2

“LIFTOFF; THE CLOCK IS RUNNING”

The Soviet Union was our rival in space. While we were blowing up rockets, they were impacting the Moon with a probe. They even photographed the far side. Each Russian breakthrough came as a shock. (Our “intelligence” on the Russian space program was pretty hot stuff—notebooks with newspaper and trade journal clips pasted in them. The military apparently didn’t feel that the civilians in NASA had a need to know whatever it was they knew.)

Most Americans followed the selection and training and further adventures of the seven original astronauts. That was about all they really knew about our infant manned space program. The astronauts were instant celebrities, not so much selected as anointed. The public, as well as the Mission Control team, was caught up in the beauty pageant aspect of the first manned launch: Which astronaut would be first? Who was the best?

April 1961

In April, as we were deploying for a pair of missions, the Russians beat us again. Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space, and in orbit to boot, and we neophytes in the Space Task Group viewed the Russian success with both frustration and admiration. We packed up our bags, kissed the wife and kids goodbye, and, a few hours later, were once again at Mercury Control. Marta was now expecting our third child. We were launching increasingly complex missions from the Cape every month. Over half of the year we were TDY, on temporary duty, at the Cape. Unlike the later years in Houston, our wives did not know each other and often lived pretty far apart, so it was a lonely time for them. Compounding the problem was the dispersal of so many of our people to far-flung remote sites. Working in Mercury Control, I was fortunate: I could easily stay in touch by phone—and I could share with Marta the excitement and pride that we felt as the program went forward.

Following two successful Redstone launches, we moved on to the unmanned Atlas mission, which was designed to test the spacecraft and the global network. The mission that would follow was the one we had been waiting for. It was planned to launch the first American into space.

After we arrived at the Cape, we found that the military, which actually ran the Cape and nearby Patrick AFB, as well as the recovery forces, had pulled the plug on our resources and reallocated them to deal with one of the worst crises of the Cold War. A force of 1,300 Cuban exiles, who had been trained and armed by the CIA and given decidedly insufficient American tactical support, had landed at the Bay of Pigs in Fidel Castro’s Cuba in the predawn hours of April 17. Initially planned under the Eisenhower administration, this ill-advised invasion had probably been doomed from the outset, but its fate was sealed when President Kennedy, only a few months into his term and ambivalent about the entire operation, withheld American air support. Castro’s small air force decimated the exiles bent on his overthrow. All this was happening a few hundred miles to the south of the Cape. We sat in our hotel rooms, anxiously waiting to recover the resources we needed for the next two missions, our eyes glued to the television sets.

The combination of Gagarin’s flight and the U.S. humiliation at the Bay of Pigs provided a sobering background to our deployment. The press focused on America’s pitiful space record, while touting Russia’s successes. It was reminiscent of what had happened a year earlier, when Newsweek lowered the boom on the Mercury program: “To lose to the Russians all we needed to do was start late, downgrade Russian feats, fragment authority, pinch pennies, think small, and shirk decisions.” I don’t recall anyone disagreeing with that assessment. The message was understood in Washington, and it was taken to heart at the Cape.

I find it difficult today to convey the intense frustration and near despair as we picked ourselves up after each setback, determined to break the jinx on the program. Now we were going for two back-to-back missions—launching an unmanned Atlas downrange and then carrying out our first manned Redstone mission. We tried not to think about the gaps in knowledge, experience, and technology in our program—they were big enough to drive a truck through—and we could never forget that while we were screwing around with baby steps in suborbital missions the Russians had put a man in orbit. So we would continue with our preparations at the Cape, tired of being one step behind. It seemed like no matter what we did, the Russians were always one step ahead.

In those dark days our only thought was, “This time it has to work.”

Testing went smoothly once we regained the test range and network resources. The Mercury network, operational less than a month when we deployed, was working beautifully. NASA, playing catch-up with the Russians, changed the Mercury-Atlas launch (MA-3) from a ballistic mission to an orbital one. We split the Canary Islands team and sent a small group to Nigeria and Zanzibar. We planned two launches in the next ten days: an unmanned Atlas orbital mission and America’s first manned mission on a Redstone.

The simulation team was composed of another small group of controllers. Their task was to create what we now call virtual reality—to replicate, in chillingly convincing detail, every element of the mission, from countdown to completion. The simulation supervisor (SimSup) had five people playing the roles of thirty. They would supply a data stream—telemetry, command, radar tracking, voice reports—and our controllers would have to respond. SimSup’s team would provide the voice calls and responses of the three test conductors, range safety officer, recovery team, and everyone else involved in a launch. One guy might play a dozen different people responding to controllers’ calls. The SimSup’s objective was to test the judgment of each individual and the competence of the total mission team. How quickly would they recognize and solve problems? How well did the mission rules and the procedures used in the various facilities and the network function in real time? Were we ready?

SimSup would prepare and send out magnetic tapes to each of the Mercury facilities. For instance, a single orbit takes ninety minutes. The tapes would be played in sequence, starting at the Mercury Control Center at the Cape. At four minutes after simulated launch, Bermuda would start playing their tape—so for about six minutes MCC and Bermuda could compare data—then MCC would lose data and a few minutes after that the Bermuda tape would end. There would be an eight-minute gap before the tape at the Canary Islands site would start running. Each of the tapes had to contain timing and data replicating what was expected to happen during the actual flight. The simulation team would introduce various malfunctions on the tapes sent out to each site and the controllers there would have to deal with them.

