CHAPTER 56

Simulation-Based Training

Introduction

“I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.”

—Confucius

Less than one minute after takeoff, on January 15, 2009, US Airways flight 1549 struck a flock of geese and lost power to both engines. Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger immediately reported to air traffic control: “This is Cactus 1539, hit birds. We lost thrust in both engines. We’re turning back towards LaGuardia.” Sully soon realized that they did not have the elevation or the time to make it back to the LaGuardia airfield, and he made the strategic decision to glide the commercial airliner onto the Hudson River. After landing the aircraft safely on the river with everyone aboard relatively unscathed, many labeled the incident “The Miracle on the Hudson.” In fact, it was no miracle that Sully and his flight crew had the experience and skills to perform the nearly impossible maneuver; it was partly due to countless hours logged behind the controls of a flight simulator and years of Crisis/Crew Resource Management (CRM) team training. When singled out for praise after the incident, Sully emphasized that all the members of the flight crew came together as a highly functioning team, without which the situation might have turned out disastrously.

In the aviation industry, flight simulations replicate reality so closely that all commercial pilots, regardless of experience, are required to practice simulated flight training every year of their career. Much like the aviation industry, health care simulations aim to increase practitioners’ effectiveness and proficiency, gather data about how systems respond to various situations, and increase the efficiency and safety of the services delivered (Fig. 56.1).

FIGURE 56.1. High-fidelity patient simulator.

By simulating real patient interactions, imitating anatomic regions and clinical tasks, and mirroring real-life clinical situations, medical simulation can enhance the education of technical, behavioral, and teamwork skills. The modern-day health care simulation center shares the same fundamental purpose as yesterday’s skills laboratory: to practice and refine skills in an effort to improve proficiency and patient safety. A fully functional simulation center also adds the capacity to fully immerse teams for CRM team training. Modern simulation training tools are high-fidelity (allowing for an accurate life-like reproduction of clinical situations) and high-technology tools, which are revolutionizing the way in which we learn and refine many of our skills in our rapidly advancing health care field.

Simulation in Health Care

In health care, the simulation training tool that is analogous to the flight simulator is the modern life-size human patient simulator. These human simulators are of such high fidelity that they have pulses at multiple anatomic locations, audible breath sounds and heart tones, pupils that dilate, arms for placement of vascular catheters, and an airway that can replicate varying degrees of difficult airway situations. Highly technical learning tools like human simulators have an established role in simulation education, but they may not be available at all facilities or are they fitted to all training tasks. Valuable simulation-based education does not have to be high fidelity for it to be an effective training tool. ATs already use simulation in their education. For example, practicing on equipment while it is not in use is a form of simulation, as is basic life support (BLS) training on a Resusci AnneTM mannequin. There are many opportunities for the AT to use a variety of simulation tools to improve important technical and behavioral skills, for example, a surgical towel (low fidelity) to practice suturing arterial line equipment, a simulated tibia model (moderate fidelity) to practice intraosseous cannulations, or a simulated patient interaction (high fidelity) that can assist with communication training. Although modern advances in technology have increased the fidelity and accessibility of simulators in health care, neither high technology nor high fidelity is necessary for real learning to occur.

Anesthesia Technicians and Simulation

There are many tasks that the AT performs that directly affect the quality and safety of patient care, whether diagnosing a problem with the anesthesia machine, assisting the anesthesia provider during a sterile procedure, or performing quality chest compressions during an intraoperative cardiac arrest. Many procedures in anesthesia require strict sterile technique and safe practices whenever sharps such as needles and scalpels are being used. In a controlled, learner-focused simulation environment, an AT can simulate important tasks such as proper sterile glove technique, maintenance of equipment tray sterility, and safe sharps disposal. Perfecting sterile technique and sharps safety is imperative before attempting these skills in reality. Breaking sterility and accidental needle injury risk real infection in the patient and the provider. In the simulation setting, these skills can be refined without those risks.

As pointed out above, successful outcomes in a complex crisis depend less upon the actions of one individual and more upon the coordinated actions of a team. ATs are critical members of most crisis response teams in the operating room. Their assistance may be required for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, vascular access, or dealing with a difficult airway. The role of the AT during a crisis should not be underestimated. ATs should advocate for participation in all team training events or simulations that involve operating room personnel. When was the last time ATs in your department participated in a simulated emergency with operating room personnel?

