CHAPTER SIXTEEN

‘STOP HIM NOW, AND STOP HIM EVER!’

Whether to win from Spain that was not Spain’s,

Or to acquite us of sustained wrong,

Or intercept their Indian hoped gains,

Thereby to weaken them, and make us strong.

Charles FitzGeffrey, Sir Francis Drake, 1596

TIME WAS RACING now, headlong towards the collision between England and Spain. In 1586 Walsingham and his agents unravelled a Catholic plot against Elizabeth’s life, and it implicated the Queen of Scots. Mary paid for it with her life in February 1587 at the block in Fotheringay Castle. Her death eased Protestant fears about the succession, because it left as the most likely heir to Elizabeth Mary’s son, James, who had been raised apart from his mother as a Calvinist. Yet for all that it brought the Armada closer. While Mary had been alive Philip had sometimes doubted the wisdom of overthrowing Elizabeth, heretic though she was. The restoration of Catholicism would have put Mary on the throne, with all her ties of blood to the French, and strengthened the bonds between England and France. Philip had not wanted that. But now such fears had fallen from the block with Mary’s head. Indeed, Philip himself stood forward as the legitimate Catholic heir to Elizabeth’s crown, claiming the legacy bequeathed him by his former wife, Mary, the last Catholic Tudor. His Armada would restore a rightful religion, and a rightful king.

None saw that coming Armada more clearly than Francis Drake. Few were so reluctant to see it as Elizabeth. How different they were, the aggressive, fiery zealot and the cautious, war-weary monarch. For Drake life was approaching its climax, the ultimate contest for which he had been preparing all these years – a decisive clash of armour not just between England and Spain but also between God and Antichrist. Far from shrinking from it, he thirsted for the action, supremely self-confident, guided by temperament as well as logic to the opinion that Elizabeth must strike first, disorient her enemies and disrupt their preparations. No sooner was he home than he was canvassing for another expedition.1

Elizabeth listened to Drake because she recognized his unswerving loyalty and understood his value, and perhaps because she often found his hearty and frank conversation entertaining. But every time she saw the burly little seaman swaggering forward she knew what he was going to say. He wanted money, ships and men to hit Philip hard. Strike Spain now, before the Armada could sail! His message was always the same, and there were always those, like Walsingham and Leicester, who would echo it.

And yet she feared to let them have their way. She could not comprehend the depth of their hostility to Spain and the Pope, and she took a broader view of the international scene. To her it was not purely a matter of Spain and England. She could not forget that France was her closest neighbour and had long been her rival. How would it serve England to destroy Spain, the one country capable of curbing the power of France? Not only that but a war, any war, would fracture her hard-won and fragile solvency. She had only to review the annals of her father’s reign to learn how money squandered on foreign adventures could beggar the Exchequer. Despite the legacy of her extravagant forbears she had paid her debts, revalued the debased coinage and created a reserve fund, but with a gross income of less than half a million pounds a year her government was already in trouble again. Everybody wanted money. Drake wanted it for ships. Leicester wanted it for his Netherlands army, although it had performed little and had exceeded its allocated budget of £126,000 a year. The Dutch wanted money, and so did the French Huguenots. With chagrin Elizabeth saw her chested reserve fall by four-fifths between 1584 and 1588 to a mere £55,000, less than it would take for the full mobilization of her fleet. She had looked for dividends from Drake, but however successful his raid of the West Indies had been militarily it had failed her financially. There was an alternative, one she should have taken, but she hated to use it. She could ask Parliament to raise taxes. Elizabeth’s perennial stringency reflected less a lack of wealth than a reluctance to tap it. The propertied escaped lightly under her regime. Her take from the national income may have been as low as three per cent and custom rates remained low. This was one reason why so many merchants were able to sink funds into privateering. The queen’s reluctance to tax more heavily was, in the light of growing national danger, probably irresponsible but not unreasoned. Taxation caused unrest, and it increased Elizabeth’s dependence upon Parliament, which alone had the right to grant it. She resisted putting herself in the hands of those whose judgement she distrusted. And she resisted a more oppressive taxation. So she prevaricated and stalled while the storm brewed about her, grasping the flimsiest straws to preserve peace, clinging to hope after it had gone. Drake and Elizabeth were bound by a common patriotism, but they exasperated each other whenever they discussed policy.