While all this was going on, an astronaut sitting in the capsule simulator had to deal with the same malfunctions thrown at the controllers at the various sites. If either the astronaut or the site controllers wanted to take an action that conflicted with the data on the tape, then the whole simulation would start to fall apart.

Few of the early simulations achieved their objectives. Everything was new and untested—new equipment, new procedures. Attempts to conduct “seconds critical” training often failed. Our final MA-3 training run was no exception. Our novices stumbled from the start, when the wrong tapes were selected. After several restarts, tempers flared as controllers at the separate sites began improvising in an attempt to complete the test. Later in the afternoon, a disgusted Kraft called off the exercise and told me to sort out what had happened.

Three days before the Atlas orbital test launch, I prepared the Teletype daily advisory, critiquing the previous day’s run and offering an apology. The message to all the tracking sites was blunt:

TODAY’S OPERATION WAS A COMEDOWN AND INDICATES WE STILL HAVE PROBLEMS. MISSION CONTROL’S PERFORMANCE WAS SUBSTANDARD. WE APOLOGIZE FOR THE WAY WE CLOSED DOWN THE VOICE NETWORK. OUR DISCOURAGEMENT WITH THE DRILL LED US TO WALK AWAY UNCOMPLETED.

LAUNCH FORECAST—NO DELAYS ANTICIPATED. BOOSTER, CAPSULE AND RECOVERY GO. FLIGHT CONTROL IS GO ASSUMING ADEQUATE TRAINING.

It was customary to add the latest news headlines, which included these:

U.S. WILL ACT AGAINST CUBA TO GUARD ITS SECURITY.

KENNEDY’S ANTI-CASTRO INVASION STAMPED OUT.

REPORTS CLAIM CASTRO SUFFERING FROM MENTAL COLLAPSE.

MARILYN MONROE SAYS NO TO REMARRIAGE TO JOE DIMAGGIO.

ALLISON AND MANTLE HIT THREE HOME RUNS.

AT&T 126-¼, DOWN 3/8 BECAUSE OF PROJECT MERCURY SLIP.

We could only hope now that our training would prove sufficient. It was time to launch.

April 25, 1961, Mercury-Atlas 3

The Atlas rocket, shedding ice formed by condensation on the sides of the liquid oxygen tanks, lurched skyward on three shafts of liquid fire, steam billowing from the flame bucket that channeled the fiery exhaust away from the blockhouse, support tower, cables, and pad. Inside the control room, I could not hear the engines roar, but the sense of my first Atlas launch seeped from my fingertips as I scribbled the liftoff time in the Teletype message and handed it to a waiting runner.

Without pausing, I picked up the running Teletype dialogue over the order wire, advising Bermuda of the launch time and status. Seconds after the launch, a note of anxiety crept into the Welsh accent of Tec Roberts, the flight dynamics officer (FIDO) responsible for launch and orbital trajectory control, as he reported, “Flight, negative roll-and-pitch program.”

A collective shudder went through everyone in the control room as the controllers absorbed the chilling significance of Roberts’s terse report. The roll-and-pitch program normally changed the initial vertical trajectory of the launch into a more horizontal one that would take the Atlas out over the Atlantic. This Atlas was still inexplicably flying straight up, threatening the Cape and the surrounding communities. The worst-case scenario would be for it to pitch back toward land or explode. The higher it flew before it exploded, the wider the “footprint” of debris scattered all over the Cape and surrounding area would be.

The RSO (range safety officer) monitoring the launch confirmed the lack of a roll-and-pitch program, then continued to give the Atlas an opportunity to recover and start its track across the Atlantic. The RSO lifted the cover on the command button and watched as the Atlas raced to a fatal convergence with the limits on his plot board.

At forty-three seconds after liftoff, Roberts reported, “The range safety officer has transmitted the destruct command.” Seconds later, Kraft’s TV glowed a vivid black and white with the explosion. (We did not have color monitors.) We waited, not speaking, counting the seconds, listening for the telltale, muffled krump that would signal the mission was over. Carl Huss, the retro controller (RETRO), responsible for reentry trajectory planning and operations, reported, “Radar tracking multiple targets.” Roberts’s response echoed all our feelings: “Chris, I’m sorry.”

We sat by the consoles, not talking for several seconds. Then, one by one, the controllers closed their countdown books and started to pack their documents.

My message to the remote site teams was succinct: “MA-3 WAS TERMINATED BY RANGE SAFETY AT 43 SECONDS INTO FLIGHT. STAND BY FOR DEBRIEFING.”

The destruction of the Mercury-Atlas 3 left us dazed and disheartened. We had gone to launch feeling that with three successful unmanned suborbital missions the jinx seemed broken, the odds were turning in our favor. Then the Atlas had to be blown up.

There was no cheer as the Mercury team retired to the bar at the Holiday Inn in Cocoa Beach and waited for Walt Williams, the operations director, and the launch team to finish the press conference. We knew they would take a beating. We had no time to lick our wounds or feel sorry for ourselves and no one had much to say. Numb with shock, frustration, and anger, we were uncertain about the impact of this spectacular failure on the entire program. We did know that it would mean more time at the Cape, more time away from our families. But did we really know what the hell we were doing? The Atlas was the key to orbital flight and we had racked up two Atlas failures in three Atlas missions.

