CHAPTER TWO

BEYOND THE LINE

Good Eolus be friendly now, and send a happy gale,

That Captain Drake and all his men on seas may safely sail;

And God that guides the heavens above, so prosper thee mayhap,

That all the world have cause to say, thou liest in Fortune’s lap.

Henry Roberts, A Most Friendly Farewell, 1585

EVEN AS DRAKE’S little bark was shuffling back and forth across the Channel, the troubles that had afflicted England were tearing the nations of Europe apart. Among the literate and influential classes within reach of the Calvinist propaganda that flooded from Geneva a new faith grew apace. The winds of Protestantism were sweeping the breadth of the Continent, and one by one the kingdoms fell before them. Elizabeth established a Protestant church in 1559. Beyond the North Sea Sweden did likewise. In Germany the reformers gained the upper hand. France was plunged into a civil war in 1562, and while the monarchy became a brickbat between the hostile factions the Calvinist churches threw their influence behind the Prince of Condi and against the Catholic Guises. The Netherlands, which were then ruled by Catholic Spain, saw the maturation of another alliance, this time between Protestantism and aggrieved Dutch nobles who complained that their former liberties were being curtailed. Divided among themselves the Protestant churches may have been, but to the orthodox this tide was fearful indeed. ‘In many countries,’ sighed a Venetian, ‘obedience to the Pope has almost ceased, and matters are becoming so critical that if God does not interfere they will soon be desperate.’1

From Orthodoxy’s inevitable response to this gigantic crisis grew what later centuries called the Counter-Reformation. Catholicism strove to dam back the tide threatening to engulf it, both by raising its own performance and by resisting heresy by force. In lengthy debate the Catholic bishops at last clarified their own faith and put it upon a more defensible and efficient footing, but their counter-stroke looked beyond a mere reform of the Catholic Church towards a battle in which power and arms would be decisive, a battle in which one man above all others would stand as the mainstay of the papacy and orthodox religion – the mightiest monarch in Christendom, Philip II of Spain.

Philip was a little under thirty years of age when he succeeded his father to become King of Spain and its wide dominions in 1556. His inheritance was vast: principally, Spain itself, the Netherlands, part of Italy, and most of the new territories of South and Central America. In some respects Philip was not unlike the man Francis Drake was becoming. He, too, wove the interests of God and country into one, and believed himself an instrument of both. Drake was to emerge as a Protestant hero for the new England Elizabeth was forging; Philip no less earnestly promoted the Catholic faith, hoping to protect his people from the fate that ultimately met all heretics and to advance the country’s imperial ambitions at the same time. But apart from the undoubted energy and religious zeal that propelled both men, there were few other parallels between the mean Devonshire seaman and the powerful king. Where Drake grew bold, confident and decisive, Philip was tortured with indecision and self-doubt, agonizing over each move he made. Where Drake was bluff and charismatic, Philip felt secure only among his books and papers. He was awkward and uneasy in company, an aloof, almost reclusive figure, whose secretive manner, impassive countenance and whispering voice disconcerted rather than engaged those with whom he worked. While Drake swaggered his decks, gregarious and assertive and full of cheer, lonely Philip toiled night and day at his desk, filling the margins of the countless papers that passed before him with a wandering scrawl that testified that few details escaped the king’s attention. In his solitude, too, he dwelt upon the private tragedy of his life. By 1570 he had been thrice married (once to the English queen, Mary Tudor) and thrice widowed, and his only heir had been Don Carlos, so vindictive, so idiotic and irresponsible an heir that he was imprisoned by the order of his own father. When Don Carlos died in custody malicious tongues accused the king of his murder.

Whatever his personal life may have been, Philip was a dutiful king with an astonishing capacity for work. He attempted to deal as justly with his people as he knew, and strove for the imperial and national integrity of his country. Partly because of it, his relations with the papacy were turbulent. The popes relied upon Philip, but they seldom trusted him, fearing that religion was for him a convenient mask for secular, and, as they saw it, baser ambitions. Nevertheless, both parties needed the other. Without the strength of Philip, the Counter-Reformation lacked teeth. For his part, Philip was a devout Catholic, determined to unite his dominions beneath one faith, and he relied heavily upon the enormous subsidies the papacy awarded him as well as the authority with which the Pope’s support invested Spain’s undertakings.

