CHAPTER 47

Anesthesia Supply and Equipment: Contamination, Sanitation, and Waste Management

Introduction

All health care workers share the responsibility of preventing the transmission of infectious diseases. Anesthesia technicians are on the frontlines in the battle against infectious diseases in the operating room. Multiple pathogens present in our working environment can cause serious illness or death in our patients or coworkers, as the anesthesia machine and associated equipment are potential vectors in the spread of infection. Improper handling and cleaning of anesthesia apparatus can increase the transmission of pathogens, causing postoperative wound infections, respiratory system infections like pneumonia, or infections that invade the bloodstream and entire body.

Both patients and health care workers are at risk. Anesthesia equipment and personnel are in close contact with patients’ blood, mucous membranes (i.e., mouth, nose), and secretions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) call these “potentially infectious materials” (PIMs). Blood and secretions create a moist environment for growth and survival of pathogens such as fungi, yeast, viruses, and bacteria, including Streptococcus and Staphylococcus. These pathogens are covered in more detail in Chapter 23, Infectious Disease. Each hospital has its own unique infection control policy; however, it must also comply with state and federal regulations. It is the responsibility of the anesthesia technician to become familiar with the policies at his or her institution and to follow these guidelines closely. Web addresses for guidelines and recommendations of the CDC, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and the World Health Organization (WHO) are provided at the end of the chapter.

Sterile Operative Terminology

Contamination: This is the state of actually or potentially having been in contact with microorganisms. It may also refer to the presence of pathogens or unwanted foreign material on an object. Contamination may occur via contact with patients, handling by staff, splashing, or contact with already contaminated objects.

Bioburden (bioload, microbial load): This is the number and types of viable organisms contaminating an object. The level of bioburden is related to the anatomic site where the device was used (Fig. 47.1).

FIGURE 47.1. Video laryngoscope blade with bioburden.

Cross-contamination: The transmission of microorganisms. Cross-contamination can occur via contaminated medical equipment or through health care workers (e.g., child’s toy, baby doll use on multiple patients without cleaning) (Fig. 47.2).

FIGURE 47.2. Cross-contamination (child’s toy, baby doll).

Cleaning: The physical process that removes organic or inorganic debris (bioburden) from inanimate or animate objects. It is the first step in the decontamination process. Cleaning or sanitation must be performed prior to disinfection and sterilization. This essential process removes large amounts of organic matter (i.e., secretions, blood, and vomitus) and reduces the number of microorganisms. Cleaning also removes retained salts and organic soil, which can inactivate chemical germicides. Cleaning usually involves an enzymatic presoak detergent along with vigorous scrubbing.

Decontamination: A process that renders contaminated inanimate items safe for handling by personnel who are not wearing protective attire (i.e., reasonably free of the probability of transmitting infection). Decontamination can range from simple cleaning to sterilization.

Disinfection: The process capable of destroying most microorganisms but, as ordinarily used, not bacterial spores. A disinfectant is usually a chemical agent, but some processes, such as pasteurization, are disinfecting. Disinfection is accomplished by using heat treatment or chemical agents.

Low-level disinfection: Destruction of all vegetative bacteria, lipid viruses, some nonlipid viruses, and some fungi, but not bacterial spores. Usually obtained with the use of hospital grade disinfectant solutions.

High-level disinfection: A procedure that kills all organisms except for bacterial spores and certain species, such as the Creutzfeldt-Jakob prion. Most high-level disinfectants can produce sterilization with sufficient contact time (Fig. 47.3).

FIGURE 47.3. High-level disinfection.

Sterilization: A process capable of removing or destroying all viable forms of microbial life, including bacterial spores, to an acceptable sterility assurance level. Methods for sterilization include steam under pressure (autoclaving), dry heat (hot air oven), and chemical sterilants (usually in gaseous forms) (Fig. 47.4).

FIGURE 47.4. Large autoclave capable of sterilizing many surgical trays and peel-packed instruments in a single load.