In the autumn of 1586 Drake was bothering her with a new plan to assist Dom Antonio, who as usual had been talking about the thousands of followers who were going to flock to his standard the moment he set foot in Portugal. Replying in kind, Elizabeth fobbed the pretender off with another familiar line: she would act if he could find someone to share the burden. Consequently, that October Sir Francis Drake found himself bound for Rotterdam and Middleburg with eight ships, carrying troops and money for Leicester and a brief to curry support for Dom Antonio from the Dutch. He was only partly successful. Officially, the Dutch would not commit themselves, but they gave out that private shipowners were free to co-operate with Drake if they wished, and it was said that Holland and Zeeland eventually offered to place thirty or forty armed transports at his disposal. The visit also enabled Drake to exchange news and gossip with Leicester – the earl’s man, Robert Otheman, once found the two seated at chess – and then to bring him home with a handful of Dutch deputies in November. Drake called upon Dom Antonio at Eton to acquaint him with the result of his mission, and in December was lobbying the Privy Council for leave to fit out ships. Apparently he had some success, too, for soon Spanish agents had letters flitting across the Channel with news that disturbed Philip greatly: Drake was preparing for sea again.2

Drake was seldom happy with precise planning. Like every great opportunist he preferred a flexible schedule that he could tailor to circumstance, and his ideas about the voyage shifted considerably over the winter and spring. By February 1587 he had dropped the Dom Antonio scheme in favour of a replay of his West Indian raid, involving attacks upon the Main between the island of Trinidad and Puerto de Caballas in Honduras, and a strike at San Juan d’Ulua at a time when the ships of the Mexican flota would be beached there.3 Whenever Drake started talking about treasure, mouths began to water, but on this occasion national security demanded his presence at home. There was no question of England’s greatest seaman crossing the Atlantic when provisions and ships were converging on Lisbon for the invasion of the realm. The West Indian proposal, if it was ever more than a tentative suggestion, was short-lived, and in its place was advanced a pre-emptive strike against Philip’s Armada.

On 15 March, 1587 Drake’s new commission was signed, and it was entirely to his satisfaction. Strategic purposes dominated this new adventure. He was instructed to impede the flow of ships and supplies from Andalucia and Italy to Lisbon, to distress the enemy fleets within their own havens if possible, and – here was the sop to private enterprise – to intercept heavily laden homeward-bound ships from the West and East Indies. If Drake discovered that the Armada had sailed before he reached Spain, he was to confront it and ‘cut off as many of them as he could, and impeach their landing’ in England.

Once again it was a joint-stock operation. The principal investor was the queen, who supplied the Elizabeth Bonaventure (Drake’s flagship), the Golden Lion, which served as vice-admiral under William Borough, the Dreadnought under Rear-Admiral Thomas Fenner, and Henry Bellingham’s Rainbow, as well as two pinnaces. Next came the London merchants, with whom Drake signed a contract on 18 March. They provided about a dozen ships and pinnaces, including some substantial vessels such as the Merchant Royal, Susan and Edward Bonaventure. The names of the merchant investors survive: Thomas Cordell, a wealthy mercer, member of the Levant Company, and formerly engaged in the Spanish trade; the Banning brothers, Paul and Andrew, grocers who had turned to privateering after the collapse of their trade with Spain, and who also had interests in the Levant Company; Edward Holmeden, a grocer trading with the Levant; John Watts, clothier, another fugitive from the Spanish trade; and Richard Barrett, Hugh Lee, William Garraway, Robert Sadler, John Stokes, Robert Flick, Simon Borman and others who, whether grocers, haberdashers, fishmongers or drapers, were men of substance all. The balance of the fleet was provided by Drake and Howard of Effingham, the Lord Admiral. Drake’s four ships commemorated his family, and included the Drake, the Thomas Drake and the Elizabeth Drake, and Howard supplied the White Lion. As an indication of the relative contributions, as determined to apportion prize money, it was reckoned that the queen provided 2,100 tons and 1,020 men; the merchants 2,100 tons and 894 men; Drake 600 tons and 619 men; and Howard 175 tons and 415 men.4

