Ford, the NSC, CINCPAC staffers, and commanders in Thailand and at sea began to develop detailed operational concepts, which evolved into plans to send America into combat in Southeast Asia once again. Despite evolving conditions around the Sea of Thailand, the CINCPAC staff developed a plan to meet Ford’s objectives. Coordination between Washington, CINCPAC, Thailand, and forces afloat demanded precise timing. Retaking the Mayaguez, assaulting Koh Tang, searching for and rescuing the crew, and bombing targets on Kompong Som and Ream would require precision command and control.

Air Force Security Police, from Nakhon Phanom, volunteered to retake the Mayaguez. While trying to move forces to U-Tapao, a CH-53C transporting these volunteers crashed when the main rotor separated. All onboard died. The marines would have to board the ship and try to rescue the crew. (US Air Force)

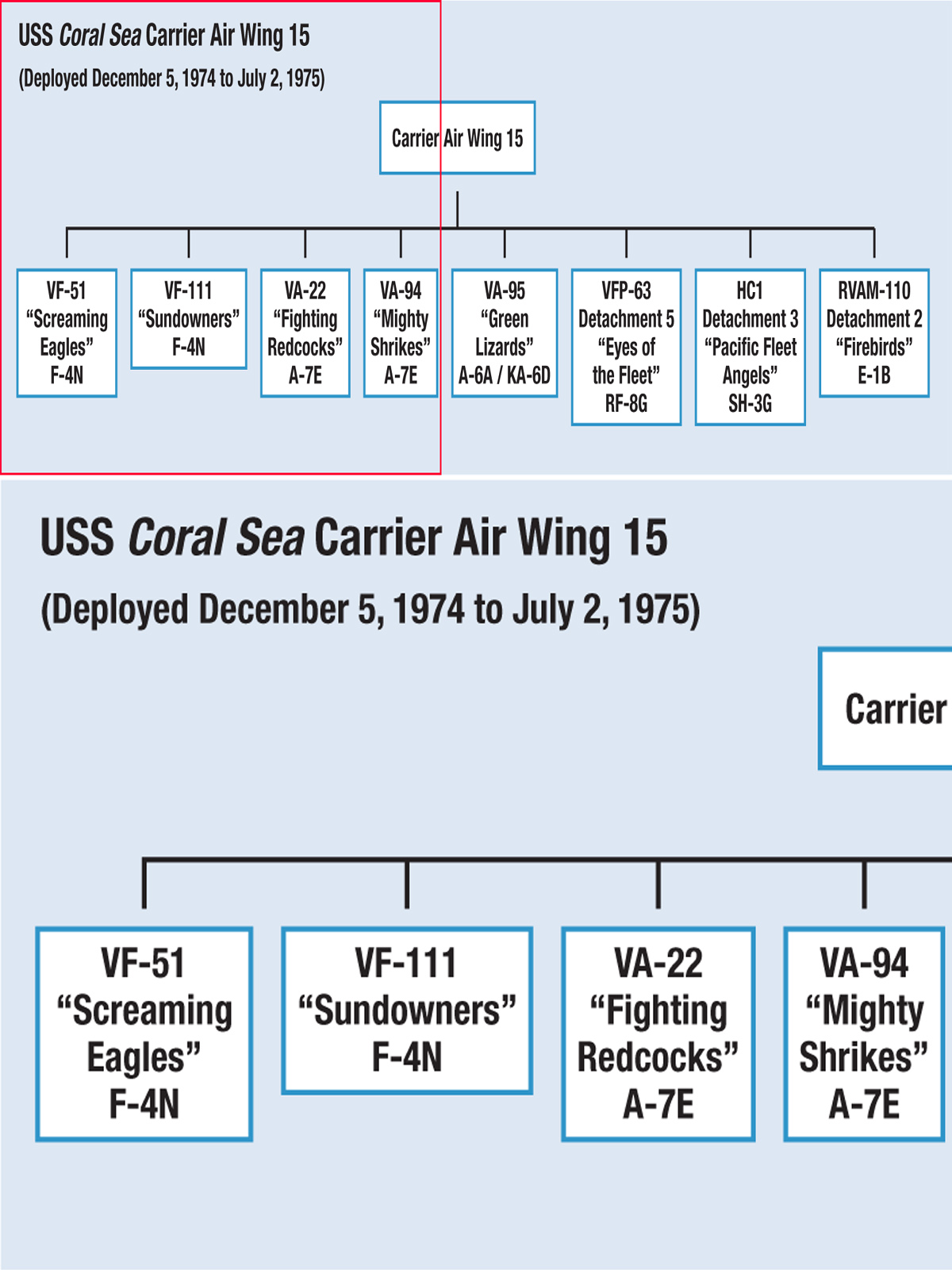

While the staffs exchanged ideas, external events shaped the final operational concept. The need to attempt a rescue without the Okinawa or the Hancock limited CINCPAC options – Thai-based USAF aircraft had to replace these Navy assets. Air Force rescue and special operations helicopters would instead move marines from U-Tapao to Koh Tang, where they would take the Mayaguez. Tactical aircraft from Thailand were designated to provide close air support and interdiction. JCS directives had already pushed CINCPAC to conduct reconnaissance missions, and USAF A-7D, F-4D/E, and F-111A aircraft had strafed and bombed Cambodian ships to isolate Koh Tang. Special operations AC-130A/Hs and F-111As watched Cambodian movements at night – Washington had already moved beyond considering Thai sensitivities.

The 7AF under Lieutenant General John Burns would control all Thai-based USAF units. Burns was also head of the United States Support Activities Group (USSAG). USAAG had inherited the role of the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV). Gayler designated Burns as the overall mission commander in charge of the assault on Koh Tang and boarding the Mayaguez. Burns had begun planning a rescue attempt even before Ford examined the options. USAF helicopters at Nakhon Phanom moved to U-Tapao to support the operation. Airmen from the 656th Security Police Squadron at Nakhon Phanom had volunteered to board the Mayaguez as an alternative plan. Tragically, on May 13 at 2130hrs, a CH-53C crashed 36 miles east of the base, killing all aboard including 18 of the volunteer Air Force security policemen for the mission and five helicopter crew members. The loss of life and a valuable helicopter would obviously affect the final plan, limiting the means to carry marines and reinforce them.

The distance from U-Tapao to Koh Tang is 190 nautical miles. A HH-53C or CH-53C would require about one hour and forty minutes to cross the distance. This meant a round trip of about four hours to resupply or reinforce any marine units on the island. Any further helicopter losses through combat or mechanical issues would severely disrupt operations.