Spaulding decontamination classification system: This classification system, first proposed by Dr. E. H. Spaulding, divides medical devices into categories based on the risk of infection involved with their use. This classification system is widely accepted and is used by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the CDC, epidemiologists, microbiologists, and professional medical organizations to help determine the degree of disinfection or sterilization required for various medical devices. Three categories of medical devices and their associated level of disinfection are recognized. They are as follows:

Critical: A device that enters normally sterile tissue or the vascular system or through which blood flows. Such devices, if reusable, should be sterilized, which is defined as the destruction of all microbial life. Examples include surgical instruments, intravenous catheters, and Foley catheters.

Semicritical: A device that comes into contact with intact mucous membranes and does not ordinarily penetrate sterile tissue. These devices should receive at least high-level disinfection, which is defined as the destruction of all vegetative microorganisms, mycobacterium, small or nonlipid viruses, medium or lipid viruses, fungal spores, and some bacterial spores.

Noncritical: Devices that do not ordinarily touch the patient or touch only intact skin. These devices should be cleaned by low-level disinfection. Examples include stethoscopes, blood pressure cuffs, and pulse oximetry probes.

Anesthesia Turnover

All anesthesia practitioners and technicians should be concerned with the cleanliness of their equipment, both to prevent the spread of infections between patients and to ensure that they themselves do not contract infections. Nosocomial infections (infections acquired in a health care facility) continue to be a significant drain on human and economic resources, producing suffering and higher health care costs. Infection control has become an important focus of The Joint Commission (TJC) (formerly called the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations [JCAHO]).

It is important to follow the cleaning and maintenance policies of individual machine manufacturers. Doing so can be a challenge, as recommendations vary among manufacturers.

Anesthesia Breathing Circuits

Most institutions in the United States use single-use breathing circuits that are disposed of and replaced between cases. However, in many other parts of the world, reusable circuits are used with a single-use filter to prevent cross-contamination. When reusable circuits are used, there is a risk that microorganisms may be retained in components of a circular system that could cause respiratory infections in subsequent patients. Because of this risk, bacterial filters are incorporated between the expiratory valve and the expiratory limb or between the endotracheal tube and the Y-piece. When the filter is placed between the endotracheal tube and the Y-piece, the anesthesia technician may replace the filter and leave the circuit to be reused on the next case if this practice has been approved by local institutional policy. When the filter is placed between the expiratory valve and the expiratory limb, both the circuit and the filter need to be discarded at the end of the case. Placement of a filter in the expiratory limb of the breathing circuit is commonly used to prevent contamination of the anesthesia machine. Many filters are commercially available; the two major types are pleated hydrophobic filters and electrostatic filters.

In some situations, filters are indicated for additional protection even when using single-use circuits, such as when delivering an anesthetic to a patient with known or suspected active tuberculosis (TB) or prion disease. TB is an infectious disease caused by certain strains of mycobacteria. The infection is transmitted through the air when patients with active TB infections cough, sneeze, or spit. When surgery is required in a patient with known or suspected active TB, bacterial filters should be used on the anesthetic breathing circuit. Anesthesiology personnel must also wear fit-tested respiratory devices such as the CDC-approved N95 masks. Known or suspected prion disease is another clear indication for the use of special filters and single-use breathing circuits. Prions are small proteinaceous particles that transmit infections known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. Examples of such infections include bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or mad cow disease) and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) in humans. These diseases all affect the structure of brain tissue and lead to death. There are currently no known treatments. In contrast to all other known infectious agents (bacteria, viruses, and fungi), prions contain no DNA. Therefore, they are resistant to disinfectants and sterilization techniques. Tissues at high risk of transmitting prions are the brain, spinal cord, and eye. In these cases, single-use equipment should be used whenever possible, and all reusable equipment must be quarantined after use.

