OLD GHOSTS AND ANCIENT TONES

There are things that are part of the landscape of human life that we all deal with—the joy of birth, the sorrow of death, a broken heart, jealousy, greed, envy, anger. All of these things are what is in music. Because it is the art of the invisible. There’s a truth in the music. And it’s too bad that we as a culture have not been able to address that truth. That’s the shame of it…. The art tells more of the tale of us coming together.

—WYNTON MARSALIS

IT MAY BE APOCRYPHAL, but we’ve stumbled across the anecdote from enough sources and in enough different places to satisfy any journalist’s or historian’s prickly conscience and ethical obligation. The late music critic Nat Hentoff first told us the story more than two decades ago when we were making a television series for public broadcasting on the history of jazz. Then, years later, working on this project, a history of country music, Marty Stuart, the unofficial historian and keeper of all things sacred about the music he loves, related the same tale to us. It seems that Charlie Parker, one of the great creative forces in jazz (and, with Dizzy Gillespie, the “inventor” of the hugely complex, fast-paced, dazzlingly virtuosic variety of jazz called bebop), was between sets at one of the clubs he played at on Fifty-Second Street in New York City in the late 1940s. Much to his fellow musicians’ shock, they found him feeding nickels into the jukebox, playing country music songs. “Bird,” they asked, using his famous nickname, “how can you play that music?” Parker replied, “Listen to the stories.”

For most of the last forty years, we have made films solely about American history. We stated plainly when we were beginning our first film that we were uninterested in merely excavating the dry dates, facts, and events of American history; instead, we were committed to pursuing an “emotional archeology,” “listening to the ghosts and echoes of an almost indescribably wise past.” Eschewing nostalgia and sentimentality, the enemies of any good history, we have nevertheless been unafraid of exploring real emotion—the glue that makes the most complex of past events stick in our minds but also in our hearts. We consciously chose not to retreat to the relative safety of the rational world, where one plus one always equals two. We are most interested in that improbable calculus where one plus one equals three. That, to us, is, in part, emotional archeology.

For at least twenty years, we have often quoted the late historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who liked to say that we suffer today from “too much pluribus and not enough unum.” We have been all about “unum” for decades, extolling as much as possible a bottom-up version of our past as well as a top-down one, looking for ways to accentuate what we share in common, not what drives us apart, widening the scope of American history, not narrowing it. We wished to exclude no one’s story at a time when our tribal instincts seem to promote so much disunion.

We also began to see that our work and interests have always existed in the figurative space between the two-letter, lower-case plural pronoun “us,” and the much larger, upper-case abbreviation for our country—U.S. There is a lot of room—and feeling—in there, between “us” and U.S.—the warmth and familiarity of the word “us” (and also “we” and “our”), standing in contrast to the sheer majesty and breadth of the history of our United States. We have been mindful, too, of what the novelist Richard Powers wrote: “The best arguments in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” It is with all those references and contexts in mind—and in heart—that we have, over the last several years, devoted so much of our creative energies trying to understand country music, the art that tries to tell the stories of those who feel like their stories aren’t being told. We could not have come to it a moment sooner, but we are also glad we did not start it a moment later.

It is conventional wisdom, accepted by too many, that country music is somehow a lesser art form, a simple country cousin (literally), lacking the elegance and complexity of jazz, a suspect musical form which too often is easily relegated to the “lower forty” of our cultural studies, bottomland, not befitting the scrutiny of sophisticates and—God forbid—scholars. Much to our delight, we have, over the last eight years of working on an eight-part, sixteen-and-a-half-hour series for PBS on the history of country music, and now this companion volume, discovered just the opposite. Country music turns out to be a surprisingly broad and inclusive art form that belies the narrow definition into which many have imprisoned it. The music’s narrative arc offers a new and at times achingly personal perspective on our last turbulent century, its clarity and honesty a refreshing corrective to the recent corruptions of popular culture. It is the story, at heart, about so-called ordinary people, who many times lifted themselves out of unbelievable poverty and hardship, and following an inner ambition or a dream (or with the help and kindness of others), shared their own stories—what Charlie Parker heard—in words so powerful and heartbreaking, and in music so plaintive and moving, that they have allowed the rest of us to dream our own dreams as well. And what they have left behind (and continue to create) is a legacy of emotion, authenticity, and simplicity unmatched in American music.