When we debriefed and vented our frustration over drinks at the bar, it was all in the family. During the missions, Kraft set the tone when we lost our composure. He knew that he could not show any uncertainty to his team. In Mercury Control there was no room for displays of emotion. Kraft allowed himself an occasional broad smile and lit up a cigar when his gang did well. When we failed, maybe he would mutter a curse word or two. His message from the earliest Mercury days: we were the visible point men for the program and we had to maintain a calm, professional, and confident image. But, as long as no outsiders, especially press, were around, we could let it hang out when we left the Cape and hit the bar.

We didn’t even have the luxury of a day off. We debriefed, wrote our reports, and, on April 26, 1961, returned to Mercury Control. With only seven days to prepare for our first manned flight, our self-confidence was badly shaken and we all shared the same unspoken fear: in only a few days, would we be crowning our first space hero—or picking up pieces of him all along the Eastern seaboard? We attacked the final days of the training schedule with a renewed urgency. Everyone connected with the program was now consumed with one goal: the successful flight of America’s first man in space. We simply could not accept, or even contemplate, another failure.

It was the top layer of NASA management which was directly in the line of fire coming from Congress and the executive branch. Our new administrator, James Webb, who was everybody’s boss, didn’t exactly deflect criticism when he said, “This present program is not designed to match what the Russians may do.” Reporting to him for manned space flight were Wernher von Braun at Marshall Space Flight Center, Harry Goett at Goddard Space Flight Center, and Robert Gilruth at the Langley Research Center. (Mercury preflight operations at the Cape were run by a division headed by G. Merritt Preston and reported to Gilruth.)

Gilruth, director of Project Mercury and boss of the Space Task Group, was the pioneer who focused the Mercury effort. He was regarded with great affection by those who worked under him. Starting at Langley in 1937, he had a sterling record of achievement in flight-testing. By the late 1950s his people were the most knowledgeable on high-speed flight research and he was the obvious choice to form and lead the Space Task Group.

Gilruth’s Washington counterpart was George Low, an Austrian whose family fled to America when Germany invaded and occupied his native land. After serving in the Army in World War II, he worked for Convair and then was chief of special projects at the National Advisory Committe for Aeronautics—NACA—the predecessor of NASA. In the summer of 1958 Low was tasked to organize a new space agency and became the chief of manned space flight during the agency’s early years. He was absolutely determined to put a man on the Moon, believing only such a bold goal would sustain the manned space effort. Personally, I would settle for rockets that worked.

In the first two years, we spent almost half our time on temporary duty at the Cape. When we left our homes and families behind, we never knew whether to pack for a few hours or a month. We lived out of our suitcases, in nondescript motels, coping with loneliness, too little perdiem, and too many failed countdowns. Invariably we would go home to find our wives feeling neglected and frustrated. You have no doubt heard the saying “Behind every great man is a woman”—and behind her is the plumber, the electrician, the Maytag repairman, and one or more sick kids. And the car needs to go into the shop.

To make matters worse, most of the wives had a postcard image of sun-washed beaches and a kind of intergalactic glamour. We felt this pressure and knew we could not resolve it. The beach was only a rumor to most of us, and glamour was a tub of beer on ice. The Cape Canaveral area was hardly the glossy Florida of Miami or Fort Lauderdale, but it was a community full of solid, decent working people, who encouraged us by their support for our fledgling space program.

We didn’t have nine-to-five jobs. Pad tests, simulations, and practice countdowns are driven by launch pad activity. Launch preparation is more an art than a science, with the high priests (test conductors) of the blockhouse, in charge of the countdown, dictating the overall schedule. Our job at the Mission Control Center was to be ready whenever the launch team needed us. The MCC support for the capsule and booster launch pad tests usually started with the test conductors’ call to console stations about 2 A.M., so the controllers usually hit the sack about sundown and arrived at Mercury Control about 1 A.M. to prepare for the test.

The flight rules that were a mystery in the beginning now anchored me at the center of the mission policy and decision process. They were an upscale equivalent of the Go NoGo criteria we used in aircraft flight tests. I had inherited the rule-recording job when Kraft sent me to the Cape for the first Mercury-Redstone test. This task opened the door for me to every technical aspect of Mercury operations. In the early months, I was the scribe sitting in on Kraft’s meetings with crews, controllers, and management. I wrote out the record of the decisions of the meetings, putting them in the flight rule format, defining each decision as a series of conditions followed by the action procedure.

