CHAPTER 10

Acid and Base Physiology

Introduction

There is a vast amount of water in the human body, distributed as the cytoplasm within cells (intracellular fluid) and the extracellular fluid, which includes plasma. Dissolved in all of these fluids are a wide variety of solutes (i.e., particles that are dissolved). Among the most important solutes are acids and bases. By the Brønsted-Lowry theory, acids are compounds that, when dissolved in water, will donate a hydrogen ion (H+); bases are compounds that, when dissolved in water, will accept an H+ from an acid. Examples of acids include hydrochloric acid (HCl) and carbonic acid (H2CO3); examples of common bases include ammonia (NH3) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH).

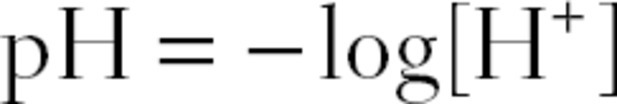

We measure the concentration of acid in the body fluids using the pH scale. The pH of a solution is defined as follows:

where [H+] is the concentration of H+.

If there is an abundance of acid in the fluid, there will be a high [H+]. This corresponds to a low pH; the lower the pH measurement, the more acidic the fluid. If there is an abundance of base in the solution, there will be a relatively lower [H+], because bases will eagerly accept and incorporate free H+. This corresponds to a high pH; the higher the pH measurement, the more alkaline (basic) the fluid. In chemistry, a pH of 7 is considered neutral, a pH less than 7 is considered acidic, and a pH greater than 7 is considered alkaline.

In human physiology, however, the optimal pH of arterial blood is 7.4, or slightly alkaline. When the pH of the plasma is less than 7.4, the plasma is acidotic. When the pH is greater than 7.4, it is alkalotic. Venous blood will naturally have a lower pH, as it is carrying more acidic waste from the periphery for removal by the lungs, kidneys, liver, and bowel.

The balance between acids and bases is crucial to proper body functioning. Even slight deviations from a pH of 7.4 can result in serious consequences. For example, reduction in pH to less than 7.0 (from the optimal pH of 7.4) can be detrimental (even fatal) because the organs and tissues of the body depend on the functionality of their cells, and the cells are functional only with enzymes. Enzymes are special proteins that catalyze chemical reactions. Alterations to the body’s acid-base balance change the chemical structure of these enzymes, resulting in cell and organ malfunction.

Physiologic Consequences of Acid-Base Disturbances

In the operating room (OR), acidosis produces its most significant and obvious effects on the cardiovascular system. As pH drops to 7.2, there is a noticeable reduction in heart muscle contractility, and at a pH of 7.1, the entire cardiovascular system becomes much less responsive to catecholamines, making it very difficult for the anesthesiologist to treat hypotension with commonly used agents (e.g., norepinephrine, phenylephrine, ephedrine). Acidosis may further exacerbate the likelihood of end-organ damage because acidosis also causes hypotension due to peripheral arteriolar dilation and constriction of the pulmonary arteries. The combination of acidosis-induced reduced cardiac contractility and peripheral dilation causes direct hypotension. Acidosis-induced pulmonary artery constriction may cause right-sided heart failure, which worsens hypotension. Importantly, acidosis results in shifting of potassium out of cells and into the general circulation, which results in additional cardiac dysfunction.

Respiratory Acid-Base Disturbances

The acids in the body come from a variety of sources. When proteins are metabolized, weak acids are released into the bloodstream. But the main contribution of acid comes from a gas. When cells metabolize fats and carbohydrates, carbon dioxide (CO2) gas is produced. Inside of cells, this CO2 dissolves in the cytoplasm, producing H2CO3.