It is tempting to segregate the various forms of American music into their own pigeonholes, erroneously presuming that these forms had or have little in common. But they all—whether jazz, the blues, rhythm and blues, folk, rock, or country—share a common ancestry in the American South. Within the frictions and tensions between blacks and whites trying to negotiate their stories with one another is the story of the birth of American music in general and country music in particular. Our political and social histories correctly chart the indignities and injustices these frictions and tensions often produce. Country music is not immune to those sufferings, but it does, like other forms of music, suggest happier and more transcendent possibilities, a civilized alternative that tries to get beyond those tribal impulses that continually seem to beset us. It is important to affirm that the musicians and artists themselves seek only to follow their own muse, unconcerned with categorization and labels, and so they cross and recross the restrictive fence lines, the musical boundaries we have created for our simplistic filing system. To understand these complex interrelationships, and the sublime art and emotion they promote, requires only that we heed Charlie Parker’s words: Listen to the stories.

A crowd in Backusburg, Kentucky, gathers to hear stars from The Grand Ole Opry, 1934.

Those of us lucky enough to be engaged with trying to come to terms with this utterly American music felt we had been granted a privileged glimpse into a wildly diverse American family. It is a story that quickly became our story, too. The basic constituent building blocks of our series, and now this book, are the pantheon of several dozen great country artists our narrative considers and asks the viewer and reader to get to know. From Jimmie Rodgers and the original Carter Family to Dolly Parton and Garth Brooks; from Johnny Cash and his superbly talented daughter Rosanne to Hank Williams, his son Hank Jr., and his granddaughter Holly; from the Maddox Brothers and Rose to Merle Haggard and Buck Owens and Dwight Yoakam; from Loretta Lynn and Charley Pride and Faron Young to Kris Kristofferson, Felice and Boudleaux Bryant and Roy Acuff; from George Jones and Tammy Wynette to the Louvin Brothers and Naomi and Wynonna Judd; from Emmylou Harris and Bill Monroe to Marty Stuart and Connie Smith, from Ernest Tubb and Bob Wills and Gene Autry to Willie Nelson and Earl Scruggs and Roger Miller, we felt as if we were getting to know real people—almost as if they were members of our own family. There were the black sheep and the patriarchs, the sage mentors and the stage mothers, the addicts and the orphans, the sinners and the saved, the song catchers and the wordsmiths, the lovers and the loners, all the various branches and offshoots of this complicated family that was also—amazingly—asking us in, asking us to stay for supper.

Everywhere we explored this story, we found generosity and human kindness. Her grade school teacher let little Brenda Lee, a child star and singing sensation, put her head down in class to rest from the arduous travel schedule her fame demanded of her. When Mel Tillis’s teachers recognized that he could sing without the stutter that affected him and his brother and father, they would take him from class to class, letting him sing—and starting, as he remembers, his career in show business. Lefty Frizzell brought a teenage Merle Haggard onstage with him and “gave me,” Haggard said, “the courage to dream.” Bill Monroe did the same for Ricky Skaggs…when he was only six. There were slights and indifference, too: “The human being has a history of being awful cruel to something different,” Haggard told us, as he and countless others had to escape the prejudice inflicted on them. Sometimes that pain was paradoxically the deciding factor in their success—their art came from seeing that cruelty and rising above it in songs of agony and grinding hardship.

Young Ricky Skaggs performs with his parents, Dorothy and Hobert, 1961.

In no other musical idiom had we ever come across this palpable sense of belonging to such a complex American family—the hundreds of people and their fans—who populate and animate our series. It is a hallmark of this far-reaching and sometimes dysfunctional family that once you’re in, once you’ve been accepted, you’re in for life, and that kind of loyalty and kindness, but also a good bit of inevitable tension, permeates the whole of the tale we try to tell.