The JCS-defined mission to CINCPAC was simply to retake the Mayaguez. Jones also directed CINCPAC to conduct military operations “to influence the outcome of US initiatives to secure the release of the ship’s crew.” Given this mission statement, CINCPAC had wide latitude to plan and change operations. The JCS provided Ford with an initial operational concept, but more detailed planning was needed.

Jones had notified CINCPAC to start all military operations on May 15 at sunrise. The marines were front and center in recapturing the Mayaguez and invading Koh Tang. The original plan to retake the ship envisioned using six USAF helicopters, but the Nakhon Phanom loss and some maintenance problems reduced the force to three. One option was to place the helicopters directly on the Mayaguez. The only area for a helicopter to land was on the containers, but unfortunately the helicopter’s weight on an aluminum cargo container might cause it to collapse. An alternative was to have the marines use ropes to deploy onto the freighter while the helicopters hovered. If Khmer Rouge forces were on the ship, however, then they could easily shoot at the helicopters and anyone leaving them.

This topside view of the Mayaguez shows the difficulty of trying to land helicopters directly on her. The aluminum containers could not support a helicopter’s weight. The bow and aft were too small. Having marines use ropes to land was too risky. Boarding by the Holt was the only viable option. (US Navy)

Helicopter deployment was rejected. Instead, the marine force from the Philippines, Company D of the 1/4 Marines, under Captain Walter J. Wood, would therefore arrive on and board the Mayaguez from the Holt. This plan involved using 48 marines, 12 Navy and Military Sealift Command (MSC) personnel, a USAF explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) team, and an Army Cambodian linguist. The Navy and MSC crew would operate the recaptured ship and help move it out of the area. Planners feared that the Khmer Rouge might have placed explosives on board the vessel, and they would detonate these if the Americans attempted to take it. The EOD team, therefore, would search the vessel and make it safe if need be. Photographs from reconnaissance aircraft helped identify 30 Cambodians on board. The Holt and her crew could support the marines if they were in a fight. Once the Mayaguez was under American control, the Holt would then escort it to safety.

The Khmer Rouge (meaning “Red Khmer,” the Khmer being a major ethnic group in Cambodia) started as a fringe communist group in rural areas in Cambodia. Their rise to power came about due to the actions of Cambodian generals under Lon Nol, who overthrew Prince Norodom Sihanouk. Sihanouk supported the Khmer Rouge in his quest to return to power. The Khmer Rouge, formed by Pol Pot, would eventually kill between one and two million people – no one truly knows how many Cambodians and foreigners lost their lives under the Khmer Rouge. Their goal was to return Cambodia, later renamed the Democratic Republic of Kampuchea, to the more simple life of an agrarian state. Pol Pot also wanted to eliminate all Western influences.