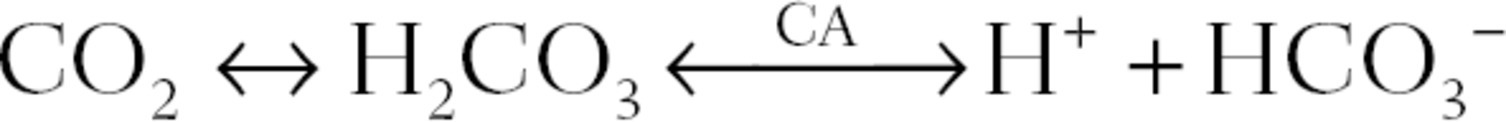

The enzyme carbonic anhydrase (CA) rapidly converts this H2CO3 into H+ and HCO3− (bicarbonate), which can be illustrated as follows:

As illustrated above, CO2 production results in an increase in [H+]. This translates into a lower pH. Therefore, excess CO2 leads to acidosis. If CO2 were not removed from the body, acid would build up and pH would decrease dramatically. Fortunately, the CO2 produced in metabolism is transported in the bloodstream to the lungs. Here, it is removed from the blood in exchange for oxygen (O2) and is breathed off into the environment. CO2 travels in the blood in three forms. The majority of CO2 dissociates into H+ + HCO3− (bicarbonate anion). The H+ binds to hemoglobin molecules (Hb·H+), while the HCO3− travels freely in the plasma (often in association with salts, like sodium). Once at the lungs, the H+ and HCO3− recombine to form CO2, where it is exhaled. A small amount of CO2 also travels as dissolved CO2, and a small amount binds directly to hemoglobin (Hb·CO2).

When acidosis is caused by the lungs being unable to breathe off CO2, it is termed respiratory acidosis. Respiratory acidosis occurs when ventilation is impaired. Two common examples of respiratory acidosis are when ventilation is reduced because the patient received high doses of opioids or other systemic anesthetics and when a patient is being inadequately ventilated by a mechanical ventilator. Another example is when respiratory muscles are weak. A paralyzed diaphragm can be observed following interscalene blockade. Intercostal muscles may become weak in patients with a high spinal or epidural anesthetic. All the muscles of respiration are weak before full recovery from neuromuscular blockade. Decreased ability to clear CO2 from the lungs may also occur secondary to extremely diseased lungs. Respiratory acidosis also occurs when there is excess production of CO2, beyond the patient’s ventilatory ability. For example, in patients who are anesthetized and mechanically ventilated (i.e., have a fixed ventilation), excess CO2 production may occur from high fevers or malignant hyperthermia. Patients with acute respiratory acidosis may appear anxious or delirious or even have myoclonic convulsions or seizures in extreme cases. The acidosis is best treated by treating the underlying cause or, if necessary, by initiating or increasing mechanical ventilation.

Lungs can also breathe off too much CO2. This is termed respiratory alkalosis. Respiratory alkalosis occurs due to hyperventilation (breathing too fast). This happens in patients suffering anxiety attacks. It is also seen in patients with liver failure, pregnancy, and an overdose of aspirin. Hyperventilation may also be used in anesthetized or sedated patients, at the request of the neurosurgeon, as respiratory alkalosis is known to reduce brain blood flow and reduce intracranial pressures. Patients with respiratory alkalosis might present with arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), muscle cramps, tingling sensations, or even seizures. Although correcting the underlying cause is essential, hyperventilation can be urgently treated with sedating drugs if necessary. In anesthetized and mechanically ventilated patients, hyperventilation can be treated by simply reducing the rate and depth of ventilation being provided by the ventilator on the anesthesia machine.

Oxygen (O2) is another important gas in maintaining acid-base balance. It is inhaled from the environment and enters capillaries in the lungs in exchange for CO2. If breathing is impaired, O2 cannot enter the lungs to be exchanged with CO2. As shown above, the buildup of CO2 in the blood results in acidosis. Furthermore, O2 is essential for aerobic metabolism. When cells lack O2, they produce energy via anaerobic glycolysis, which requires the reduction of pyruvate to lactic acid. Lactic acid quickly dissociates in the body to lactate and H+. Prolonged glycolysis causes the accumulation of lactic acid, which results in further acidosis. Low O2 supply to the tissue may result from systemic hypoxia (e.g., high altitude, poor pulmonary gas exchange) or compromised circulation to an individual body region (local ischemia). Global ischemia may be caused by overall poor circulation (e.g., cardiac failure or severe hypotension), while local ischemia may be secondary to surgical intervention (e.g., aortic cross-clamp, limb tourniquet) or patient disease (arterial blood clot, peripheral vascular disease, trauma, etc.).