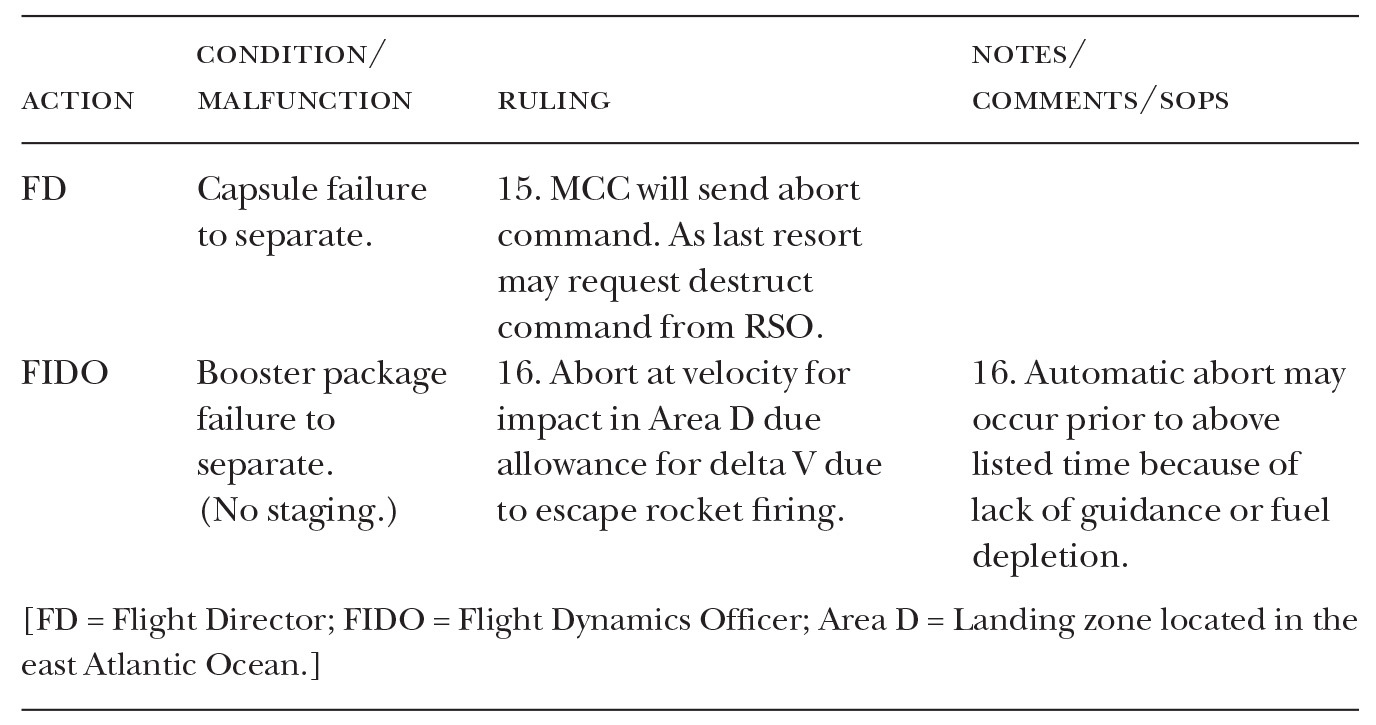

The Mercury rules summary was thirty pages long. Many of the rules were procedural in nature and placed a heavy weight on the judgment of the controllers. Go or NoGo conditions were underlined in vivid green or red. The value of compiling and defining rules was not in the document itself as much as it was in hashing out Go NoGo stipulations in team meetings. The rules were set up on each page in this fashion:

Frequently, Kraft would leave a team meeting disagreeing with the results. The controllers and doctors were too conservative for his way of thinking. After reflecting for a while, Kraft would say, “I didn’t like their input. When you write the rules, let’s do it this way.” Many of the critical flight policies were determined over dinner at Ramon’s restaurant, late at night in one of the bull sessions, or during a lull after a tough training run.

No matter what the rules said, the ultimate authority was the operations director, Walt Williams. Born in New Orleans and an LSU graduate, Williams worked for Martin Aircraft and then at Langley, where he concentrated on control and stability systems during World War II. In 1956 he was head of engineering for the X-1 project (our first aircraft to break the sound barrier). He went on to be the director of virtually every supersonic test program for jet-and rocket-propelled aircraft and by 1958 was head of the X-15 test committee. He had been assigned as Gilruth’s deputy for Project Mercury, and was the feared but highly respected boss of every aspect of Mercury operations.

The days remaining before the manned launch passed rapidly. Walt Williams gave the operation’s Go at the mission review on launch minus one day, May 1, 1961, and the capsule servicing began as we conducted our final simulations. We did our data checks and returned to the motel. Normally, I sleep like a dead man, but I tossed and turned most of the night.

Since I had spent most of my time with the team at the Cape in unmanned rocket testing, most of what I knew about the astronauts came from the newspapers. When I did see them, they seemed to live in a world apart from the rest of us, communicating only with the top managers and spending most of their time in hands-on training, learning all they could about their spacecraft and rockets. I didn’t blame them. The early space hardware had much in common with the imaginary technology in a Jules Verne science fiction novel. The capsule used steam-powered thrusters for control (the steam being generated by the reaction between hydrogen peroxide and a catalyst in a nickel chamber attached to the thrusters), a periscope for visual tracking, and an electric Earth globe for determining position. Half of the systems were primitive by today’s standards for aircraft avionics and control systems, while the other half were untested first-of-its-kind technology.

Their test pilot backgrounds made the Mercury Seven highly independent—and fiercely competitive. Each one of them was determined to be the first man in space; each believed his performance during the months of training and testing would win him the coveted prize. As launch time neared, Gilruth took the extraordinary step of asking each astronaut to rank all the others in the order of who was best qualified for the mission. Some thought he did this just to confirm his personal selection. Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, and John Glenn were chosen from the seven; one of that trio would be the first among equals. Shortly thereafter Life magazine got into the act, dubbing the first three the Gold Team, the remainder the Red Team.

