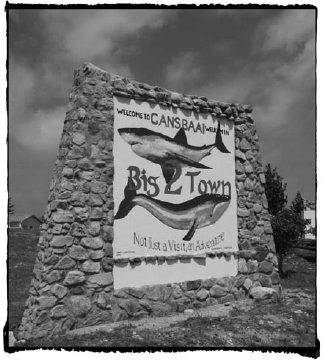

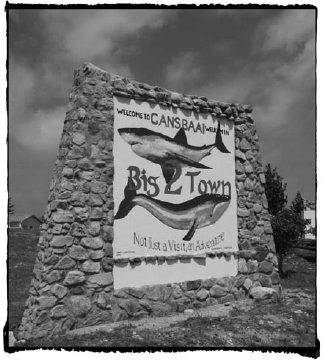

Wilfred Chivell’s place lay just off Poacher’s Road on the way to Danger Point lighthouse. Wilfred – one of the foremost environmental champions along the Cape south coast and owner of Dyer Island Cruises – had offered to host us for a couple of nights as we picked away at the intricate matrix of Gans Bay life.

After our visit to the lighthouse, we returned to find Wilfred’s friend Susan Visagie hard at work in the kitchen on a magic meal involving spiced chicken, cheese toppings, vegetables and something outrageous in caramel toffee. Susan, who was also helping Wilfred plan his new eco-centre in Klein Bay, began laying out a dish containing four thawing pilchards, which I thought was a bit over the top for supper.

“No, that’s for the penguins,” she laughed, and took us outside to where two rather oily and depressed-looking African penguins lurked in a little enclosure. Nearby was a clutch of baby mountain tortoises and, in an igloo-shaped building, a series of swallows’ nests. Wilfred was a sucker for all kinds of strays, even writers bouncing up and down the coast.

“One of my jobs around here is to keep a constant supply of wet clay available for the swallows,” said the inventive Susan.

That night, around the dinner table, Wilfred told us what life had been like around here two years before.

“This town was a free-for-all. The police were escorting the poachers around. Yes, the poachers actually hired police to bring their armoured trucks to load up the perlemoen and take them through the road blocks.

“A friend of mine once came around a corner and saw a few dozen men from Blompark (the local ‘coloured’ village) in wet suits, about to dive into the sea. Then a Casspir drove up and he saw the policeman talk to the divers. The Casspir was then parked out of sight, in the bushes. The divers all went into the water, like a pack of seals. They later brought out their load of perlemoen and it was all loaded into the Casspir.

“I heard afterwards they had negotiated a R30-a-kilo handling fee with the police. So, let’s say they took out a tonne of perlemoen that day – that’s a R30 000 bribe for two policemen who earn maybe a couple of grand a month.

“I don’t blame the guys from Blompark. They see the poachers from Hawston and Hermanus come here for perlemoen because there’s nothing left over there. The local community once believed the government would protect them, but it didn’t. We need a community quota. Locals should benefit from their own resources.”

Wilfred’s young son, Dicky, later told us many schoolkids in Gans Bay were part-time students and full-time perlemoen poachers earning R250 a kilo.

“My dream is to change that around here,” Wilfred said with passion. “The younger generation have grown up with no respect for the sea because of the poaching. I’m putting up a marine centre to teach the kids of the Overstrand, from Betty’s Bay to Pearly Beach, about this.

“I never used to associate Gans Bay with perlemoen poaching and drugs. I thought we were different from Hermanus. But I mean, suddenly there’s R1 million on offer. How else can you make that kind of money so fast? Then you’re breaking the law anyway and you look at other ways of making money, like drug dealing. Then you need to keep it all safe so you get guns.”

The next day Wilfred took us to the perlemoen farm near the lighthouse, where I discovered that a perlemoen actually lives and breathes, a bit like you and me. I had a tug-of-war with a young perlemoen. We fought over a small piece of kelp and he won. I have to say I was nearly asleep at the time, having downed a couple of anti-seasickness tablets that morning before our outing with Dyer Island Cruises, followed by a brace of delicious beers for lunch. Alcohol and no-heave medication bring on drowsiness far more thoroughly than two hours of chamber music.

Nick Loubser, manager of the I&J perlemoen farm, took us to see his breeding stock. I became hypnotised by the stately movements of a perlemoen and its tiny eyes.

“These guys are tame,” he said. “They get used to people. Here, try feeding one.” And so I – in that dream world between sleep and wakefulness – tussled with a rather muscular perlemoen. Lillian, Wilfred’s sister, who worked in the packing section, said she was glad the perlemoen were exported live from the farm.

“I’ve become very fond of all of them,” she said. “I would hate to actually see them killed.” That’s a lot of personality for a glorified ashtray, I thought.

Perlemoen farming is pretty clean. They don’t produce protein-enriched waste, like fish do. They eat kelp, carefully harvested by local concessionaires so as not to destroy the beds. Hundreds of tonnes of these perlemoen are legally shipped off to the Far East in a kind of semi-hibernation state, which lasts for 42 hours.

This appeared to be the optimal future for the perlemoen industry of the southern Cape coast.

We liked John Moses’s ideas of local communities benefiting from perlemoen farms and trying to re-seed their coastal beds. Then the perlemoen business would have completely ‘clean hands’ and China could buy its wedding delicacies over the counter and the poachers and smugglers could all get legitimate jobs. And the drugs and the guns could all go away. And the lighthouse man would feel a lot better about working the night shift …