The summer of ’79 finds me in Port St Johns for the first time in my life. It’s a press junket to celebrate the launch of Capital Radio, the rebel rock station broadcasting from the Transkei bantustan into the old South Africa. The Capital Radio studio is installed in The White House, a hilltop mansion overlooking the port.

Very exciting, this. In the oppressively boring era that is Grey Shoes Apartheid SA, we cling onto anything new and challenging. An East Rand stripper bares all on stage and dances with a python. Bootleg copies of Last Tango in Paris do the rounds. The banned words of jailed poet Breyten Breytenbach are read to small groups late at night. And here’s a brave little radio station that is going to send us, at last, unfiltered news and music. Broadcasting from a town that has always been frontier chic, designed for vagabonds, traders and drifters. And for me, I think, usually when I’ve had too much to drink.

As we troop into The White House, two of the engineers cull me out of the media group.

“Have you ever tried Lusikisiki Lightning?”

“What’s that?”

“Come with us.”

Goodnight Irene. I smoke from the bong of mystery. The fine Pondo tetrahydrocannabinol and its 60 cannabinoid cohorts jump onto some friendly receptor molecules and ride my Neuron Highway down to Synapse Junction where they calm my fevered brain, offer some cosmic insights and give me the utter munchies.

“You’ve been very quiet this weekend,” says my old friend Gwen Gill, the Sunday Times columnist.

“Yes I have,” I reply, peering down through a puffy peppermint cloud as I float past the hotel reception. “What’s for supper?”

Port St Johns had, over the decades, developed a devilish reputation that was bringing backpackers in by the thousands. They came for the hiking and the beaches, of course. It had nothing to do with the fact that Pondo Poison (or Lusikisiki Lightning) was the best dope in the world. The South African marijuana industry was worth in excess of US$1 billion, and Port St Johns had a fair chunk of it.

Over the years, some rather funky economists backed the suggested decriminalisation of dagga. It would add a pile of cash to the GDP of South Africa. One could ‘sin tax’ it in the same way one did booze and cigarettes and possibly buy a whole bunch more submarines and snazzy jets. Which was still a sore point among taxpayers.

These same economists stated that currently the growers received very little for their crops, most of the profits going to the iniquitous ‘middle man’. But if it were legalised and controlled, it could be the saving of the rural population. Which is what they were saying about the poor coca farmers in South America as well.

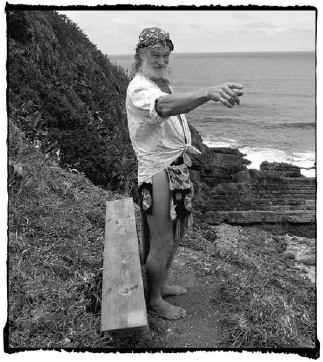

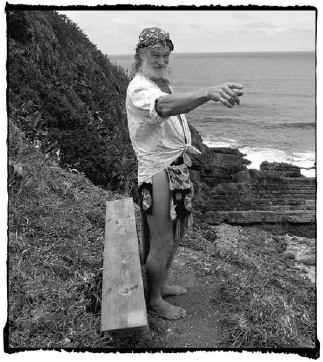

Nearly a quarter of a century later, Jules and I met Ben Dekker, who looked like Robinson Crusoe’s love child. Ben, all two metres of him, had been part of my South African experience since I could remember. He’d been just about everything except a fireman and a cowboy in his life: politician, actor, lumberman, Masters student, demon surf lover, castaway and complete character. But I mostly remembered Ben as being a lovable refugee from The System we mere mortals were trapped in.

The first time we encountered him, Jules and I hid from Ben Dekker. Dressed in traditional headscarf, beaded waistcoat and leather flap over short-shorts that displayed, in Jules’ words, “a vast expanse of muscular thigh”, he strode past us on the porch of Lily’s Lodge at Second Beach like a gaudy ship in full sail. Maybe tomorrow, we said to each other, and lurked in the shadows.

We sat outside quaffing beer and cider, watching the circling frenzies of black bats. I went into the pub called Ben’s Bar to get more drinks. The legend turned to me and said:

“Take your lady and look at the full moon tonight.”

I did, and it was quite magnificent, that perfect orb of cratered blue cheese with its rainbow ring.

The next morning we ran into Ben on our way to town. He was dragging a piece of firewood. We formally introduced ourselves and made arrangements to meet later. At exactly five o’clock we arrived at his cave just off Second Beach. He was working on a sneezewood sculpture. He made some tom from finding the ‘inner shape’ in a piece of driftwood, settling it on a plinth and selling it as sea sculpture. I’d seen far worse in the northern-suburbs galleries of Jo’burg.

