When I think about the Morgan Bay Hotel, a cockatoo called Baldy and a woman called Dodo spring to mind.

We’re trying to have a beer in the courtyard of this old hotel, shortly after checking in. A sulphur-crested cockatoo is doing his nut in the corner, screaming like a midnight drunk. He whistles and yells and spins and performs daring somersaults around the rope inside his cage.

Baldy’s been there for 17 years now, shouting the odds at no one in particular. They sometimes let him roam through the hotel like a maddened banshee. And if one neglects to compliment him on his magnificent singing voice or hairstyle, Baldy does odd things like ripping the rubber trim off the windows.

He is often to be found in the bar after supper, scrounging peanuts from the guests. Give him an opened tin of tomato cocktail and he’ll grip it firmly in his beak and down the lot. And then you must applaud his drinking expertise.

This hotel was all about serious repeat business. The icon of the ‘come-again’ crowd at the Morgan Bay Hotel was one Mrs Dodo Wilmot. The Wilmots had been vacationing here for six decades. Every year, they booked Room No. 2. Mrs Dodo Wilmot, now a widow, arrived here and met up with her son, who flew in from his home in the USA for a two-week family holiday.

“Mrs Wilmot is the first in for breakfast and supper,” the owner-manager Richard Warren-Smith told us over tea one afternoon in the expansive old sitting room with the sea view, where, on a good day, you could see hundreds of dolphins leaping up through the breakers. “She’ll stand there tapping her foot if we’re one minute late.”

After World War II, Richard’s grandfather Ivan returned from hostilities and wanted nothing more than to run a beach hotel on his beloved Eastern Cape coast.

He chose Morgan’s Bay, which had been a holiday village since the early 1900s, when settler families trekked here in their ox wagons, bringing ‘food on the hoof’ in the form of cows and sheep. In 1920 a retired hospital matron opened a boarding house in Morgan’s Bay. She tried selling it, but there was no shortage of shysters in the area, so she had to take the house back a number of times. And then came Ivan Warren-Smith. He caught a bus up from East London, walked to the top of the hill overlooking the bay and fell in love with it all. Maybe the dolphins were showing off that day.

Ivan paid the matron £4 000 for her boarding house, parked his Oldsmobile and caravan on the premises and began turning it all into his dream hotel. It morphed into the Warren-Smith family business over the generations. As a young man, Richard went to London to work in the hotel trade as preparation for eventually taking over the Morgan Bay Hotel. It was just too damned cold over there for the boy from Kei Mouth.

“When I came back in 1990, my father Jeffrey just passed me the braai tongs at a hotel lunch and said carry on,” laughed Richard. Thus he joined the hotel’s management team.

The Morgan Bay Hotel was “like coming home” – true to its motto. South Africa lost something from the ’60s onwards, when many of its family hotels gave way under the onslaught of franchise operations. Jules and I were delighted to run across establishments where the dining rooms were still vast, the menus short and the manager not too snooty to sit down and have a drink with the guests. Where you stepped over sleeping old dogs at the entrance, the hotel cockatoo ruled the roost and the information booklet requested “the more jubilant guests” to be quiet at the poolside in the early afternoon.

The next morning we left on our Wild Coast ‘amble’ across Kei Mouth and up to our next stop, Trennery’s. A cheerful young man called Bongani Colonial Mlilwane, who had 15 siblings and lived nearby, was our guide for the first half of our 14-km walk.

Colonial said he was in heaven every day.

“I used to work as a school security guard on the Cape Flats,” he said. “I lived in a shack. I saw gunfights and shack fires until I thought no, it’s time to go home. Now I walk up and down the beach, talking to my guests. What could be more pleasant?”

Prompted by various sightings of abaKwetha along the way, we asked Colonial about his personal initiation to manhood, which involved a painful bush circumcision.

“I was with a group of friends all doing this thing together. Our wounds were bound by absorbent leaves, which were changed every 15 minutes. We were each given a new white blanket with red stripes. We were warned: the headman does not want policemen or ambulances coming here.

“You are not a man if you have to go to a hospital, they said. By the fourth day, you feel so much pain and you have no strength and you do not care if you die.”

In the first week, the initiates covered themselves with white clay and slept in designated huts. Sisters could bring them food or firewood but on no account were they to see their mothers. After four weeks – God willing – they were healed.

“A goat is slaughtered and prepared for you,” said Colonial. “You drink beer and you are allowed to cross the river and hunt. It is a big thing to become a man. No woman would think of marrying you if you were uncircumcised. And if you are not, you remain a boy, no matter how old you are.”