The brass felt a need to reassure the public there was no split in the ranks. Wally Schirra, Deke Slayton, Gordon Cooper, and Scott Carpenter stepped forward at a press conference a few days later to confirm that there was plenty to do and they all were still on one team, not divided into “red” or “gold” factions. Their reassuring words and smiles could not cover up the fact that someone else had indeed been chosen to be first. NASA did its best to soothe the egos of those who did not make the first cut. The lyrics to the music went like this: Each astronaut had an important role to play. There were plenty of flights for all. And, sure as hell, there was enough work to go around.

We in MCC were not surprised by the choice of Glenn, Grissom, and Shepard to make the initial flights. The controllers had worked briefly with all three, but only our bosses and the astronauts knew who would fly this very first mission. Since we had seen more of Shepard, we were betting on Al. The media seemed to favor Glenn. In part it was his image as a God-fearing, clean-cut American patriot and good family man. But journalists may have reported this in hopes of provoking someone into saying who it would be.

Shorty Powers, a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force, was the man in charge of public relations and the “voice of Mercury Control.” To Shorty, dealing with the press was just like a game of poker: never let on what is in your hand—and try to bluff them into showing you theirs.

Like Williams, Shorty never seemed to sleep and his exhausting work schedule only compounded his irritability; it took very little provocation to make him lose his temper. When he did, it was like a launch, a great deal of energy and noise expended amid the fire and smoke. He was a bantam cock of a guy, about five-foot-four or-five, always dapper and a bit of a strutter. For the most part, Powers had an unenviable job, setting up a public relations barrier behind which the engineers and the astronauts could work in peace, while at the same time trying to feed reporters’ insatiable demands for information. He really needed two sets of astronauts, one to do the mission, the other to perform for the media.

The astronauts and controllers stayed at the Holiday Inn at Cocoa Beach. It was not unusual to see Walt Williams charging into the bar late at night to get an answer to a problem from one of the controllers or engineers. He was likely to find the man he wanted there, because all of us sat around and chewed over rules and procedures endlessly and tuned in on Williams’s questioning to get the latest word.

We knew that three days prior to the launch the selected astronaut would check out of the Holiday Inn and quietly try to move out to the crew quarters at the Cape. Reporters hung around the Holiday Inn fishing for information, striking up a conversation, occasionally trying to pass as a member of the launch team. The press, which had become somewhat negative and adversarial after the Gagarin flight and the Atlas 3 failure, was now caught up in the excitement of this new chapter. Realizing that a man’s life and the future of the program were at stake, their coverage finally began to capture the excitement and suspense surrounding the imminent mission. The control team, taking our lead from Powers, neither confirmed nor denied any of the press speculation and ignored all the rumors that buzzed around the program like a swarm of busy bees.

The weather was stormy at midnight on May 2, 1961, when the control team arrived to support the initial check-out. The countdown progressed through the fueling of the Redstone while the launch team held the transfer van (used to move the suited astronaut from the hangar to the launch pad) at the hangar until the weather improved, or the launch was scrubbed

We had adopted the call sign “Freedom 7” during our final training runs, but I never knew who had named the capsule. Just one week after the Mercury-Atlas 3 failure we were once again in Mercury Control counting down to launch for our first manned mission. The headlines read: “AS HOP NEARS ASTRONAUT X IN SECLUSION.” Soon the world would find out—and so would we. I think only Kraft, Willams, and the flight surgeon knew it was Shepard. It had been decided in Washington that the identity of the first man would remain a secret until he stepped forward to climb atop the rocket.

The Russians did not announce any launch in advance; in fact they didn’t release any news about their manned spacecraft effort until they were good and ready, and even then they gave only carefully selected details about a flight. They could do this quite easily in a closed society in which news was strictly controlled by the government. We did not have this luxury. From its earliest days, NASA had followed a policy of maximum, though prudent, disclosure. We had to do everything openly—and soon under intensive, live TV coverage. In their own good time, the Soviets had announced that Gagarin spent 108 minutes in orbit before returning safely to Earth in a parachute-cushioned landing.

We wanted to catch up and we believed that, at last, we were ready to do it—at least for the first step, a suborbital mission of limited duration. Dressed in his silvery space suit, Alan Shepard stood behind the door of Hangar S. Outside, the van that would deliver him to the launch site waited, along with a large group of reporters and photographers who were eager to tell the world which astronaut would step through the door.

Lightning and rain had been playing about the Cape all morning, and when the clouds had not cleared by 7:25 A.M. local time, the flight was canceled. No one could be responsible for the weather, but it struck us as another in an unending series of tough breaks. Who would stop the rain?

Shepard shimmied out of his suit and downed a shot of brandy. An alert reporter standing by the hangar door had seen him and broke the story: “FIRST U.S. ATTEMPT TO PUT MAN IN SPACE POSTPONED 48 HOURS. SHEPARD GIVEN FIRST CALL FOR HISTORIC VENTURE.” The secret was out. Hard-charging Al Shepard was at the head of the line.

We drowned our disappointment in the usual way—with a mission scrub party. No matter what hour the test was scrubbed, we would return to the motel wide awake, after the lounges had closed, or before they opened. We had stashed beer and snacks at the Holiday Inn, which often donated food left over from the previous day’s menu. We would eat and drink, and talk about what had gone wrong. It was a little like throwing a rueful party after a nonbirth; at least we hadn’t experienced another disaster, and the baby was still there in the womb, ready to go. All we could do was pace the floor and wait.

