The Squid Is My Brother

Dear Mother,

Got in my first fight at school today. Wasn’t my fault.

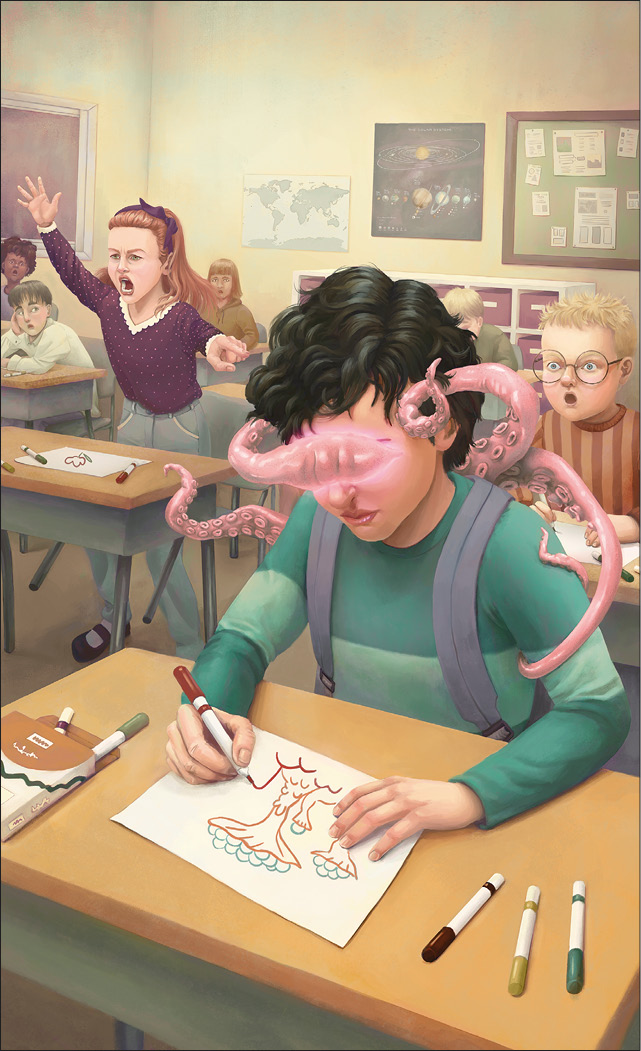

Happened in art class. Was instructed how to “draw”—am familiar, not infant. Was given “wildflower.” Asked teacher if I could draw something from home biome instead. Raised hand, obtained permission, just like in the vids. (Would have made you proud.) Teacher accepted, said something about “cultural diversity.”

Then, was given supplies: markers of limited spectra. Did not object, did not argue. Only invited Brother to change my vision filters. Did not even make a sound!

Brother reached out of backpack, suctioned one true arm against my left temple, then put amorphous arm over my eyes, just like you taught me. Achieved seal, was adjusting vision when heard shriek from nearby table partner. (Perhaps should have used audio filters instead.)

Native Earth girl: “Ew!” and “Put away the monster.”

I did not understand, neither did Brother, but both felt … hard to explain. Perhaps will learn word, but new concept, never experienced until Earth, and never so strong as today.

Brother retreated, pulled closed backpack.

Put my own head down.

But native Earth girl called teacher, made chirping noises. I didn’t listen.

Teacher asked nicely that I keep Brother put away. Only, teacher doesn’t say Brother; says “Xeno-org” like a dirty word, like refuse from science experiment.

I asked why another student, short boy, gets to wear eye filters. Teacher says not to make fun of glasses. Children laughed—no, not laugh, snicker. Laugh implies joy.

Later, at the recreation break, native Earth girl approached with others. Said something I didn’t understand, then snickered again.

When I turned to walk away, she grabbed at backpack, saying, “Don’t need backpack for recess.”