Arterial Blood Gases

Because O2 and CO2 are important factors in determining acid-base balance, measuring and monitoring their partial pressures in the bloodstream can provide valuable insight into the physiologic condition of the patient. This is accomplished by arterial blood gas measurement (ABG). A sample of blood is drawn from an artery and is placed into a blood gas analyzer device (see Chapter 35, Point of Care Testing). This device uses a variety of electrochemical probes to measure the pH and the partial pressures of O2 and CO2. It is important to understand that the [HCO3−] is calculated and not directly measured by most blood gas machines. Assessment of a patient’s acid-base status from a reading on the blood gas analyzer can depend on the temperature of the patient and the temperature setting on the machine performing the measurement. Two different approaches exist: “alpha stat” and “pH stat.” In blood, the pH changes inversely with temperature. Thus, at temperatures below 37°C (particularly common in cardiac surgery), a pH of 7.4 would be considered acidotic. With the pH-stat approach, the anesthesia technician will run the blood sample entering the patient’s temperature into the blood gas machine. In the alpha-stat approach, however, all blood gases are run at 37°C, although this may not match the patient’s temperature in reality. Since there is great controversy among anesthesiologists regarding the best approach (alpha or pH stat) in a patient whose temperature is not near 37°C, the anesthesia technician should ask providers their preference before analyzing the sample blood on the blood gas machine.

When obtaining a patient’s vital signs during an operation or at the bedside, oxygen saturation (“pulse ox”) is often measured by clipping a pulse oximeter probe to the fingertip (see Chapter 31, ASA Standard Monitors). Both the red and infrared waves emitted by this probe allow for the measurement of the amount of hemoglobin in the blood that is bound to oxygen (Hb·O2). This defines oxygen saturation (SaO2). Although this gives us a good estimate of oxygenation, it does not tell us anything about CO2 or acid-base balance. This is why we must examine the ABG.

In the OR, many patients who require frequent analysis of an ABG will have an indwelling catheter in a peripheral (usually radial) artery. Many hospitals use a specialized syringe for ABG sampling, which is precoated with 30-100 units of heparin per milliliter of blood to be obtained and fills spontaneously when exposed to arterial pressure. A syringe with too much heparin risks diluting the sample. When preassembled kits for ABG measurement are not readily available, the inside of a regular syringe can be lightly rinsed with heparin (usually 1,000 unit/mL strength), taking care to remove as much liquid heparin from the syringe as possible. Glass syringes are preferable to plastic. If the patient does not have an indwelling arterial line, the proper ABG syringe can be used with a 23-gauge needle to perform a sterile single-stick sample, usually from the radial artery. Once the sample is obtained, expel any air bubbles from the syringe. Then, send the sample (be sure it is labeled correctly) immediately to the laboratory for analysis.

Some institutions use arterial monitoring sets that include a blood withdrawal chamber in a closed system that minimizes blood wastage and contamination. With these sets, blood is drawn back into the chamber and the arterial blood sample is withdrawn from a special sampling port. Withdrawal of the appropriate amount of blood into the chamber ensures that only blood is at the sampling site and not blood that has been mixed with the arterial line flush solution. After obtaining the blood sample for ABG analysis, the blood in the chamber, which will be a mixture of blood and dead-space fluid from the catheters, is infused back toward the patient. Finally, the catheter is flushed using a pressurized fluid system (using a pressurizing compression bag) to prevent blood clotting in the tubing system. Some institutions do not utilize the closed system tubing configuration. In this situation, the clinician will attach a sterile syringe to the stopcock that is most proximal to the patient and withdraw at least three times the amount that is included as dead space in the tubing system. The withdrawn blood must then be discarded and additional blood drawn to fill the ABG syringe. It is important not to force the syringe back with excessive pressure, as this may cause damage to the artery. Finally, flush the tubing system with saline (or heparinized saline) to prevent blood from clotting in the tubing.