In the heat of the following day, some of us headed to the ocean or the pool, or played full-contact volleyball, to sweat off the beer we had tossed down. The chalked volleyball sidelines didn’t last long and there was the usual quibbling on out-of-bounds calls. The solution was to dig a trench and mark the sidelines with gravel embedded in concrete. Out-of-bounds calls were a lot easier when you came up with bloody forearms after a diving save. Bruises, sprains, jammed fingers, and nasty cuts were the order of the day.

Kraft, a standout baseball catcher and center fielder in college, was a fierce competitor. But on the volleyball court he was no longer the boss, just one of the team members. Carl Huss, the MCC RETRO, was a burly five-foot-eleven guy with black bushy eyebrows and hair. When playing volleyball he had a habit of rising on his toes and shifting from left to right with a rolling motion. His menacing visage, combined with this motion and his perpetual growl, earned him the nickname “Dancing Bear.”

During one match, Huss spiked a shot straight into Kraft’s face; the ball drove the prongs of his sunglasses deep into the flesh of his nose. Without flinching, Kraft pulled out the prongs, wiped the blood off his face, looked at Huss, and growled, “Nice shot. Try me again!”

After multiple injuries to his team members, Kraft set the rule: no volleyball after L – 3—launch minus three days. Any controller violating the rule and unable to perform his console duties would be “disciplined.” No one was willing to find out exactly what kind or degree of discipline Kraft meant.

The beverage of choice after these matches was Swan Lager, an Australian beer, and our supplier was Jack Dowling, the Australian government’s envoy to NASA. Jack was the picture of a typical Aussie. He was a bit older than most of us, stocky, with wavy black hair, flecks of gray in his mustache, and eyebrows like caterpillars. All he needed to complete the image was the Crocodile Dundee bush hat. He had the accent, the one you never missed when you called “Goddard voice” and the switchboard operator patched the voice communications to the Australian tracking stations. You had to be careful about confusing their language with the one we were developing for space.

When we had needed a tracking station in the Southern Hemisphere, the people Down Under were quick to respond. They have always been our stout allies, and their very isolation inspired them to sign up for any new adventure. They sent their volunteers to train with us, and Dowling was one of those who learned to love the States so much he never left.

The personal relationships that developed in the early years at Cape Canaveral provided the foundation of a brotherhood that extended through Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. This bonding got us through the difficult times. We worked together, played together, and lived together.

If I close my eyes I can recall images of that strip of coastal Florida—a line of motels, restaurants, and bars (some pretty funky) lining the highway that ran south from Daytona Beach through Titusville and Cocoa, where a causeway across the Indian and Banana rivers took you to the small town of Cocoa Beach. It was a two-lane blacktop that shimmered in the hot sun and paralleled the swamp that stood between the Cape and the mainland. Although Orlando was only a short drive inland, it might as well have been on Mars. Our world was confined to a small, tight circle centered on those strange new structures—gantries and launch pads and telemetry antennas—sprouting up on an overgrown sandbar. NASA’s arrival in this once calm and sleepy area would change it forever—and make it perhaps a greater tourist attraction than the locals ever dreamed it could be (and perhaps more than many wanted it to be).

In this setting our bonding produced a spirit that responded to the challenge of John Kennedy’s inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.”

This was the spirit that a few days later would bring space and the astronauts to the front pages of newspapers and into the homes and hearts of America.

May 5, 1961, Mercury-Redstone 3

When the launch was scrubbed on May 2, it was reset for May 4—and then scrubbed again because of weather. But then the weatherman gave us a solid Go for the next day. The weather was windy but clearing when Huss and I left the motel shortly after midnight. As we left, I drove around the east end of the motel to see if the searchlights at the launch pad were on. If we saw the lights, we would know that the launch complex was active and the countdown progressing. The lights drew me like a magnet; when I saw them I picked up speed, and to hell with the local cops. Our sleepiness quickly vanished during the twenty-minute drive.

Highway A1A took you through the heart of Cocoa Beach. With only a single stoplight, it was a small town in the process of trying to grow and live with its newfound fame. The brilliant, garish neon of the motels and restaurants and go-go bars seemed more like Las Vegas, but they were soon behind us. The traffic was heavy, as it usually was, cars pulling out of motels and dark streets to join you as you passed by. You drove into an inky darkness after passing Fat Boy’s restaurant, which marked the city limits of Cocoa Beach. This traffic was different from the usual relaxed pace of tourists and locals. From this point the cars on the road were moving swiftly, their drivers knowing exactly where they were headed—a personal rendezvous with history.

The interior of the space capsule that Alan Shepard would soon climb into was so small that a human being could barely fit. The back of his couch was within inches of the heat shield. The instrument panel was less than two feet from his face and the parachutes only five feet forward. John Glenn had hung a sign on the panel: “No Handball Playing in This Area.”

The Redstone rocket would lift Shepard’s two-ton capsule on a fifteen-minute foray into space. He would reach an altitude of 100 miles, experience five minutes of weightlessness followed by a crushing 11-G entry, and land 260 miles downrange from the launch pad.

