In his book How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, Serge Guilbaut asserts that Pollock, in his painting, was the one American capable of meeting the Atomic Age head-on. “The effect,” Guilbaut writes of Pollock’s work, “is one of bedazzlement, such as can be caused by staring too long at the sun.” But it is “not the sun,” he goes on, “but its equivalent, the atomic bomb, transformed into myth.”

Life magazine helped make Pollock its first art star. But Life’s readers weren’t as interested in Pollock’s work as in Pollock himself. That’s why Life posed him in front of his painting. To the faceless strivers described in The Organization Man, The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, and The Lonely Crowd (to cite only three middle-class-skewering tomes of the period), Pollock must have looked like an agent of survival, the rebel artist who could face down the Bomb and the world of paranoia, guilt, and fear that it had helped create. But they didn’t actually want to rebel themselves—not yet, because they could see from Pollocks’s picture in Life what it still cost to become cool.

The first time Jackson Pollock ever laid eyes on Arshile Gorky was in 1931, in a lunch room at the Art Students League on Fifty-seventh Street, soon after Pollock had blown into town from Los Angeles. Just turned twenty, with blond hair down to his shoulders, Pollock, busy busing tables, was craning to overhear the dialogue boiling up from a table where Gorky and Stuart Davis were the center of attention. The subject was modern art.

The Art Students League was the place where New York’s most ambitious young artists came to test themselves. Long ensconced on West Fifty-seventh Street by the time Pollock got there, the League had operated for half a century on the principle that, as painter John Sloan put it, a student could “choose his studies much as he can choose his food at the automat.” There were no required courses, no attendance taken, no efforts to regulate the instruction of the thousand or so students. Many of the city’s best artists, from George Bellows to Edward Hopper, were on the faculty.

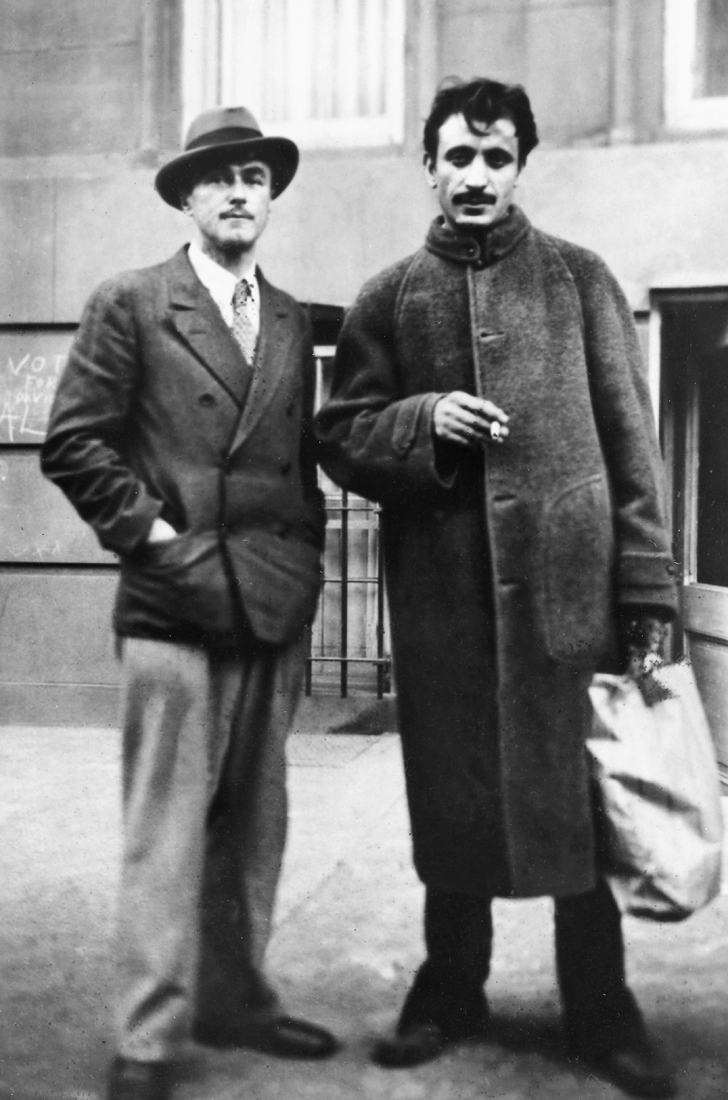

John Graham and Arshile Corky, circa 1934.