In the beginning of our story, we noticed an unavoidable and in some ways welcome tension between the Old World (that is, the old Europe, which brought us the fiddle, and the old Africa, which brought us the banjo) and the New, which would “steal” and adapt and synthesize songs and instruments and attitudes, as a uniquely American sensibility was taking form, expressed so perfectly in the “hill country” music coming out of western Virginia and eastern Tennessee, the Carolinas and the hollows of Kentucky. But country music’s much revered ancestry, the “old ghosts” and “ancient tones” that Mississippian Marty Stuart invokes in an interview for our film, has had its own tensions with this new, restless, almost omnivorous musical form. In any given era, country music has always wanted to push its own boundaries, always wanted to try something else, always wanted to swallow whole this new thing or that, always wanted to move away from its roots. And then, just as forcibly, it has always wanted to move back to an earlier era, to embrace all the old traditions, all the old ghosts and ancient tones, whether they be centuries or just decades old. It was exhilarating to see this all being worked out right before our eyes: a respect for the past and a willingness to toss it aside for whatever was feeding the artistic appetite of the moment. One is reminded of Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 Message to Congress, where his country is undergoing its own almost bipolar breakup. The president’s speech careens between a respect for tradition: “Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history…. The fiery trial through which we pass will light us down in honor or dishonor to the latest generation”; to a realization that everything has to be remade, completely reinvented: “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present…. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew.” As we traveled the five score years of the arc of our film series, we saw time and time again this ferocious need to be different, and yet, almost at the same time, this passionate, deeply felt and deeply American desire to remain the same. It lit us on fire.

Those tensions extended to black and white, of course; that is the age-old American issue (Lincoln knew it); it is a tension that country music was destined to inherit at its very beginning. The Mount Rushmore of its early stars—Jimmie Rodgers and A.P. Carter, Bill Monroe and Hank Williams—all had an African-American mentor who gave them an appreciation for the blues and enabled each to be better than he was before. Country music has not spent much time focusing on that, but we found the reality of it to be resonant and deeply revealing. It runs both ways, too. Many African-American artists, like Charlie Parker, but also DeFord Bailey, Ray Charles, and Charley Pride, found in country music their own inspiration—and their curiosity and contributions broadened the music’s appeal and legitimacy.

The tension between Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, the sinner and the saved, the rascal and the responsible one, runs throughout all of American music, but no more so than in country music. Jimmie Rodgers, the music’s first superstar, Hank Williams, perhaps its greatest songwriter, and Johnny Cash, its towering, transcendent patriarch, were all familiar with the dark side, the Saturday night of dimly lit bars and too much alcohol, infidelity and other temptations of the road, and they all celebrated an outlaw streak, an exultation of the rogue, that extends from them through Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Waylon Jennings, right up to the present. On the other hand, the Carter Family seemed to embody a centuries-old ideal of Family, Mother, and the Church that runs genuinely (and sometimes sanctimoniously) through the music and the country it tries to represent. Their example would be mirrored in generations of future stars more interested in promoting virtue in their music than vice. But as is often the case, those disparate polarities coexisted within the same artist, and the profoundly human music they made as a result reflected their never-ending search for some kind of redemption. Rosanne Cash told us that her father “could hold two opposing thoughts at the same time and believe in both of them with the same degree of passion and power.” His art was the mitigating, the reconciling force. He “worked out all of his problems onstage,” Rosanne continued. “That’s where he took his best self, that’s where he took all of his anguish and fears and griefs, and he worked them out with an audience. That’s just who he was. And [he] got purified by the end of the night.” On the other side of the coin, the reality of A.P. and Sara Carter’s strained marriage and her passionate love affair with her husband’s young cousin is the stuff of almost unbelievable melodrama.