Ben was busy turning driftwood into the creatures of local myth and superstition: the snake, the one-legged lightning bird, the baboon (the witchdoctor’s familiar) that is ridden backwards and the strange three-legged tree hyrax.

He gave us each a goblet of Tassenberg Red and we discussed his latest river romp, which had landed him and one Loretta Toon in court on charges of public indecency. He smiled like the old rogue he really was.

“I was trying to save her from drowning.”

We continued our encounter at Lily’s over dinner. We had juicy filleted cob. Ben wandered in from the kitchen bearing a large plate loaded with umngqusho, laced with calamari and crayfish sauce. We admired his magnificent beaded waistcoat. The hippie in me shoved my inner yuppie out of the way and really wanted one as well.

“Gail at Pondo People, a local craft shop, gives me a new waistcoat every year on my birthday,” he said.

“And what happens to the old one?”

“They go to a current lovely lady,” was all he’d say. How could the magistrate fine such a discreet gent R200 for public indecency? It didn’t seem right.

Jules asked him if he had a cellphone number, so we could occasionally contact him from Jo’burg.

“I had one once,” he said. “But I threw it into the sea and told the crayfish to phone when they were ready for me.”

That was all back in 2002. Now we were at his door (so to speak) again, on the Shorelines trip of 2005. But he wasn’t home. Instead, there was a note on the window of his shack that read:

“Sergeant Naidoo, I waited until 11.30. Now what?”

We drove back to Port St Johns to look for Ben. We didn’t have to go far. There, on the dirt road, was the incredibly tall, loping figure of Mr Dekker. We stopped, reintroduced ourselves and offered him a lift to town. He said he remembered us and was happy for the ride. Jules opened the back door of the Isuzu for him.

I thought he had climbed into the bakkie, so I drove off. Jules yelled at me to stop. He’d just started folding his massive frame into the small crawlspace (which is all the backseat of a 2003 Isuzu bakkie really amounts to) as I pulled off in first gear, nearly damaging the man seriously. I was very sorry. Ben was very gracious.

“Good grief,” I later gasped at Jules. “I nearly killed the icon of Port St Johns.”

The big news of this visit was that Ben had just turned 65 and was eligible for a state pension.

“Which is great,” he enthused. “Now, once a month, I can go stand in a queue with all my friends and get some money.”

Ben was obsessed with helping the local AIDS orphans and was teaching them to cut firewood and catch crayfish to sell to visitors. He had also discovered the dangerous joys of self-publishing and could occasionally be spotted using a photocopier at a local newspaper’s offices, running off editions of his thoughts.

Ben was a well-travelled philosopher and you ignored his point of view at your peril. But there was also mischief in the man. Standing near his excellent outdoor toilet (one of the finest loo-views in the world), he pointed at a distant cave.

“About a year after nine-eleven, I started a rumour that this was Osama Bin Laden’s hideout. Not long after that, the CIA came to have a look.”

We asked him why he liked to live next to the sea.

“The accessibility of a huge bath. The rhythm of it. And all that seafood …”

Ben gave us perfect directions to our next stop, Mbotyi River Lodge, and on the road to the infamous Lusikisiki we stopped and bought an excellent wicker briefcase from a guy called Jongilanga Cwangula. Just before Lusikisiki, we turned off onto a long, extremely irksome concrete road with hidden ‘traffic calmers’ that enraged me. And then we were in the peaceful haven of the deep-green Magwa Tea Plantation on a road lined with stately blue gums.

The tea plantations gave way to the Mbotyi State Forest, verdant, dark and mysterious. The road wound down and down, through trees and dripping vegetation. A great storm had knocked down several trees across the road, and we silently wound our way around them.

Mbotyi River Lodge was a leader in the field of responsible tourism and had brought tangible benefits to the local community in its recent past.

Once we’d checked in, I challenged Jules to a quick game of darts and won. We stopped when she started making holes in the ceiling. The afternoon settled into a drizzle and we sat on the wooden porch outside the room, looking down the river into mists.

This is where the straggling, haggard survivors of an East Indiaman called the Grosvenor would have passed in August 1782. Captain John Coxon, who apparently couldn’t navigate for shit, thought they were nearly 700 km out at sea when in fact they were dangerously close to the rugged and rocky shores near Waterfall Bluff.

Crunch. The ship hit an outer reef, just 400 metres from the beach. A couple of people were drowned getting ashore, but 123 found themselves in a sudden, unscheduled African transit lounge called The Wild Coast. The wreck of the Grosvenor is one of the most famous castaway stories in southern African legend.