Closing in on the Cape, I could see that the lights looked much like the lights of the small cities amid swamplands when I trained and flew in Georgia. After a brief stop for a badge check, we continued toward Mercury Control, passing the security roadblocks that are always erected as launch time nears.

Huss was not a man given to making small talk. Like a bear coming out of hibernation, he would wake up slowly, so we didn’t talk to each other. I enjoyed the silence, which allowed me to think about what lay ahead as I made the long swooping turn to the north and the searchlights. The stars were occasionally visible through the muggy haze of the Cape. The outline of the launch tower was not yet visible through the palmetto as we approached Mercury Control. After parking the car, I started to psych myself up, just as I did when I was flying. In my mind, I could hear the marches of John Philip Sousa and the cadence quickened my step.

The support team finished its systems checks and I sat down to check out the communications at my console. There had been no countdown delays and the capsule test conductor (the team leader for the capsule check-out) came on and reported, “The count is on schedule.” I then moved to Kraft’s console to check communications from his voice panel to the pad team. On this day, I was covering his tail, watching for problems while Chris went about the business of being the flight director. A half hour later, he arrived, dressed nattily as usual, regardless of the time of day. He made his standard comment: “How’s it going, young man?” I gave him a thumbs-up. He reached in the drawer for his headset, adjusted it, and then sat down.

At his console, Kraft projected the image of a general reviewing his forces prior to battle. The only time he showed any uncertainty was when the IBM engineers, Ira Saxe and Al Layton, periodically reported on the results of the network data flow testing. Tec Roberts and Carl Huss were monitoring the flow of data coming in from the tracking stations to Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, which in turn came down, via dedicated telephone lines, to the data display on the four plot boards in front of them. Saxe and Layton were concerned that there was a lot of ambient noise on the data lines and, like the rest of us, were not sure how a burst of static might affect the two computers at Goddard.

Saxe and Layton retested the lines and announced, “We had 270 failures out of the last 11,250 transmissions.” The perplexed expression on Kraft’s face indicated his annoyance. Softly, he asked Saxe, “Dammit, will you please tell me if that is okay?” That was the one thing they could not do. Getting a less than satisfactory answer, Kraft frowned, pretending to make sense of their report. Nobody knew how much bad data the computers could digest and still come up with acceptable answers. Computers just seemed to work, crash, or go off on tangents for no reason, with Huss and Roberts at their mercy.

Shepard had awakened at 1:00 A.M. and, after breakfast with John Glenn and Dr. Bill Douglas, began to undergo his physical exam, sensoring, and suiting. The weather was definitely better than the day before and a feeling of bullishness pervaded the control room. More controllers arrived and began making their checks.

Walt Williams, rumpled as usual, showed up about 2:00 A.M., after a quick, how-goes-it conversation with Shepard and Glenn. Chain-smoking, Walt talked briefly with Shorty Powers, then moved to his desk behind Kraft, his voice hoarse, grunting a question to Kraft. (Another sign of the times was that most people smoked in those days—and smoked a lot. Mercury Control would have been a nightmare for those who object to secondhand smoke because the air was regularly blue with tobacco haze.) Chris gave Walt a high sign, happy about the weather forecast.

The report that Shepard had entered the transfer van and was en route to the capsule gave me a chill. I passed the report to the controllers on the two tracking ships in the Atlantic about 280 miles down-range, north of Grand Bahama Island. When the van arrived at the pad, we saw a flurry around the base of the Redstone. It was surreal. The brilliant floodlights turned the night to day. The silver-suited Shepard paused, looked up, and then strode to the gantry for his sixty-five-foot elevator ride up to the capsule. I noted in the log that Shepard entered the capsule at 5:20 A.M. Again, I felt a shiver. This was history. I hoped that the other controllers were doing a better job of keeping their minds on their work than I was at that instant.

The countdown continued sporadically with five holds. During one of them I got Kraft his customary pint of milk to calm his ulcer. Williams spent more time outside checking on the weather, which was becoming increasingly overcast. With the launch gantry removed, the Redstone rocket stood starkly silent and alone on its platform.

It was now a little before seven o’clock in the morning. Looking up at the countdown clock I thought, If there ever was a time and place to get it all together it was now. It was time to kick in the afterburners and regain our confidence as Americans and as leaders.

Williams called a weather hold at launch minus fifteen minutes. Shortly thereafter, a problem developed in a Redstone power supply, and the decision was made to roll back the gantry and recycle the countdown to thirty-five minutes and hold. I got up to get a cup of coffee and stretch. Nerves were taut. It wasn’t a subject anyone talked about openly, but we in MCC fully expected to lose one or two astronauts in Mercury. The prayer at that moment was, “Not now, Lord, please, not today.”

Pilots don’t growl at their crew chiefs, so it came as a surprise when Shepard, in Freedom 7, the tiny Mercury capsule atop the Redstone rocket, growled at his ground crew, “Why don’t you guys fix your problems and light this candle?”

The countdown had been holding for weather when our computer at Goddard crashed, requiring a complete check run. This was our third attempt to launch MR-3 and the pressure from Washington was mounting.

Goddard estimated a delay of ten minutes for the computer check. Kraft, sensing the tension that had built up in the control room over the delay, told his keyed-up team to “take five and get a cup of coffee.”