Simulation Environments

Simulation training can be conducted in many different environments. There are dedicated simulation centers with rooms outfitted to replicate an operating room environment, complete with anesthesia machine and monitors (Fig. 56.2). However, with the advances in simulator technology, wireless life-sized human patient simulators can now be taken out of the simulation centers into the actual clinical setting, giving the simulation participants the advantage of familiar surroundings and resources. This type of “in situ” simulation provides a potent learning experience and may make simulation mannequins and task trainers more accessible to ATs. Virtual reality simulation (e.g., virtual anesthesia gas machine http://vam.anest.ufl.edu/simulations/vam.php) and mobile simulation are growing, aiming to bring high-fidelity simulation experiences to health care learners and professionals in out-of-hospital and rural communities.

FIGURE 56.2. Interdisciplinary anesthesia team training during a simulated crisis scenario.

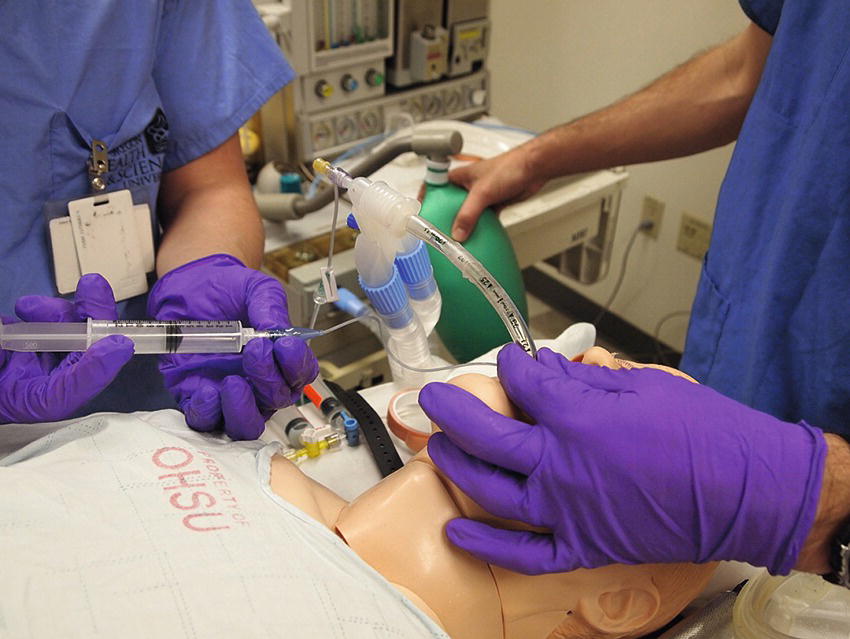

Training during actual patient care can be difficult. During simulation training, the focus can be placed on the learner and their performance, whereas in the clinical setting, the primary duty is to the patient and their safety. Another advantage to simulation training is that we can take a “time out,” suspend time, or have a do-over, luxuries that are not provided in the clinical setting. During simulations, the learner can be allowed to make mistakes to see the consequences of their decisions. With simulation, the practitioner can repeatedly perform tasks on a model in a controlled and safe environment until gaining the necessary confidence, competence, and proficiency to safely perform the procedure. For example, an anesthesia resident can practice the steps involved in anesthesia induction and intubation multiple times before performing a supervised anesthetic on a patient (Fig. 56.3).

FIGURE 56.3. Anesthesia induction simulation training.