We were suddenly at the swine-fever control point on the Kei River Mouth. I’d been living in Colonial’s head for more than an hour, viewing out-takes from his world. We came across a jovial, middle-aged squad of South African and Brit hikers, heading south on the ‘amble’. They were doing the long trek from Kob Inn to Morgan’s Bay. Colonial took over their group from Eric Nkonki, who became our guide.

We crossed the Kei River by ferry, a large-bottomed boat expertly manhandled by a team who twirled giant wheels attached to rudders and outboard engines.

Then we were in the old Transkei. And the weather was also from another country. It turned grey and foul and windy in no time at all. The morning’s jaunt had turned into The Lost Patrol. We trudged, looking down and saying nothing in case of sand-in-mouth, against a vicious headwind. We were joined by Eric’s friend, a guy called Amos, who wore very fancy leather shoes. So fancy that, when we crossed little rivers and streams, he prevailed upon Eric to piggyback him across.

“Here is the Gxara River,” announced Eric. “Do you know this place? Up the river is the pool where the Nongqawuse went, where she was given the vision.”

We’d been reading Noel Mostert’s epic Frontiers, detailing the demise of the Xhosa nation in British colonial times, and The Dead Will Arise by Jeff Peires, which told the story of the infamous cattle killing of 1857.

Reel back to just before 1820, as more than 300 000 unemployed soldiers who’ve fought Napoleon’s armies sit idle in grubby, disconsolate, post-war Britain. An advertising campaign is launched to encourage at least 5 000 Britons to come and live in South Africa, “the most precious and magnificent object of our colonial policy”, according to The Times of London.

They’re supposed to be agriculturalists, destined for the border lands of the Eastern Cape. But many tradesmen, artisans and mechanics pretend to be farmer types and make it onto the transfer list. A fair number of them fail as farmers, but end up building magnificent settlements such as Grahamstown instead. These families, faux farmers and genuine, are the buffer zone between the Cape Colony and “the warlike Xhosas”, as some like to call them.

Now fast-forward 34 years through a number of bloody frontier wars to 1853 and to the landing of a smallish herd of Friesian bulls from Europe at Mossel Bay. They’ve all got the dreaded lung-sickness and are rotten from the inside out. Within two years, this disease has spread all over the colony and up through Xhosa country.

Three years later we’re in April 1856, at a pool on the Gxara River in the company of two young girls, Nongqawuse and Nombanda. Something happens at that pool on that day, something that is still the subject of heated debate today, nearly 150 years on.

Nongqawuse’s uncle, Mhalakaza, has been working for the Archdeacon of Grahamstown, Nathaniel Merriman, on the cleric’s travels in the hinterland as his travelling advisor and translator. Mhalakaza has cherry-picked more than his share of biblical Christian knowledge, imagery and philosophy from his boss. He blends this with his inherent set of Xhosa principles and becomes something of a grand speechmaker himself. Merriman’s wife insults Mhalakaza one day and the Xhosa leaves their employ and goes back to his homestead on the Gxara River.

We’re with the girls at the pool, and Mhalakaza is lurking somewhere in the dramatic background. Two men claiming to be long-dead Xhosas materialise from the bushes. They tell the girls to pass on the message: there is going to be a ‘rising up’ and a rebirth of the Xhosa nation. All cattle are to be killed. The cultivated fields are to be burnt. Corn storage bins are to be trashed. Fresh kraals are to be built. ‘New people’ will rise from the sea with healthy herds of cattle for everyone. Whites and Fingoes (who side with the British) will be swept off to sea and disappear forever.

The Xhosa nation is divided into believers and non-believers. The believers destroy their food stores and their cattle herds. You can smell rotting meat all over the frontier. Fires rage all over the Eastern Cape. A nation waits. The non-believers say, What? You want me to do what? Kill my precious cattle? Burn my food? Believe a couple of teenage girls and their angry uncle?

Various appointed days “of the two suns rising red” come and go. Mixed in with all this prophecy and madness is the news that the Russians have smacked the Brits in the Crimea and that those same Russians are on their way to help clear out the governor, Sir George Grey, his cronies and his ‘buffer zoners’.

Nothing happens. Mhalakaza manipulates the situation. He says the ‘new people’ aren’t quite ready. Vision begets vision. The tips of thousands of cattle horns are spotted just under the reeded wetlands, supposedly waiting to emerge in their boisterous, bellowing masses. King Sarhili is sucked into all of this. He, like his people, is so desperate to see the backs of the white settlers and their soldiers that he’ll believe anything.