After signing the contract with the merchants, Drake left with his wife for Dover to take ship for Plymouth, where the expedition was to be assembled. It was the largest he had commanded, and after Thomas Fenner led in the London contingent at the end of March it numbered twenty-four ships and about 3,000 men. According to Fenner, Drake

with all care doth hasten the service, and sticketh not to any charge to further the same … The General spareth not in great charge to divers men of valour, as also layeth out great sums of money to soldiers and mariners to stir up their minds and satisfy their wants in good sort. There is good order and care taken for preservation of victual, and men very well satisfied therewith, the General encouraging them.5

Notwithstanding his efforts, Drake still fretted. There had long been a paranoid element in his character, a darkness instilled into him by Doughty, Knollys and the world of plot and counterplot that formed such an important part of the Elizabethan political scene. This time he noted the unusual number of men who defected from his forces while they were waiting in port, and suspected that it was due to the machinations of his enemies. He was reassured, however, by his officers. ‘I thank God,’ he wrote to Walsingham, ‘I find no man but as all members of one body to stand for our gracious Queen and country against Antichrist and his members.’ To all appearances Borough, Fenner and Bellingham were ‘very discreet, honest and most sufficient.’6 The other matter troubling Drake was the queen’s notorious habit of altering her mind. Pinning Elizabeth down was like nailing jelly to a wall. He had prepared expeditions to see her abort them, and had had to scurry from Plymouth leaving his provisions ashore rather than risk awaiting her recall. So it was now, for even as Drake was sailing the queen had further thoughts about those instructions. As if the Armada were an illusion, and Philip’s intentions were not thoroughly transparent, she decided she must not unnecessarily provoke him. New orders were sent to Plymouth, forbidding Drake from entering Spanish ports or threatening their property ashore; he must confine himself to seizures at sea. But it was too late, for Drake had foreseen the change of heart.

His ships were already at sea. On 2 April from his cabin on the Elizabeth Bonaventure he wrote a farewell to Walsingham that expressed the sense of urgency on the eve of this, his most brilliant adventure:

The wind commands me away. Our ship is under sail. God grant we may live in His fear as the enemy may have cause to say that God doth fight for Her Majesty as well abroad as at home … Let me beseech your honour to pray unto God for us that He will direct us the right way … Haste!

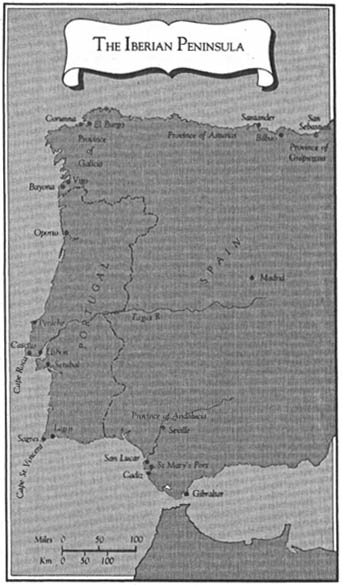

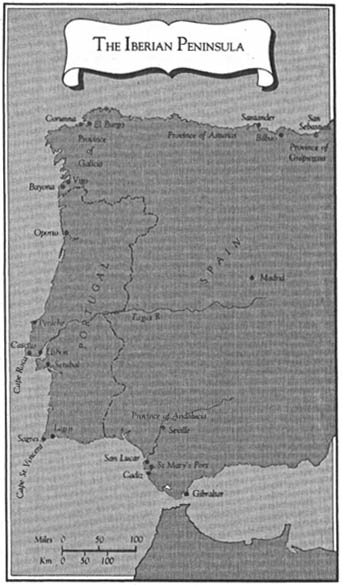

Wasting no more time than to commandeer two privateers, seize a few prizes and round up his fleet after it had been hammered by a week long storm, Drake bowled to the Spanish coast with the intention of taking it by surprise.7 He moved so quickly that when he arrived off Cadiz on 19 April much of his fleet was trailing behind. Drake would not wait for them. He did not even wait to reconnoitre the port and its defences. It was crowded with shipping and provisions for the Armada; the wind was fair for an attack, and after a perfunctory council in which the vice-admiral counselled caution, Drake bore down on his enemies like one possessed.