Although Spain’s traditional European rival, France, was in eclipse, the advance of heresy in the north posed an additional unwanted burden upon Philip. He was already championing Christendom against the Turks in the Mediterranean, and the Moors in the south of his own country were not crushed until 1570. After the loss of forty-two vessels in an attack upon the island of Djerba in 1560, it took Philip four years to rebuild his Mediterranean galley fleet. Gradually he restored Christian supremacy, but only in 1571 did his naval victory at Lepanto succeed in deflecting the Turks eastwards to easier conquests away from Europe. No, to commit himself to a war against Protestantism at a time when the forces of the Ottoman Porte remained unchecked on the other side of the continent was not the easiest decision for a monarch as diffident as Philip.

Yet Philip was convinced that political unity within his territories depended upon religious unity. Not for him was the path of toleration. He rooted out embryonic Protestantism in Spain and censored its literature, and he supported the Inquisition’s terrifying purge of heretics. In 1567 he ordered an army under the Duke of Alba into the Netherlands to restore it to order, and declared, ‘I have preferred to expose myself to the hazards of war … rather than allow the slightest derogation from the Catholic faith and the authority of the Holy See.’ But to effect his purpose he needed money.2 Spain possessed the finest troops in Europe, the dreaded Spanish tercios, but these were the minority of the soldiers Philip required for his formidable undertaking. For the rest he must rely upon mercenaries – Italians, Walloons and Germans – whose fidelity depended upon the reliability of the paymaster. And Spain had been bankrupt as recently as 1557. Although the Crown drew no less than four-fifths of its revenue from Castilian taxes and papal subsidies, Philip’s offensive in the Netherlands rested substantially upon another source of income, the silver that was ponderously shipped across the Atlantic from the Americas.

Spain’s discoveries in the New World had been the remarkable fruits of the quest for the riches of Eastern trade, which Columbus had hoped to tap by sailing west, and were developed by men hungry for minerals and treasure, for glory and adventure, for prestige and the souls of the pagans. By virtue of Columbus’s discovery of the West Indies in 1492 Spain claimed a monopoly on the exploitation of the Americas, just as her imperial rival, Portugal, set up similar pretensions upon the Indian Ocean after her voyagers had sailed around the Cape of Good Hope. In an effort to mark the boundaries of the two empires, in 1493 Pope Alexander VI issued papal bulls dividing the new territories and conferring on Spain the right to the Americas. And by the Treaty of Tordesillas the following year Spain and Portugal recognized their respective monopolies, the former’s in the west and the latter’s to the east.