Anesthesia Machine Cleaning

Machine surfaces should be decontaminated between cases. It is not necessary to regularly decontaminate the internal components of the anesthesia machine, including the vaporizers, flowmeters, gas outlets, and valves. However, components of the ventilator, including ventilator tubing, unidirectional valves, and bellows, should be cleaned or changed according to manufacturer specifications (Fig. 47.5).

FIGURE 47.5. Anesthesia machine breathing system removed from machine and ready for disinfection and sterilization by clinical technology staff.

Anesthesia Equipment Cleaning

To prevent cross-contamination between cases, all reusable equipment must be decontaminated, and all single-use items should be disposed of after use. Single-use items may include oral and nasal airways, endotracheal tubes, supraglottic airways, face masks, oxygen tubing, and breathing circuits. Always refer to the manufacturer instruction for guidance in determining the intended use of an item.

Anesthesia Work Area and Auxiliary Part Cleaning

All surfaces of monitors, ventilator controls, flowmeter knobs, vaporizer controls, blood and fluid warmers, machines, carts, cabinets, drawers, handles, touch screens, and any other work areas should be decontaminated between cases. Because porous surfaces are difficult to properly disinfect, surfaces in the operating room should be nonporous. Reusable monitors and probes, and anything that could come in contact with a patient’s skin, respiratory tract, or bloodstream must be disinfected between patients. These include, but are not limited to, blood pressure cuffs, ECG cables and leads, pulse oximeters, temperature probes, stethoscopes, and all noninvasive cables. When cleaning electronic equipment and computers, manufacturer instructions should be followed, as exposure to certain chemicals (even water) may damage these devices.

There is pressure for efficient operating room turnover between cases; consequently, an anesthesia technician does not have extra time to decipher whether items are clean or contaminated. In the operating room, all used equipment should be considered contaminated whether or not there is visible evidence of contamination.

Each institution should have a practice in place whereby anesthesia providers and technicians can walk into the operating room and know immediately what is clean and what is contaminated. This plan could include designation of a “clean” space where unused drugs and instruments are kept and a “dirty” space where all used equipment is placed. For instance, the top of the anesthesia machine would be considered contaminated, while all equipment on top of the anesthesia cart might be considered clean.

Laryngoscope Blade and Handle Management

All health care personnel must adhere to standard infection prevention and control recommendations and processes. Standard precautions must be followed, including the use of appropriate personnel protective equipment (PPE) while handling clean or soiled blades and handles.

Laryngoscope blades and handles are now available in both reusable and disposable forms, each with a different handling process. Institutions balance quality and costs of disposable items versus processing costs of reusable items for many devices; laryngoscopes are only one area in which the workroom manager must make this decision. It is recommended that institutions have designated containers for used laryngoscopes (and other reusable devices) to prevent these items from cross-contaminating clean items.

Reusable Laryngoscope Blade and Handle Management

Instruments such as reusable laryngoscopes that require high-level disinfection and sterilization must be pretreated at the point of use, before they are transported to the reprocessing area or soiled utility area. Removing visible bioburden immediately after a procedure is a critical first step in the processing of all laryngoscope blades and handles.

In some institutions, the designated technician or provider will remove the batteries from the soiled handle, and secure the battery housing, before placing the handle in the biohazard bags. Batteries are then stored in a clean location; soiled blades and handles are placed in a biohazard bag and sprayed with a pretreatment solution. The technician then transports the bag to the soiled utility area, removes the items, and places them into separate containers assigned for soiled blades and handles. The technician should follow the hospital or departmental protocol for transportation. Finally, the soiled blades and handles are transported to the Central Sterile Processing Department where they will be cleaned and sterilized with the appropriate sterilization method. When blades have been sterilized, they can be returned in sterile packs or placed in clean bags to maintain cleanliness, depending on the institution’s policies. The technician or provider should check the integrity of all cleaned blades and handles before use.

Disposable Laryngoscope Blade and Handle Management

Before assembling a disposable laryngoscope, open the packages of the desired blade and handle and verify that they are usable or good for use. Once used, the device should be disassembled (if a reusable light source or monitor is used) and the single-use blade discarded. If both the light source and blade are disposable, discard both. If a reusable light source is used, wipe it down with a manufacturer-recommended solution or wipe. Use alcohol wipes to clean the tip of the light source.