CRM

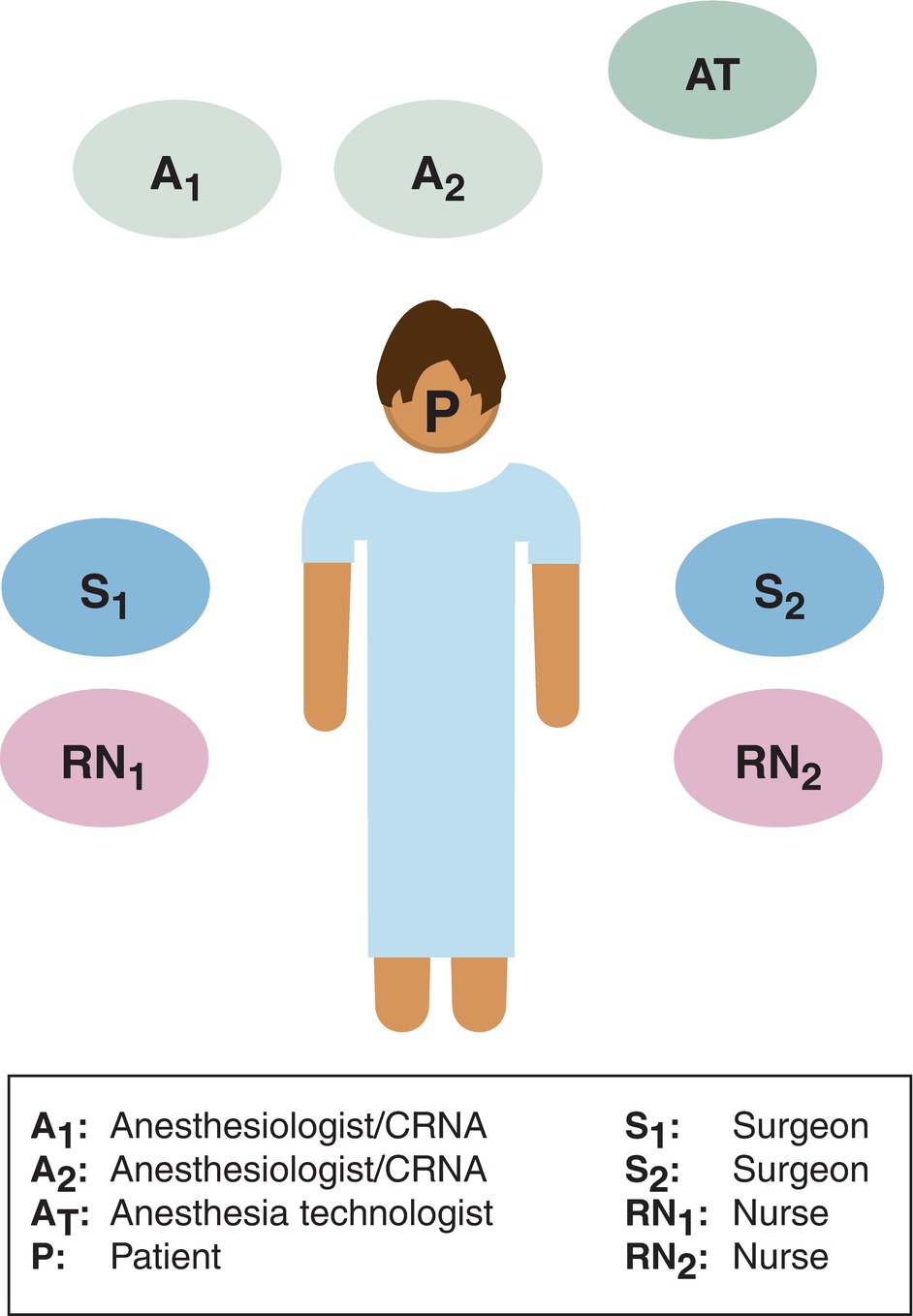

Operating room team members, including ATs, need to have the ability to consistently function as members of a team, whether in day-to-day activities or during a crisis. There are many technical tasks, communication, and teamwork behavioral skills relevant to ATs that can be practiced by using simulation to promote patient safety. CRM provides a formal framework for teaching and evaluating critical communication and teamwork behaviors that foster team cohesion and error reduction (Fig. 56.4). As noted earlier, the AT is an integral part of the anesthesia patient care team. As such, they play an important role in the larger interdisciplinary operating room team.

FIGURE 56.4. Crisis resource management simulation debriefing. Simulation not only teaches and practices communication and teamwork but helps participants reflect on their own behaviors.

Although not emphasized in most health care curricula, team training is a concept that focuses on human behaviors, teamwork, communication, and crisis management. CRM training began initially in the military and the aviation industry but is becoming increasingly emphasized in anesthesia practice as studies show that the behavioral components of crisis management can impact patient outcomes, positively or negatively. CRM skills, when used properly, lead to clear, deliberate communication between all team members, thus minimizing potential errors and confusion. Simulation provides an excellent opportunity for health care team members to hone these team skills and receive feedback and practice improvement suggestions outside of the patient care setting.