William Borough was horrified at Drake’s action. A brilliant navigator, whose reputation rested solidly on his charts of the White Sea and work on the variation of the compass, Borough was nevertheless a plodding, conservative and quarrelsome naval commander who had stood out against the revolution in warship design that Winter and Hawkins were bringing about. Now the rash attack of Drake’s was too much for him. There were, indeed, grounds for apprehension. Cadiz had two anchorages formed by an offshore island at the south-eastern end of the bay, but the only entrance was dominated by several batteries – at the point, in the castle and by the harbour – and beset by difficult shoalwater, while the passage between the outer and inner havens was only a half-mile across and could easily be secured by the positioning of guns at the narrows. However, as usual Drake was a step ahead. The port was unsuspecting, the batteries weak, and most of the sixty ships and many smaller vessels inside the harbour were unarmed. Some were storeships destined for the Armada, and others had provisions for it. Still more were innocent merchantmen caught in a war that was not of their making. Drake had caught them unawares and would not afford them time to seek sanctuary beneath guns, behind shoals or up creeks. Without flying any flags or distinguishing pennants, the English ships were led by the Elizabeth Bonaventure past the batteries and into the outer anchorage.

No one contested them. As an apparent eye-witness admitted, ‘the nonchalance that there was was so great and the confidence that no enemy would dare to enter the bay, as they were so little accustomed to see sea-going ships dare to do so, nor had it been heard in many centuries previous of any having such daring to break through the gates and entrances of their port.’ It was the same old Drake, doing what was not so much difficult as unthinkable. Two Spanish war galleys, long and rakish, were eventually propelled forward by banks of oars to investigate the intruders. Galleys had dominated warfare in the Mediterranean since ancient times, but they were no match for the hardier deep-sea sailing ships Drake had brought, with their stout timbers and superior artillery. As soon as the galley commanders realized that the newcomers were unfriendly, they fled without firing a shot. The queen’s ships now raised their flags and fired after the retreating galleys, putting a ball through one of their midship gangways and killing several of the oarsmen. When some of the other eight galleys that were in the port also bravely advanced, the English scourged them with shot and drove them to shelter.8

Panic now overwhelmed the defenceless shipping in the outer harbour. Some fled for refuge in the adjoining river estuaries of St Mary’s Port and Porto Reale, others were abandoned, and one, a big thirty-or forty-gun Genoese ship estimated at 1,000 tons, made a fight of it. Drake would have liked to capture her, but she was stubborn and fought until she was sent to the bottom of the harbour with a rich cargo of merchandise. On shore the Spaniards thought Drake intended sacking the city, and rushed terrified into the castle, suffocating or trampling to death about twenty-six fellow citizens in the crush. It was some time before the Corregidor, Juan de la Vega, restored order and soldiers reoccupied the town square, set up a guard and covered possible landing places, while the galleys drew up in battle formation at the waterfront. Messages for help fanned out, to Seville, Jerez, San Lucar and elsewhere.

Apprehension was not confined to the Spaniards. William Borough was more impressed with Drake’s vulnerability than the town’s, and that evening called upon the admiral on the Bonaventure, apparently to urge him to withdraw. As he left Drake’s cabin he met Captain Samuel Foxcroft and ruefully told him that he could drum no sense into his superior. In fact, far from quitting, Drake was only getting into his stride. The night was cold and dark, but the English set it aglow as they began removing cargoes from their prizes and putting a light to the empty ships. Then, in the early hours of 20 April, Drake led a flotilla of ships’ boats into the inner harbour, where they found the greatest warship in Cadiz, a 1,500-ton galleon belonging to Santa Cruz himself, the leader of the Armada. She was laden with iron and had no guns mounted, and Drake shortly set her ablaze. Poor Vice-Admiral Borough was in dismay. He again called on the Bonaventure, while Drake was leading this new attack, and unable to find the admiral had himself rowed forward to Robert Flick’s Merchant Royal, which was stationed in an advanced position by the entrance of the inner anchorage. There he learned that Sir Francis was further still, attacking Santa Cruz’s galleon. It seems that Borough then began to take it upon himself to initiate a withdrawal in the admiral’s absence, for he spoke to Captain Flick ‘in fearful sort’ and urged him to retire a little, ‘for he thought it better to be gone than to stay there.’ Flick believed that his vice-admiral was afraid of the galleys.9