Firstly, let’s deal with the treasure thing. There were more than a dozen little parcels of diamonds on board, mostly kept by Captain Coxon. Nearly 150 years later, way down south in Kei Mouth, a retired seaman and prospector called Johann Sebastian Bock had settled on a piece of leased land. One day his son John came upon a shiny, rounded pebble and showed it to his dad. Bock Snr saw it was a diamond and he pegged his claim. Soon enough, more than 300 diamonds were uncovered on the property. Most of the diamonds were duly registered. Eyebrows were raised. This was not diamond-bearing land. Bock was up to no good. They charged him with “salting” his land using uncut diamonds.

The truth of the matter was, it seemed, that these were indeed Grosvenor diamonds, brought here long before by one of the survivors. They were very hard on Bock, and sent him to jail for three years. It was a crippling prison sentence for an old man of 73, and he broke down and wept in court.

The real mystery of those diamonds, in our opinion, lay in a later development. They were all in a bottle, submitted as evidence in court and then sent to Kimberley. No one could tell us what happened to them after that.

But back to 1782 and the castaways on the beach. They had no gunpowder, they misguidedly flew the Dutch flag as they walked (at that time the local Xhosas still remembered the Dutch – and not in a nice way – from the First Frontier War) and their captain had lost all his spirit. They were easy pickings for the tribes living along the coast. Only 18 of the original party made it back to safety.

Along the way, some of them met up with the followers of Sango, who had married a white castaway many years before. In exchange for a gold watch-chain, the tribesmen gave them a young ox. The Grosvenor passengers ate the ox and wore its hide on their feet. This was one of the few kindly interchanges concerning any of the Grosvenor survivors and the local populace.

More than 20 years before, a little blonde castaway – a white girl of about seven – was discovered by people from the Bomvana clan, who now live around the Coffee Bay area. Some said she was a “frog, having jumped out of the water”. But most thought she was a magical princess and took her into their hearts. It was she who became Sango’s wife.

Other children along this coast were not so lucky. In 1967 a missionary family, the Grays, came to Mbotyi on holiday. At some stage Gray and his eldest son were left to mind the smaller kids, Vinny (six) and Susie (four). They went fishing instead, leaving the family servants to mind the children.

They later returned to find both Vinny and Susie missing. A local called Eleanor Grant remembered:

“Word soon spread that these missionary kids had disappeared. A massive search party gathered and everybody searched the hills, sand dunes and shoreline. The army was called in and the lagoon was dredged. The children had vanished into thin air. To this day nobody knows what happened to them.

“For months afterwards, the Gray family would wander the hills calling out for their lost children.”

In the early 1980s, the daring bank robber and former policeman André Stander had used the village as a hideout while the rest of the country looked for him. Stander, son of a cop general, would rob three banks on a good day. The members of his gang were eventually shot or captured. Stander himself was shot and killed by a Fort Lauderdale police officer in the USA. We spoke to Jennifer Ludidi, the head housekeeper at the lodge. She remembered Stander from his days as a policeman in Kokstad. She had no idea he was a fugitive from justice when he arrived one fine day in 1983. She noticed that he unpacked his meat into the freezer and his beer into the fridge but did not leave his clothes behind when he went to swim in the sea with his dogs. It was only when the police arrived, enquiring about a man wearing a wig, that she realised Stander was in trouble. She never saw him again.

Our best story-keepsake from Mbotyi River Lodge was the Tale of the Untaken Teaspoon.

In 1993, one of South Africa’s most beloved and charismatic new leaders, Chris Hani, was assassinated by right-wingers. It is no exaggeration to say that the country was ready to burn. It took massive work from Nelson Mandela and a number of other former Robben Island prisoners to calm the general populace. Out here in the former Transkei, the situation was particularly tense. Jennifer remembered:

“It was in the month of August. So many people were toyi-toyiing. The guests departed in a hurry. Some even left their cars here and were picked up by aeroplane at the airfield at Magwa Tea.

“We made the beds, we laid the tables, but the hotel was closed.” Two watchmen were appointed and the hotel remained as it was, trapped in political aspic for eight years. From time to time, Jennifer would return to dust inside the hotel. Sometimes she would be paid a little extra to spruce the place up when a prospective new owner came to have a look. But there were no takers. This part of the world was on simmer.

The locals in Mbotyi went through lean times of diminished income. They occasionally sold a crayfish tail to one of the whites brave enough to spend time at a holiday cottage.

“But during that time, not a window was broken, not a teaspoon was taken,” said Jennifer proudly. “People from Mbotyi are just like that. We don’t take what is not ours …”