YANG-CH’I/YANGQI (“Nourish Breath” or “Vital Energy”). This is the first (in alphabetical order) of five types of “nourishing” discussed in the texts of the Taoist religion. To “nourish” means to “feed, support,” or to “increase.” Vital energy is given to all living beings at birth, but its supply will run out, and that is the end of life. Taoists believe they can prevent exhaustion by various exercises, physiological and spiritual. (See also Breathing Exercises; Three Vitalities.)

YANG CHU/YANG ZHU: THE PERSON. A hedonistic philosopher who was probably a contemporary of Mencius (371–289 BCE?) and was fiercely attacked by him because of his selfish desires. He is sometimes portrayed as a Taoist or a proto-Taoist, but this is not a correct interpretation. It is true that there is a “Yang Chu Chapter” in the Taoist book Lieh-tzu, but this material juxtaposition is not a solid reason to call Yang Chu a Taoist. His ideas are far from Taoist, and have only a superficial similarity with the Taoist worldview. It is like Taoism gone crazy.

However, what Yang Chu has to say stimulates reflection. His outlook on life and death makes some sense if applied in moderation. Life is short, death is unavoidable; why not make the best of it and enjoy life to the fullest? Many religious preachers would attack this view violently, but still practice it secretly! If Yang Chu was a crook, he was not a hypocrite.

YANG CHU/YANG ZHU: THEMES. In the book Lieh-tzu, there is one chapter (Chapter 7), titled “Yang Chu,” which does not belong there. Superficially, there is some similarity with Taoism, such as spontaneity or naturalness, acceptance of death as an unavoidable fact, and “caring for life.” Yet, here these very Taoist principles are applied to an extreme degree (Taoism “gone crazy”!).

Spontaneity for Yang Chu means to follow all one’s sense cravings without restrictions; acceptance of death is seen as a permit for wild passionate living, since death is the end with only “rotten bones” left; and caring for life means to indulge completely and absolutely. Taoism, on the contrary, advocates restraint and moderation. Life may and must be enjoyed, but the life energy should be spent sparingly.

Two themes of the Yang Chu chapter are of particular interest. The first one because it was the ground for Confucian attacks against Yang Chu’s hedonism (in the Mencius); the second one for its extreme view of life and death and its resulting action.

Mencius accused Yang-chu of extreme selfishness: If he could save the world by sacrificing only one hair, he would refuse to do it. However, it is not certain that this is a correct appraisal of Yang’s position. It might rather be that if he could gain the world (become the world’s ruler) at the expense of just one hair, he would not do it. In other words, becoming a king does not interest him. Why look for trouble and heart disease, if life is so short?

That leads to the second Yang Chu motif, expressed in very realistic language: life is short, 100 years at the most (but not one in a 1,000 lives that long). Suppose one lives 100 years:

Infancy and senility take nearly half (40%?)

Sleep, wasted time, take 30%

Pain, sickness, sorrow, loss, anxiety 15%

Of the rest (15%—perhaps only 12%): times of contentment, without care, “it does not amount to the space of an hour.”

(Chapter 7, Graham: 139)

Maybe there is poetic exaggeration here, but to be realistic and honest, most of our lives are indeed spent in anxiety and psychosomatic discomfort. Why not try to enjoy the rest of it in pleasure?

. . . where is [man] to find happiness? Only in fine clothes and good food, music and beautiful women. (Graham: 139)

This desire becomes more urgent if we consider the end of life: In death, all people are the same. Cleverness, wealth, reputation, etc., do not affect the dead any longer. What remains is

. . . stench and rot, decay and extinction . . . saints and sages die, the wicked and the foolish die . . . in death, they are rotten bones. Make haste to enjoy your life while you have it; why care what happens when you are dead? (Graham: 140–141)

YANG HSI/YANG XI (330–386 CE). In the service of the southern Hsü family, he received divine revelations during the years 364–370. During a series of midnight visits, about a dozen “perfected beings” (chen-jen) came down from the heaven of Great Purity to transmit to him their instructions and scriptures (Strickmann, 1981: 82). These revelations became the nucleus of a body of texts, later called “Great Purity Scriptures.” They were the basis of the new Taoist school, Great Purity Taoism, also called Mao Shan Taoism, because the school settled on Mount Mao.

