The Vietnam War was one of the most divisive conflicts in American history. After more than a decade of involvement in South Vietnam, Washington negotiated a peace with Hanoi in 1973. US combat operations officially ended on January 28, 1973, when a ceasefire took effect. The United States’ military disengagement in other Southeast Asian nations, however, would take longer. Washington officially stopped bombing in Laos on February 21, but continued authorizing sorties until April 17. On August 15, the last military combat sorties over Cambodian skies concluded the US war. Yet despite massive aid and some political support by Washington, Saigon still fell in 1975. Laos and Cambodia turned into communist states.

These actions seemed to confirm fears of a regional communist takeover, apparently proving the “domino theory” first advanced in the 1950s. One of the few Southeast Asian nations that seemed to escape revolution was Thailand, but its government was nevertheless changing. Although a shadow of its former self, the only sizeable American military presence in the region was in Thailand and the Philippines. Despite a calm exterior, elements within Bangkok wanted to expel the US Air Force (USAF) units stationed throughout the country.

During the Vietnam War, North Vietnam had largely moved from an insurgency to a conventional war to overthrow the Saigon government by 1975, and now had designs on other neighboring states. The Laotian and Cambodian governments, meanwhile, faced counter-revolutionary movements. Both governments had been, at times, willing to accept American aid in exchange for their support in fighting a secret war against the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC). With Washington pulling out of South Vietnam, however, the administrations started to crumble. The Laotian leadership, without massive American aid and bombing support, suffered continuing setbacks against communist Pathet Lao and NVA units bent on the government’s overthrow. Laos was valuable to the North Vietnamese as an indirect route to South Vietnam. A ceasefire on February 22, 1973, allowed the communists to control wide areas of the countryside, and although a coalition government was formed under Prince Souvanna Phouma, the Pathet Lao continued to consolidate its power. Eventually Laos fell to the communists in December 1975.

In Cambodia, Defense Minister General Lon Nol, sympathetic to American foreign and military aims, had clashed with head of state Prince Norodom Sihanouk over national policies, including the prince’s complaints about American and South Vietnamese border incursions, bombings, and aid. US and South Vietnamese forces had briefly invaded Cambodia in late April 1970 to oust Vietnamese troops and destroy supplies in the border area with South Vietnam. These differences strained relations between Washington and Phnom Penh, and in 1970 Lon Nol launched a coup, forcing Sihanouk to abdicate. His assumption of power sparked a war with the Khmer Rouge, Cambodian communists supported by the North Vietnamese and Chinese. He would eventually leave office, but later return to power in 1972, when he suspended the constitution. Lon Nol announced a ceasefire on January 29, 1973, but it never took hold. Khmer Rouge, NVA, and VC forces controlled rural Cambodia, and they had bottled up Lon Nol’s forces in the cities.

Phnom Penh relied heavily on American airpower and support to survive. Khmer Rouge forces, with support from Sihanouk, continued to fight on. They started to surround Phnom Penh, shutting down the Mekong River access and shelling and rocketing Pochentong Airport, the major airfield near Phnom Penh. Despite American air-delivered aid, it was not enough to stem the tide. Lon Nol abdicated and left for Hawaii, and the Khmer Rouge took over the country in April 1975.

The leader of the Khmer Rouge, Pol Pot, did not allow Sihanouk to return to power. Instead, he began a process aimed at rebuilding Cambodia into a self-reliant, agrarian state. He also carried out mass executions among the nation’s business owners, political opposition, government employees, Buddhist monks, and various ethnic groups, including Vietnamese and Chinese. Pol Pot also continued the border disputes with Vietnam and Thailand to demonstrate his resolve for maintaining Cambodian sovereignty. Cambodian military forces began to occupy disputed islands in the Gulf of Thailand. The Khmer Rouge also wanted to extend their territory to offshore waters. Foreign embassies and citizens were not immune to this onslaught. Pol Pot’s regime told foreigners to leave and, in some cases, forcibly removed them from Cambodia. These actions not only demonstrated Pol Pot’s xenophobic nature, but a vicious character.

American National Security Agency (NSA) signal intercepts became the most reliable information source available on Khmer Rouge activities. President Gerald Ford’s administration started receiving NSA signals intelligence, that indicated that the Khmer Rouge had initiated mass executions, re-education efforts, forced relocations, retribution actions, and family separations “on an unbelievable scale.” Within the White House, speculation ran rampant on why the new Cambodian government had taken these paths.