Anesthesia Drug Management

Vials and syringes of medications are intended for use in only one patient and should not be used for multiple patients. Several incidents of serious infections transmitted between patients have been traced to the use of medication vials that were inappropriately used for multiple patients. Dispose of any opened vials or syringes of medications between cases. Each hospital will have a unique policy for disposal of controlled substances such as opioids, benzodiazepines, ketamine, and others. Because these medications have high potential for abuse, their use is closely tracked. These drugs usually need to be disposed of by the anesthesia provider who checked them out from the pharmacy, and they are often placed in a closed container. (See “Returning and Wasting Controlled Substances” below, as well as Chapter 34, Medication Handling.)

Without proper accountability, controlled substances may be wasted, improperly returned, or diverted for personal use. The impact may seem minor or insignificant, yet the potential for harm is great. Both patients and health care professionals can be harmed: patients when they receive inadequate care, the wrong medication, or risk exposure to contamination; health care professionals who risk loss of employment, the effects of addiction, and jail or prison; and the hospital, which faces fiscal consequences, a damaged reputation, and/or lawsuit. Ten to fifteen percent of health care workers of all fields are estimated to have engaged in substance abuse of some kind.

Ensuring Accountability

Always obtain controlled substances in a patient-specific manner. Only remove the current dose of the medication for the assigned patient; never remove controlled substances under the room number.

After obtaining a controlled substance, maintain direct control of that substance until it is administered, wasted, or returned to storage with a witness. If necessary, the chain of custody can be transferred to another licensed staff member. Properly document within the medical record all medication administrations, as well as each transfer of custody.

Lastly, never leave controlled substances unsecured. Return unused substances and waste partially unused substances according to hospital policy. Do not loan an ID badge or password to anyone. Resolve and report discrepancies promptly per hospital policy.

Returning and Wasting Controlled Substances

All return and waste transactions must have a witness. Per the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), a suitable witness must be registered or authorized to accept controlled substances. Examples include nurses, anesthesia providers, and pharmacists. The controlled substance being wasted should be labeled with the medication name. A witness to a return should always watch the return to the return bin (the drop box). The witness should also always watch the disposal of the medication.

Properly Returning Controlled Substances

Unopened vials should be returned to the designated receptacle by a licensed provider and include a transaction receipt when returning medications in the drop box. If any controlled substances in either unopened vials or syringes are discovered by the anesthesia technician during room turnover, the technician should immediately alert the anesthesia provider in the room or the operating room pharmacist if the anesthesia provider is not available.

Noncontrolled Drug Management and Disposal

Always follow manufacturer and institutional guidelines for proper disposal of vials. Many institutions recommend that vials be thrown away at the end of the case. This practice is an added step to help providers accurately record what medications were used during the case and is useful if an adverse reaction occurs, as the lot number of a specific medication can be identified. Certain medications are packaged in glass ampules, and these should be disposed of in a sharps container to avoid injury. Always maintain a clean work area, wear gloves, and clean up any used syringes and vials. Needles should always be disposed of in sharps container. Any open syringes found between cases that still contain drugs should be disposed of per hospital policy to avoid inappropriate use by any individual or reuse on another patient.

Anesthesia Gas Management and Disposal

Anesthetic gases should be treated as drugs with a potential for misuse. Empty bottles should be disposed of or recycled according to manufacturer and institutional guidelines. They should be stored in a secure location to avoid potential misuse or improper handling by personnel.

Handling and Disposal of Sharps

A sharp is any object that could cut or puncture the skin, such as a scalpel, needle, or broken glass. Health care workers should keep handling of sharps to a minimum. Anesthesia personnel are at risk of occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus, by accidental injury from a contaminated needle or other sharps. All anesthesia personnel should use alternative needleless systems whenever possible and use devices with safety features when available. Some safety features include retractable needles, self-resheathing needles, and hinged recap needles.