CRM defines certain key behavioral skills to improve team interactions and minimize errors. Recognition of one’s own role responsibilities within the team as well as other team members’ responsibilities allows the team to bypass the organizational part of team building straight into task delegation. Each operative team member has certain specific role responsibilities, which are clearly defined and well recognized. For example, the anesthesiologist will manage the patient’s airway and anesthetic drugs; the scrub tech will organize the sterile field and assist the surgeon; and the AT will assist the anesthesia provider under their expert direction. The ATs role responsibilities are broad, and like most members of the operating room team, their job description varies greatly from day to day, from nonemergent to emergent cases, and from the expected to the unexpected. This requires extreme on-the-job flexibility while maintaining the highest standards of professionalism. CRM behavioral skills emphasize the importance of deliberate and clear communication during a crisis. These types of skills can be practiced during CRM simulation training in an effort to refine communication skills, an area in which many studies have shown to be a major source of errors in all complex systems.

In general, the AT needs to be oriented to the clinical situation or have clear “situational awareness.” This means that the AT needs to be able to understand the etiology of the unfolding crisis in order to anticipate the next necessary equipment (e.g., code cart, difficult airway cart) or task (e.g., arterial blood gas, cell saver). If the AT is unclear as to the situation, then they are not able to function at their highest capacity by initiating the next step to avoid worsening of the crisis. In a very real way, the members of the operative team and especially the anesthesia providers are responsible for orienting the AT to the situation. However, team training emphasizes each team member’s responsibility to actively seek out the information that they are missing. In other words, if not given, it is the AT’s responsibility to ask for additional clarification regarding the situation, so that they can assist in the best way possible. For example, the AT may have more information than any other member of the anesthesia team about equipment logistics: Is the rapid infusion device currently available? Where is it stored? How long will it take to set up?

Another CRM skill closely related to situational awareness is “error anticipation.” If a potential error can be identified or anticipated before it even occurs, patient care becomes safer and more efficient.

Usually, the AT is supporting more than one OR during normal elective cases. When a crisis develops, priorities change. An important part of CRM is learning to allocate resources and responsibilities during a crisis: “resource allocation.” Allocation of resources refers not only to equipment but also to all the human resources that are immediately available. Equipment resource allocation is relatively easy to understand: you either have the piece of equipment you need in good working order or not. In terms of human resources, it is easy for one person to get overwhelmed with assigned tasks during an evolving crisis, so proper resource allocation helps to spread tasks out among team members. If overwhelmed with immediately necessary tasks, the AT needs to ask for an additional AT for assistance or, if none is available, for help from the anesthesia provider with task prioritization. This latter approach carries the additional benefit of clearly letting the anesthesia provider know of the resource constraints. Resource allocation for the AT includes an organized familiarity with the resources available: if one fiberoptic bronchoscope breaks down, where is the next closest available scope? If an AT is busy assisting with a crisis in the operating room, is there another available AT to assist in another room? Are the other ATs on duty aware of the unfolding crisis and are they available to assist if necessary? Is there another AT who is on call from home, who could be called in and arrive in a time frame that would be helpful during the crisis? At times, an AT is not able to manage all the required tasks in a safe and timely manner; therefore, it is important to recognize limitations and call for assistance. All of these issues need to be addressed either before or early on during the evolving crisis in the operating room.