Felt Brother clench to hold onto my spine, readied my muscles and pumped adrenaline. Brother would have slipped out of backpack to stay with me, but rules about Brother and backpack …

So I spun, held tight to backpack strap with one hand, hit with other hand. Not intended to damage, did not account for added strength from Brother. Not my fault little native Earth girls don’t train in variable gravity. Not my fault they weren’t taught not to touch or grab other people or their symbiotes.

Had to apologize to teacher, to principal, then to girl when she woke up, then to girl’s family. Had to keep Brother completely enclosed in backpack so they would not be offended. Had to apologize again for telling them, “Concussion builds character.” No scientific basis for that, just something you (Mother) said once to an ensign; thought it amusing.

Host family had the talk with me. Male caretaker insists he’s not mad, just disappointed. Female caretaker had to explain what that meant. Told me to write a letter to you to tell you what I’d done.

Truth: I feel bad about little girl. She didn’t know about hole in backpack, or that Brother is always connected to me. Did not feel bad about teacher, principal, or little girl’s family, even if they said something about “ambassador” and called you, “Commander Kessler,” a hero.

Miss you. Hope you are safe. Glad I have Brother. Not sure if I understand purpose of “exchange program.” Perhaps when older …

Love,

Michaela Kessler

P.S. Male caretaker read before I sent. Advised running through grammar program to “fill in sentences.”

Declined. No need for superfluous pronouns and articles when meaning is clear. Just like you taught me.

I really hope my second day of school goes better. Can’t say I like it though, and it doesn’t seem to like me. Me + Earth School = Opposite of Symbiosis. Not that any of the students here would know symbiosis if it latched onto their intestine. I wonder if it’s just “DC” schools; maybe Cape Carnival is better, sounds more fun. Will have to ask Charlie the next time we call. Charlie is older, probably has more interesting things to study, maybe with kids who are … different.

Still, I wake in the morning, Brother helps my respiration rate change for consciousness. I wash and dress, line up the hole in the back of my shirt for Brother. I eat real eggs from a species called “farm-raised”—I like the eggs, and so does Brother.

I am always careful putting on my backpack. Have to be. The hole is big enough for him, and he can squeeze through a pretty small space as is, but if he’s pinched, then I get twinges all down my left side. So I slip on the modified pack, and Brother knows to pull all his arms in.

Brother doesn’t object, but I can tell he’d rather be free or in pressure suit. Female caretaker says it’s just because it’s what I’m used to and that I’ll “adjust.”

I keep backpack on and open when riding to school. Caretakers know better, don’t object.

I keep backpack on and closed in class. Teacher knows, but sounds strange when reminding other students, as if not really believing, or not wanting to talk about Brother.

Reading class is annoying, but tolerable. Brother wants to read, upset that he can’t join me, and I’d remember better if Brother were there to help me record it. Brother misses seeing, can’t see as well in the backpack. And no, as I try to explain to caretakers, can’t see through my spine; spine doesn’t have eyes.

Brother can hear though, better than me, retains vibrations, passes little information, like passing notes in class. Tells me who is snickering, who is whispering. They wonder what happens if I take off the backpack, why I am so tall if I’m so young, whether I have special powers. Mostly, they wonder about what Brother really looks like, and they make shiver noises. Sometimes, I slowly turn to look at them and grin, because they don’t think I can hear them, like a real horror villain. Mother would probably tell me that it’s not good to do that. She would say, “Don’t encourage them.”

I don’t go out to recess anymore. Teacher lets me stay in.

During recess, I open book to show Brother the pictures. Brother climbs far enough out of backpack, finds my temple, and wraps one arm over my shoulder.

Hear teacher’s breathing change to gasping, panting. See teacher clutching at chest—immediately wonder about oxygen intake, but have to remember that Earth is a naturally oxygen-rich world, and that classroom has nonsealed exterior door—(elementary school standard, I am told.) No, teacher is having panic attack. Not medical danger.

Teacher says, “Mica!” (Never asked permission to use short name.) “Mica, put it away.” Her voice shakes, her jaw quivers.