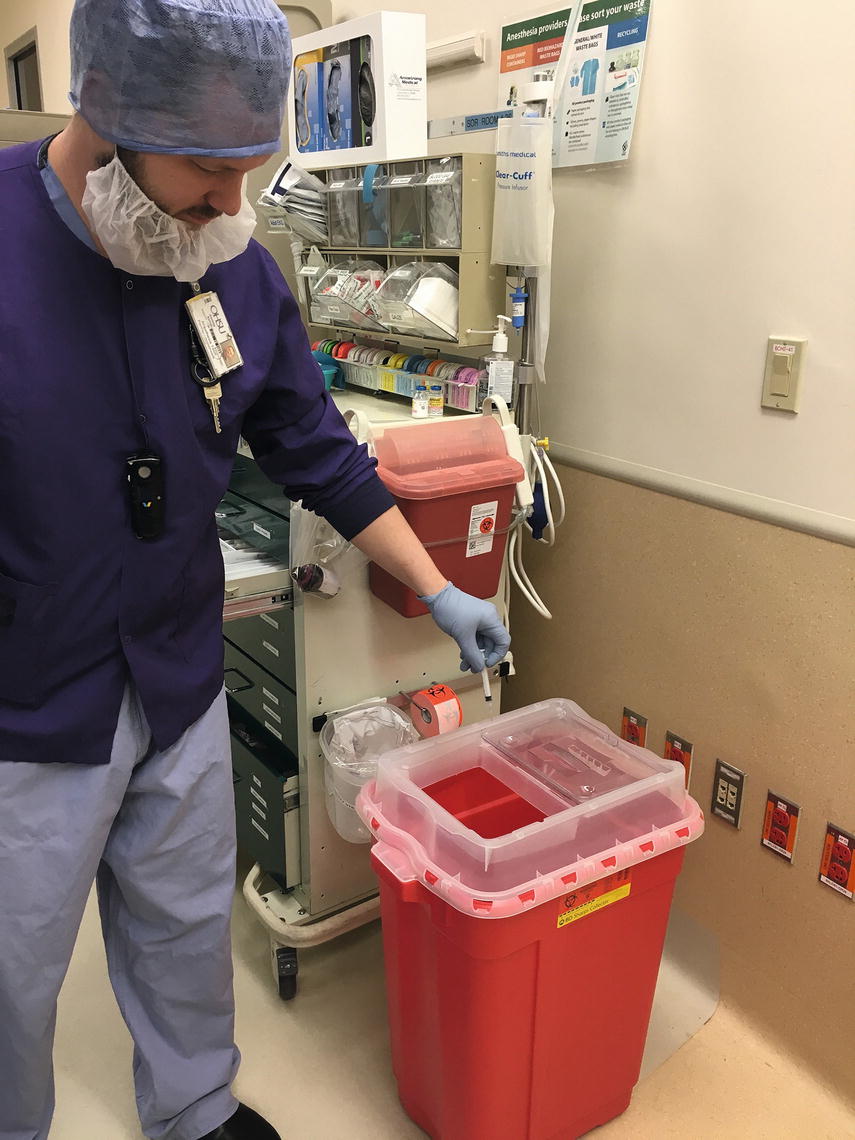

When sharps must be used, it is imperative to follow safety precautions in order to prevent needlestick injuries. Needles should never be recapped. Always be aware of the location of other staff members in the area to avoid injuries to a coworker. Be sure to use clear communication when using or transporting sharps. If a sharp is dropped on the floor, an instrument should be used to recover the sharp rather than simply using one’s hand. Anesthesia technicians may be asked to assist with looking for an object that has been placed in the trash inappropriately. Extreme care should always be exercised whenever handling trash, as a sharp may have been inadvertently placed in the wrong container. Many recommend using an instrument, such as disposable forceps, for sorting through the trash. The anesthesia technician often also assists with or participates in disposing of equipment and trays that contain sharps. Sharps are to be disposed of in leak-proof, puncture-resistant containers that are accessible to all personnel. Containers should be sealed and disposed of when two-thirds full. Be sure that the container is properly sealed before handling or transporting it (Fig. 47.6).

