At midcentury, wrote poet and Trappist monk Thomas Merton, mankind was suffering “acute inner restlessness” and “threatened by the deepest alienation.” North Korean troops were on the verge of driving the United States Eighth Army into the China Sea. The newly proclaimed People’s Republic of China had just launched a full-scale invasion of Tibet. The U.S. government put scientist Edward Teller in charge of developing a hydrogen bomb. The cold war had penetrated deep into the human psyche.

It’s hard to remember how little people in the West knew about Zen—or any other kind of Buddhism—in 1950. Poet Gary Snyder says that when he wanted to learn how to do sitting meditation, he had to imitate a statue of the Buddha in the Japanese garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. If people back then thought about Zen Buddhism at all, they probably connected it with Japanese militarism and World War II.

About 2,500 years ago Siddhartha—“He who accomplishes his goals”—Gautama, the thirty-five-year-old prince of a north Indian warrior clan, decided after years of spiritual struggle to plant himself beneath a tree near the town of Bodhgaya and not move until he achieved enlightenment. Seven days and seven nights later, Gautama had become the Buddha, “the Awakened.” For the next forty-nine years, the Buddha walked around India with a community of people from all castes and walks of life, spreading the truth, the dharma, the method by which suffering is overcome and freedom is attained.

Zen Buddhism is an attempt to follow the Buddha’s path. What is Zen? The word means “concentration” or “meditation.” Zen arises out of “contradictoriness,” Allen Ginsberg once explained to an interviewer from the Buddhist magazine Tricycle, “based on the fact that things both exist and don’t exist at the same time.” The aim of Zen is enlightenment, or satori—the absolute point where no dualism remains in any form.

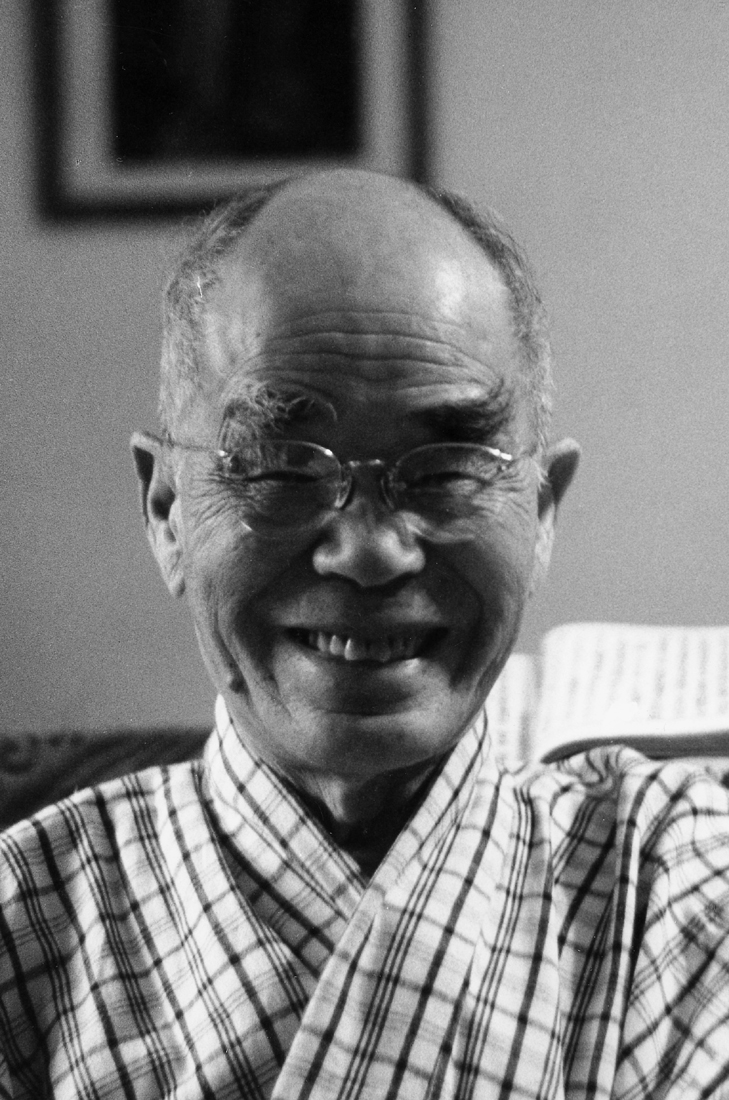

D. T. Suzuki in New York, early 1950s.