I do not mean to cry—not a logical response, not expressing pain, calling for Mother, or purging toxins from body. Just sad. Mother would say, “No use.” (Mother would still hug.) But tears come out of tear ducts anyway, go straight down both cheeks, on account of fixed-point gravity.

Teacher’s expression changes. She approaches, begins to say my name— Then eyes widen! She stiffens and collapses.

I find this confusing. Meanwhile, Brother finishes collecting tears from my cheeks. Can use the salt and moisture. Natural reaction. Apparently terrifying to teacher.

Wonder if representative of all teachers …

“I can’t have it in my classroom,” says teacher. Doesn’t lower voice, assumes I cannot hear because separated by wall. Does not understand how attuned Neptunians are to vibrations; obviously, Brother hears.

The chair in the waiting room is deep enough that the backpack has room. My toes scrape the orange carpet as I swing my feet.

“Well, clearly, there need to be some boundaries communicated,” says principal in funny voice, harder to understand.

“No other children are allowed to bring pets into the classroom,” says teacher.

“It’s not a pet,” says a third voice I don’t place. “We’re talking about her symbiote, and she can’t just—”

“And we have to look at this like a seeing-eye dog kind of thing,” interrupts principal.

Third voice softer, understanding, “I think even that is too …”

“Look,” (Teacher) “I can’t have it in my classroom. I’m sorry. I can’t. I mean, I can’t even look at cooked squid. Switch her.”

“Well,” (Principal) “I wasn’t able to get her host family on the phone to make anything official. But let’s make some alternate arrangements today. Okay? Can you … check in with her, and …”

“Sure,” (Third Voice).

Teacher and principal exit office, opening door right in front of me. Brother is completely out of sight, but teacher won’t look at me. Principal gives a smile. Fake. They both walk away.

Third voice appears at the door, looks down at me, also smiles. Hopefully less fake.

“Mica,” he says, “do you want to come in?”

I stand, keeping one hand on my backpack strap, and walk into the office. He shuts the door behind me.

Office is … simple. Not much lighting, all drawers need keys, all cupboards have latches. The one plant is a succulent. Other than the gravity-hung pictures, kind of reminds me of home station.

“It sounds like you had a bit of a rough morning, Mica,” he says. He is large, not just tall but broad, not right shape for spacesuit. He arranges a chair that is shorter and gestures for me to sit in it.

I do not object.

“I’m sorry,” he says. “I’d like to talk with you about it, if that’s okay.”

I look around the room. I do not have anything to say yet. Brother frets from inside the backpack—I don’t know which of us is more nervous.

“My name is Mister Royce. Do you remember me?” he asks.

I nod. “You signed me up for class.”

“I did. Do you know what my job is?”

“Staff sergeant?” I guess.

He chuckles, a friendly kind of laugh. Brother relaxes. “Not exactly. I’m called a counselor, and I have two jobs: one is to register students for classes, and the other is to talk to people if they’re having a rough day.”

“Oh.”

“Now, Mica—” He pauses, changes expression. “Do you like to be called ‘Mica’?”

“Michaela,” I stammer, giving my longer name. “I don’t …” My cheeks get really warm. For a moment I worry I might cry. “Mother and friends call me Mica.”

“Oh, thank you for letting me know, Michaela. Is there anyone else here you’ve asked to call you Mica?”

Clever. He’s asking if I have friends yet.

I shake my head no. “Just the caretakers.”

“Your host family?”

I nod.

“I bet everything feels pretty different right now,” Mister Royce says. “It’s hard to know what you can say and do, and who you can talk to. Well, you can talk to me. You can ask me or tell me about anything you want, and I won’t get mad. I might not be able to answer everything right away, but I won’t get mad. Okay?”

I nod again, but don’t look right at him. He waits, and I wait, and I try not to cry.

“You know, even grown-ups have trouble saying what they want to sometimes.”

I am not sure if I should nod.

“I heard that you’re a great writer.” He selects a miniature notebook and pencil. “What if you just took some time to jot down anything you’re feeling? Like a diary entry, just for you. Don’t worry about it sounding perfect or even making sense. Nobody needs to read it but you. But afterward, maybe you’ll have some ideas of things that you want to talk about.”