The Khmer Rouge, aided by the North Vietnamese and VC, started a communist insurgency against the Lon Nol government in 1970. This insurgency successfully controlled about one third of the country. For five years, Lon Nol, supported by Washington, battled the Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese. American secret bombings in 1973, the ceasefire with the United States, the growing number and success of Khmer Rouge insurgents, and the desire to capture South Vietnam caused Hanoi to move away from Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge took up the slack and they continued their war against Lon Nol. Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge eventually forced Lon Nol from power and Phnom Penh fell in April 1975. Many of the Khmer Rouge followers were teenagers and children. The implementation of Pol Pot’s deadly policies took on an even more sinister face when these young communists administered them.

Under the Khmer Rouge, any Cambodian government workers, business owners, educators, or those who disagreed with the regime were marked for arrest, torture, and death. The Khmer Rouge also wanted to kill any intellectuals. Suspicion fell on any Cambodian who spoke a foreign language, since that ability indicated an education. Religion was banned, especially Buddhism. No one could own personal property. Cambodians wearing glasses, using a watch, or possessing any other technology also met with instant death.

After taking control of the country, the communists eventually abandoned cities and closed any facilities that used modern technology. The country was reborn from “Year Zero.” Schools, monasteries, temples, and businesses closed. The Khmer Rouge rebuilt society by sending citizens to rural agricultural camps and farms. Mass evacuations moved the population to these ideologically run collective farms and a brutal life without money and material goods. Phnom Penh’s aim was to triple food production to become self-reliant. One of the only countries that maintained a very limited, distant relationship with Phnom Penh was China. In reality, the collective farms became death camps. Any sign of disobedience would end a worker’s life. Many died due to overwork, starvation, and disease. The reign of terror ended in 1979. Continued border skirmishes with the Vietnamese and crimes against humanity forced the Vietnamese to intervene. Pol Pot faced arrest and trial, but he only served house arrest, and died in April 1998.

The main effort of the operation was a marine assault on Koh Tang. Helicopter availability reduced the assault force to eight CH-53C and HH-53C aircraft. Along with the accident loss and maintenance problems, the USAF had to keep some helicopters in reserve for rescue and recovery operations. The first assault wave would set 175 marines on the island. Other waves would deliver additional marines, ultimately deploying a total force of 625 marines and 25 other personnel. The initial wave would secure opposite sides of the island and search an area that included a fishing village where the Khmer Rouge might hold the Mayaguez crew.

These operations required support from the USAF and the Navy. 7AF assets could provide day and night aircraft coverage over Koh Tang and the Mayaguez. Their main mission was to give close air support to the marine ground support force on the island. USAF aircraft would prevent movement by any small Cambodian watercraft in the Koh Tang and Poulo Wai area. Planners also assigned Thai-based HC-130P and at least two HH-53C aircraft for search-and-rescue operations. Naval vessels would provide offshore gunfire support.

SAC units in Thailand and Guam also had support missions. The approved JCS concept included four B-52D cells of three aircraft to attack Kompong Som harbor, Phumi Phsar Ream naval base, and Ream airfield. Later plans specified one cell each against Ream airfield and naval base. SAC planners readied the other six aircraft for Kompong Som. Twelve KC-135 tankers supported the attack force. The initial B-52 attack would occur three hours after the first assault on Koh Tang. SAC tankers from Thailand would also refuel any 7AF jets. The plan called for continuous coverage by at least one EC-130 to serve as an on-scene mission coordinator. The final operational concept also included authorization to use the BLU-82, a 15,000lb conventional bomb designed to clear a landing zone for helicopters from dense jungle terrain. Philippines-based C-130 aircraft would deploy the weapon from a parachute.

US Navy carrier aviation also played a major role in the operation. Like the 7AF aircraft, carrier A-6A and A-7E aircraft from the Coral Sea had authorization to restrict Cambodian shipping movements around the Koh Tang and Poulo Wai islands. Naval aviation, when in range, would also conduct daytime armed reconnaissance missions in the area. Ford might have the option to use Coral Sea aircraft strikes on Kompong Som and the Ream complexes. He had to choose between B-52D and Coral Sea aircraft to attack the Cambodian coast.