One of the principal “spirits” to descend was Lady Wei Hua-ts’un (who had died in 334 CE), a libationer (chi-chiu) in the Heavenly Masters School. Other “perfected beings” were Han immortals, local saints, and the three Mao brothers.

Yang Hsi’s revelations were written in an elegant style and praised by T’ao Hung-ching for their high literary quality. There has been some speculation about the method in which these divine revelations were received: Was it through “automatic writing” or through divinely inspired illumination? Opinions are divided. Yang’s elegant style seems to exclude the possibility of automatic writing. It was rather like revelations received in other religious traditions: St. John’s Book of Revelation, the Koran, and the visions of Swedenborg (Robinet, 1991: 120).

Yang Hsi became the second patriarch of Shang-ch’ing Taoism (after Lady Wei, who was considered to be the foundress).

YANG-HSING/YANGXING (“Nourish Nature”). Refers to the cultivation of one’s nature, and includes ching, ch’i and shen (the Three Vitalities). Or it can be understood in the sense of one’s spiritual nature only, one’s mind (hsin), in the Buddhist sense, as opposed to life (ming). Among the Northern and Southern Schools of Complete Realization Taoism, there was controversy as to the priority of the two, but it was agreed that both need to be cultivated (see also Nature and Life).

YANG-HSING/YANGXING (“Nourish the Physical Body”). This character hsing is different from the previous one; here it means one’s physical makeup, one’s body and its health. Most Taoists agree that the body must be “nourished,” not only by eating healthy food, but also by exercises (gymnastics, etc.), so that it becomes an effective instrument for mind cultivation. A minority would recommend physical hardships (fasting to the extreme), but one may wonder about the results of such endeavors.

YANG-SHEN/YANGSHEN (“Nourish the Spirit”). At birth, each person is endowed with original spirit (yuan-shen), which is dissipated in life by thinking, worries, etc. Through inner cultivation, this process can be reversed to the point where all one’s vitalities are transformed into spirit. Then longevity, even immortality, follows, as a Han dynasty text, Wen-tzu, says:

It is most important to nourish the spirit, it is of secondary importance to nourish the body. The spirit should be pure and tranquil, the bones should be stable. This is the foundation of long life. (Quoted by Y. Sakade in L. Kohn, 1989: 6)

YANG-SHENG/YANGSHENG (“Nourish Life”). This practice is almost identical with yang-hsing (“nourish the physical body”). To promote one’s physical health was the basis for all spiritual practices. “Life” can be nourished by physical exercises (diet, gymnastics, breathing, etc.), but also by meditation, as, for example, visualizing the inner organs and encouraging the protection of the indwelling deities.

YELLOW COURT SCRIPTURE (Huang-t’ing ching/Huangtingjing). One of the oldest Taoist texts, existing before the Shang-ch’ing revelations, but eventually incorporated into them. It had a great influence on later Shang-ch’ing texts, dealing with meditation.

This scripture does not provide technical methods of meditation, but it must be recited while the adept visualizes the inner gods dwelling in the body.

Apparently, the text as it is today consists of two versions, one called esoteric (nei-ching), which is most likely the earlier version. It is addressed to initiates, since it gives the names and appearances of the deities to be visualized. The other version, called exoteric (watching), is meant for noninitiates; it does not list the names of deities. Which one was the earliest version is still not clear: Textual comparison does not lead to any definite conclusion.