He slides the child’s tools across to me. Charlie would remind me that I am a child, that I’m the youngest of the generational mission. I take the pencil and start writing.

Dear Diary,

“Earth” is stupid name.

“Most advanced species,” and decides to call home planet “dirt,” “mud,” “soil.”

All other planets better named, especially Neptune. Even fictional species and home worlds have better names. I bet the extra-solars have better names. Mother will tell me when she gets back from her meeting with them.

I would have gone with her if she had let me. Interstellar travel can’t be more dangerous than grade school on planet Dirt.

I worry I will fail lunch. I can read, and write, and do a lot of math in my head better than older students, but there is no teacher for lunch, and I can’t tell who is the officer of the mess hall. The other students sit in groups, and I can’t tell the rules for who sits where and why.

I don’t actually need to interact with the mess staff. I bring my own bag, because female caretaker says I need to ease in to American food; male caretaker jokes about me eating military rations.

I don’t know if I need to interact with the students. I find an empty table at the edge of the big room and start eating.

Someone approaches me. He is the short boy with glasses who was in my old class, before I got moved.

“Hi,” he says.

I do not respond. Perhaps I should have reciprocated.

“Can I join you?”

My jaw drops before I realize he means to share the table. Mother says only Brother can join with me, until I’m old enough to know how adults join—I have theories, will ask Charlie someday.

I close my mouth and nod. Short boy slides a chair to sit across from me. It screeches against the floor polymer, like a docking seal that missed and has to shift and scrape.

“How is Mister Faris? I heard he’s chill.”

Having no concept of my new teacher’s core temperature, I shrug one shoulder.

“You know, people are saying that Miz Lu yelled at you for being from Neptune Station, then fainted when your squid came out.”

“What?”

“I think that’s kind of cool,” he says, then takes a bite. Chews once and resumes, “Kind of like a guardian that shows up to defend you. Do you watch anime?”

“I don’t—”

“I can recommend some. Student accounts have a streaming service.”

I have a vague understanding of anime, but this is not the most pressing point. “I don’t have a squid.” I say the word like it’s something icky, something I don’t want to pass over my tongue, but I’d rather spit out than swallow.

“Oh, your …” He pointed at me—no, at my backpack. “Everyone calls them squids. Even in the news, they—”

“The Neptunians?” I ask. It’s a stupid question. I know that’s what he means.

“Yeah, well, my dad says they’re not really from Neptune, not originally. That’s how they know how to travel.” He shrugs. “What do they call themselves?”

I shake my head. “They don’t call themselves anything. They don’t need to.”

“Oh … so how do you know they don’t like to be called squids?”

I don’t have an answer. I take a bite of my MRE.

He does not comment on the packaging.

“You know, my dad says your mom is a hero.”

I nod. I’d been hearing that a lot. This place called “Washington, DC” keeps talking about heroes. I’ll have to ask Charlie.

Charlie’s full name shows up first, with her personal e-contact: Charlotte Campbell.

Then, the live video feed loads in. It shows Charlie’s face, and behind her the room. She is sitting at a desk, and she has filled the walls with her posters of ancient rockets and even older guitars. Two of her brother’s arms are visible, both draped over her right shoulder.

“Hey, girl!” she says. Big smile.

Makes me feel warmer than thermocoils in a pressure suit. “Hi, Charlie.”

“How you doing, Mica? I heard from your host family that you’re having a hard time with school.”

I nod. A part of me wants to just complain, but another part of me is happy to see her. It’s only been days since we last saw each other in person, when we landed in the Florida Sea, but I really miss her. Seeing her feels way more like home than I think even an orbital station would.

“Tell me about it,” she says, and looks caring even though she’s still smiling.