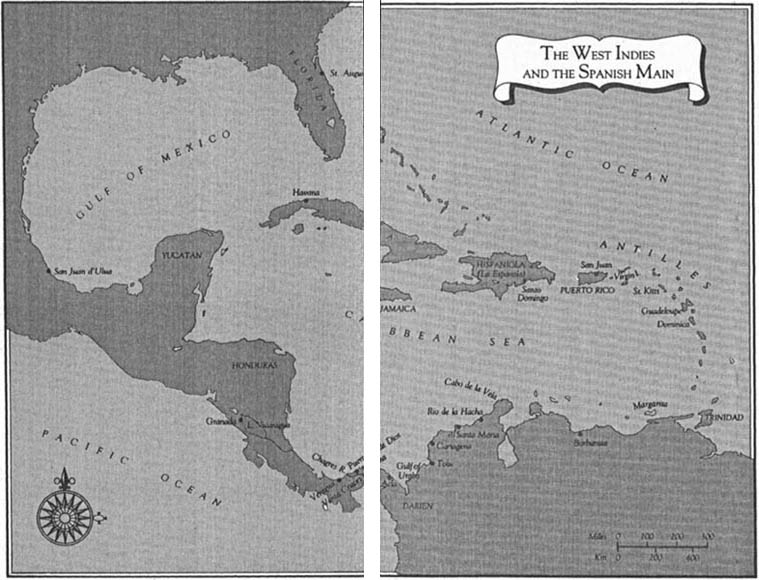

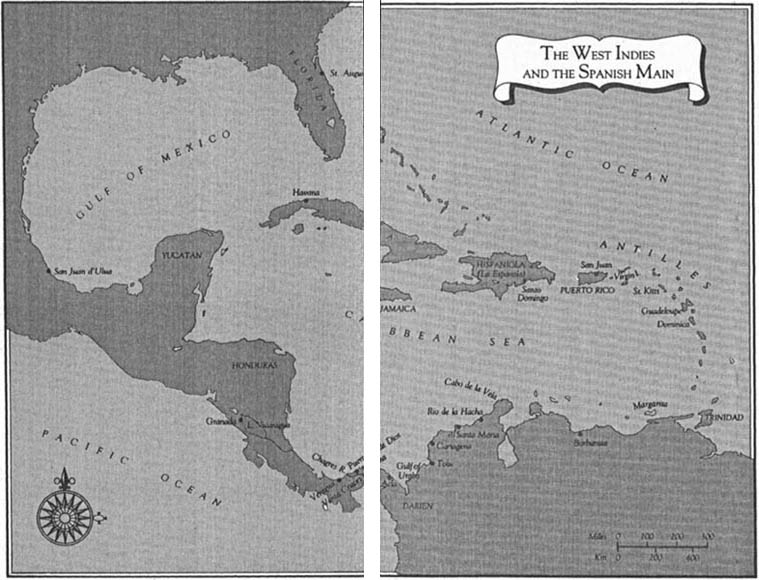

The pace and character of Spanish expansion were the stuff of heroic legend. It soon became obvious that the new lands in the west represented not part of the East Indies but a continental land-mass between Europe and Asia. In the first decades of the sixteenth century Spanish expeditions had conquered and pillaged the native civilizations of Mexico and Peru and circumnavigated the globe. From the West Indies Spanish settlement filtered into mainland South and Central America, and a colonial administration was established under the jurisdiction of two viceroys, one in New Spain (Mexico) and the other at Lima in Peru. Important if rudimentary towns developed, Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola, Havana on Cuba, San Juan on Puerto Rico, Panama and Nombre de Dios on the isthmus of Panama, and Cartagena on the Caribbean coast of South America, the legendary Spanish Main itself. A ranching, planting and mining economy produced hides, sugar, ginger and – above all – treasure.

Europe was tantalized not so much by the feat of discovery and colonization itself as by the fabulous wealth upon which the Spaniards stumbled. In 1545 rich silver deposits were located at Potosi in what is now Bolivia and three years later more at Zacatecas in Mexico. By the 1560s, when Drake first saw the Caribbean, the mines were producing upon a large and regular scale, and a transatlantic trade between Seville and the New World had emerged. Spain sent two fleets, or flotas, a year to America, perhaps as many as seventy vessels in convoy, carrying goods the colonies needed – food, clothing, wine, oil and equipment. The annual Mexican flota left Seville in the spring, bound for Vera Cruz. A few months later the Panama flota followed, but it headed for Nombre de Dios on the isthmus of Panama, unloading its exports before wintering in the sheltered harbour of Cartagena on the mainland. In the following spring it returned to Nombre de Dios to collect silver which had been brought from Peru, and at Havana united with the homeward-bound Mexican flota for the return, under escort, to Seville.

Between 1556 and 1570, 40 million ducats of silver were brought into Spain. The arrival of the annual treasure fleets was always an occasion of great importance, not only for Spain but for Europe in general. Some of the silver paid merchants for the goods they had exported to the Americas, but about two-fifths of it went to the Spanish Crown, forming upwards of 11 per cent of the king’s total revenue. It was essential to Spain if she was to meet her gigantic commitments in Europe, for it redeemed the country’s debts to the German and Genoese bankers whose credit kept Philip’s army of mercenaries in the field.

Such a lucrative system symbolized as well as maintained Spain’s prestige, and inevitably aroused the envious attention of foreign nations. The Spaniards acknowledged that their colonial trade could not entirely exclude the foreigners, and granted licence to Portuguese merchants to enable them to participate in it upon the payment of appropriate taxes. Despite the provision, however, an unregistered contraband trade soon flourished, and slaving became one of the worst features of it. The new American economy was labour intensive, and Portuguese slavers found a ready demand for the unfortunate blacks they shipped from Africa, an area within the monopoly claimed by Portugal. From the 1520s French corsairs also appeared in the Caribbean, extending the warfare between France and Spain to the New World, and their boldness increased. In the 1550s they captured Havana and Cartagena.