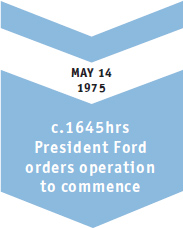

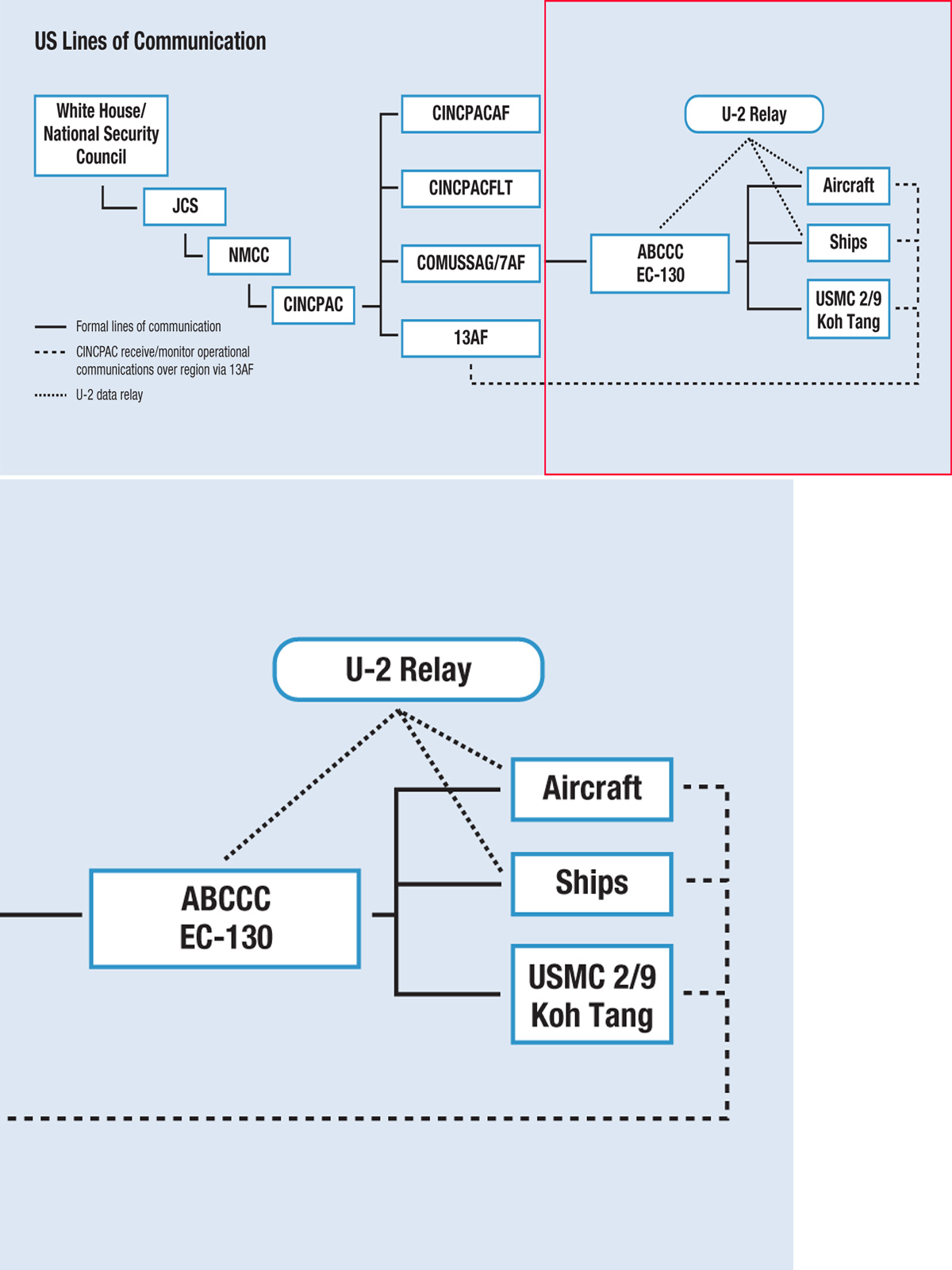

The final and crucial determination centered on the command and control structure. Ford gave CINCPAC overall control of the operation, and the JCS also designated Commander USSAG (COMUSSAG)/7AF as the on-scene coordinating authority for all supporting forces. CINCPAC staff on Hawaii had to control activities regarding CINCPAC, COMUSSAG/7AF, and the marine forces operating in Thailand and on Koh Tang. The only major command and control element outside of CINCPAC was the SAC B-52D force at Guam.

The mission concept was not without controversy. Local commanders using the concept to make detailed plans would need more information and required extensive coordination. Some of their concerns led to options that delayed decisions or forced commanders to adapt rapidly to changing requirements or events. Still, the priority of the mission rested on safely rescuing all of the crew.

Another priority included avoiding casualties, friendly and civilian. One of the lingering psychological remnants of the Vietnam War was the American public’s aversion to casualties. Ford and Kissinger, however, were also advocating the bombing of the Cambodian mainland, partly to restrict Khmer Rouge reinforcement or thwart any air or naval threat, despite overwhelming American air superiority and growing naval strength in the area. The final priority was American/Thai relations. Bangkok had allowed American military forces to maintain a foothold in Southeast Asia, despite Washington’s retreat from Cambodia and Vietnam. Maintaining good relations with any country, especially ones bordering communist states, would potentially be difficult after the Mayaguez rescue.

