Zen teaches two basic routes to satori: zazen, long-term meditative sitting in the same posture the Buddha sat in, and koans, impossible riddles, brain-cracking conundrums like the famous “sound of one hand clapping” that are passed from teacher to student. Both methods stress intuitive knowledge—wisdom transcending ordinary rationality. Solving a koan is impossible—yet all things are possible. Therefore, struggle with a koan is a strong spiritual preparation for a life of cool.

Teitaro Suzuki was born in 1870 into a family of physicians that for several generations had served a provincial samurai clan that had been impoverished almost overnight when the Meiji Emperor, Mutsuhito, abolished the feudal system. Suzuki’s father died when the boy was six, leaving the family bereft of educational opportunities or a place in the world. At seventeen, Suzuki was forced to drop out of high school to support his mother. He used his rudimentary self-taught English to get a job teaching the language in a remote fishing village. “These misfortunes,” he later wrote, “made me start thinking about my karma.” Rinzai Zen, with its studied indifference to life and death, its austere and formal meditation practice, its Spartan monastery life, and its code of total obedience to a master, had long been associated with the samurai. Because of his samurai heritage, it was natural that Suzuki would turn to Zen. After his mother’s death relieved Suzuki of financial responsibilities for anyone but himself, he entered the monastery at Engaku-ji in 1892.

The basic rule of conduct in Zen monasteries hasn’t changed since the first century A.D.: “A day of no work is a day of no eating.” As a novice monk Suzuki’s life at Engaku-ji was rigorous and austere. He rose at 3:30 A.M. to meditate, sitting for extended periods in the cross-legged lotus position, encouraged to remain immobile by blows from a long wooden stick wielded by a senior monitor. Begging for their rice gruel, working at repetitive, menial tasks, the monks endured bitter winter cold with nothing but a tiny charcoal brazier for heat as they grappled with their koans.

In 1893, Suzuki’s master, Shaku Soen, the abbot of Engaku-ji, received an invitation to a World Parliament of Religions scheduled to take place in Chicago. Soen asked Suzuki to write his acceptance letter, then accompany him and act as translator on the trip, the first known visit by a Zen Buddhist teacher to the United States. But Suzuki wouldn’t be able to go until he solved the koan that Soen had given him: “Mu,” meaning “nothing.”

In Zen and Japanese Culture, Suzuki wrote, “No great work has ever been accomplished without going mad.” Indeed, Buddhist literature is full of desperate monks on the verge of suicide because they can’t crack their koans. On the eve of his departure for the United States, Suzuki finally gave up on Mu and became the answer, and everything was cool.

As he remembered years later, the night after solving his koan, Suzuki was walking back to his quarters from the temple when he noticed “the trees in the moonlight. They looked transparent, and I was transparent too.” Soen gave Suzuki a Buddhist name, Daisetz, which Suzuki told people meant “Great Stupidity.” Others translated it as “Great Simplicity,” implying a “skylike” mind emptied of all contradictions.

In Chicago, Suzuki met Dr. Paul Carus, the director of the Open Court Publishing Company in LaSalle, Illinois—a press primarily dedicated to reconciling science and religion. Suzuki’s teacher went back to Japan, but Suzuki remained. He spent the next eleven years at Open Court translating some of the principal works of Buddhism into English, and working on the first of what would ultimately be an estimated 140 books on Buddhism in Japanese and English. On a lecture tour with his teacher, Suzuki met Beatrice Erskine Lane, a Radcliffe graduate and a Theosophist. Suzuki returned to Japan, with Lane, where they married in 1911, and lived in a small house at Engaku-ji. In 1919, they moved to Kyoto, where he became a professor at Otani University and taught courses on Zen and Western thought, while he and Lane published what was probably the world’s first English-language Buddhist journal, The Eastern Buddhist. After Lane’s death in 1939, Suzuki spent the war years in scholarly isolation at Engaku-ji.

In March 1947, two young Americans with an interest in Zen, Richard de Martino and Philip Kapleau, took a day off from their jobs with the International Military Tribunal helping to decide the fates of twenty-eight accused Japanese war criminals, and paid a call on Suzuki. After visiting with them for a while Suzuki knew it was time for him to return to the United States. In the winter of 1950–51, the seventy-seven-year-old scholar arrived in New York to lecture on Zen Buddhist philosophy at Columbia University.