By the time Drake appeared in the West Indies, the Spaniards had already confronted two waves of interlopers: the illicit traders, usually Portuguese or French, and the French freebooters. Efforts had been made to strengthen defences, but they had been only marginally successful. One problem lay in the lack of an effective central control able to co-ordinate and support local defences. The West Indian islands, Florida, and part of the Spanish Main were administered by the Audiencia of Santo Domingo; that part of the Main east of the isthmus of Panama as far as Rio de la Hacha fell within the jurisdiction of the Audiencia of New Granada at Santa Fé de Bogotá; Panama had its own Audiencia, but while it was ultimately accountable to the Viceroy of Peru areas to the north-west effectively fell beneath the control of the Viceroy of New Spain in Mexico. Confronted with highly mobile adversaries flitting about the coasts in swift, small-oared ships, it is not surprising that the Spanish colonies met the attacks with difficulty.

The towns of the Caribbean also remained woefully vulnerable, their scant fortifications ill equipped with artillery and soldiers. For their defence they relied primarily upon a feeble, badly trained and under-armed militia. Before 1560 only Santo Domingo could muster more than two hundred white militia, and excessive reliance had to be placed upon blacks and American Indians whose fidelity to Spain was very understandably in doubt. Few of the defenders possessed long-range weaponry such as matchlocks or crossbows, and most were armed only with pikes or swords. At sea Spain made an earnest attempt to respond to the threats to the Caribbean by appointing as commander of a new Indies fleet of twelve galleons Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, who had just driven a presumptive French colony from Florida; his orders were to suppress the corsairs, but his boast ‘that no corsair shall come to these parts without being lost, nor any ship trading without licence’ was scarcely fulfilled.3 His ships were built in the winter of 1567–8, but three were lost before they reached the Americas and the balance, when they were not being withdrawn for convoy duty with the flotas, proved incapable of catching the light-draught privateers employed by the French. In 1570 Menéndez was ordering eight small frigates for service with his squadron, so dissatisfied was he with the force at his disposal.

Too often defence remained local in character, dependent upon the resources of private individuals, and lacking the direction the Crown might have given it. Nor did the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, which ended hostilities between France and Spain in Europe in 1559, bring peace to the Caribbean. The corsairs adhered to the view that, west of the line established at the Treaty of Tordesillas, an imaginary boundary 370 leagues west of the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands, the regulations governing European relations were not applicable. In the words of a phrase which has continued to engage historians, there was to be ‘No Peace Beyond the Line’.

After his invasion of the Netherlands in 1567 Philip II was only too painfully aware of the importance of his American silver, for it dazzled all Europe and guaranteed his credit, but he believed that the precious treasure fleets would be adequately protected by the convoy system he had established even if a more general defence of the West Indies remained difficult. His richly laden silver ships continued to plod relentlessly across the Atlantic. However, a new and potentially more dangerous adversary had recently crossed the line – an English squadron this time, under the command of that Plymouth shipowner, Master John Hawkins.

Although a race of islanders, the English were late contenders for world-wide empire. They were a maritime nation, it was true, but throughout the early sixteenth century they had been content to watch their export trade in woollen cloth expand in Europe and leave bolder overseas adventures to others. John Cabot, it was also true, had left Bristol in 1497 and discovered Newfoundland or Nova Scotia for England, but nothing had grown from it except periodic fishing off the Canadian banks. Similarly, although Henry VIII had been sensible of the importance of controlling the English Channel and had created a powerful navy, servicing his ships in royal dockyards at Portsmouth, Woolwich and Deptford, that force had not invariably been kept up to strength. When Drake was but a child the number of ships of 400 tons or more in England’s navy had fallen from twelve to three. But in the 1550s the pace of the country’s overseas activity sharpened. Her cloth trade, funnelled through Antwerp, was faltering, and the London merchants wondered whether they had depended too heavily upon one market and what opportunities might exist for diversification; the East, from which Portugal was reaping such riches with trade in luxuries like pepper, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves, camphor, teak, silk, sandalwood, copper and porcelain, grew more alluring; and the government during the reign of Edward VI was ready with encouragement. But in England’s first surge overseas there were many casualties. Sir Hugh Willoughby and his crew froze to death aboard their ship in the wintry seas off Lapland, while Thomas Wyndham and most of his men perished of a fever on the pestilential coast of Benin. Nor was the process without diplomatic entanglements. Portugal protested as English ships nosed along the African coast, asserting her exclusive right to the area by virtue of discovery and conquest, and Spain stood ready to raise her voice when John Hawkins threatened to extend England’s operations to the West Indies.