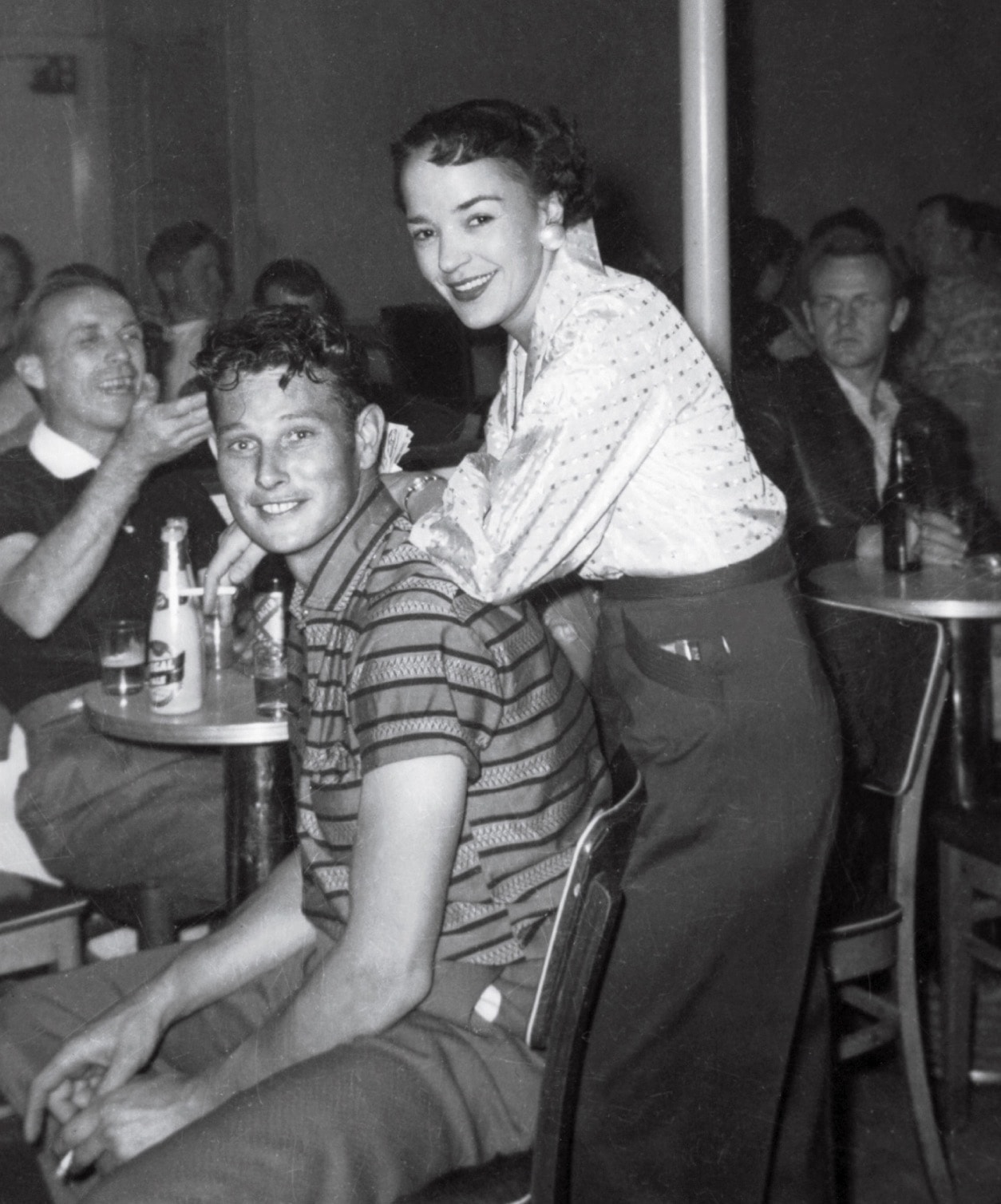

Fans at the Blackboard honky tonk have fun listening to Buck Owens and His Buckaroos, 1956.

There is in country music, as in all things, an inherent tension between men and women, but we’ve never worked on any film before now that has had such strong and assertive women, whose artistic expression of their own struggles predates any feminist or Me Too movement. From Sara Carter chafing at a distant and distracted husband, to Kitty Wells defiantly proclaiming in a number one hit, “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels”; from Loretta Lynn’s subversively proto-feminist songs “Don’t Come Home a-Drinkin’ with Lovin’ on Your Mind” and “The Pill,” to Reba McEntire’s willingness to confront enduring women’s issues in songs like “Is There Life Out There?”; not to mention the incredibly successful career of Dolly Parton; women, and their stories and art, make up a huge part of our sprawling, multigenerational, almost Russian novel–like series and this book.

More tensions central to country music continued to surface and continued to multiply as we pursued our story. Ever present was the conflict between art and commerce—that is to say, whether to be a copycat of some earlier success, or, as Garth Brooks explained to us, “go down being true to yourself.” (Spoiler: Brooks chose to be true to himself, but did not go down.) The influential singer-songwriter Guy Clark told his up-and-coming fellow Texan Rodney Crowell, “You’re a talented guy. You can be a star. You probably have the talent to do it. Or you can be an artist. Pick one. They’re both worthwhile pursuits.” Fortunately, many of the artists we meet and follow in our series end up having it both ways. But a record’s triumph always bred in the businessmen who sold them a desire to clone whatever had just worked—the death, it would seem, of creativity in any endeavor. Still, in the late 1950s and early ’60s, some record producers, hoping for crossover success in the lucrative pop market, created the Nashville Sound, smoothing out country’s rougher edges, adding sweet strings and backup vocals, and ended up having hit after hit. Chet Atkins, the genius session guitarist turned genius producer, was once asked what the Nashville Sound was. He jingled the change in his pocket.