When Drake returned from his incursion into the upper anchorage he met Borough. There are fundamental disagreements about what happened next, but the most likely explanation is as follows. The batteries in the castle and the town and the galleys had been ineffective, but on the 20th the Spaniards established another battery on a commanding height and it opened fire upon Borough’s ship, the Golden Lion, sending a shot through her timbers below the waterline and breaking the leg of a gunner on board. According to Drake, Borough then came to him trembling with fear and whining about the possibility of one of the queen’s ships being dismasted. This is probably exaggerated, but certainly the vice-admiral returned to his vessel and without orders from Drake withdrew about two miles from the rest of the fleet, off St Mary’s Port. More remarkably he tried to persuade others to join him, using his authority to instruct Captain Bellingham to follow suit. Captain Henry Spindelow, who was aboard Bellingham’s Rainbow that morning and saw her captain returning from Borough’s ship, said that Bellingham told his master to weigh with the Golden Lion if Borough stood further out. Spindelow could not resist the sarcastic remark that in his opinion the vice-admiral was far enough from the action already.10

Nevertheless, Drake could not let Borough stand alone off St Mary’s Port, and authorized six ships, including the Rainbow, to support him. It was true, as Borough later pleaded in extenuation, that so positioned he could secure Drake’s rear from the galleys, if indeed it needed protection, but he also forced the admiral to weaken his force deeper inside the harbour. Fortunately, the Spaniards could do little to arrest his progress. During the night of the 19th and throughout the 20th some 6,000 men had arrived in Cadiz in response to the calls for help, and the Duke of Medina Sidonia came from San Lucar to take command, but they could only watch flames enveloping Drake’s remaining captures. ‘With the pitch and tar they had, smoke and flames rose up, so that it seemed like a huge volcano, or something out of Hell … A sad and dreadful sight,’ said one.11 How many ships were destroyed or captured is in dispute. Drake claimed thirty-nine: two galleys sunk, along with the Genoese ship; Santa Cruz’s galleon and thirty-one other vessels of between 200 and 1,000 tons burned; and four prizes brought away. Fenner spoke of thirty-eight sunk or brought away, including fourteen or fifteen Dutch ships, five Biscayans, Santa Cruz’s galleon, a shallop, three flyboats and about ten barks. Spanish sources suggest serious but slighter losses, of which the lowest estimate appears to be twenty-five ships, worth 172,000 ducats.12

When his work was done Drake prepared to leave, but at the critical moment the wind fell and left his ships becalmed, and it was not until early the following morning, while it was still dark, that he led them out, ‘as well as the most experienced local pilot,’ marvelled a Spaniard. In the bay the wind deserted the English again, and the galleys took advantage of it by attempting a sortie against them, but they were quite unequal to the task. The superiority of the armed sailing ship over the galley had been demonstrated in earlier naval operations, but never more effectively or definitively than at Cadiz.