Hawkins’s expeditions beyond the line added another dimension to the growing difficulties between Spain and England. Philip was already prepared to believe that the English had encouraged the Dutch rebels, and he knew that their privateers had taken commissions from the French Huguenots to attack Catholic shipping in the Channel. As yet the tension had its limits. On opposite sides of the religious divide though they were, Philip and Elizabeth had no desire for war. They both feared France too much to sacrifice a potential ally; their countries enjoyed some profitable trade; they had their hands full already, Elizabeth with Scotland, France and Ireland, Philip with the Mediterranean and the Netherlands; and neither had the resources to prosecute another major conflict. But John Hawkins’s penetration of the blue waters of the Caribbean opened another rift between them, one which would deepen as the years passed. The integrity of the Spanish American colonies would be an issue between the two monarchs as long as either of them lived.4

John Hawkins bore a famous name. Born about 1532 of a family that hailed from Tavistock, he was often said to have been cousin to Francis Drake, but although we know from a letter of Hawkins’s elder brother that there was a blood connexion between the two famous sailors, its exact nature is unknown. It was certainly sufficient to induce the Hawkins brothers to employ young Francis in a position of responsibility. John came of an enterprising seafaring stock. His father was William Hawkins, one of the few English merchants who had challenged Portugal’s supposed monopoly of the African and Brazilian trades. In the 1530s he had developed a triangular run, trading in Africa for ivory and other commodities, and crossing the Atlantic to barter with the natives of Brazil. In these and other ventures William Hawkins had been successful, and he became one of Plymouth’s leading dignitaries, serving the town as both mayor and Member of Parliament. More tangible than this prestige, he also bequeathed to his sons, William and John, a fleet of privateers and merchantmen. Of the brothers it was John who emerged the more dynamic. He strutted in his extravagant dress and charmed the peers and diplomats of the court, but he was for all that a hard-headed, shrewd, calculating and methodical businessman, articulate and intelligent, and when Drake first sailed for him he had the assuredness of one who was at home on sea and land and had twice been out beyond the line.

About John Hawkins’s voyages there has been great controversy. They were slaving voyages, the first in English history. Between 1562 and 1565 he had commanded two expeditions to Africa, where he acquired a few hundred Negroes and sold them to the Spaniards in the West Indies for American produce such as hides and treasure. Posterity has handled Hawkins roughly over the matter of the slaving, and not without reason. It was an inhuman trade, less offensive perhaps to the blunter sensibilities of the sixteenth century than it would be to us, but undeniable in its brutality to any but an insensitive observer. These objections do not seem to have troubled Hawkins or his backers, who simply asked that the colonial products brought back to Europe reap a sufficient profit. And among those backers were the highest in the land: London merchants like Sir Lionel Ducket and Sir Thomas Lodge; naval officials like Benjamin Gonson, William Winter, and the Lord Admiral of England; courtiers of the stamp of the earls of Leicester and Pembroke; and the queen herself, who contributed the 700-ton Jesus of Lubeck to Hawkins’s second voyage.

Concern was expressed, however, at the diplomatic repercussions of these incursions into territories claimed by Spain and Portugal. The latter protested loudly that the African trade was her own, and alleged that Hawkins had even resorted to piracy, seizing slaves and other cargoes from Portuguese ships off the coast of Sierra Leone. In reply, the London merchants as vociferously denied that Portugal could exclude others from areas she had neither sufficiently subjugated nor occupied. Spain, too, denounced the voyages, embarrassed that her own West Indian colonies should profit from and perhaps collude with the interlopers. By Spain’s imperial regulations the activities of Hawkins were plainly illegal. He entered the Caribbean without obtaining a licence to trade from Seville. He carried goods which had not been registered at Seville. And while he was ‘trading’ he refused to pay the local imposts upon the importation of slaves. The point was made several times, but Elizabeth chose to demonstrate her independence of Philip by ignoring his complaints about her seamen, and the voyages continued.