Charlie is really pretty. Mother calls her “the good kind of pretty.” I think it’s because of her smile. Charlie’s hair is short like mine—more efficient for putting on and sealing up helmets—but she has dyed the front of hers purple. This also makes her look more fun, even though Charlie is practically an adult. She’d had a job called “apprenticeship” back in home biome. She said that this trip to Earth school would be like a little vacation.

“I don’t like the exchange program,” I begin, and wish I’d started with more context. So I trip over myself recounting the last few days, including the fight, and getting switched out of class, and not feeling like I belonged anywhere or with anyone.

While I’m talking, I can feel Brother starting to tremble. Echoing fear and sadness responses I’d been feeling.

“I’m sorry, Mica. Have you talked to your host family about it? They seem really nice, and they’ve both been farther than the moon. Oh, and Missus Rasmussen was in Exocorps, just like your mother.”

She is right, that caretakers—Rasmussens—are nice, but still not like home. Still not familiar with or comfortable seeing Brother.

I chew on my lip. Brother reaches one arm to my neck and applies cooling suction. Obvious sign of tension, sensed by symbiote, visible to Charlie.

Charlie tilts her head to one side. “Sorry, girl. You know, some parts of the adjustment are just going to be hard. Remember Titan Station? Hard at first, but you got through it.”

“I guess,” I admit. There’s a word Mother uses for when you do something because you kind of have to but really don’t want to do. …

“What can I help with?” Charlie asks and then tries to answer. “We could have calls like this every night if you want, same time. Or if you need any equipment or programs, I can write to the Rasmussens.”

“Everyone hates Brother here,” I tell her. Not really an answer, I know.

“Oh, I’m sure they don’t hate your brother, Mica. It’s just that—” She makes a gesture with her hands that means she doesn’t know what to say. “Look, they don’t understand. They haven’t really seen or grown up with symbiotes like we have, so it’s kind of scary and weird to them.”

After waiting the appropriate amount of time for the transmission, I blurt out, “But Brother isn’t scary, and he can’t and won’t hurt anyone.”

Charlie starts to say, “I know that—”

“And he’s not a squid!” I finish, yelling it loudly enough that maybe I upset male caretaker downstairs.

Charlie’s eyes look concerned. She changes subject a little. “Hey, Mica, you know, you don’t have to wait for transmission lag here. We’re actually at less than a second delay. It’s kind of a cool thing about being on the same planet.”

I say nothing.

“Look at it this way: you know about something that none of them do. You are friends with something that scares all of them. You are so brave, and they don’t know how to be that brave. Ah!” Charlie holds up a finger to stop me talking as soon as I start to open my mouth—she’s right, no lag. “You can’t fix that right away. And it’s hard. It can be super lonely, girl, but it’s only because you are so awesome. You are the single bravest person I know, and you’re here on Earth, and representing the Project in Washington, DC. That is incredible!”

“I’d rather be in Cape Carnival with you.”

Charlie smiles again. “It’s Cape Canaveral, sweetie; it’s not a carnival, just another city. And …” She shakes her head. “And there was an agreement about where the Neptune Station kids would live—stay. While the team is away. They only get seven of us to spread between the cooperating nations, and it might be as short as a few months, so …” She shrugs. She really doesn’t know what to say. “Earth is full of politics. And we need to get through the politics to stay in funding.”

Charlie is saying something that her father likes to say. Mother doesn’t even use nice words when talking about politics, then she tells me not to repeat those words. I still sort of wonder if politics is a bad word. Not enough data.

“I know it doesn’t all make sense, Mica. But this is your mission. Your mother is off on a mission—a really important mission, and you have one too. I know it’s a lot, but I know you can do it.”

I straighten up. I know I’m sitting, but Mother says I’ve known how to “sit at attention” since age two. I nod to Charlie, who is old enough to look like a grown-up. “Yes, ma’am,” I say, like they do on the station—actually, like Charlie says to the staff sergeant. I miss the staff sergeant, too.

“That’s what I like to hear.” Charlie looks around, then leans in, like she’s about to tell a secret.

I know she’s far away, but I lean toward my camera too. Brother begins to buzz in anticipation, and I can see Charlie’s brother arching one arm.