There are certain pitfalls in ABG measurement that should be avoided. First, there should be minimal delay in transporting the sample to the analyzer. Within the blood sample, there are cells whose metabolic activity will alter the partial pressures of CO2 and O2. If you anticipate a delay of more than 10 minutes, the sample should be cooled on ice for no more than 1 hour to slow this metabolic activity. In cases of delay, glass syringes are superior as gases may dissolve over a short period of time in plastic. Additionally, any small air bubbles should be expelled from the syringe, as they result in inaccurate analysis (gas from the bubble can diffuse into the blood or gas in the blood can diffuse into the bubble). Large air bubbles indicate an unusable sample that should be discarded. Complications for the patient include mistaken venous sampling, hematoma, excessive bleeding, occlusion of the artery, and infection. A venous blood sample will have higher pCO2 and lower pO2 than arterial blood, and the values may not correspond to the patient’s clinical condition.

ABG Interpretation

pH: Normal range, 7.35-7.45.

The first step when evaluating an ABG is to determine if the pH is in the normal range. If the patient’s pH is below 7.35, the patient is acidotic, and if it is higher than 7.45, the patient is alkalotic.

pCO2: Normal range, 35-45.

Next, review the pCO2. When deviations in pCO2 account for changes in the pH, the patient is said to have a respiratory acid-base disorder. If the pCO2 is above 45 in acidotic patients, the patient has respiratory acidosis; if the pCO2 is below 35 in alkalotic patients, the patient has respiratory alkalosis.

HCO3: Normal range, 22-26.

Next, it is important to analyze the HCO3− (normal 22-26 mEq/L). When the direction of change in HCO3− matches that of the pH, the patient is said to have a metabolic acid-base disorder. If HCO3− is below 22 in acidotic patients, the patient has metabolic acidosis, and if HCO3− is above 26 in alkalotic patients, the patient has metabolic alkalosis. Finally, patients may have alterations in both CO2 and HCO3−. In some cases, this is due to disorders in different organ systems. In other cases, the patient’s body is attempting to compensate for an acid-base disorder and restore the pH to as close to normal as possible. In these patients, the primary cause of the disorder (respiratory or metabolic) tracks the change in pH. Thus, a patient who has a low pH, a high pCO2, and a high HCO3− is said to have a primary respiratory acidosis with a compensatory metabolic alkalosis. Similarly, a patient who has a low pH, a low HCO3−, and a low pCO2 is said to have a primary metabolic acidosis with compensatory respiratory alkalosis.

Metabolic Acid-Base Disturbances

Besides the H+ generated from CO2, other metabolic processes—such as protein breakdown—generate acids such as H2SO4 and H3PO4. It is the responsibility of the kidneys to excrete enough H+ in the urine to ensure that excess acid is not retained in the body. Furthermore, feces are rich in HCO3−, and so every bowel movement results in loss of HCO3−, a base. Again, it is the responsibility of the kidneys to reabsorb enough HCO3− to balance these losses.

When the kidneys are unable to adequately excrete H+ or fail to reabsorb enough HCO3− (to remove excess H+), acidosis results. This sort of acidosis is termed metabolic acidosis. Added H+ is moderated to a limited extent by the body’s buffer system. Buffering is the process by which the effects of increasing H+ concentration are mitigated, utilizing bases to bind to the excess free H+. Buffers can also absorb HCO3−. Finally, molecular buffers can release H+ or HCO3− to counteract pH changes when the concentration of H+ or HCO3− is falling. Hemoglobin buffers pH by directly binding H+. Bone can buffer pH during extreme acidosis by releasing HCO3− into the circulation. But the most important buffer is plasma HCO3−. As acid accumulates in the bloodstream, H+ combines with HCO3−. H2CO3 forms almost immediately and, catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase, becomes CO2 and H2O, and the CO2 is exhaled. Yet, if the body is overloaded with acid, the HCO3− buffer will become exhausted and cease to be effective. It is then that metabolic acidosis seriously affects the pH.