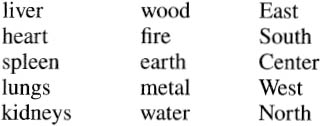

Although the text is difficult to understand, two important themes are clearly discernible: visualization of the viscera, and circulation of ch’i. By interior vision, one “must learn to see the form and function of the entrails and inner bodily organs, as well as the spirits that inhabit the body” (Robinet, 1979/1993: 60). As correlations of the Five Agents, the Five Viscera connect the microcosm of the body with the macrocosm:

It is extremely important for one’s physical as well as spirtual well-being to keep the viscera in good health, for if the viscera are injured, the indwelling spirits will leave. Moreover, only if the adept enjoys good health can he make progress in his search for the Tao. In order to be able to visualize the inner organs and their indwelling spirits, the organs must be made luminous, transparent. There are various methods to achieve this: magical herbs, absorption of the outflow of stars, the use of magic mirrors. Luminosity is a sign of good health.

Among the most effective means to maintain and increase good health is the circulation of ch’i, or circulation of ch’i and ching, translated by Robinet as “breath” and “essence” (Robinet: 83). The ch’i are the airy elements of the body, the ching (and saliva) are the watery elements. They operate like yang and yin. Through their union, a spiritual embryo may be born, leading to the creation of spirit (shen) and immortality.

(For an excellent analysis of the Yellow Court Scripture, see I. Robinet, 1979/1993: 55–96.)

YELLOW EMPEROR (Huang-ti/Huangdi). Name of a mythical ruler of antiquity, as well as of an important Taoist deity. His name literally means “Yellow” (huang) and “emperor, monarch, thearch, god.” The traditions about this deity are complex, the roles ascribed to him vary, but his popularity since Chou times until today remains strong.

As a celestial deity, he was one of the Five Emperors, ruling the four directions of space and the center, all worshipped by the feudal lords of the Chou kingdom.

A strong belief prevailed that Huang-ti’s reign was the actual realization of a golden age of peace and equality (T’ai-p’ing). This belief in him as the ideal ruler would later become an important aspect of Huang-Lao Taoism. On what perceptions this belief was built is not easy to say. It could be that at first the royal family of the state of Ch’i considered him to be their clan ancestor (this is based on an inscription dating from the mid-fourth century BCE) (Jan, 1981: 118). In the second century BCE, “the majority of feudal clans claimed Huang-ti as their ancestor” (A. Seidel, 1987, ER 6, 484–5). Even today, he is considered to be the common ancestor of all Chinese.

His claim to fame is not only based on being an ancestor, however. He is also a cultural hero, to whom various discoveries have been credited: invention of the calendar, first planting of crops, construction of houses and weaving of clothes, arranging of funerals, building of ships and carts, making of musical instruments, introducing of medicine. He is also credited with learning and applying the arts of the bedchamber, and thus contributing to the formation of immortality techniques. The list of credits vary, but they are all impressive.

Finally, his name has been connected with the first Taoist politico-religious movement: Huang-Lao Taoism. “Huang” stands for Huang-ti; “Lao” for Lao-tzu. Together, they symbolize perfect rulership: the sage king and the sage advisor.

In the Chuang-tzu, the Yellow Emperor is often cited—all together in 14 episodes. Sometimes he is presented as a sage; even the outlaw Robber Chih admits that “There is no one more highly esteemed by the world than the Yellow Emperor” (Chapter 29, Watson: 328). Yet, at the same time, he is criticized for bringing decline to a perfectly peaceful society, for plunging the world into the worst confusion.

In other passages, the Yellow Emperor appears to be a sage who, after receiving the Tao, “ascended to the cloudy heavens” (Chapter 6, Watson: 82). These different evaluations are obviously related to the particular stream of Taoism each author belonged to. In the Lieh-tzu, Chapter 2, titled “The Yellow Emperor,” there is an anecdote about the Yellow Emperor’s political career. At first self-indulgent, he started to govern for the benefit of the people. Then he “retired to live undisturbed in a hut . . . where he fasted to discipline mind and body and for three months had nothing to do with affairs of state” (Graham, 1960: 34). Once in a dream, he visited the country of Hua-hsü (utopia land). From then he started to rule his country with wu-wei. “After . . . twenty-eight years, when the Empire was almost as well-governed as the country of Hua-hsü, the Emperor rose into the sky [became an immortal]. The people did not stop wailing for him for more than 200 years” (Graham: 35).

