By the end of the 1950s, cool was getting hot. With the explosion of television and independent cinema and American teens’ embrace of cool rebels, cool was becoming a commodity.

In 1944, in the mainstream media, there was still something slimy about cool. In Robert Siodmak’s Phantom Lady, one of the most expressionistic and psychologically charged of all film noirs, the jazz drummer, Cliff, played by the pint-sized Elisha Cook Jr., is a leering grotesque in a zoot suit. “You like jazz?” he asks Ella Raines, the girl he’s just picked up, who is masquerading as a band groupie in an attempt to discover who really murdered her boss’s wife. “I’m a hip kitten,” she winks. “Ooh, baby,” Cliff grins in anticipation, leading her down the steps into a Manhattan basement for a whiskey-fueled jam session.

By the mid-fifties, cool had come up from the underground in a slew of mainstream movies aimed at teenagers. Cliff’s swaggering, aggressive, hot sexuality had evolved into a potent, laid-back cool. In Laslo Benedek’s The Wild One (1954), Marlon Brando, sporting sunglasses and a leather cap in his role as the leader of one of the two outlaw motorcycle packs that’s taken over a little town, deliberately set out, he told biographer Bob Thomas, “to do something worthwhile, to explain the psychology of the hipster.” To Brando, a hipster was somebody brave enough to stand against the whole world, yet cool enough not to make a big thing out of it. “Hey, Johnny,” the local coffee shop waitress calls out to him, “what are you rebelling against?” Brando’s shrugged comeback came to symbolize cool in the fifties: “Whaddya got?”

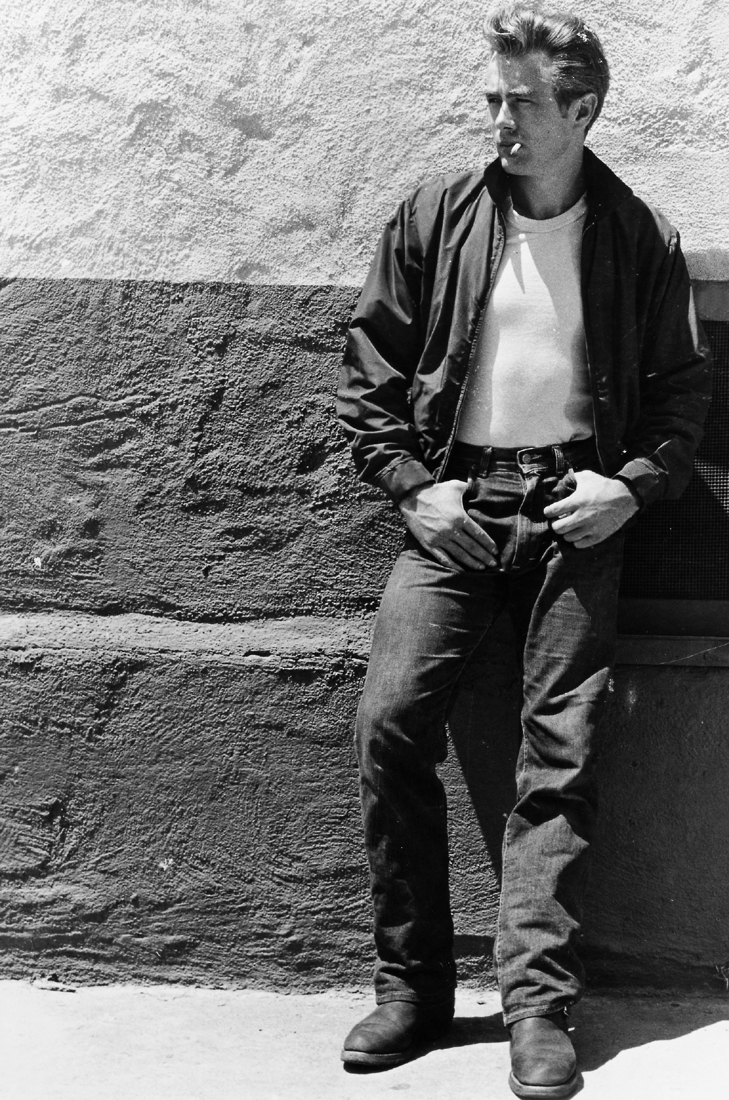

As the troubled teen trying to make sense out of his life, James Dean in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause (1954) showed every high school outsider coping with the world’s hypocrisies that he or she could be cool. “Mom, Dad, this is Judy,” Dean mumbles shyly, introducing Natalie Wood to his parents at the end of Rebel. “She’s my friend.” With the right attitude, the right stance, even a loser can get the girl. When Bill Haley and the Comets sang “Rock Around the Clock” as the credits rolled over a New York cityscape of finger-popping, head-bobbing, tousle-headed hip urban teens in Blackboard Jungle (1955), cool exploded from movie screens across America. Movie cool was no longer the province of gangsters like Paul Muni and George Raft, but of the misunderstood.

James Dean in Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause, 1955.