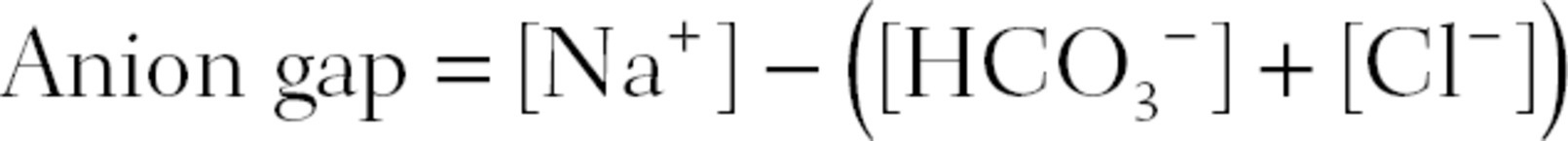

When attempting to find the cause of a metabolic acidosis, you will find valuable clues in the concentrations of electrolytes (ions) in the patient’s blood. Plasma is electrically neutral—all of its positively charged constituents (cations) are balanced by an equal number of negatively charged constituents (anions). The major cations are sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), calcium (Ca2+), and magnesium (Mg2+). The major anions are HCO3−, chloride (Cl−), and proteins. Out of all these ions, Na+, HCO3−, and Cl− are considered the major, “measured” ions. The difference in concentration between the measured cations and the measured anions is called the anion gap.

Normally, the anion gap ranges from 8 to 12. This reflects the concentration of the so-called unmeasured anions, mainly proteins.

In a patient with diarrhea, extensive amounts of base, HCO3−, are lost in the stool. This results in a metabolic acidosis. As HCO3− is lost from the bloodstream, Cl− shifts from within cells to the bloodstream, replacing the lost negative charges, thus preserving electrical neutrality. Because the rise in [Cl−] offsets the fall in [HCO3−], there is no change in the anion gap. This is termed normal anion gap metabolic acidosis. It is treated by replacing lost fluids and electrolytes and quieting the underlying gastrointestinal disturbance. In severe cases, NaHCO3 (a base) may be gradually infused to raise the pH. Normal anion gap metabolic acidosis also occurs when the kidneys fail to reabsorb HCO3− due to damage to kidney tubule cells, when carbonic anhydrase enzymes are inhibited by medications (e.g., acetazolamide), and when there are deficiencies in the hormone aldosterone.

One of the most common causes of metabolic acidosis in the OR is excessive infusion of chloride-containing fluid. This usually results from the anesthesiologist administering intravenous (IV) fluid in the form of normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride). Increases in blood chloride concentration cause the kidneys to excrete HCO3−, and the patient can become acidotic. Unfortunately, this acidosis is often not recognized to be secondary to excess chloride administration, with clinicians confusing this acidosis as being secondary to poor perfusion. The clinician may administer “volume resuscitation” with normal saline, making the acidosis and patient’s condition worse.

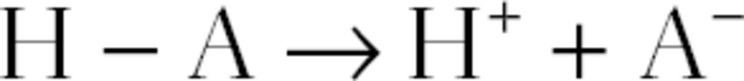

When acids are added to the plasma, the acid dissociates into its ionic components.

The added H+ combines with plasma HCO3−, depleting it. But, since the acid’s dissociation produces an anion (A−), there is no need for Cl− to shift from the cells to the plasma because the lost negative charges of HCO3− are balanced by the added A−. Since neither [Na+] nor [Cl−] changes while [HCO3−] decreases, the anion gap becomes larger. Such a situation is labeled increased anion gap metabolic acidosis.