Today, the Yellow Emperor, under a different but also ancient name, Hsuan-yuan, has become the focal deity of a new religion, Hsuan-yuan chiao (“Yellow Emperor Religion”), founded in Taiwan in the mid-20th century. This new religion has its own temples and has designed its own rituals and ritual garments (yellow in color). It “. . . teaches a mixture of Taoist, Confucian, and Moist [Mohist] ideas and labors for a renaissance of Chinese culture and for the reunification of the empire” (Seidel: 485).

YELLOW TURBAN REBELLION. A Taoist uprising against the Han dynasty in 184 CE. The middle of the second century CE was a period of political instability and palace intrigues, aggravated by natural disasters, bringing the country to the verge of collapse. A messianic movement arose in Eastern China, based on the vision of the Great Peace Scripture (T’ai-p’ing ching). Three brothers, named Chang, (see Chang Brothers), established a theocratic state that spread fast throughout eight eastern provinces. (See Introduction: Healing Cult in Eastern China.) The Changs assumed titles of the Lords General of Heaven, Earth, and Men:

. . . under their orders, they had a whole hierarchy of leadership whose functions were simultaneously military, administrative, and religious. (J. Gernet, 1982: 155)

The year 184 was the first of a new 60-year cycle: a good omen for a revolutionary new beginning and the establishing of a Kingdom of Great Peace and Equality. In that year, the T’ai-p’ing Tao movement had 360,000 men under arms. They wore yellow strips of cloth around their heads, hence the name of Yellow Turbans given to the revolt. The color “yellow” was chosen with intent: “green” was the color of the Han dynasty, which was doomed to destruction. “Yellow Heaven” would be established in the year 184.

Once determined to attack the weakened Han dynasty, the rebel armies planned to start in the city of Yeh (Hopei province). They had support from the eunuchs and palace guards in the capital city of Loyang. However, about ten days before the target date, the plot was betrayed by an inside informer, and the government took action. Many rebels were captured and executed. The date of rebellion was advanced, but to no avail. The leader Chang Chueh died of illness, and his two younger brothers were captured and executed in 184. Because of the strong military action taken by generals such as Ts’ao Ts’ao, the rebellion was suppressed, although some groups remained active for the next 20 years. Ts’ao Ts’ao, now rising to power, incorporated most of the rebel armies into his own elite troops, which helped him to unite the north. Although the Yellow Turbans did not succeed in overthrowing the Han dynasty, they weakened its power so badly that it never recovered. The dynasty finally came to an end in 220 CE, to be followed by the Three Kingdoms, with Ts’ao Ts’ao in the North founding the Wei Dynasty.

YI CHING/YIJING (Book of Changes). It is one of the five ancient classics of the Chinese tradition, inaccurately called “Confucian” classics (since they are pan-Chinese). The Yi ching is one of these oldest classical texts. Its beginnings go back to early Chou times, but its completion is much later: Warring States or Han period.

At first it was a technique of divination, used by the early Chou people together with the older Shang method of using animal bones (scapulomancy, osteomancy). This new Chou method, called Chou Yi (“Changes of the Chou”), was initially very simple. Milfoil or yarrow sticks were placed in a container; a bundle were removed at random, the remainder was counted. An odd number meant “lucky”: the action contemplated would be successful. An even number meant “unlucky”: action to be avoided. As time went on, results of each consultation were marked by symbols: a whole line ——— symbolized “lucky” (odd number, “one,” etc.); a broken line — — meant “unlucky” (even number, expressed by “two,” etc.).

