Back in the late ’90s, my father informed me that he and my mother were off to live in a city called “Baku.” I stared at him, convinced a hidden camera was going to appear out of nowhere and an over-eager television host would leap out of a nearby closet, point a microphone in my face and howl at my incredulous expression. “There’s no such place!” the host would exclaim excitedly, “we made it up!” And then we’d all laugh and laugh.

However, it was no joke: my dad had received a job opportunity located in the capital of the Eurasian country of Azerbaijan, so off my parents went. They lived there for two years, and while residing in the recently war-torn region was at times challenging, they loved every minute of their experience there and made dear friends in the process.

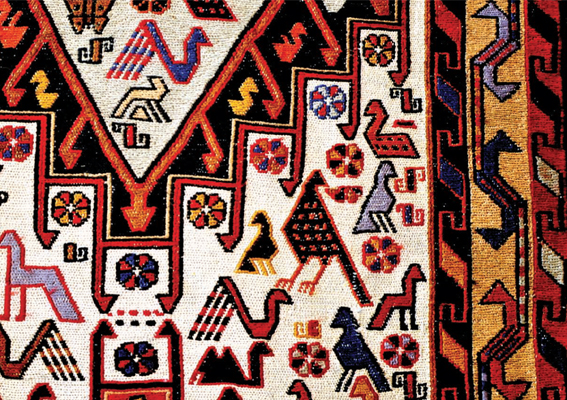

When they finally moved back to the United States in 2000, I stopped by their new home to help them unpack. I was stunned when my father opened the door, and I walked smack into a wall of rolled-up woven rugs, piled high in the family room.

“Did a bit of shopping while you were there, did you?”

He laughed.

“Yes. Azerbaijan is known for its rugs. It’s actually an ancient center of carpet-weaving.”

“Who knew?” I ran my hands along the intricate, tight knots of one of the rugs, admiring the startling colors and vibrant design of the carpet. “They’re beautiful.”

“They really are,” he agreed. “But they’re not perfect.”

“What do you mean?”

“Apparently the weavers, like most weavers of the region, intentionally weave in a flaw during the process of designing and making the carpets. It’s a way they acknowledge that only Allah is capable of making anything perfect.”

“Hmm,” I murmured, my attention returning to the large pile of carpets. “Well, they might be flawed, but they look pretty perfect to me.”

Other than occasionally trying to find the flaw in my parents’ carpets whenever I visit their home, I had never given this conversation much further thought until one day, I was at lunch with a friend. We were doing what girlfriends usually do: we caught up on each other’s lives, discussed our families and at one point, I’m sure one of us mentioned how different our bodies are from when we were in our early twenties. “You know what, though? My concept of beauty has totally changed as I’ve gotten older,” I said, suddenly. “I mean, have you ever noticed that sometimes at a party the woman you can’t take your eyes off of isn’t beautiful in the big-boobs-tiny-waist societal definition of the word? And yet there’s just something about her that’s just breathtaking.”

“Like wabi sabi,” my friend said.

I started to giggle. “Wabi-huh? Sounds like bad sushi.”

“Wabi sabi,” she repeated. “Haven’t you heard of it? You’re half-right — it is Japanese. It’s the idea that there is beauty in imperfection. It’s actually pretty common in Eastern design — it’s the theory that an irregular teacup, or one which has an aged patina, is more beautiful than a symmetrical, new teacup.”

I recalled the conversation I’d had with my dad about the Azerbaijani carpets and told my friend about the concept behind the weaving.

“Sort of like that,” she responded, “except it’s not really about God as the only being capable of creating perfection, so much as it is that imperfection is often perfection.”

Imperfection is often perfection.

When I returned home after lunch, I sat in front of my computer screen, lost in thought. I reached for my keyboard, intending to do a bit of research on the concept of “imperfection as perfection.” The phrase seemed oxymoronic in today’s society of only valuing beauty in perfection, particularly when it came to the appreciation of the female aspect. Nonetheless, I was reassured by the Google results: the concept of flawed beauty as an ideal is an old one. I learned that the Azerbaijanis weren’t the only carpet weavers who included flaws in their work: Persian rug makers do the same, and sometimes Native American weavers include a flaw to “release the carpet’s spirit,” and “allow it to roam.” I also discovered that there were many different interpretations of the phrase wabi sabi: “beauty that treasures the passage of time,” “imperfect or irregular beauty,” and even “the patina that age bestows.”

Imperfect or irregular beauty. I wondered.

Beauty that treasures the passage of time.

I looked down at my own body. I thought of how many years I’ve spent starving it, criticizing it, wishing it was replaced by a newer, more perfect version (something like Halle Berry’s would do nicely). I thought about how much it had changed over time: the lines that appeared, scars I’d earned, blemishes and defects that seemed so huge in my mind, dimples where there had been none before.

What would happen, I wondered, if we lived in a society where all of the flaws — the age spots, the wrinkles, the extra pounds — were actually viewed as badges of honor, as marks of a life well-lived? What if scars, marks or other characteristics of our bodies, the ones that make each of us imperfect, the ones childhood schoolmates made fun of, the ones we tried to hide, were instead valued and celebrated? What if we chose to see them as the source of our individuality, our power?

I think our world would be an entirely different place. I suspect drug abuse and alcoholism would go down; depression would drastically decrease. The psychology and psychotherapy industries would crumble, and the pharmaceutical industry would merely limp along. Racism, ageism and sexism would disappear and discrimination of all types would vanish. There would be no wars, no eating disorders, little crime. People would be kinder and happier. And there would be cupcakes for everyone.

Well, at least most of those things would be true.

Since that day, I find myself watching people, examining the faces of strangers — trying to do so secretly, surreptitiously — and spotting their beauty. It is surprising how easy it is to find.

Her hair, I think. It’s like strands of spun, white silk.

His laugh lines — they make his face appear so kind.

Her beautifully lined hands. Her hands have seen the world. Her hands could tell stories.

I’ve discovered that when you take time to look for a person’s physical beauty, without exception, it’s easy to identify. It becomes obvious that everyone is wabi sabi — every single person is imperfectly beautiful.

It was always this way. It will always be this way.

We just have to look.

“I’m different because even though I have crooked teeth, I’ve never been too shy to smile.”

“I’m different because I’m unafraid to be completely me, including the loud laughter, the bad singing, the good and the flawed. Truly and completely me.”

“ I’m different because I have turned procrastination into an art form.”

“I’m different because even though when I was little kids made fun of my lips — they called me ‘Fish Lips’ — I love my lips now.”