Certain causes of increased anion gap metabolic acidosis are commonly encountered. In the perioperative setting, the most common cause is lactic acidosis from poor perfusion. In patients whose tissues are starved of oxygen (e.g., systemic hypoxia, decreased blood flow to organs, or, rarely, carbon monoxide poisoning), anaerobic glycolysis predominates. The end product of this process is lactic acid, which results in an increased anion gap metabolic acidosis. In the OR, lactic acidosis is most common during prolonged periods of hypotension or when a large percentage of the body is excluded from normal circulation (e.g., aortic cross-clamp during aortic artery surgery). Severe ischemia, hypoxia, or shock is likely to increase the blood concentration of lactic acid. In critically ill patients, a lactic acid concentration of less than 2 mmol/L can be considered normal. With lactic acid levels of 2-5 mmol/L, the body can usually compensate and the patient may not present as being acidotic. However, lactic acid levels of greater than 5 mmol/L are usually associated with systemic acidosis. Treatment includes improvement of circulation (e.g., pharmacologic treatment of hypotension or removal of cross-clamps) and IV fluid rehydration (for decreased blood flow to organs). In the case of systemic hypoxia (e.g., congestive heart failure or poor lung function), treatment includes administering 100% oxygen therapy by using mechanical ventilation with aggressive use of positive end-expiratory pressure.

Other causes of increased anion gap acidosis occur when acids other than lactic acid accumulate in the body. Aspirin (aminosalicylic acid) overdose decreases the pH and fills the blood with salicylate anions. This is best treated by preventing further aspirin absorption (using activated charcoal) and by alkalinizing blood and urine to encourage salicylate elimination (administer NaHCO3 until the blood pH is higher than 7.45).

Patients with kidney failure are unable to excrete H3PO4 or H2SO4, resulting in the accumulation of metabolic acids. This is remedied by hemodialysis. Patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus accumulate keto acids (e.g., acetoacetic acid) leading to the emergency situation of diabetic ketoacidosis. This is best treated with insulin and IV fluid rehydration.

When the kidneys excrete too much H+, the result is alkalosis. This sort of alkalosis is termed metabolic alkalosis. When a person vomits, HCl is expelled from the stomach. Similarly, inserting a suctioning nasogastric (NG) tube into the stomach to relieve a patient’s gastrointestinal distress also removes HCl. This loss of acid causes metabolic alkalosis. In order to reclaim the fluid volume lost, the kidneys reabsorb more Na+ and water. The Na+ is reabsorbed in exchange for H+, which is excreted from the bloodstream into the urine, exacerbating the metabolic alkalosis. This latter sort of alkalosis is also caused by diuretic drugs (e.g., furosemide) that cause volume loss by increasing urination. Properly rehydrating the patient with IV fluids corrects all of these alkaloses. Certain tumors produce an excess of the hormone aldosterone. Increased aldosterone results in metabolic alkalosis by causing increased Na+ reabsorption in exchange for H+. Aldosterone’s actions can be blocked by medications (e.g., spironolactone) or by surgical removal of the tumor.

Although there are many causes of pH disturbances, ABG results, analysis of electrolytes and the anion gap, and patient history can point you toward a diagnosis and direct subsequent treatment.

Compensation

Changes in pH disrupt healthy body functioning. Fortunately, the body has built-in mechanisms to correct disturbances to its acid-base balance. In patients who are not anesthetized and have metabolic acidosis or alkalosis, ventilation (breathing rate) rapidly adjusts. Breathing faster expels CO2 more rapidly with each exhalation. The removal of CO2 is equivalent to breathing off H+, which makes the pH less acidic. Breathing rate, though, cannot increase infinitely, and this limits the effectiveness of respiratory compensation. On the other hand, breathing more slowly causes less CO2 to be exhaled. Thus, more H+ is retained, and the pH becomes more acidic. Breathing rate can only decrease a certain amount to compensate for alkalosis because a decrease in ventilation also causes a decrease in O2 intake. Consequently, decreased ventilation never lowers the pH quite to 7.4.