Future relations between Phnom Penh, Washington and other nations seemed bleak. Cambodia’s aggressive border behavior and willingness to execute its own people had the potential to cause more conflict within Southeast Asia. Fortunately, for Washington, the United States had largely withdrawn from the region. The only major American military presence in mainland Southeast Asia was in Thailand.

The Thai government had allowed American airpower to conduct bomber, fighter, reconnaissance, and tanker operations throughout the region virtually unconstrained. Bangkok stood by for years as F-105s and later B-52s and F-111s hammered Hanoi. This situation was changing, however. Communist revolutionary forces had tumbled Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, so Thailand could be next. Bangkok did not want to upset her neighbors unduly and bring a communist insurgency within Thailand. The United States had several air bases that maintained strategic bombers, tactical fighters, and special operations aircraft and helicopters. Although Washington did not have major ground forces in Thailand, its air and naval forces had the capability to conduct limited attacks on Vietnam, Laos, or Cambodia.

The United States had removed all of its combat units from the Republic of Vietnam well before 1975. Although Washington had supported Saigon with equipment and money, the US Congress had reduced aid to South Vietnam as the nation focused on other issues. Hanoi still looked south as it saw the American public’s interest in Southeast Asia rapidly waning. North Vietnamese and VC forces had already failed to conquer South Vietnam during the 1968 Tet Offensive, and Saigon turned back Hanoi’s conventional invasion in the 1972 Easter Offensive. By 1975, however, Saigon could not rely on massive American airpower or military resupply to stem another northern invasion. North Vietnamese divisions streamed south and pushed aside South Vietnamese units. Ford tried to get a $300 million aid package to Saigon, but the Congress refused to pass it. The Republic of Vietnam’s days were numbered.

Phouc Binh, a provincial capital, fell on January 6, 1975. North Vietnam took Ban Me Thuot, a key city in the central highlands, in March. South Vietnamese Army units fled to the coast. South Vietnam’s President Nguyen Van Thieu decided to abandon much of the highlands and concentrate on defending major cities, but Hue fell on March 26. Two days later, NVA forces took South Vietnam’s second largest city, Da Nang. Saigon was next.

Events escalated. On April 1, Cambodian President Lon Nol exited the country, and American forces executed Operation Eagle Pull to extract all American personnel from Phnom Penh on April 16. Some South Vietnamese forces started to switch sides; two South Vietnamese Air Force F-5Es dropped bombs on the Presidential Palace on April 8. South Vietnamese Army units deserted and threw away their uniforms as the North Vietnamese surrounded Saigon. Thieu resigned on April 21. A week later, the American embassy prepared landing zones for the coming helicopter evacuation.

South Vietnamese citizens had already started leaving the country by boat and plane well before April. The US government had helped 160,000 refugees flee the country. Many of these refugees fled by boat and entered camps throughout Asia. Tens of thousands of them eventually entered the United States. In early April, USAF C-5As had started Operation Baby Lift to transport infants, some of them orphans, out of the country. One C-5A crashed, killing 206 people, 172 of whom were children. Some alleged that a North Vietnamese SA-7 shot down the plane.

American Navy, Marine Corps, and USAF helicopters started the evacuation from the American embassy on April 28 under Operation Frequent Wind. USAF C-141 and C-130 aircraft also took people out of the country from Tan Son Nhut Air Base. Three South Vietnamese Air Force A-37s attacked the airfield and flew north. UH-1, CH-53, HH-53, and CH-46 helicopters, some participants of the Cambodian evacuation, pulled out 1,373 Americans, 6,422 foreign nationals, and the 989-strong marine security detachment. Two marines died and losses included three aircraft during the operation. On April 29, the end came. The last Americans destroyed equipment and documents at Tan Son Nhut and Ambassador Graham Martin left the embassy that day.

Thailand was also concerned about border incursions. Disputes about border locations, the ownership of islands, or land areas had plagued Southeast Asia for decades. Criminal activities took advantage of these disputes to operate drug smuggling or piracy operations. The VC and NVA had used the borders between Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia to operate the Ho Chi Minh trail, transporting supplies, arms, and troops into South Vietnam. By 1975, opposing sides moves across borders to support regional revolutionary and counter-revolutionary movements. Counter-revolutionary forces, for example, operated in southern and northeastern Thailand against the Khmer Rouge. Their activities spawned small cross-border attacks by Cambodia, supported by Vietnam and China. Another issue heightening tensions was the flood of refugees streaming across the Thai border.