FIGURE 47.6. Disposal of sharps (sharps container). Notice there are two sizes available, one for small needles and one for larger sharps such as A-line kits and wires.

Waste Management and Disposal (Solid Waste, Medical Waste, Recycling, and Reprocessing)

It is estimated that operating rooms are responsible for 20%-30% of total hospital waste. The increasing use of disposable, single-use equipment accounts for a large portion of the waste, as does packaging material used to maintain the sterility of equipment. Several different types of waste are generated in operating rooms, including solid waste, medical waste, recyclable waste, medications, and sharps. Properly segregating waste into the appropriate bins can result in cost savings and environmental benefits. For example, the disposal costs for sharps bins can be several times the disposal cost for general trash. Similarly, it is up to 10 times more costly to dispose of biohazard waste than it is to dispose of noninfectious waste. Consequently, filling sharps bins and biohazard waste containers with inappropriate trash drives up the cost of waste management. Several organizations regulate the handling and disposal of medical waste, including The Joint Commission and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Over the past few years, recycling programs have started integrating into operating rooms across the country. Recycling bins are being placed in operating rooms and other perioperative areas as space allows. Bins for recycling glass are placed near anesthesia carts so that providers are able to recycle intact glass vials instead of placing them in sharps containers. Some institutions have programs to recycle uninfected paper, polypropylene, polyethylene, and polyvinyl chloride, which account for much of the packing material for anesthesia and surgical equipment. Posting signage in the operating room to remind staff of the appropriate container for different kinds of waste helps compliance. Regulated medical waste, also known as “infectious medical” waste or “biohazardous” waste, must be separated from general waste and discarded in an appropriately labeled biohazardous waste container. Regulated waste includes intravenous tubing used to administer blood products, contaminated PPE, syringes, and objects that are soiled with blood, body fluids, or PIMs.

Reprocessing

Many single-use items can now be reprocessed instead of discarded. Reprocessing bins can be found in the operating room as well as in recovery areas. Items that can be reprocessed include single-use pulse oximetry probes, sequential compression sleeves, laparoscopic and orthopedic equipment, and electrophysiology catheters. Reprocessed items are cleaned, sterilized, and quality tested by FDA-approved, third-party reprocessors and purchased back by hospitals at a reduced cost. Reprocessing results in both a significant reduction in waste and cost savings to an institution.

Summary

It is important to observe local, state, and federal regulations, as well as your own hospital policies, regarding appropriate disinfection of anesthesia equipment and handling of waste products. Further, the WHO provides principles for the safe management of hazardous waste that are applicable internationally. Waste reduction through proper segregation of trash, recycling, and reprocessing is becoming an important trend in health care, and the anesthesia technician can play an important role in these initiatives. In sanitation, just as in every aspect of your work, safety is paramount. If you always keep in mind the safety and well-being of patients, yourself, coworkers, the community, and the environment, you will be a successful anesthesia technician.

Review Questions

1. The following is an example of a critical item, according to the Spaulding classification system:

A) Laryngoscope blade

B) Pulse oximeter

C) IV catheter

D) Nasopharyngeal airway

E) None of the above

Answer: C

IV catheter: A critical item includes a device that enters normally sterile tissue or the vascular system or through which blood flows. Such devices should be sterilized, which is defined as the destruction of all microbial life.

2. Which of the following is the process that kills all bacterial life forms including spores?

A) Disinfection

B) Sterilization

C) Decontamination

D) Sanitation

E) All of the above

Answer: B

Sterilization is the only process capable of destroying all microbial spores. Autoclaving, using a hot air oven, or using a chemical sterilant can accomplish sterilization.