The Department of Religion’s new visiting professor’s age, wit, buoyant spirit, and air of gentle, bemused detachment caught the public’s fancy. Without any care or effort on his own part, Suzuki became an improbable celebrity. He was profiled in The New Yorker, interviewed in Vogue. Tiny, with, as The New Yorker put it, the “slim restless figure of a man a quarter of his age,” impeccably dressed in the style of a Columbia undergraduate in a sport coat, khaki slacks and bow tie, Suzuki was, to the American mind, the very embodiment of Zen. “One cannot understand Buddhism,” Thomas Merton said after meeting Suzuki, “until one meets it, in this existential manner, in a person in whom it is alive.”

Suzuki wasn’t a monk, as he was the first to acknowledge, and he practiced zazen only occasionally. He never pretended to be a roshi, a practicing Zen master, nor did he claim to have received the “dharma transmission,” the wordless “mind-to-mind” transfer that is the master’s seal of approval. Nevertheless, more than any other single person, Suzuki was responsible for what Robert Thurman, Columbia University Buddhist studies professor and the first Western-born Tibetan Buddhist monk, calls in his book Inner Revolution a “cool, inexorable, inner revolution,” a social transformation based on individual transformation. Suzuki inspired an entire generation of “bodhisattvas of cool”—new, cool heroes indifferent to privilege, dogma, and attachment, in but not of the world.

By 1952, John Cage was already on his way to becoming one of the most influential composers of the twentieth century. By the early 1940s, in compositions like the Imaginary Landscapes series, he was already incorporating many instruments and electronic sounds never heard before in Western music: tin cans and lead pipe, oscillators and buzzers, a piano “prepared” by attaching bolts and wood screws to the strings. Thanks to a widely publicized and well-reviewed 1943 Museum of Modern Art concert that had been featured in Life magazine, the then thirty-one-year-old composer was the best-known avant-garde musician of his time.

Los Angeles–born (in 1912) and raised, Cage was the only child of an inventor and the women’s-page editor of the Los Angeles Times. After dropping out of Pomona College and wandering around Europe thinking that he might become an architect, Cage enrolled at the New School for Social Research in New York.

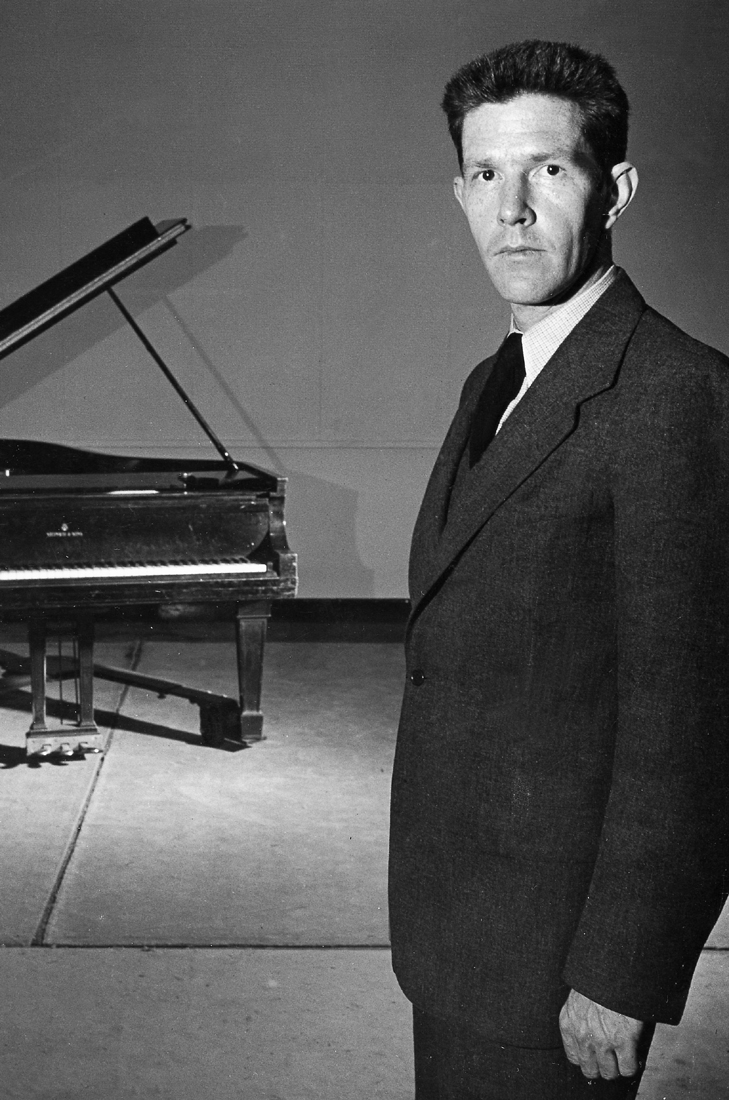

John Cage, 1940s.