The Spanish Crown ordered its officials in the Caribbean not to treat with the English, but the colonies wanted slaves, and it is difficult to decide how far their resistance to Hawkins was genuine. Hawkins’s practice was to demand a licence to trade from these officials (a licence which was in any case invalid since it was not issued in Spain) and to enforce trading by threats and a show of force. The procedures were exemplified by the case of Rio de la Hacha, a pearl-fishing and mining centre on the Spanish Main. The town was administered by a royal treasurer, Miguel de Castellanos, and when Hawkins arrived in 1565 the Spaniards refused to deal with him, having been expressly forbidden to do so by Santo Domingo. Nonetheless, ‘trading’ took place. Hawkins landed some men, dispersed the few Spaniards who turned out to resist him, and compelled Castellanos to be reasonable. But the Spanish show of resistance was unconvincing. In Spain it was said that Castellanos had colluded with the English, and that the fight had been a mere sham, designed to colour the treasurer’s claim that his hand had been forced. Whatever the truth, poor Castellanos cannot have been ignorant of the rumours being spread about him, nor of the knowledge that one of his colleagues at Borburata had been arrested and sent home to face charges of trading with the English. The treasurer resolved that if Hawkins showed his face again Rio de la Hacha would demonstrate its loyalty to the Crown beyond doubt.

Young Francis Drake was inspired by the exploits of John Hawkins. These voyages into far seas, bearding the Spaniards in their own waters, promised excitement as well as profit. The doubts about the reception further English ventures would receive in the Caribbean, if they troubled him at all, possibly merely sharpened his interest, for he was an adventurous and fearless youth. He knew that Spain was protesting volubly to the queen, but Hawkins held the noise in small regard and soon had a further enterprise in hand. It is to be imagined that it was to Drake’s unlimited pleasure that Hawkins signed him up for the very next voyage beyond the line.

The meagre details that survive of Drake’s début in the Caribbean are instructive. One of his shipmates on the expedition was a Welshman, Michael Morgan, described as a stout, short man with a ruddy freckled complexion, from a farming family of Cardiff. He was in his mid-thirties and several years Drake’s senior, but something of a waster. An experienced seaman with voyages to Lisbon, La Rochelle and Brittany behind him, Morgan was the father of two children, although he had lost his wife. Nevertheless, he was penniless when he joined the new Hawkins venture, having gambled away all that he had. From such an unlikely witness comes one of the first and most revealing glimpses of the young Drake. Regrettably the information was preserved through unpleasant circumstances, for Michael Morgan eventually fell into the hands of the Spaniards and suffered the tortures of the rack in Mexico City in 1574. In the resultant confession he admitted that it was Francis Drake who had converted him to Protestantism on the voyage of 1566–7. The full account is given here for the first time:

He said … although at that time he [Morgan] could have found a priest to whom to confess he did not confess but to God in his heart, believing that such a confession was sufficient to be saved, and this he had heard said by Francis Drake, an Englishman and a great Lutheran, who also came on the vessel and who converted him to his belief, alleging the authority of St Paul and saying that those who did not fast should not say evil of those who did, and those who fasted should not speak evil of those who did not, and that in either of those two doctrines, that of Rome and that of England, God would accept the good that they might do; that the true and best doctrine, the one in which man would be saved, was that of England … On the deponent [Morgan] asking the said Drake whether his parents and forefathers would be lost for having kept the doctrines of Rome, he replied ‘no’, because the good they had done would be taken into consideration by God, but that the true law and the one whereby they would be saved was that which they now kept in England.5

The discussion involved only the two men, but it was evidently not the last they enjoyed upon that subject, for Morgan added that ‘the said Francis Drake had taught him the Paternoster and Creed of the Lutheran Law and that he had also learned to recite the Psalms from a book.’ Thus did the young sailor, fired by his zeal for the reformed church, employ the talents of his father and his own natural eloquence to bring an older man to embrace his simple faith.

If Drake went forth a strong and forthright Protestant, estranged from the Spaniards by his theology and the memories of his unsettled childhood, the voyage upon which he now embarked left him with more personal grievances against the servants of Philip II, and in it can be traced the roots of that deep enmity Drake held towards Spain for the rest of his life. The expedition was an unlucky one, and it sailed under a cloud, for Elizabeth had bent before Spanish protests about the earlier slaving voyages to the extent of forbidding Hawkins to leave England. But Hawkins was sure enough of his ground to allow his ships to slip out of Plymouth on 9 November, 1566, under a different captain, John Lovell. There were three vessels, the Paul of 200 tons under Master James Hampton, the Solomon of 100 tons under Master James Raunse, and the 40-ton Pasco under Master Robert Bolton. Drake was with them, probably serving as an officer, but upon which ship we cannot tell.