3. Cleaning is important as a first step because

A) It removes physical debris and bioburden before any other part of the decontamination process

B) Cleaning of disposable items before discarding reduces the waste stream

C) Cleaning destroys microorganisms

D) Cleaning is unnecessary if an item will be undergoing sterilization

Answer: A

Cleaning is the physical process that removes organic or inorganic debris (bioburden), such as retained salts and organic soil, from inanimate or animate objects. It is the first step in the decontamination process. Soil can damage sterilizer equipment. Residues may interfere with the device function even after sterilization. Reducing the waste stream is important but is accomplished through proper sorting of waste and reusables rather than cleaning of waste items before disposal. Initial destruction of microorganisms is decontamination.

4. From which of the following patients should used anesthesia equipment be considered contaminated, regardless of whether or not there is visible evidence of contamination?

A) Patients with hepatitis C

B) Patients with prion disease

C) Patients with TB

D) Patients with isolation orders for transmission-based precautions

E) All patients regardless of infectious disease states

Answer: E

All used anesthesia equipment in the operating room should be considered contaminated whether or not there is visible evidence of contamination and regardless of patient condition.

5. What should you, the anesthesia technician, do if you discover a controlled substance during a room turnover and the anesthesia provider is unavailable?

A) Immediately alert the operating room pharmacist.

B) Wait for the anesthesia provider.

C) Obtain a witness and return the controlled substance yourself, properly documenting the process.

D) Try to return the substance to the anesthesia team that was in the room before you.

E) Waste the substance per hospital policy.

Answer: A

If you discover any controlled substance in either unopened vials or syringes during room turnover, you should immediately alert the anesthesia provider. However, if the anesthesia provider is not available, you should immediately alert the operating room pharmacist. Controlled substances must usually be returned by the anesthesia provider under supervision of a witness (nurse, anesthesia provider, pharmacist). Do not attempt to return the substance without instruction to do so. Do not wait before alerting someone, as you may forget about the presence of the controlled substance. Do not waste the substance and do not try to return the substance to the anesthesia team that used the room prior to you.

6. You have a pulse oximetry probe that needs to be cleaned after use. What Spaulding decontamination category is this device in, and what level of cleaning is required?

A) Noncritical, high-level disinfection

B) Semicritical, high-level disinfection

C) Noncritical, low-level disinfection

D) Semicritical, low-level disinfection

E) Semicritical, sterilization

Answer: C

Devices that do not ordinarily touch the patient or touch only intact skin, such as a pulse oximetry probe, are noncritical objects that require low-level disinfection. Semicritical devices require high-level disinfection and are devices that come into contact with intact mucous membranes and do not ordinarily penetrate sterile tissue. The third category in the Spaulding classification system is critical devices, which are devices that enter normally sterile tissue or through which blood flows and which require sterilization.

7. It is inappropriate to reprocess which of these items?

A) Electrophysiology catheters

B) Intravenous tubing

C) Single-use pulse oximetry probes

D) Sequential compression sleeves

E) Orthopedic equipment

Answer: B

Reprocessed items include single-use pulse oximetry probes, sequential compression sleeves, laparoscopic and orthopedic equipment, and electrophysiology catheters. These items are cleaned, sterilized, and quality tested by FDA-approved, third-party reprocessors and are purchased back by hospitals at a reduced cost.

SUGGESTED READINGS

DEA regulations for destruction of controlled substances. 2014, September 9. Available from: https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/cfr/1317/subpart_c.htm. Accessed February 19, 2018.

Dorsch JA, Dorsch SE. Understanding Anesthesia Equipment. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2008.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing needle stick injuries in health care settings. 1999. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2000-108/pdfs/2000-108.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2018.

Rutala WA, Weber DJ; The Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2008. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/pdf/guidelines/disinfection-guidelines.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2018.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Selecting, evaluating and using sharps disposal containers. 1998. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-111/. Accessed February 19, 2018.

World Health Organization. Healthcare waste management. 2005. Available from: http://www.healthcare-waste.org/en/115_overview.html. Accessed February 19, 2018.