The next step was to record the results of three consultations: One wanted to make sure the correct answer was given, so consultations could be repeated. The resulting symbols of three lines can be only eight in number, as follows:

The trigrams or pa-kua (symbols made of three lines), originally the records of a triple divination, were gradually interpreted in philosophical terms. They were seen as symbols of cosmic reality and human reality: (1) and (8) referred to heaven and earth; the intermediate ones were interpreted as symbols for thunder (2), water (3), mountain (4), lake (5), fire (6), and wind or wood (7). This stresses the cosmic aspect of the pa-kua. Human reality was superimposed on them: The original pair also mean father (1) and mother (8), the intermediate ones are three sons (2–4) and three daughters (5–7). Human characteristics were further added: father (1) stands for the creative, strong; mother (8) is the receptive, yielding; the six children are also opposing but matching pairs:

• first son (2), thunder, is the arousing inciting movement; first daughter (7) is the gentle, penetrating.

• second son and second daughter, as water and fire, are the abysmal or dangerous (3), and the clinging, light-giving (6).

• third son and third daughter are symbols of quietude, the mountain is keeping still, restful (4), third daughter, the lake, is the joyous, joyful (5).

(Wilhelm/Baynes, 1950: l-li)

These eight graphics, with their rich symbolism, constitute the basic energies that operate both in the cosmos (nature) and in the human world, as physical as well as psychic realities (They somehow are parallel to the Five Agents, some are duplicates, like water and fire.)

At a later stage still, the eight trigrams were multiplied by themselves, each one superimposed on all the others, thus forming a total of 64 symbols, called hexagrams (graphics consisting of six lines). These 64 were then interpreted as graphic expressions of the whole of reality, including the human world of action and all situations that could arise in life.

When the yin-yang philosophy emerged, it was also applied to the Yi ching: a whole line was seen as yang; a broken line as yin. Trigram (1) was seen as full yang (three whole lines); trigram (8) as full yin (three broken lines). This addition of yin-yang philosophy enriched the Yi ching commentaries (called ‘Ten Wings’), the sacred book (ching) was complete.

Far from being a divinatory oracle, it had now become a book of deep wisdom that could be consulted for appropriate action in each difficult situation. One can either throw three coins (six times) to obtain a particular hexagram or use milfoil (yarrow) sticks in a more complicated manner to obtain the same result. Once an answer is obtained (a particular hexagram), one reads and studies the commentaries, and finds an answer to one’s doubt or question. Because the text is often mysterious, one must be mentally still and meditate on it. But the results can be surprisingly accurate.

Both Confucians and Taoists have evaluated the Yi ching. The commentaries contain both Confucian (ethical) viewpoints and Taoist (cosmic) interpretations. Today, Taoist priests use the classic for private consultation with their clients; in Western circles, each individual can perform a personal ritual for guidance in the complex situations of life. Publications of the Yi ching and interpretations are numerous. One of the best translations now available was written by Wilhelm, translated into English by C. Baynes (see Wilhelm/Baynes, 1950).

YIN-FU SCRIPTURE (Yin-fu ching/Yinfujing). A short Taoist text of unknown authorship and uncertain date, that had, however, a great influence on the Taoist tradition. Its full title, as recorded in the Taoist Canon (CT 31, TT 27), is Huang-ti Yin-fu ching. It is included in the first part of the canon, in the Tung-chen section. It consists of about 400 characters, divided into three parts. The canon contains 20 commentaries on it.

Although the author is unknown, there has been much speculation about the authorship and the time of its composition: Some have said it dates from the Warring States period, others prefer the Chin dynasty (265–420); others believe it was written by K’ou Ch’ien-chih of the Northern Wei, or during the T’ang period. It appears that inner criticism is not helpful in settling the matter.