The ships were soon beyond any waters Drake had seen before, running before the prevailing winds towards the Guinea coast of Africa. There, in territory jealously guarded by the Portuguese, Lovell resorted to the pillage with which Hawkins had earlier been charged. At Cape Verde a Portuguese ship laden with wax, ivory, slaves and other commodities was seized by the English. February of the New Year saw Lovell off Santiago in the Cape Verde Islands, where he took two more Portuguese vessels, one reportedly worth 15,000 ducats and laden with slaves and sugar, and another valued at 600 ducats which had left Lisbon for Brazil. The first of these vessels was apparently taken into service by the English, for those of her crew who had not been killed while resisting capture were set ashore. Finally Lovell’s piracy, for it was nothing less, took him to the Isle of Maio and the capture of two prizes with cargoes which were worth, overall, 7,000 ducats, or so it was said. These events illustrated the curious relations that existed among seamen of nations avowedly at peace in Europe once they were in contested colonial waters. The English were repudiating Portugal’s pretensions, and the latter was prepared to defend them by force, capturing or sinking interlopers whenever she could. And lives, both black and white, were cheap in the greedy struggle for trade empire.

Lovell’s attacks on the Portuguese ships were the first naval ‘engagements’ in which Drake had served. Whether they gave Lovell all the slaves he required is not known, but he was soon striking across the Atlantic with his merchandise, heading for the Spanish West Indies. Michael Morgan, our Welsh informant, told the Inquisition that the English visited Borburata on the Main and the neighbouring islands of Margarita and Curaçao, but the contemporary Spanish documents tell only of two contacts with Lovell, at Borburata and Rio de la Hacha.

At Borburata Lovell encountered a like-minded French expedition under Jean Bontemps. It, too, had collected Negroes from the Guinea coast and it had put into Borburata to sell them the day before Lovell arrived. Apparently the French and English conferred with the local authorities and offered to supply one hundred slaves to the royal treasury in return for a licence to sell a further two hundred with other goods. The matter was referred to the governor of the port of El Coro, but he was sensible of the Crown’s attitude to the illicit traders and refused to issue the licence. However, the French, like Hawkins, had their own methods of dealing. Even before the governor’s answer had been received they had seized some of the prominent citizens of Borburata as hostages and were threatening to carry them to France unless the Spaniards co-operated. After the arrival of the governor’s refusal, Bontemps decided to make the best of a bad job. He released his prisoners, but kept 1,500 pesos which had belonged to two of them, and landed in return twenty-six Negroes. Whether Lovell himself benefited from this ‘trade’ and whether he had any other dealings at Borburata the evidence does not reveal.

At Rio de la Hacha Miguel de Castellanos was still fretting over his dealings with Hawkins two years before when the English reappeared. Castellanos had served his town for more than thirteen years. He was then its captain-general and royal treasurer, but he was an ambitious man and apprehensive lest the rumours of his collusion with Hawkins were injuring his credit. Ominously, the Audiencia of Santo Domingo had commissioned a judge to investigate the affair, and whatever the royal treasurer of Rio de la Hacha really thought of Hawkins, he knew that he would have to redeem himself with his superiors if the ‘corsairs’ returned. In May 1567 that day finally came. Bontemps arrived at Rio de la Hacha first, and Castellanos refused him a licence to trade and sent him on his way disgruntled, although not before the Frenchmen had advertised that an English squadron was also coming to the port. Lovell perhaps anticipated a better reception, for it was charged against Castellanos that he had agreed with Hawkins what goods the English would bring on their next voyage. Was Lovell expecting full co-operation, believing that the colonies were hungry for the goods in his ships and that he was fulfilling some kind of verbal contract made between Hawkins and Castellanos? If so, he was rudely awakened. His three ships and Portuguese prize were seen off shore on the eve of Pentecost, and there they remained for two days until Whit Sunday, when the weather admitted Lovell into the harbour. On Monday the captain, or a representative, went ashore to request permission to trade, and to the dismay of the English, Castellanos refused a licence.

Mortified, Lovell remained close by until Friday, uncertain as to how he should proceed, but occasionally sending men ashore to test the resolve of the Spaniards. Still they would not trade. On Friday a final interview with Castellanos failed to move him. According to the Spanish account Lovell asked if he could set some Negroes ashore in return for a receipt from the Spaniards, perhaps hoping that a mere acknowledgement that he had deposited slaves at the town would have given Hawkins a basis to demand payment upon some more auspicious occasion, but the royal treasurer would have none of it. He surmised that the English were not strong enough to coerce him, and he must have known too that Lovell’s Negroes had endured a miserable voyage in captivity and that some of them would have been so ill that if they were not landed they would probably die. In short, the English were in a weak and desperate position.