A-7Ds, like these, gave CINCPAC a variety of capabilities to strike the Khmer Rouge. The A-7Ds from the 388th TFW provided close air support and interdicted boats in the area. A month after the incident, the Thai government forced America to start pulling aircraft out of the country. (US Air Force)

When the F-111A first deployed to Southeast Asia, it was plagued by problems with its terrain-following radar, causing several aircraft to crash. By 1975, the Air Force fixed the problem and they served admirably. The F-111s would provide close air support and interdict boats. (US Air Force)

Washington had several operational objectives and priorities that came into direct conflict with one another. Accidental bombing of a ship or an inadvertent firefight on Koh Tang might kill members of the Mayaguez’s crew; bombing Kompong Som and Ream could achieve the same result. Similarly, Khmer Rouge defenders could exact revenge on the crew members or the ship once military operations began. A direct assault on Koh Tang and the ship might result in an unacceptable number of Americans killed or wounded – the CH-53C helicopter crash had already cost 23 Americans lives even before any rescue attempt. The initial wave of marines landing on Koh Tang faced an indeterminate number of Cambodian defenders. In addition, using B-52Ds to bomb an urban area could inflict heavy civilian casualties, harden Cambodian resistance, and turn world and domestic opinion against Washington. Keeping the Bangkok government placated was also at odds with the need to use USAF-based assets at U-Tapao and staging marines from Thailand to take the ship and lead the assault on the island.

Time and uncertainty weighed heavily on Washington. Dynamic events dictated changes to the priorities. For such a complex set of interrelated activities, there was no written operational plan provided to or discussed by the CINCPAC and other forces that would ultimately conduct the rescue of the Mayaguez and her crew. The JCS, CINCPAC, COMUSSAG/7AF, PACFLT, and the marines needed more than concept, they required a detailed plans and actions.

One can here see the narrow gap between the East and West Beaches. The distance from one beach to the other was about 1,200ft. The planned marine assault called for an initial hook-up between the two forces. This assumed few Cambodian defenders, a false assumption. (US Air Force)

Koh Tang is about 3.5 miles long and 2 miles wide. It sits approximately 27 nautical miles from the Cambodian coast. Jungle-covered terrain dominated the island, with a small rise in the center, designated Hill 440. Before the Khmer Rouge had taken control of Cambodia, the island had a small communications site and was home to limited fishing activity. The northern area also contained two relatively shallow beaches on the east and west coasts. The East Beach had a longer, coral sand beach that could serve as a main landing zone. The West Beach was much smaller, but if the marines could land simultaneously on both beaches, then they could drive towards the center, take the fishing village, and possibly rescue any Mayaguez crew members. The East Beach cove area had also been the location where the Khmer Rouge had removed the Mayaguez crew by fishing boat. The marines noticed that the East and West Beaches were the best approaches to take Koh Tang; so did the Khmer Rouge.

Men from 2/9 Marines in Okinawa began to get ready for deployment on the afternoon of May 13. At U-Tapao, Colonel John M. Johnson, the designated USMC ground force commander, had ordered Lieutenant Colonel Randall W. Austin, the 2nd Battalion commander, to get his force to Thailand. Ten C-141s moved Austin’s battalion and other elements from Kadena Air Base to U-Tapao throughout May 14. Six other C-141s also transported 118.3 short tons of equipment, supplies, and ammunition from Okinawa to Thailand to support the operation. Austin’s force totaled 1,095 personnel. The force was designated Battalion Landing Team (BLT) 2/9. BLT 2/9 included troops that had just completed field-training exercises in Okinawa. The marine force included E and G Companies, headquarters elements, a heavy weapons section to include 4.2in and 81mm mortars, and other support teams.

Austin’s mission was to take Koh Tang and hold it for at least 48 hours. His marines would then search the island for any captives. They would also ensure that Khmer Rouge forces did not interfere with the Mayaguez boarding action by firing upon the ship from the island – the attack on Koh Tang would occur simultaneously with the boarding of the Mayaguez. The 40th ARRS and 21st Special Operations Squadron (SOS) only had 11 operating helicopters. With three helicopters assigned to 1/4’s transport to the Holt, Austin therefore had only eight helicopters to conduct the first of three planned assault waves. The first wave would send Company G onto the East and West Beaches; the planned attack force included 163 marines, 11 Navy corpsmen, and three Army translators. Captain James H. Davis, the Company G commander, and a reinforced platoon would land with two helicopters on the West Beach. The rest of Company G would land on the east end with the rest of the helicopters. A second wave would bring in Company E. The third wave would end the assault, which in total would put about 625 marines and 25 other personnel on the island.