There were also geographical tensions in a music that was never one thing, never something easily categorized or labeled. From the “ancient tones” of the hill country music springing out of the farmhouses and hamlets of Appalachia to the rough, wide-open songs of California’s Central Valley, country music has absorbed—and, for the most part, tamed—all its many and varied constituent parts. The Deep South gave us the mournful blues and aching heartbreak of Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Williams (along with a huge dollop of hell-raising fun), and Texas and Oklahoma supplied dozens of defiant, fiercely independent singer-songwriters, all willing to buck traditions imposed from on high by country music’s masters back in Nashville. Along our southern border, Mexican music filtered up and influenced an untold number of country music singers and songwriters, including one of the very best, Kris Kristofferson. And the West gave us cowboy songs and honky-tonk ballads that tumbled out of rowdy saloons, songs filled with longing and resentment—and having a good time.

A Mexican-American farm worker plays his guitar and sings in a California migrant labor camp, 1935.

Country music comes from the country, of course, but cities—Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Bakersfield, and especially Nashville—are central to its growth. Where you’re from, and what you still remember about home, and still wish for, is key in country music. Where you’re going, and how you’re planning to get there, figures prominently as well. Roy Clark, the owner (he lets us know) of two custom-made tuxedos, wasn’t afraid to brag about or wear on the TV show Hee Haw the bib overalls he wore as a boy in Meherrin, Virginia. Everyone (it seemed) heard songs in a particular place. And that place and those tunes became at times one and the same thing. When Hazel Smith first listens to George Jones singing “He Stopped Loving Her Today” on the car radio, she has to pull off I-64 near Nashville, she explains, and cry. Garth Brooks, from Oklahoma, has a similar experience, rooted in his place: “I was going to the store with my dad and I remember coming out of Turtle Creek, up there where I was going to take a left by the blue church, heading north to Snyder’s IGA, and my dad had his radio on…and this lady says, ‘Here’s a new kid from Texas and I think you’re going to like him.’ And it was George Strait…. And it was that day, I looked and said, ‘That’s what I want to be.’ ” Marty Stuart told us, “When I was growing up on Route 8, Kosciusko Road, in Philadelphia, Mississippi, the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio ran right behind our house…. And I used to dream about getting on that train and riding…. I didn’t want to go to New York. I didn’t want to go to Hollywood. I wanted to go to Nashville and play the kind of music that touched my heart.”

The biggest tension was the most obvious and the most difficult to reconcile: the tension between the words and the music. As filmmakers, we understand a bit about that dynamic as we seek to find the right balance between our words and the images that accompany them. Or vice versa. It’s a fundamental challenge, and each successful film has to find its own organic equilibrium. It is the same in country music, where the words and the music often add up to so much more than what the notes on the page indicate. That was where the art was made. That was when the whole became much greater than the sum of its parts. We looked for that moment everywhere, but it refused to yield to any formula of discovery and always defied description. Everything, every song that tumbled out, success or failure, was unpredictable in the extreme. Gradually, we began to see the film we were making as a complex overlay of all these tensions. From the first episode to the last, songs and their lyrics became akin to our human characters. Some were like Marty Stuart’s “ancient tones,” around as long as the hills have been, their truths, however, as fresh as today. Some were brand new, shockingly new, but they often sounded as if they were hundreds of years old. Some were like “heirlooms,” as Dolly Parton told us, songs passed on from generation to generation to generation. In our series, these songs appear and reappear, “old ghosts” (Marty would say again), as powerful in their rebirth and influence as, say, the music and memory of Hank Williams. In this way, we follow an old hymn that is rearranged by an African-American minister, only to be reworded by the Carter Family, finally ending up as Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land.” “Mule Skinner Blues,” one of Jimmie Rodgers’s greatest tunes, undergoes no less than three more “rebirths” in our film—with Bill Monroe, the Maddox Brothers and Rose, and Dolly Parton each reimagining it for a new generation. “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” about burying one’s mother, becomes one of the most joyous and most sung songs in all of American music, its sad lyrics left essentially unchanged.