The body acts as its own blood gas analyzer by using chemoreceptors. A chemoreceptor is a sensing apparatus that detects concentrations of chemicals, consisting of a sensor that relays information to an integrator. This integrator then instructs an effector to respond accordingly. There are two groups of chemoreceptors in charge of ventilation: peripheral and central. The peripheral chemoreceptors are located in the aortic body (near the heart) and the carotid body (in the neck). They detect pO2, increasing ventilation when pO2 decreases. The central chemoreceptors are located in the medulla of the brainstem (between the cerebrum and the spinal cord). They detect pCO2 and strive to maintain it at 40 mm Hg.

In metabolic acidosis, when H+ is increased, increased CO2 is present in the central nervous system. Central chemoreceptor sensors send a signal to the respiratory centers of the brainstem, which instruct the lungs to increase ventilation. This increase in ventilation decreases the pCO2 and occurs minutes after the pCO2 increase is detected. In this way, pH change is minimized.

When metabolic or respiratory acid-base balance is disturbed for a prolonged period of time, further compensation is provided by the kidneys. They are responsible for maintaining optimal concentrations of electrolytes in the blood. Although their function is very complex, they essentially act as filters, absorbing or expelling ions based on relative concentrations to surrounding blood vessels or tissues. As blood passes through the kidneys, electrolytes may be reabsorbed back into the bloodstream or expelled by the kidney into the urine. The kidney senses alterations in voltage and pH and adjusts its filtering accordingly. For instance, if the blood pH is too acidic, the kidney secretes excess H+ into the urine while simultaneously reabsorbing HCO3− back into the bloodstream. Nevertheless, this compensation never brings the pH back to a normal 7.4. In other words, a chronic (prolonged) acidosis will be compensated to a pH less than 7.4, while a chronic alkalosis will be compensated to a pH greater than 7.4.

Summary

Acid-base balance is crucial for normal physiologic functioning. Alterations in ventilation cause changes in pCO2, resulting in respiratory acidosis or respiratory alkalosis. The loss of HCO3− via bodily excretions, along with the accumulation of acids from ingestion and metabolism, results in metabolic acidosis. The body has its own mechanisms to compensate for alterations in pH. Within minutes, ventilation adapts to compensate for metabolic acid-base disturbances. After 1 day, the kidneys begin to compensate for both metabolic and respiratory acid-base derangements. Unfortunately, the body’s compensatory mechanisms can be overwhelmed; thus, it is essential to treat the underlying cause of the acid-base disturbance, as it may easily become life threatening. Measurement and analysis of an ABG, electrolytes, lactate level, and anion gap, as well as patient history, will guide diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Dr. Aaron Kirsch for his contributions to the content of this chapter in the first edition.

Review Questions

1. Infusing pure HCl will have what effect on H+ and pH?

A) Increase H+; increase pH

B) Increase H+; decrease pH

C) Decrease H+; decrease pH

D) Decrease H+; increase pH

E) Unchanged H+; unchanged pH

Answer: B

HCl is an acid. It will donate its H+ so that the concentration of H+ will increase. An increase in H+ translates to a decrease in pH. If a base were infused instead, there would be a decrease in H+, which translates into an increase in pH (option D).

2. You are asked to see an anxious patient whom you suspect may have respiratory alkalosis. Which of the following studies best assesses the patient’s acid-base status?

A) Arterial blood gas (ABG)

B) Pulse oximetry (pulse ox)

C) Lactic acid level

D) Central venous pressure (CVP)

E) Electrocardiogram (EKG)

Answer: A

The ABG sample is passed through an analyzer machine, providing us with the arterial pH, pCO2, and pO2. This is the most informative study for the patient’s acid-base status. Pulse oximetry only measures oxygen saturation (SaO2). Decreased SaO2 will result in decreased tissue oxygenation and increased lactic acid levels. It is not as informative as ABG. Lactic acid levels increase when tissues are not supplied with adequate oxygen but do not give a good picture of global acid-base status. CVP is a measurement of body blood volume. It is decreased in hemorrhage, but it does not directly inform us about acid-base status. EKG findings are nonspecific and not very informative about acid-base status.