Drake’s destruction of the shipping in Cadiz, his ‘singeing of the King of Spain’s beard’, as he put it, rightly stirred Europe. Not even Philip’s own cities and fleets were free from humiliation at the hands of this arrogant Englishman. The impudence, dash and damage of the raid even raised doubts as to whether Spain, albeit the greatest power on earth, could handle England besides her many other commitments. Reflecting inaccurately upon the subject the Pope exploded in admiration for his foes:

The King goes trifling with this armada of his, but the Queen acts in earnest. Were she only a Catholic, she would be our best beloved, for she is of great worth! Just look at Drakel Who is he? What forces has he? And yet he burned twenty-five of the King’s ships at Gibraltar, and as many again at Lisbon. He has robbed the flotilla and sacked San Domingo. His reputation is so great that his countrymen flock to him to share his booty. We are sorry to say it, but we have a poor opinion of this Spanish Armada, and fear some disaster.13

Exhilarated as Drake himself felt about the victory, he knew it was merely a good beginning. He had destroyed ships and provisions at Cadiz that had been destined for the Armada, and he had inflicted tremendous psychological damage, but there were other contingents, at Passages and Lisbon, and in the Mediterranean at Gibraltar, Cartegena and Italy. And everywhere he saw evidence of Philip’s determination to invade England. As he made his way to Cape St Vincent to disrupt the co-ordination of these movements, he wrote home to Walsingham, warning him of the danger and begging him to force the queen to a strong stand. ‘I dare not almost write unto your honour of the great forces we hear the King of Spain hath out in the Straits,’ he wrote. ‘Prepare in England strongly, and most by sea. Stop him now, and stop him ever!’14

Cape St Vincent, a promontory more than 100 miles south of Lisbon, was Drake’s next destination. By stationing his fleet off this strategic headland he could intercept shipping bound for Portugal from Andalucia and the Mediterranean and disrupt communications. First, he needed a base from which to sustain the vigil, a safe anchorage for his ships, and a place where the men could land to refresh and reprovision themselves, and he decided to seize the Cape itself. It was an idea that brought Vice-Admiral Borough to boiling point.

Borough, it is true, was an irritable, conservative man, but no more than Doughty and Knollys was he entirely to blame for the difficulties that were developing with Drake. Part of it lay in Drake’s arbitrary and sudden decision-making, his habit of listening to others only to ignore their counsel, and his rapid changes in direction as circumstances altered. Ultimately, he depended upon his own judgement and initiative and needed no reinforcement. Nor did Sir Francis fully understand how to nurture proud subordinates who were his social or professional peers. While he was able to inspire devotion among many officers, like Fenner and Crosse, he lacked the ability to make all men feel they mattered, the skill in teamwork that later distinguished Nelson. Any resentment Doughty and Knollys bore a commander of inferior social status had been sharpened by the disregard he too frequently showed for their opinions. Borough was no high-born gentleman. He was not of the stamp of Knollys or Doughty, but he was older than Drake and more than a thoroughly professional seaman. He had participated in the early voyages to the north-east and deserved his reputation as one of the pioneers of Elizabethan overseas endeavour. Yet his counsel had been ignored outside Cadiz; he had not been informed of the foray into the inner harbour there; and now the first he heard of the plan to seize St Vincent was when he came aboard the flagship on 29 April and heard some common soldiers speaking about it by the helm. They knew more than the vice-admiral of the fleet!

Borough was upset, and rightly so, but he acted unwisely nonetheless. Returning to the Golden Lion, he addressed a long letter of complaint to the admiral, protesting that the officers were mere ‘witnesses to the words you have delivered’, entertained perhaps by Drake’s ‘good cheer’, but nevertheless dismissed from meetings ‘as wise as we came’. The admiral was ‘always so wedded to your own opinion’ that he regarded criticism as offensive. As for this attempt upon St Vincent, that was far too bold a stroke for Borough, and he bombarded Sir Francis with objections: there was neither a suitable landing nor watering place at the Cape; Drake’s instructions prohibited him from setting foot on Spain’s territory; there was no advantage to be gained, except as bravado; the place was impregnable; the coast was already alert and ready for the English; and galleys from Cadiz or Gibraltar might Separate landing parties from the ships by using the shallows, or even attack the fleet if it became becalmed. On and on he went.15