In the second half of the 1970s, the United States was trying to forget about Vietnam and move on. Washington had started advising the South Vietnamese in 1961, but left after years of combat that resulted in 58,193 American deaths. By early 1975, observers witnessed South Vietnamese defenses crumble as the North Vietnamese pushed south. Without American military firepower and aid, Saigon was ready to fall. America had “lost” its first war, which ended with a massive helicopter and ship evacuation that put a stain on national honor.

The American public would not support any move to stem further communist expansion in Southeast Asia. To limit further American involvement in the region, the Congress started to restrain the power of the presidency. The Cooper-Church Amendment, passed in the Senate on June 19, 1973, restricted the nation from providing any funds to finance American military operations in Southeast Asia, unless authorized by Congress. This amendment undermined any perception that the United States would aid South Vietnam or other nation if it came under attack by a communist movement.

The Vietnam War had taken place in the context of a wider conflict, the Cold War. Since the end of World War II, the United States and the free world were in a state of continual conflict with the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact. The Nixon administration had tried to defuse tensions with its communist rivals, yet the United States still faced a huge arsenal of nuclear weapons aimed at it. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) faced the Soviet military on the German border. Armed proxies waged a war representing East and West, and Soviet-backed Arab states fought American-armed Israel. Marxist-led revolutionary movements sprouted throughout Latin America, Asia, and Africa. One of the hottest spots in the world was the border between North and South Korea, two countries technically still at war. Fortunately, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and America were trying to normalize relations after years of silence. Yet Washington was still unsure of its future path. American military forces around the world stood on alert to respond to any conflict, from an insurgency to global nuclear war. Demonstrating American military power was deemed as crucial to deter any future enemies.

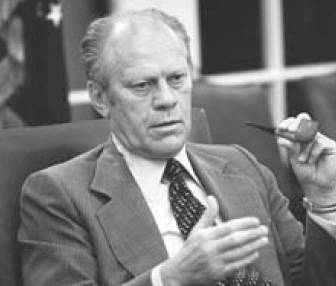

President Gerald Ford assumed the presidency after Richard Nixon’s resignation. The Mayaguez incident was his first foreign policy crisis. Ford was anxious to avoid a long negotiated settlement if Phnom Penh decided to hold the crew hostage. He wanted a swift resolution that included possible military action. (US Air Force)

The US government faced another challenge. Years of civil strife and protests over the Vietnam War had changed America’s outlook on the world. Within a few years, the optimism of the Kennedy administration’s internationalism disintegrated into insularity. Congress and the public were skeptical of any foreign adventure. Gerald Ford had inherited a country that was cynical about the government, especially after revelations about the Tonkin Gulf incident, the release of the Pentagon Papers, Watergate, and other issues. Given the mood of the nation, other powers wondered if Washington could act decisively.

The Gulf of Thailand did not seem to be an area of potential conflict to most Americans. After all, the reason for the war in Southeast Asia – saving the Republic of Vietnam – no longer existed. Trade ships plied the tranquil waters, but a new government, old rivalries, and plenty of weapons did not mix well. Under Lon Nol, the United States provided not only bombing sorties against the Khmer Rouge, but massive military and economic aid. After Cambodia’s fall, the communist insurgents now had access to American military supplies in the form of aircraft, small arms, and naval craft. Pol Pot had the ability to expand his power across Cambodia’s borders. The Khmer Rouge had the will and ability to launch a wide range of outrages. The Americans had left the region and it appeared they would not return for any reason; American military forces had returned to a training status throughout the Pacific.

Ship seizures, however, began to occur throughout the Gulf of Thailand, as Cambodian communists started to exert their new power in the region. The White House and other government agencies did not receive reports of any American ships attacked, however, so the government agencies did not issue immediate mariners’ warnings to the public or interested parties. Yet the attacks were growing in frequency, and included international commercial ships.

The seeming end of the Vietnam War in May 1975 was an illusion. A return to conflict in Southeast Asia began on a sunny afternoon south of the Cambodian mainland. Soon, world newspapers announced the capture and detainment of an American container ship. Inevitably, American military actions swiftly followed.