Mother Maybelle Carter performs at the Opry, with Chet Atkins (left) on the guitar, 1955.

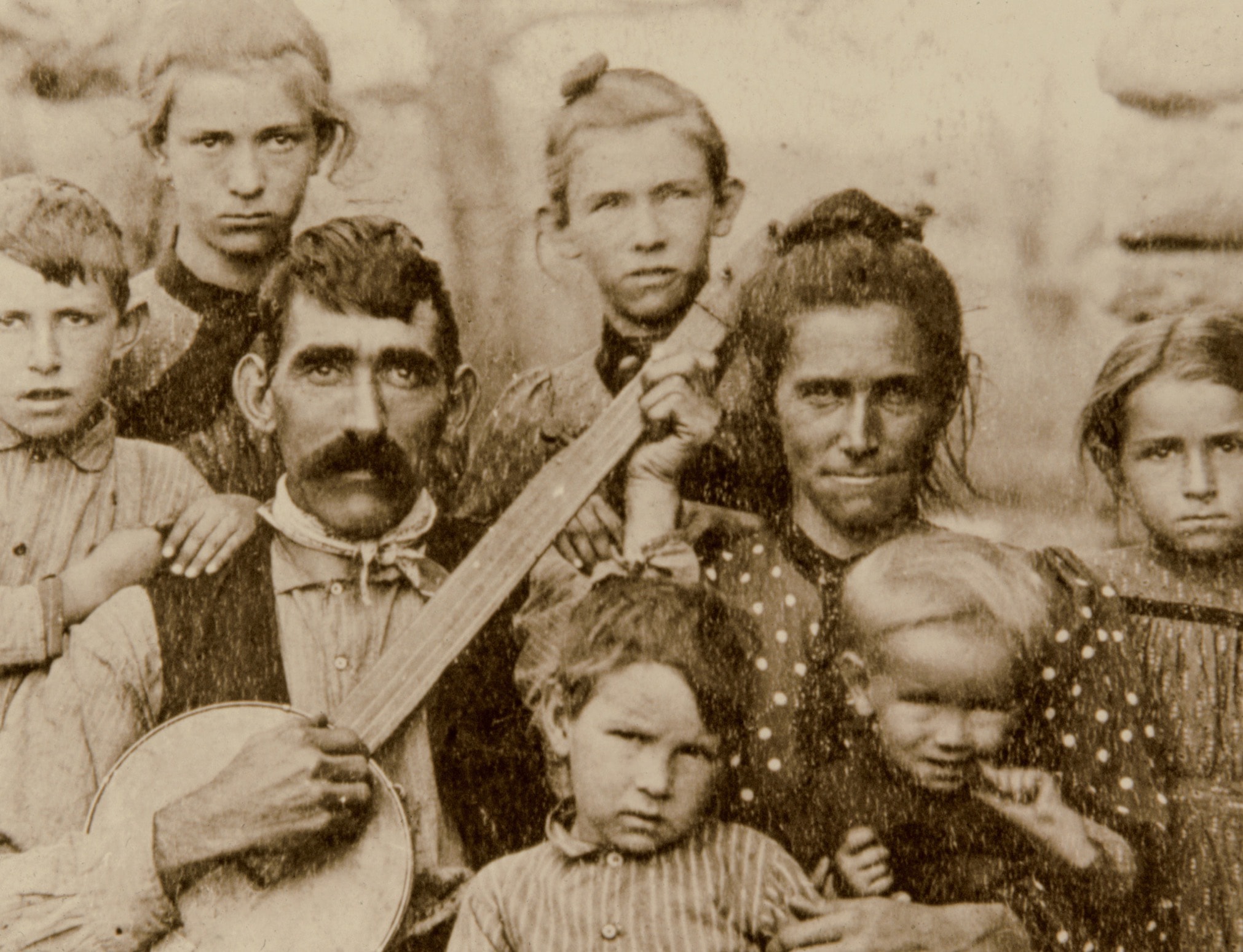

Along with this often exhilarating appreciation of the tension between the virtuous and the rascal, between black and white, and men and women, between regions, between the conformist and the contrarian, between the authority of tradition and the thrill of the experimental, country music is also hugely about rising up from the bottom, about striving, and the overweening ambition to better oneself and one’s family. A disproportionate number of country music’s greatest stars were born into a stultifying poverty reminiscent of the Great Depression. (For many of our characters it was the Depression.) Dolly Parton’s parents paid the doctor who delivered her with a sack of cornmeal. Roger Miller came from a town in Oklahoma so small and so poor “that we didn’t have a town drunk, so we had to take turns.” Rose Maddox from Boaz, Alabama, and her brothers and parents, had to live in a warren of unused drainage culverts, along with many other families and transients, all labeled “Okies” by their unforgivingly hostile California neighbors. Country music became their way up and out. So impressive is this manifest ambition and obvious drive—the need to escape the specific gravity of that poverty (or other childhood traumas)—that we all came to see this poverty as an essential ingredient of each artist’s greatness. Negotiating and reconciling grief and loss, privation and suffering, made them better equipped to pass on the essential truths country music has always been able to convey.

A young Hank Williams, who became the “Hillbilly Shakespeare,” c. 1940

The key for many of us was understanding what the musicians and singers and songwriters themselves understood country music to be. In interview after interview, they all came back to us with words like “simplicity” or “authenticity” or “truth.” Loretta Lynn told us, “If you write the truth…and you’re writing about your life, it’s going to be country. It’ll be country ’cause you’re writing what’s happening. And that’s all a good song is.” Speaking of Sara Carter’s remarkable voice, Rosanne Cash said, “[It’s] like wailing at the grave, that kind of keening…so plainspoken and so without any kind of embellishment or frill, just telling the truth, one note at a time.” For Hank Williams, it could be summed up in just one word: “sincerity.” Referring to Williams and his stunningly direct and exceedingly emotional lyrics, Rodney Crowell said, “When an artist gets it right for themselves, it’s right for everyone.” Emmylou Harris, the angel who more than once has “rescued” country music and reminded its listeners of its core values, echoed Hank Williams, saying, “The simplicity of country music is one of the most important things about it. It’s about story and the melody and the sound and the voice and the sincerity of it.”