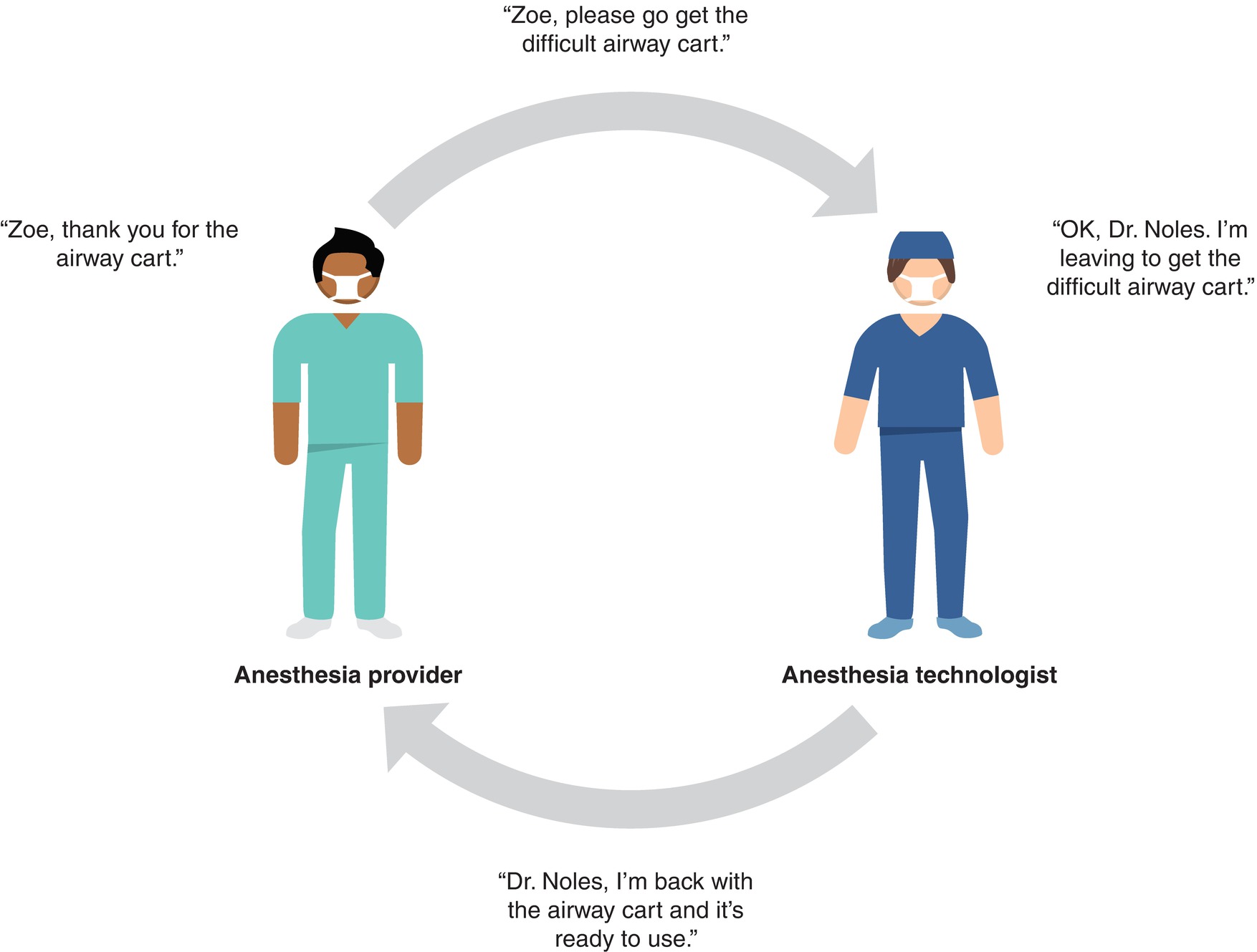

Of all the CRM skills, none is more important than communication. It may seem obvious, since we communicate every day, but deliberate communication with an emphasis on clarity of thought is actually challenging, even more so in a crisis. Behavioral communication strategies such as directed communication, closed loop communication, and transparent thinking are learned skills, which make communication more clear and efficient. “Directed communication” refers to addressing questions, concerns, or orders to a specific person, as opposed to giving orders to “somebody” (“somebody get the difficult airway cart”). Indirect communication sets the stage for errors of omission (“I didn’t get it, I thought you were talking to someone else”) or commission (“we both went to get it, we both thought you were talking to us”): neither is an efficient use of resources. In large institutions, operative teams may be made up of people who have not worked together before or who have never been formally introduced. It may be much more difficult to remember everyone’s names, especially in a crisis. Eye contact, pointing, or calling on team members by their role (“surgeon,” “circulator,” etc.) are alternative means of directed communication (Fig. 56.5). If a member of the team is using indirect communication, clarify first rather than carry out the task, especially if you have other tasks lined up. The AT might proactively say, “Shall I get the blood gas or the blood products first?” “Closed loop communication” refers to team members acknowledging a request and reporting back when the task is accomplished (Fig. 56.6). This is a simple maneuver that makes a big difference to the team leader by allowing them to focus on another task/problem, knowing that you will report back when you have accomplished your assigned task. Another aspect of closed loop communication is providing feedback to another team member. One common source of communication errors is medication handling. When an anesthesia provider has asked for a particular drug over the phone, one way to help minimize drug errors or delays is to close the loop of communication by verbally reconfirming all relevant drug details before getting off the phone: drug, dose, preparation (drip or vial), and, importantly, patient name. For example, an anesthesiologist calls into the AT workroom and asks for an amrinone infusion. The AT repeats back the request, “OK, an amrinone infusion.” Upon hearing the feedback, the anesthesiologist realizes he or she meant to ask for an amiodarone infusion and can correct the error.

FIGURE 56.5. Operating room CRM team model. The operating room team is highly structured by role. Team members should know one another by name. However, if this is not the case, role clarity is very helpful in assisting with task assignment and closed loop communication.