An hour after nightfall on Saturday Lovell took the only choice open to him. He selected ninety-two of the blacks, old or sick and emaciated, and he set them down on the shore at a place where a swollen river prevented the townspeople from crossing to dispute the landing. Then, leaving the Negroes to fall into the hands of the Spaniards free of charge, he sailed away in the darkness, poorer and wiser, steering along the coast and across towards Hispanìola. Nothing is known of his activities there, but he was back in Plymouth early in September, and it is hardly likely that Hawkins was satisfied with the result. His men had been rejected at Borburata and Rio de la Hacha, compelled to surrender more than ninety Negroes, and may not have made enough money to cover the cost of the voyage.

On the other hand, the officials of Rio de la Hacha were jubilant, and eagerly turned their handling of the English to their advantage. Did it not vindicate them of charges of collusion? Had they not demonstrated their obedience to their king? Indeed, the more they narrated the affair the larger it became. We have recounted the incident of Rio de la Hacha from the earliest reports, but in January 1568 Castellanos and his cronies were sending fresh accounts of it to the Crown and embellishing the story as they did so. Now Castellanos claimed that there had been a gun-battle with the English:

A few days later another large fleet of English galleons and ships appeared, in command of John Lovell, and he made extensive preparations to trade in this town. Seeing that this was not permitted to him, they played many guns upon us, against which we defended ourselves so that we beat them into flight.6

Another version of the defeat of the ‘large fleet’ written about the same time by the town factor, Lazaro de Vallejo Aldrete, and Hernando Costilla, insisted that Lovell had brought his ships in shore and sent his men in four small boats towards a landing place to threaten the town. Although this letter contained no reference to firing, it maintained that the English made several attempts to disembark, but that they were always turned back. But a third revision of the tale, signed by officials of Rio de la Hacha, combined both Castellanos and Vallejo Aldrete and asserted that there had been firing and an attempted landing. This letter had Lovell bombarding the Spaniards from his ships and boats and dispatching the latter towards the shore, and it relates how the attack was repulsed.

Strange it is that the earlier letters contain no reference to these events, and, indeed, that the town expressly stated in its account of 23 June, 1567 that after Lovell had been refused a licence he retired to his vessels ‘where he remained six days without daring to attempt anything further’, and that he then landed his Negroes at night and left.7 That letter does describe how the French had earlier been repulsed in an effort to land, before the arrival of Lovell, and it must be concluded that in their later descriptions the Spaniards conveniently confounded the two incidents in pursuit of political capital.

But English gunfire there was to be in Rio de la Hacha, for as the chastened Lovell sailed wearily for home there was one aboard his ships of greater spirit, and who nursed grievances sorely. Drake had watched impotently as Castellanos had cheated the English, but he was to return, soon.

1 Green, Renaissance and Reformation, 177.

2 Elliott, Europe Divided, 166. For Spain in the sixteenth century see Elliott, Imperial Spain, and Lynch, Spain Under the Habsburgs.

3 Andrews, Spanish Caribbean, 95. Spain’s defence of the West Indies is dealt with by Hoffman, The Spanish Crown and the Defense of the Caribbean. For the flotas, see Chaunu, Séville et l’Atlantique, vol. 3. The great age of discovery generally is examined in Patty, Age of Reconnaissance.

4 English overseas expansion of the period is covered by Williamson, Age of Drake; Ramsay, English Overseas Trade; Quinn and Ryan, England’s Sea Empire; and Andrews, Trade, Plunder and Settlement.

5 Confession of Michael Morgan, January 1574, Conway Papers, Cambridge University Library, Add. MS 7235.

6 Castellanos to the Crown, 1 January, 1568, Wright, ed., English Voyages to the Caribbean, 107. This volume publishes the relevant Spanish documents for Lovell’s voyage. English accounts are summarized in Williamson, Sir John Hawkins, 122–6, and the same author’s Hawkins of Plymouth, 93–9.

7 City of Rio de la Hacha to the Crown, 23 June, 1567, Wright, 95–100.