“And you were totally right for punching anyone who tries to touch your brother. I know Commander Kessler can’t answer right now, but she would commend you.”

She would commend me! I feel so full and happy that I don’t even realize I’m crying again until Brother comes to collect the tears. Mother used to tell me how lucky I was that I always had someone with me to wipe away the tears, that I would never be alone, that I would be cared for by a symbiote that no one on Earth would ever really understand. Mother is second-generation Neptune, first person to even link with three symbiotes at once, so she knows what she’s talking about. And I’m third-generation Neptune, and I’m brave enough for this mission.

Dear Diary,

Today was better at school. Teacher-Faris is more “chill” than Teacher-Lu.

Short boy with glasses sat with me at lunch again. His name is Franklin, which he says is better than Frank Junior, which I don’t get. He is nice, is okay about seeing Brother now, but a little weird about it too. He is also weird about me being two years younger than him and still taller. When I tried to explain that I might be more than that younger because of time dilation on my trips to Titan and now Earth, he got excited but confused.

He said his dad (Frank Senior) knows about time stuff and is part of X-Force and knows more about the Neptune team’s mission. Also says it’s dangerous for civilians to be on Neptune Station right now, just in case of “something.” I don’t know what—neither does Franklin, really. But I see a lot of stuff about the Trans-Solar Project and someone named SETI. And there are cartoon images of Neptunians, of the symbiotic Xeno-orgs, but most people like calling them squids. Franklin says there’s good anime, bad anime, and anime he’s not allowed to watch—but that good anime shows Neptunians as good guys. I like that.

Franklin asks about how Brother is connected, why it goes into the spine, if it ever hurts. I get to teach him about it, which is kind of cool.

Mister Royce stops reading the diary entry, sets it down and looks at me. He is pleasant. Also lets me keep the backpack open while I’m in his office. Doesn’t flinch at the sight of Brother. Doesn’t ask stupid questions, like if he can touch Brother.

Brother gets to stretch and breathe better when I’m here. Right now, is hugging my arm.

“So, Michaela,” he says, “does it ever hurt?”

“What? No.” I shrug. “Only if someone tries to take him off.”

“That would be worse than hurting.”

“Exactly,” I say. “Mother says it’s a dual-edged sword. Symbiote attachment is the best way to keep babies safe in variable grav and with any risk of pressure or temp changes, but it’s more dangerous to separate later. Mother was disconnected for three days once, and would have lived if she stayed disconnected, but said it was the worst days of her life.”

“I see.”

“Charlie says our immune systems wouldn’t be able to handle Earth without the symbiote, anyway.”

“Oh, yes, Charlotte Campbell. I actually just talked to a colleague about her. She’s thriving in the accelerated program. Sounds like a wonderful influence to have. I heard she’s thinking of going to Annapolis, which is really close by.”

I start to get excited, but Brother notices my wariness and helps keep me in check. “Like visiting soon?”

“No, she’s considering it for college next year.”

“Next year?” I can feel Brother starting to adjust temperature to compensate for me; I can feel room stop spinning before it starts, dizziness and nausea averted. “But we’re not going to be here next year,” I tell him. “We’re going home. Aren’t we?”

Male caretaker does not try to stop me as I run to my room and slam the door. He calls after, “Mica, are you okay?” but doesn’t try to follow. Then I hear him say something frustrated that I’m not supposed to repeat.

A little while later, he is on the phone.

“Hi, Nell?” Pause. “No, I think something new happened. … Well, I didn’t really get a chance to ask her, but I haven’t heard anything from the school. … No, it might be better for her to talk to you. She’s just more comfortable with you, that’s all. … I’ll check on her, but—well, Nell, she’s probably listening to everything I’m saying anyway, with the symbiote.”

He isn’t wrong.