By January 1857, doubt sets in. This is partially dispelled by a new edict from Sarhili announcing that unless all the cattle in the Xhosa kingdom are slaughtered, the prophecy will not come about. More killings. But who’s actually in charge around here? Sarhili or Mhalakaza, who is starting to sound a little like a crazed egomaniac?

Sarhili tries to commit suicide but is stopped in time by his councillors. And on January 17 he speaks up at a beer-drinking session:

“I have undertaken a thing of which I now entertain certain doubts, but I am determined to carry it through.”

A month later, when the starving begins in earnest, King Sarhili says:

“I have been a great fool in listening to lies. I am no longer a chief.”

The Xhosa nation begins to starve in their many thousands. Their kraals stand empty and they begin to filter into settlements such as Grahamstown and King William’s Town. People die in the streets where they fall.

We finished our rest on the Gxara River and prepared to continue the windy trek up the beach. I suddenly remembered Sir George Grey and his wife, Lucy.

According to history, Grey might not have had a direct hand in the cattle killing, but the results played very much into his ‘social engineering’ hands. He now had the tottering Xhosa nation where he wanted it: squarely behind the begging bowl. He could dispense food relief to whomever he wanted. He could send Xhosas all over the country, where their labour was gratefully and cheaply used on farms, in factories and in homes.

But Sir George Grey’s comeuppance is his wife, Lady Lucy Grey, and her dalliances. He is recalled to London and, upon his arrival, the new Home Secretary sends the Grey family right back to Cape Town. Sir George gets another turn at the wheel of governance.

I have Jeff Peires to thank for the basic detail of what follows.

They’re in the ship headed south again. Lady Lucy, the naughty girl, sends a note of assignation to one Admiral Henry Keppel, a fellow passenger she rather fancies.

“Unlock the door between our two cabins and I will come to you in the night,” she urges the admiral.

Unfortunately, Sir George intercepts the note. He loses it entirely with Lucy, forces the ship to dock at Rio and has her kicked off at the docks. It is not generally known if Lady Lucy falls in with the party set down at the Copacabana. But she doesn’t see George for 36 years.

On the verge of insanity, he returns to the Cape. Instead of another bout of social manipulation (perhaps turn the Boers into vegan-liberals or something) he is so caught up with the Lady Lucy affair that he can do nothing but drink, curse her name and look for ‘victim sympathy’ in Cape Town society. The irony is delicious. Try as one might, it’s hard to picture what is left of the Xhosa nation shedding a single tear of pity for the plight of Sir George.

By the end of 1858, the Xhosa population of British Kaffraria (the Eastern Cape border lands) had dwindled from 105 000 to fewer than 26 000. Huge swathes of former Xhosa territory, including their spiritual stronghold, the Amatola Mountains, were given over to the white settler communities. In fact, many Xhosa ended up working for these settlers on land their clans had once owned.

But I wasn’t there at the time, and I still had so much to read and learn about the whole Eastern Cape frontier. It was no use pointing fingers in hindsight at anyone. Except, maybe, at the players in the Lucy Grey scandal.

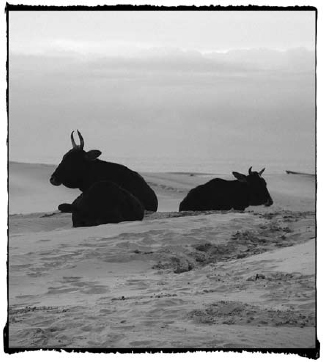

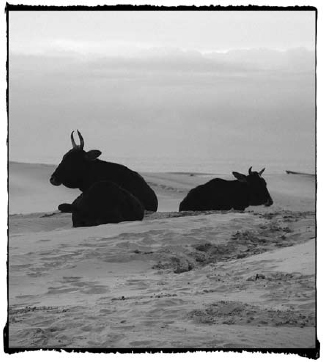

On we walked, The Lost Patrol, until we came to a spot where some cows lay on the beach, looking utterly stoned. I photographed them and the pictures came out all Kubrick and soft-focus, because I’d forgotten to clean the coastal fog off my lens first. But the hotel was in sight, my legs were sore and the backpack was eating at my shoulders. I had been taking special care not to wobble onto the rocks we had trudged over.

There was only one mud puddle in the dirt road leading up to Trennery’s Hotel. Somehow, I managed to slip gracelessly into it, sinking to my knees in the black muck.

“I just love hiking,” I gasped at Jules, who stood over me with a smile on her wicked face. “But you know what I love even more? When the hiking’s over …”