FIGURE 56.6. Closed loop communication.

Closed loop communication also refers to nonverbal communication. For example, when bringing a laboratory result or requested piece of equipment to the operating room, use eye contact or direct verbalization to ensure the anesthesia provider sees the results or equipment and has a chance to acknowledge it and make additional requests prior to leaving the room. “Transparent thinking” by teammates helps each team member share the same mental model of what is happening (situational awareness), thus allowing everyone to anticipate the next probable event or task and to provide information regarding their tasks and their observations. The anesthesia technician announces, for example, “I’m drawing a blood gas” in a critical situation, knowing that many eyes may be on the arterial line tracing. The AT should also speak up if observing an unsafe condition or something the team leader may be unaware of. All operative team members should be alert to potential communication errors. CRM behavioral skills emphasize the importance of deliberate and clear communication during a crisis. These types of skills can be practiced during CRM simulation training in an effort to refine communication skills, an area multiple studies have shown to be a major source of errors in complex systems.

Summary

Anesthesiology has been a leader in advancing simulation training in health care by utilizing it to practice complex technical skills and interdisciplinary team training in an effort to improve patient safety and promote efficient delivery of health care services; see APSF at http://www.apsf.org/. Anesthesia technology is a field in which there are a tremendous number of technical and behavioral skills that must be mastered to be a strong member of the operating room team. ATs are critical members of that team and should advocate within their own departments to participate in simulation and operating room team training. The operating room team shares many characteristics with other high-stakes industries in complex environments in which errors occur. Simulation helps to build teams that are highly functional, well prepared, and able to prevent errors.

Review Questions

1. Which of the following is not an example of simulation training in health care?

A) Using an orange to practice intramuscular injections

B) Visualizing the steps involved in a paramedian epidural catheter placement before actually performing the procedure

C) Using a tibia model for practicing intraosseous catheter

D) Using virtual reality to perform the anesthesia gas machine checklist

E) All of these are examples of simulation training in health care

Answer: E

All of these are examples of simulation training in health care. Anything that involves practice before a procedure or task is performed on a real patient can be considered simulation training. This may include mental or physical rehearsal for a difficult procedure before performing the actual task, using a specialized task trainer model and using a screen-based computer model or a high-fidelity virtual reality environment such as a medical simulation center.

2. During a training session at the simulation center, the anesthesia technician is assisting the anesthesia provider with the positioning of a standardized live patient actor for an epidural placement. This is an example of ________fidelity and _______ technology simulation.

A) high, high

B) low, low

C) high, low

D) low, high

E) This is not an example of simulation because it is being conducted with a real patient actor.

Answer: C

This is considered high fidelity because the patient actor replicates a real patient very closely, but low technology because humans aren’t considered technology. Human patient actors are frequently used to practice health and physical skills, communication skills, and team training.

3. During an anesthesia crisis resource management simulation training, the anesthesia technician states, “Somebody get me a code cart.” This is an example of …

A) Error anticipation

B) Closed loop communication

C) Directed communication

D) Indirect communication

E) Resource allocation

Answer: D

This is an example of indirect communication, which is when the statement, question, concern, or order is not directed to a specific person. Error anticipation is when an error is identified or anticipated before it occurs; closed loop communication refers to team members acknowledging a request and reporting back when the task is accomplished; directed communication refers to addressing questions, concerns, or orders to a specific person; and resource allocation refers to organizing the resources available, whether it’s equipment or personnel.

4. Team members who all share a mental model of evolving clinical circumstances share:

A) Situational awareness

B) Closed loop communication

C) Directed communication

D) Indirect communication

E) Transparent thinking

Answer: E

Transparent thinking is when team members share a mental model of an evolving clinical situation. Situational awareness is when an individual has an understanding of the etiology of the unfolding crisis; closed loop communication refers to team members acknowledging a request and reporting back when the task is accomplished; directed communication refers to addressing questions, concerns, or orders to a specific person; and indirect communication is when a statement, question, concern, or order is not directed to a specific person.

SUGGESTED READINGS

Eisen LA, Savel RH. What went right: lessons for the intensivist from the crew of US Airways flight 1549. Chest. 2009;136:910-917.

Flanagan B, Clavisi O, Eppich W, et al. Simulation-based team training in healthcare. Simul Healthc. 2011;6:S14-S19.

Scalese RJ, Obeso VT, Issenberg SB. Simulation technology for skills training and competency assessment in medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;23(suppl 1):46-49.