I go to the computer, turn on to try to call Charlie, but she’s off-line. Try anyway, but she’s really off-line. I input clearance codes, and open long-range communication. Don’t care if it’s hours delayed or if Mother won’t be the first to see it. I can still record and send something. But there’s a banner on Neptune Station saying “Not Receiving at This Time.” It suggests I send to Io or Titan Station, the waypoints while we can’t contact Neptune.

Then, I do the thing the caretakers keep telling me not to do: I go to the search bar. I look for exchange program and confirm: not real exchange program. No one exchanged, no one sent to Neptune in our place. I search for Neptune Station and the Trans-Solar Project. I look for the symbiotes and the SETI and the classified things about Mother. Commander Kessler is a hero, it tells me, and she is leading a team on a mission made possible by Neptune Station and Neptunians, by symbiotes like Brother, but where she’s traveling and how far away and how long is classified.

Brother is twitching nervously. Does not know how to help, can only alter endocrine system so much. Cannot rewrite thoughts with chemistry. Tries though. So busy with blood pressure and adrenaline reg that can’t even catch tears—

“Mica?” Voice of female caretaker. She opens the door.

I continue search, harder to see though. Am shaking, whole body.

“Mica!” She rushes to me and pivots my chair. “Honey, what’s wrong?”

I don’t know what I say, and I don’t know if I make any sense. I try to tell her about the long stay and it not being a real exchange program, and how I can’t contact the station and how Mother is gone—and where is she, and is she coming back.

Then female caretaker says, “Come here,” and puts her arms around me. She squeezes me and the being on my back. Brother doesn’t mind. In fact, Brother misses hugs.

“What happened?” she asks.

“I just want to go home.”

“Oh, honey, I know. I’m sorry we can’t make it easier here.”

I wipe my nose and look up at her. Nell Rasmussen, female caretaker, is not as pretty as Charlie, and not Mother. But she looks sincere.

So I ask her, “How long?”

She exhales long enough that I know she’ll tell the truth, even though she doesn’t want to answer. “Honey, we just don’t know. Your mother and the Trans-Solar team and all of the Neptunians who went with them—they have gone on a farther and stranger journey than even your flight here. And it’s hard to say if it’ll be a day, a week, or even months before we hear from them again.”

“I miss Mother. And I don’t like it here. I don’t like wearing the backpack or hiding Brother or having no one understand what it’s like to have a real Brother, instead of just another kid living near you.”

“You know, I’m sure the first people to Neptune Station didn’t like it there either.”

I give her a questioning look.

“No, really. That was fifty years ago. Almost as old as I am. But that was in the early days of beyond-Belt exploration. Their rockets were bad,” she said, shaking her head with a grimace like she was about to spit out spinach whose vacu-pack had leaked. “And they even took one apart to make the station. So they were stuck there, and it felt so alone, so dark, and so cold. But if they hadn’t stayed there and completed their mission, they never would have met Neptunians and found symbiotes.”

Brother has mostly relaxed now. One of his arms is wrapped around Nell Rasmussen’s wrist, gently urging her to stay and accepting her comfort.

“They made it work,” she says. “And things got better. Your mother is making something incredible happen that only a few people really know about, but no matter how weird it is, she will make it work. And, Mica, you are one of those pioneers. I know that you can make it work too.”

Dear Mother,

Avoided a fight at school today. Would have made you proud.

Little native Earth girl, same one, saw me walking through hall this morning, and called out, “Ew! Put the squid away!” Then snickered.

I paused. I walked back to her. Then, took off the backpack, let it drop to the floor, let Brother slide out. Invited Brother with a thought to wrap like he would normally. One true arm over the front of each of my shoulders, one amorphous arm on each side of my neck.

I smiled at little native Earth girl. Her face went white.

I told her, “The squid is my brother.” Then, turned and walked away, letting her—and everyone—see Brother, just like we do on the station, out of the hole in the back of my shirt.

They cannot tell me I need to put it away. I am an ambassador for Neptune Station; take my mission seriously.

Don’t know where you are, or when you’ll be back. Miss you, but I have a mission, too. Will make you proud.

Love,

Michaela Kessler