Completing a helicopter assault against an unknown enemy force, one that may have had time to entrench itself, was an uncertain challenge. To avoid accidently killing captive Mayaguez crew members and to achieve surprise, the first assault wave would dispense with any naval gunfire support or pre-invasion air attacks to soften up Cambodian defenses. Once on the island, a Marine forward air controller (FAC) could direct USAF close air support and any naval gunfire support from the Holt and the Wilson. Later, the Coral Sea attack squadrons could provide additional firepower. The onsite FAC would have good situational awareness and local information to direct accurate fire. In an attempt to enhance mission intelligence, Austin had conducted an afternoon aerial reconnaissance over Koh Tang on May 14. Using a handheld 35mm camera, he flew over the densely forested area at 6,000ft in an Army U-21 airplane. This minimum altitude was above effective enemy antiaircraft fire, but it was also too high to photograph any details on the island. The island had no discernable landmarks; the jungle foliage had created an effective defensive cover for the Khmer Rouge.

If the initial intelligence estimate of about 18–30 Khmer Rouge defenders on Koh Tang were true, then the marines’ attack would have no problem overwhelming them. There is some question about whether anyone provided the IPAC or DIA estimates to Johnson and Austin. A 307th SW intelligence officer had briefed the Air Force helicopter crews and allegedly, a marine officer was present. Unfortunately, the island landing planners did not have this vital piece of information about Cambodian ground strength, details that may have changed Austin’s plan. The marines did not envision landing on a defended beach area emplaced with heavy weapons. Reinforcements, if required, might take more than two hours to arrive due to the helicopter transit time.

HH-53Cs had a distinct advantage over the CH-53Cs; they were air-refuelable. This HC-130P allowed HH-53Cs to remain on station to conduct extraction or rescue operations. In addition, damaged helicopters could refuel and avoid crashing due to fuel problems. The Coral Sea’s appearance would help to alleviate this problem for the CH-53Cs by providing an offshore base. (US Air Force)

Khmer Rouge forces had actually built several defensive positions on Koh Tang; Cambodian military units had to defend the territory against potential Vietnamese incursions. On the island, the Khmer Rouge battalion commander, Em Son, nominally had 450 soldiers. The battalion was part of the Khmer Rouge’s 3rd Division, assigned to the Cambodian coastal areas. During the Mayaguez incident, however, he had no more than 100 defenders. Em Son’s men had a variety of weapons, which included captured American military stocks. The garrison had created a trench system along the East and West Beaches, dotted with three-man fighting positions and bunkers. The defensive lines also included overlapping fields of fire from entrenched machine-gun positions and mortars. Ammunition storage areas supported the trench defenses. The Khmer Rouge headquarters was near Hill 440 along with a radio site.

The planned execution time for the rescue mission, calculated by the JCS, was 0542hrs on May 15. This time was the four minutes before Koh Tang official sunrise. Unfortunately, the dawn breaks about 20–30 minutes before this time, so there was the danger that the Khmer Rouge defenders might be able to see the first wave’s helicopters arriving and take immediate action. The first wave of helicopters would leave U-Tapao at 0414hrs that day. Plans called for the last wave of the initial marine assault force to depart at 0423hrs. The marines would deploy in three helicopter flights. The first three HH-53Cs would go to the Holt and carry out the Mayaguez recapture team. Five HH-53C and CH-53Cs would land the initial marine force on Koh Tang. The simultaneous boarding of the Mayaguez would require additional time. Some of the USAF helicopter crews had experience landing their aircraft on the aircraft carrier Midway during Operation Frequent Wind, the evacuation from South Vietnam. The Midway’s landing deck, however, was much larger than the small helicopter pad on the Holt. Transferring Company D might be difficult, especially in the early daylight. The Holt also had to close on the Mayaguez and allow Wood’s men to gain access to the ship.

Once BLT 2/9’s mission was complete, the JCS would extract the marines. The NSC was still apprehensive about alienating Bangkok by using U-Tapao as a base of military operations against Cambodia. There was no hiding from Bangkok the use of 7AF and SAC resources from Thailand in the operation, since Thai forces also used the airfields. The Thai government had already asked questions about Company D’s arrival at U-Tapao. Austin’s battalion created more angst among the Thais. JCS planners advanced two options: marine recovery on the Coral Sea or return to Thailand. Sending the marines to the Coral Sea would avoid angering the Thais again. As the aircraft carrier moved closer to Koh Tang, the extraction might not require as much time as the return to Thailand and the carrier could provide more support. In addition, Navy maintenance crews could help repair and refuel any helicopters. Medical support was also available to any wounded personnel. The return to Thailand therefore became a last resort.