We can imagine Drake’s contempt upon reading such a letter as this. It bore testimony to the gulf between the two men, for had Drake been a Borough he could never have been a Drake. The admiral saw the weaknesses as well as the strengths of his enemies, and profited by them. He was hardly a man to quake at the prospect of assaulting the remote strongholds on a Cape now central to his purposes or of meeting galleys he had already discredited at Cadiz. And as for instructions, he had always exceeded them, and sometimes knew that the queen and Walsingham expected him to do so. Borough enjoined Drake ‘to take this in good part’, but hardly knew the man before him. Nothing provoked the admiral more than insubordination. Nothing stirred those dark suspicions that always lingered in his head faster. Drake now minded how Borough had hung back at Cadiz, advised him to delay the attack, and retired prematurely from the hottest action. Bottling his fury for the moment, he handed the letter to his chaplain, Philip Nichols, and to Fenner for their opinion. They decided that it was prating in tone and that it charged Drake with inefficiency (‘You also neglected giving instructions to the fleet in time and sort as they ought to have had, and as it ought to be,’ Borough had written). Although Borough rushed an apology to the admiral as soon as he learned of the offence his letter had caused, it was too late. Drake deprived him of his command and confined him to cabin, naming the sergeant-major of the soldiers, John Marchant, as the new commander of the Golden Lion. It was a sad day for a seaman of thirty-five years’ standing, a middle-aged man whose accomplishments had made him the comptroller of the queen’s navy.

Having disposed of the unhappy Borough, Drake returned to his search for a base. He made a stab at Lagos, east of St Vincent, but found it too strong, and then struck at the four forts at Sagres and Cape St Vincent. This time he led the attack in person. On 5 May about eight hundred arquebusiers and pikemen were disembarked on the beach of the Bay of Belixe and wound their way up the cliffs towards the fort of Valliera. It was defended by six brass pieces, but the garrison withdrew immediately to Sagres Castle to the south-east, the strongest of the forts. Sagres Castle occupied about 100 acres of ground and was a position of some strength. Its garrison was small, only about 110 Portuguese soldiers, but its location was formidable. It was perched defiantly upon the summit of towering cliffs, which fell from its walls on three sides and made it approachable only from the north by a path some 180 paces across. The castle walls themselves, judged to be around 10 feet thick, rose another 30 or 40 feet, and the one across its front zig-zagged so that no part of it could not be covered by the arquebusiers and bowmen on the battlements. Eight pieces of artillery enfiladed the approaches.

Drake had his men exchange shots with the garrison at Sagres and then summoned it to surrender. When the Portuguese refused he sent to his ships for wood. Eventually all was ready, and the admiral detailed his arquebusiers to pin down the defenders while he led the advance upon the great wooden gate, piled the faggots against it and set it alight. Briefly the garrison resisted, killing and wounding a few of Drake’s assault party, but perceiving the determination of the English and, according to one report, running short of ammunition, they called for a parley. Drake let them depart with their baggage and then occupied the castle, and the following day turned his attention to the two remaining forts, one a fortified monastery and the other another castle. Neither offered resistance, although one commanded seven brass pieces and the castle, like Sagres, could only be reached along a single path.

Drake now controlled the bays on both sides of Sagres headland, and his men spent two days gutting the monastery and forts and a nearby village, and pitching the captured guns over the cliffs for collection by the sailors on the beach. Once again, the symbols of the hated Catholicism received special attention. A Spanish account recorded that

the nefarious English entered the holy convent [of the monastery]; they carried out their customary banquets and drunken revelry, their diabolic extravagances and obscenities; they stole all they could get their hands on and set fire to the place. Likewise, they carried out a thousand acts of contempt and profanities on the images of the saints, like unadulterated heretics; because, just as darkness is offended by light, so these infernal people abhor radiant brightness.16

Meanwhile, Drake’s ships were already at work, scouring the local bays and destroying every vessel they could find. By Fenner’s count forty-seven caravels and barks laden with hoops, pipe-boards, planks and oars were burned. These were the materials that Santa Cruz needed to make casks to store provisions for the fleet, and when the Armada eventually sailed the following year the rot that prematurely afflicted its supplies was in no small way due to the Spaniards’ having to use unseasoned wood for casks after Drake’s raid destroyed so much of their supply of seasoned timber. In addition, Fenner reckoned that between fifty and sixty fishing boats with their nets were also destroyed. Drake took little satisfaction from this ruin of the local tuna fisheries, and tried to explain to the bereft Portuguese mariners that he could not help the exigencies of war. But he also knew that he was reducing the food supplies available to the Armada.