Therefore, it is better to focus on the contents, for that is what attracted so much attention. In summary, it says that in the revolution of heaven and earth, the transformation of yin and yang, and in human affairs, there is a relationship of mutual generation (stimulation) and mutual control. The sage must carefully observe the Way of heaven and follow heaven’s action in order to grasp the inner mechanism of heaven and humanity’s correspondence. Then, in ruling the country and nourishing life, all will obtain their benefits: This is the firm foundation of the ten thousand transformations. All through history, both Taoists and Confucians have had a high regard for this text, comparable with the TTC and the Chuang-tzu (TTTY: 29).

YIN-YANG WORLDVIEW. It may also be called a philosophical system, because it sets out to interpret reality and its operations in terms of two polar concepts, yin and yang, which are not only mental concepts, but also powers inherent in all things. Both as mental categories, by which reality is categorized, and as inherent powers in things or energies constituting things, yin and yang are polar extremes, competing and harmonizing in continuous transformation, but ultimately blending into harmony.

The creation of these two terms, yin and yang, is one of the most genial expressions of the Chinese mind. Whether derived from observation of natural phenomena or arrived at by abstract speculation, their universal acceptance into all domains of knowledge and practice had a unifying effect on the overall Chinese world-view. Being the brain child of the Yin-Yang School of Tsou-yen (third century BCE), it was eventually accepted by and incorporated into all systems of Chinese thought, Confucianism and Taoism alike. What the Taoists especially liked in it is its similarity to and compatibility with its own view of cosmic transformation. An example is found in the TTC (Chapter 40): The Tao or the One produced the Two, etc. One can see the easy identification of the “Two” with yin and yang, which in turn give birth to the myriad beings. All things are produced by the interaction of yin and yang. They are also made of yin and yang energies. That shows the complexity of the system and, as will be shown later, the infinite possibilities of application.

The terms yin and yang are used to categorize the universe by arranging all things into two polar camps. That, of course, is a rationalization, but it helps to create order in our minds when we try to understand the origin, constitution, and operations of the world in which we live.

One wonders how it all started. Although the system was finalized by Tsou Yen and his School of Naturalism (which also developed the Five Agents System), the elements of yin and yang were certainly present in much earlier culture, perhaps already in the beginning of the Chou kingdom.

It is most likely that the yin-yang dualistic worldview started as a simple pair of opposites, gradually gained momentum, and finally “conquered” all aspects of Chinese thought. The exact historical process of development is impossible to reconstruct, but at least the starting point seems to be clear.

Originally, Yin signified: dark, shady, cloudy.

Originally, Yang signified: light, bright, sunny.

The first extension was geographic:

Yin is the dark, shady side of a hill (north side) or the dark bank of a river (south side);

Yang is the bright side of a hill (south side), or the bright riverbank (north side).

Further extensions embraced heaven (bright), its generative power, the sky; and earth (dark), its life-giving power, the soil. The pair sun and moon was a natural result.

Since heaven and earth were seen as the cosmic pair of generation and production, it was an easy step to apply this to the human pair: father-mother, husband-wife, male-female. Further: ruler, king, superior (son of heaven), and subject, official, inferior.

New extensions related to natural phenomena: Yang was summer and spring (bright seasons), sunshine, heat, dryness, but also activity, movement. Yin was winter and fall (dark seasons), rain, coldness, wetness, but also rest and tranquillity.

What is bright (yang) is also high, manifest, open, visible, public, and full; it is rationality, reason. What is dark (yin) is low, hidden, mysterious, closed, invisible, private, and empty; it is emotion, feelings, intuition. Here we see the yin-yang dualism applied not only to natural phenomena, but to the human psyche as well; a new, especially Taoist, confirmation of macro- and microcosm interaction.

Further extensions related to the physical body, health and medicine: distinctions are made between yang sickness (fever) and yin disease (cold), yin and yang pulses, yin and yang medicine, yin and yang food.