The other major elements of the operation were to be a series of attacks on several locations on the Cambodian coast, including Kompong Som and the Ream area complexes. CIA analysts had discounted Kompong Som as an active port. Its main activity was a resupply point for the VC and Khmer Rouge naval ships. The original reason to attack the harbor and airfields was to restrict any possible Cambodian reinforcement or interference with American military actions around Koh Tang. American bombing could also convince Phnom Penh to release the crew, or else the Cambodian capital might be the next target. A more strategic reason was a demonstration of American resolve – bombing Cambodia was a message to Phnom Penh and others that Washington had the political will and military means to retaliate globally. Kissinger and other NSC members had discussed the impact of the Mayaguez incident in relation to North Korea. With America’s seeming defeat in Southeast Asia, Washington wanted to demonstrate to Pyongyang not to confuse the Vietnam withdrawal with an unwillingness to defend South Korea.

The attack on the Ream airfield was of questionable value. The only Cambodian aircraft that might attack were T-28s, AC-47s, and some possible helicopter gunships. These aircraft had limited armament, serviceability, and operational capability, and the 7AF and Coral Sea F-4 combat air patrols over the Gulf of Thailand would make short work of them. Furthermore, both the Holt and Wilson had surface-to-air missiles that covered the area around Koh Tang and the Mayaguez. Jones and DCI Colby both argued that the Cambodian aircraft at Ream did not seem to be a major threat and opposed an attack on the airfield. White House Chief of Staff Donald Rumsfeld, however, pressed the point that if the Cambodians had the capability to launch military aircraft from the airport, then Washington had a “stronger argument” to bomb it. The Ream airfield remained a target.

The only unanswered question was the use of B-52s or the Coral Sea aircraft. The long distance from Guam, potential collateral damage and conflict escalation, and the prospect of congressional opposition convinced Ford to drop the B-52 option. B-52s carried more bombs than naval aircraft, but their value was in hitting area targets. A B-52 cell of three planes typically carried about 108 500lb bombs apiece. Jones had mentioned at an NSC meeting that the only targets of value seemed to be at the harbor of Kompong Som. RF-4C photo-reconnaissance jets had overflown the area, and spotted two freighters in port. Although the B-52 might not target the ships, there was a chance of them being hit by errant bombs. This unintended damage might affect the public perception of America’s military action, especially if the ships were vessels for neutral countries. Ford still wanted to use the B-52s, but settled on the naval carrier aircraft to conduct the mission. CINCSAC keep the Guam-based B-52s on a one-hour alert.

The Coral Sea had a stock of precision guided munitions (PGMs), such as the AGM-62 Walleye television-guided bomb and Paveway laser-guided bombs. PGMs offered Ford the ability to destroy specific buildings, warehouses, and other storage facilities. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral James L. Holloway had reported to Ford that the Coral Sea had 81 PGMs onboard, plenty to sustain several missions. The Navy pilots would reduce any collateral damage in the mission by deploying these weapons. Using carrier aircraft also allowed CINCPAC to cycle the Coral Sea A-6A and A-7Es to step up bombing missions.

Jones’ plan would send Coral Sea aircraft into the Kompong Som area and Ream around the time of the Mayaguez boarding. The NSC directed the JCS to have the Coral Sea aircraft’s time on target as 0745hrs for the first mission. Jones designated the first mission as “armed reconnaissance” and subsequent missions to include strikes against multiple targets. The targets included enemy aircraft at the Ream airfield, port areas, railway facilities, warehouses, and other buildings. Since no one could positively identify the two ships at Kompong Som harbor, they were left alone. Subsequent witnesses identified the ships as Chinese.

A RF-4C photographed the area where the Khmer Rouge might hold the Mayaguez’s crew, in an abandoned fishing village. This would be the marines’ center of attention for the helicopter assault. The Khmer Rouge did not hold any captives on Koh Tang. Notice the RF-4C shadow in the right bottom. (US Air Force)

At a May 14 NSC meeting, the CIA estimated that approximately 2,000 Khmer Rouge forces defended the Kompong Som area with a potential for adding another 14,000 soldiers from southwest Cambodia. Air defenses around Kompong Som and Ream were minimal. The Cambodians possessed 23mm and 37mm antiaircraft guns, and CIA analysts identified a single 37mm gun south of Kompong Som and two 37mm gun sites at Ream airfield. The effective range for these weapons was 3 nautical miles, capable of hitting targets under 14,000ft. Navy aircrew would not face any surface-to-air missiles. A-6A and A-7E crews could launch PGMs at enough distance from the targets to avoid any antiaircraft artillery rounds. The Khmer Rouge also had no interceptors capable of shooting down jets, so the air threat seemed negligible. Cambodian naval forces in port at Kompong Som and Ream, on the eve of the attack, were limited to 13 coastal patrol boats, ten riverine patrol boats, and one submarine chaser. These vessels did not appear to offer much opposition to any American attack. However, the Khmer Rouge could call on several landing craft, which could move about 2,400 soldiers and reach Koh Tang in four hours.