Eventually, for many of us struggling to understand this deceptively simple music, all those old tensions would at times evaporate, the binary combat subsumed by larger, more important human themes only art (especially music, not exposition) seems capable of comprehending. And so our film gradually became, as well, about life and death, collaboration and reconciliation, loneliness and despair, falling in and out of love, missing someone, sinning, forgiveness and redemption. We found ourselves searching each other’s eyes for help as we listened and watched, finding that we were all unexpectedly in tears as the lights came back on in our editing room after a screening. At first, we didn’t quite understand the music’s great gift. Finally, we realized it was right in front of us, in the elemental directness of the songs nearly everyone we interviewed spoke about and the startling complexity of the artists we ended up highlighting in our series. In the end, it came down to recognition—of ourselves, of the other, of the immense power at the heart of those words and music. “At the end of the day,” Vince Gill, who wrote one of the most poignant hymns in all of country music, told us, “all I’ve ever wanted out of music was to be moved. I love the emotion of music…. There’s something that it does to my DNA that I can’t explain.” Neither can we. But it’s there. Help yourself.

KEN BURNS

Walpole, New Hampshire

The music of the Southern mountaineer is not only peculiar, but like himself, peculiarly American. Nearly all mountaineers are singers. Their untrained voices are of good timbre, the women’s being sweet and high and tremulous, and their sense of pitch and tone and rhythm remarkably true.

The mountain people do sing many ballads of old England and Scotland…. [S]ome have been recast, words, names of localities and obsolete or unfamiliar phrases having been changed to fit their comprehension.

The mountaineer is fond of turning the joke on himself. He makes fun of his own poverty…his hard luck and his crimes. Once touched by religious emotion, however…the deeps of his nature are reached at last.

There are simple dance tunes, with a rollicking accompaniment…peculiar fingerings of the strings, close harmonies, curious snaps and slides and twangs, and the accurate observations of an ear attuned to all the sounds of nature. The fiddler and the banjo player are well treated and beloved among them, like the minstrels of feudal days.

[T]hese tunes are bound with the life of the singer, knit with his earliest sense-impressions, and therefore dearer than any other music could ever be—impossible to forget as the sound of his mother’s voice.

Surely this is folk-song of the highest order. May it not one day give birth to a music that shall take a high place among the world’s schools of expression?

EMMA BELL MILES,

The Spirit of the Mountains (1905)