Perhaps most important in Taoist practice is the distinction of yin-ch’i and yang-ch’i, two types of vital energy vitalizing body and mind. Applied to the concept of soul, there is a yin soul (p’o) and a yang soul (hun), each responsible for different aspects of human life, physical and/or mental, spiritual.

Applied to the “spirit” world: the realm of the gods/goddesses and ancestral spirits is yang, the realm of the dead, the residence of “dead” souls, is yin. Finally, yang is the realm of life, is good; yin is the realm of death, and because most humans hate death, it is seen as bad. But that is a popular interpretation only; originally, yin and yang were both equally good; only an imbalance between the two is seen as not good.

In Taoist spirituality, it is often claimed that practitioners attempt to transform their yin energy into yang energy in order to reach immortality. But that is ambiguous, because it implies that yin energy is not good and an obstacle to progress.

The yin-yang worldview has its applications in all fields of human knowledge and human action, yet yin and yang are relative concepts, never to be taken in an absolute sense. The two are in continuous interaction and change into each other, like night and day are in ceaseless motion, as winter and summer, rest and activity continue to rotate. Except for their application in the area of religious concepts, yin and yang are both essentially good, equally necessary to bring balance to the world, the human body and mind. If “man” is categorized as yang and “woman” as yin, this is not in an absolute sense: Both man and woman need yin and yang qualities to reach harmony and perfection.

Often one sees comparisons of yin and yang as “negative” and “positive.” This is as misleading as the good-and-evil dualism. If yin and yang are dualistic, it is not in an absolute sense. They are relative to one another, as two extremes of one continuum. Combined, yin and yang are the Supreme Ultimate, the oneness that combines all opposites. (See also Five Agents System.)

YÜ CHI/YUJI. Name of a famous fang-shih at the end of the Han dynasty. He was a native from present-day Shantung. According to a record in the Hou-Han shu (“Latter Han History”), he obtained a “spiritual book” in 170 scrolls (chapters) at a place named Ch’ü-yang. The title was T’ai-p’ing ch’ing-ling shu, and the book is an early version of the important Great Peace Scripture. It is said that his disciple, Kung Ch’ung, took it to the capital and presented it to Emperor Shun (r. 126–144 CE).

There is a report about (another?) Yü Chi from the Three Kingdoms period who lived in east China. He burned incense and studied Taoist books and made talismanic water (fu-shui) to cure illness. He had a great following in the southern kingdom of Wu; many chose him as their spiritual master. One day he went to the headquarters of Sun Ts’e, the ruler of Wu, where a great number of officers believed in him: They left the banquet table and went to pay their respects to Yü Chi. Angry with spite and jealousy, Sun Ts’e had him executed, his head was put on public display as a warning. Although Yü Chi was no threat to Sun Ts’e’s political authority, he was probably seen as some kind of personal threat.

The story is not finished yet. After his execution, his followers continued to worship him and to pray to him to intercede for their good fortune, saying: “The Master Yü Chi is not dead! His mortal flesh has decomposed and he has become [an immortal] “sylph”! (Tsukamoto/Hurvitz, 1985: 473–4). (The parallel with Jesus’ execution and resurrection is fascinating!)

YÜ-HUANG CHING See JADE EMPEROR SCRIPTURE

YÜ-HUANG TA-TI See JADE EMPEROR

YÜ-PU See STEP(S) OF YÜ

YUAN-SHIH T’IEN-TSUN/YUANSHI TIANZUN (Heavenly Venerable of the First Origin, or of the Original Beginning). Title of the Supreme deity of Taoism, the highest of the triad of T’ien-tsun or Three Pure Ones.

He is also called Yü-ch’ing (Jade Purity) Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun. His emergence in Taoist scriptures is later than that of T’ai-shang Lao-chün (Lao-tzu deified), whose cult goes back to the second century CE. Even as late as the time of T’ao Hung-ching, Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun had not yet reached the top position. In T’ao’s pantheon, he is the foremost deity of middle rank.

Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun is believed to have existed before the creation of the universe and its 10,000 beings. He is eternal, imperishable, whereas the universe goes through cycles of creation and destruction. When a new creation of the universe takes place, he descends to earth to reveal to mankind the secrets of the Tao.

His residence is above all the heavens, at the top of the Three Worlds (Ta-lo t’ien), called “mysterious city jade capital.” It is built of marble; its palaces consist of seven jewels. Those who dwell in this city are immortals of various ranks who do not perish whenever the universe comes to an end.

Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun is not worshipped in isolation, but always as the central member of the trinity. Statues of these three are found only in Three Pure Ones temples of Taoism. The Taoist Canon contains several scriptures on Yuan-shih T’ien-tsun (MDC: 71).

YUEH-FEI YUAN-SHIH/YWEFEI YUANSHI (Primal Teacher Yueh-fei). A famous Sung general, deified after his death and enthroned in the Chinese pantheon, he is also being worshipped by the Taoists, sometimes together with Kuan-kung, Lü Tung-pin, and others, as the Five Lord-Benefactors.

In the service of the Sung dynasty, he battled against the invading Chin and Mongol armies, until he became the victim of a jealous prime minister; he was jailed and executed when he was only 39 years old. His cult spread among the people during the Ming and Ch’ing dynasties, and even today, 11 temples are dedicated to his worship in Taiwan, especially in the counties of Chiayi and Tainan. In some temples, one can see murals representing his mother tattooing on his back four characters: “single-minded loyal, dedicated to the country” (see TMSC: 32).

YÜN-CHI CH’I-CH’IEN/YUNJI QICIAN (“Seven Lots from the Cloud Bag”). An important Taoist compendium (or collectaneum), in 122 chapters, compiled by Taoist master Chang Chün-fang (fl. 1008–1029) during the Northern Sung. Although still published today as a separate work, it has also been included in the Ming Taoist Canon (CT 1032, TT 677–702, in the T’ai-hsuan supplement).

Chang Chün-fang was in charge of the new edition of the Sung Taoist Canon, published in 1019, but on orders of Emperor Chentsung (r. 993–1022), he prepared the Yün-chi ch’i-ch’ien as a personal reference work to provide “bedtime reading” for the emperor (J. Boltz, 1987: 230). However, the collection was only finished in 1028 or 1029, and was then presented to Emperor Jen-tsung (r. 1023–1063).

This compendium is not exactly an abridged version of the Taoist Canon (the texts on liturgy are missing), but is an invaluable source of information on earlier texts (Six Dynasties and T’ang periods) and thus gives insight into the “founding years of early revelatory traditions” (Boltz: 231).

Besides the opening chapters, dealing with cosmogony and scriptural transmissions, the subjects covered are “cosmology (Chapters 21–22), astral meditation (Chapters 23–25), topography of sacred space (Chapters 26–28), birth and destiny (Chapters 29–31), hygiene, diet, and physical therapy (Chapters 32–36), codes of behavior (Chapters 37–40), ritual purification (Chapter 41), techniques of visualization (Chapters 42–44), additional instructions on the cultivation of perfection and miscellaneous applications (Chapters 45–53), control of the vital forces of the body (Chapters 54–55), embryonic respiration (Chapter 56–62), chin-tan/nei-tan (Chapters 63–73), prescriptive pharmaceuticals (Chapters 74–78), talismans and diagrams (Chapters 79–80), keng-shen lore (Chapters 81–83), shih-chieh or corpse liberation (Chapters 84–86), theoretical issues, such as whether divine transcendence can be learned (Chapters 87–95), selections of verse (Chapters 96–99), chronicles (Chapters 100–102), and hagiography (Chapters 103–122)” (Boltz: 231).

This rich work of Taoist literature deserves translation, but it would be an arduous task. Instead, it is often quoted in scholarly studies, and shorter extracts have been translated. (For a further discussion, see J. Boltz, 1987: 229–231.)