Discussion among NSC members on May 14 had included using the Coral Sea aircraft to attack Phnom Penh. The President quickly dismissed this option, since he wanted to focus on protecting the operation from any Cambodian reinforcements deploying from Kompong Som. In addition, if the Navy pilots struck only military targets, then there was little chance of killing any Mayaguez crew members, based on the strong assumption that they were not held in military facilities. Kissinger had, before the May 14 NSC meeting, a conversation with Ford in which he pressed the President to conduct the air strikes on Kompong Som. Ultimately, Ford would agree with Kissinger. At an 1145hrs meeting in the Oval Office, Kissinger thought the JCS would not pursue the attacks. He thought they suffered from the “McNamara syndrome,” and that they would “not be so ferocious.” Dr Kissinger also called Gayler “disastrous,” showing little confidence in the CINCPAC leadership to conduct the operation – the secretary wanted action.

By 1975, technical advances in communications had allowed Washington to talk to a regional commander or individual platoon commander in the field. The Mayaguez incident had national security implications that caught Ford’s attention. The operation’s command and control systems were complicated, as the operation was one of the first in which the highest levels of government could oversee tactical decisions. The implications were enormous. Senior officers could direct or countermand orders from subordinate commanders to their units. Demands for information might swamp communications systems. Similarly, decision-makers had access to both unfiltered and properly analyzed information.

The command and control system relied on a number of secure voice, teletype, and satellite communications systems. The White House had governance over all forces through the NMCC – the Pentagon control center issued orders from the President to CINCPAC. Coincidentally, Gayler was in Washington throughout the Mayaguez incident. The NMCC communicated through a JCS voice alert network, secure voice, and a secure teletypewriter message system. CINCPAC disseminated directives to Commander-in-Chief, PACFLT (CINCPACFLT) and 7AF’s immediate headquarters, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Air Forces (CINCPACAF). Although not in the direct operational chain of command, CINCPACAF had control of several support activities in the Philippines and he was still 7AF’s commander. CINCPAC had its own secure voice and teletypewriter capabilities. Gayler’s staff in Honolulu had a teletypewriter system to transmit written directives, but they also had access to a Defense Satellite Communications System capability to get instant contact with Burns.

The HH-53C played a major role during the assault and extraction of marines on Koh Tang. The aircraft were from the 40th ARRS from Nakhon Phanom. Its three 7.62mm miniguns provided suppressing fire that frequently stopped the Cambodians from shooting down the helicopters around Koh Tang. (US Air Force)

COMUSSAG/7AF could direct all naval, air, and ground operations from his Nakhon Phanom headquarters. During the operation, Burns turned on-site command over to an EC-130 Airborne Battlefield, Communications, Command, and Control (ABCCC) aircraft circling in the vicinity. The EC-130 ABCCC was codenamed “Cricket,” and its capabilities were critical to harmonizing the many simultaneous actions planned for May 15. A Cricket aircraft transmitted orders to all forces in theater, and its battle staff coordinated aircraft flights, deployments of forces, integrated requests for support, and other activities. Cricket talked to the marines through very high frequency (VHF), frequency modulation, and ultra high frequency (UHF) radio communications, while the EC-130 battle staff directed aircraft and ships mainly through a UHF radio link. A secondary system to support the ABCCC was a SAC U-2 aircraft, which served as a manual UHF relay and allowed Burns to communicate with any aircraft or ships in the area. COMUSSAG/7AF also could send and receive messages to CINCPACFLT ships via a high frequency secure teletypewriter. Unfortunately, staff ranging from CINCPAC to the White House could also listen to traffic and respond directly to any messages from deployed units in action.

Fears that B-52D bombing might produce heavy civilian and collateral damage forced Washington to reconsider their use in Cambodia. Instead, Coral Sea tactical aircraft armed with precision guided munitions, like this Walleye bomb, had to make the attacks. These weapons gave CINCPAC more capability to hit specific targets. (US Navy)

A-6As, from the Coral Sea’s CAW-15, participated in the attacks on the Cambodian coast. The A-6s pictured here are similar to the ones that hit Kompong Som and Ream. The aircraft had two crew members and could deliver ordnance with precision at night or under poor weather conditions. (US Navy)