3. A patient experiencing respiratory acidosis may present with which of the following symptoms? (Select all that apply.)

A) Anxiety

B) Muscle cramps

C) Tingling sensations

D) Seizures

E) Delirium

Answer: A, D, and EPatients with respiratory acidosis may appear anxious or delirious or even have myoclonic convulsions or seizures in extreme cases. Muscle cramps and tingling sensations present in patients with respiratory alkalosis. Seizures may present in either acidosis or alkalosis.

4. Which of the following would be the most likely to cause alkalosis?

A) Aspirin overdose

B) Excessive metabolism of fats

C) Hypoxia

D) Excessive vomiting

E) Excess sodium chloride administration

Answer: D

Excessive vomiting would remove stomach acid (HCl) from the body, resulting in a loss of acid and making the body more alkaline. All other answers would cause acidosis. Aspirin is an acid and would cause the pH to decrease. Hypoxia would result in loss oxygen being available to exchange for CO2 at the lungs, resulting in increased CO2 retention and decreased pH. Fat metabolism produces acids as a by-product. Increases in blood chloride concentration cause the kidneys to excrete HCO3−, causing acidosis.

5. Oxygen is required to exchange CO2 at the lungs in order to prevent CO2 buildup from causing respiratory acidosis. For which other reason is adequate oxygenation required for prevention of pH imbalance?

A) Adequate oxygen is needed to sequester H+ ions.

B) Adequate oxygen prevents anaerobic glycolysis.

C) Oxygen, O2, becomes an anion in the body to balance Cl−.

D) High concentration of oxygen is required to activate filtration cells in the kidneys.

E) Oxygen, O2, becomes an anion in the body to balance Na+.

Answer: B

O2 is essential for aerobic metabolism. Without adequate oxygen, cells produce energy via anaerobic glycolysis, which requires the reduction of pyruvate to lactic acid, and prolonged glycolysis causes the accumulation of lactic acid, which results in acidosis.

6. Which of the following organs does not play a role in balancing acids and bases in the human body?

A) Lungs

B) Kidneys

C) Central nervous system of the brain

D) Stomach

E) Gallbladder

Answer: E

The lungs balance acid by increasing or decreasing respiration rate, changing the amount of CO2 retained, which affects acid-base chemistry. The kidneys excrete and reabsorb H+ and HCO3−. Chemoreceptors in the central nervous system sense changes in pCO2 and instruct the lungs to adjust for acid-base chemistry accordingly. The stomach can expel excess acid by vomiting. The gallbladder, however, is involved in metabolism and digestion; while these processes may alter acid-base chemistry, the gallbladder does actively participate in balancing acids and bases.

SUGGESTED READINGS

American Association for Respiratory Care. AARC clinical practice guideline: sampling for arterial blood gas analysis. Respir Care. 1992;37:913-917.

Breen PH. Arterial blood gas and pH analysis: clinical approach and interpretation. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2001;19:885-902.

Gluck SL. Acid–base. Lancet. 1998;352:474-479.

Kellum JA. Clinical review: reunification of acid–base physiology. Crit Care. 2005;9:500-507.

Koeppen B. The kidney and acid–base regulation. Adv Physiol Educ. 2009;33:275-281.

Oosthuizen N. Approach to acid–base disorders—a clinical chemistry perspective. Contin Med Educ. 2012;30(7): 230-234.

Pishbin E, Ahmadi G, Sharifi M, et al. The correlation between end-tidal carbon dioxide and arterial blood gas parameters in patients evaluated for metabolic acid–base disorders. Electron Physician. 2015;7(3):1095-1101.

Williams AJ. Assessing and interpreting arterial blood gases and acid–base balance. BMJ. 1998;317:1213-1216.