When I returned from my coffee break I lit another cigarette, and as the test conductors completed the recycle and announced the hold, the air-ground loop to the capsule came alive. To my astonishment, I heard the then popular comedian Bill Dana’s high-pitched parody of a reluctant astronaut:

“My name . . . José Jimenez . . . Do you know what it really takes to be an astronaut?”

“No, José. Tell me.”

“You should have courage and the right blood pressure and four legs.”

“Why four legs, José?”

“Because they really wanted to send a dog, but they decided that would be too cruel.”

As the José Jimenez routine continued, I punched the loops on my intercom to see if the recording was coming from Mercury Control. “Dammit,” I thought, “who the hell is playing a nightclub act on the countdown loops?” I sure hoped it was not coming from Mercury Control. If it was, I knew I would catch hell from both Kraft and Williams. I expelled a sigh of relief when it became clear that the comedy routine was being piped in from the blockhouse. A wonderful discovery: our German colleagues had a sense of humor. But was now the time to display it? It would be a distraction for the launch and flight team—and if the mission had been scrubbed, the bosses would have been on the warpath. As it turned out, however, Gordo Cooper and Bill Douglas, the surgeon, had conspired to patch Dana’s recording of José Jimenez into the capsule. They felt Shepard needed to relax a bit during the hold. This informality added a degree of unreality to the fact that we were only minutes away from launching the first American into space.

Not everybody was amused; I could see that Kraft was not happy. He did not like surprises that would distract his team. But by now the countdown was forgotten momentarily. The controllers were drinking coffee, joking and enjoying Bill Dana’s comic monologue. Dana had been dubbed the Eighth Astronaut by Shepard and Schirra and was a favorite of everyone working on Mercury. Later, in the bar after the launch, I would decide that this bit of humor was exactly what we needed to relax a bit and get loose and ready for launch. But I am damn sure the Russians wouldn’t have tolerated such shenanigans.

Shepard had been in the capsule for more than four hours when the count again resumed. It went smoothly and, after a brief hold at two minutes, continued toward liftoff. During the last seconds I saw Kraft’s hand move to the liftoff switch on his console. I just hoped he didn’t throw it early and start the mission clocks. At T-equals-zero, I glanced at Kraft’s TV, saw the rocket ignition, and then heard Shepard say, “Ahhh, Roger, liftoff and the clock is started.”

I logged the liftoff time (9:34 Eastern Standard Time) as 1434Z (Z for Zulu, or Greenwich mean, time, used to establish a standard time for all the tracking stations scattered throughout different time zones) in the Teletype message, turned in my chair, and took off to the Teletype center. Oops. I had not removed my headset. After I’d run about fifteen feet, the headset cord stretched to the maximum, snagged a chair, and sent it tumbling to the floor. Kraft, distracted, looked in my direction, frowned, then returned to the business of launching the first American into space.

Sheepishly, I picked up the chair and returned to the console as Shepard made his thirty-second status report. Shorty Powers announced to the world that “everything is A-OK,” a phrase hated by the controllers and crews as “too Hollywood,” but one that soon became a part of the American vocabulary. It seems quaint now, all these years later, virtually unused, almost forgotten.

The two previous Redstone missions taught me that a ballistic mission is over in a flash. An energy-charged 142-second rocket launch followed by a five-minute weightless period, retrofire, and then a reentry. The drive from the hotel to Mercury Control was longer than the fifteen-minute flight time. Shepard’s mission was just like my first jet solo, a blur of noise and motion, an event long anticipated that was over far too soon.

Indeed things were A-OK. After over four hours in the capsule, Shepard was in peak form reporting launch events. At liftoff his heart rate had briefly increased to 120, peaking five minutes later at 140 beats per minute as Shepard called, “Booster cutoff.” Now weightless and traveling one mile per second, Al was in the test pilot’s nirvana. I was damn happy that the mission was going well and that Al’s performance would answer the medical scientists’ concerns about whether man could function in space. I had always felt that the flight surgeons were too plodding, too conservative for the rapidly evolving program.

After capsule separation from the booster the automatic system turned the capsule into a heat-shield-forward position. Approaching the 116-mile-high apogee (the highest altitude on the trajectory), Shepard took over manual capsule attitude control, maneuvering in the roll, yaw, and pitch axes and reporting that the capsule responded much as the simulators had. Using the periscope he reported seeing the western coast of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico.

Only moments later, Carl Huss broke into the communications loops, beginning the countdown to retro sequence. His words hung briefly, then were echoed by the MCC CapCom, “5 . . .4 . . . 3 . . . 2 . . . 1 . . . Retro sequence!” Shepard confirmed he had maneuvered the capsule to attitude for rocket firing.

The weeks of frustration and training were finally paying off in a perfect mission. Now all we needed were the parachutes.

I listened, amazed at the professionalism that had developed in the Mercury team in the six months since I had joined. The pad team, Mercury Control, and the recovery forces were working in perfect synchronization, with an almost casual tone in their voices as if they had done this many times before. In less than fifteen minutes our first manned mission was over.

Shepard was safely aboard the aircraft carrier Lake Champlain eleven minutes after landing. While dictating his pilot’s report on the carrier Shepard was called to the carrier’s flag bridge to answer an unexpected telephone call. President Kennedy had watched the launch and landing closely via television and was now one of the first to congratulate America’s new space hero. Kraft rapidly wrote out his mission summary report. It was less than two pages in length. It was now time to celebrate.