When I moved to the United States from Trinidad as an adolescent, I quickly discovered that my family and I didn’t speak the native tongue. While the official language of Trinidad is English, I learned that Trinidadian English is nothing like American English. This fact was never brought home to me so quickly as one day during my first few days at my new American school, when I found I had made a mistake on my math work.

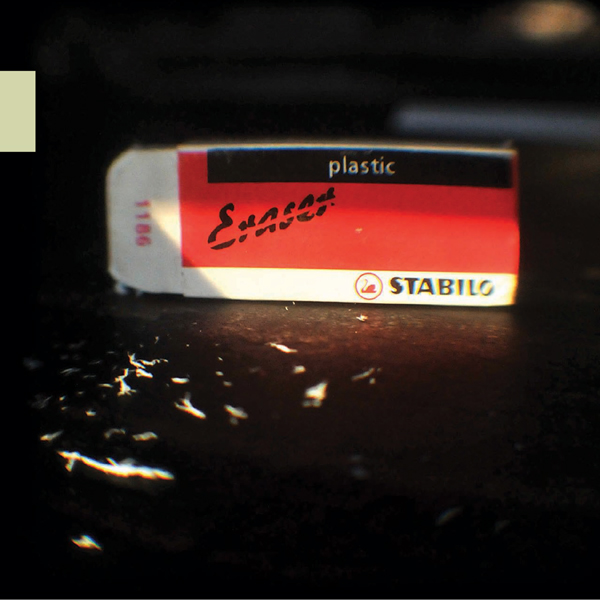

“Excuse me,” I said, whispering to the boy sitting next to me. “Do you have a rubber?”

“What?” he practically shouted. “What are you asking me?”

I was completely confounded. “A rubber,” I repeated, looking at him as if he’d fallen out of a tree. “You know, I made a mistake. I need to rub it out.”

“Oh.” He looked visibly relieved. “Here. And by the way, it’s not a ‘rubber.’ it’s an ‘eraser.’ A rubber is a condom.”

In truth, at eleven years old, I didn’t know what a condom was either, but a quick explanation from my embarrassed mother cleared everything up.

My favorite example of my family’s lack of fluency, however, comes from my father. He was visiting West Texas on business, and his work colleagues had introduced him to that ubiquitous southern breakfast, biscuits with gravy. The next morning, my father’s colleagues returned to Houston, so my dad found himself dining alone.

“What’ll it be, hon?” asked the waitress in her southern drawl.

My father couldn’t remember the name of the dish he’d had the day before, but was certain the word “biscuit” couldn’t have been in its title, since in Trinidad, a “biscuit” is a cookie. So he described it the best way he knew how: “Um, I’ll have your buns covered in gravy, please.”

It is to my continued wonder that he wasn’t arrested on the spot.