During these operations Drake had the effrontery to appear off Lisbon, where Santa Cruz’s fleet was assembling, and blockade the port for two days, driving vessels ashore and capturing a caravel. He dared the old admiral to come out and fight. Santa Cruz was no milksop. He had made the transition from galley to sailing-ship warfare, having fought against the Turks at Lepanto and defeated Strozzi off the Azores. How ever, the guns had not been mounted on his ships and he had few men for them, while the galleys at his disposal were no contest for the queen’s ships. The old Spaniard could only fume in humiliation. Truly the Venetian ambassador in Madrid wrote, ‘The English are masters of the sea, and hold it at their discretion. Lisbon and the whole coast is, as it were, blockaded.’17

While Drake held the coast the ships and supplies that had been converging on Lisbon were paralysed. Ten war galleys that met him near Lagos only escaped by retreating behind rocks and shoals. Soldiers being shipped from the Mediterranean to join Santa Cruz dared proceed no further than Cadiz, where they were put ashore and told to continue their journey overland. Much of the local carrying trade was suspended. It seemed as if Drake might rampage at will for months, starving Santa Cruz of reinforcements and provisions, and meanwhile in England four of Elizabeth’s ships and twelve merchantmen were being fitted out to join him off Cape St Vincent. Then, suddenly, Drake was gone. It may be that he doubted his ability to maintain the station because his men were sickening, but the most likely explanation of his abrupt departure is that he had heard of rich ships for the taking, somewhere near the Azores, and meant to have a share of them.

Some historians have been strongly critical of Drake’s voyage to the Azores, and cited it as an example of his alleged willingness to subordinate the national interest to naked profit-seeking. Going further, some have dismissed Sir Francis as an innate corsair, a predator pure and simple, for whom plunder was the principal objective. While none would deny that Drake was always interested in money, at sea or ashore, these criticisms have been taken too far. Drake’s letters reveal that religion, even more than gold, dominated his mind, and for Drake the causes of God and England were one. It is difficult to believe that this fiery, almost fanatical zealot would have betrayed them.

It must also be remembered that the navy of Elizabeth I was not financed like that of today. The Crown provided less than half of the funds that created Drake’s expeditions. All Elizabethan naval commanders were more or less dependent upon private finance, and had to ensure a financial return if they wanted similar backing in the future. Even the queen’s investment was often made with a view to profit. The men who led her fleets were generally corsairs as well as admirals. Plunder, whether it detracted from strategic aims or not, was inextricably built into the system. If it was a failing, it was an institutional rather than purely a personal one. Sir Francis Drake could not operate outside this context. He had to respond to his paymasters, and as those paymasters were primarily private investors looking for gain he must necessarily seek the means to satisfy them. When Drake sailed for the Azores in 1587, far from neglecting his duty, he was doing it. To condemn him as a mere mercenary on these grounds is to condemn him for the circumstances that controlled him, and indeed for being an Elizabethan.

That Drake remained a corsair does not preclude him from also having been an admiral. To some extent these same conditions had influenced naval operations throughout the century. Even the Duke of Albuquerque, who secured for Portugal control of the Indian Ocean, and whom many regard as the finest naval strategist of the day, launched plunder raids to compensate for the shortcomings of the funds sent by his sovereign. In 1514 he abandoned an expedition to Aden and the Red Sea to attack Ormuz, the wealthy entrepôt at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, for precisely that purpose. Yet no historian has dismissed Albuquerque as a mere corsair. Although Drake rose from the ranks of the corsairs, and plunder remained a strong imperative in his career, no more does the term justly account for the complexity of his motivation and the range of his operations.

An ugly incident marked the beginning of Drake’s dash for the Azores, and the Golden Lion, now commanded by Marchant but with Borough still aboard, was at the heart of it. The crew of the ship were in poor shape, debilitated by the blockade and reduced victuals, and when a storm dispersed the fleet it seems to have been the last straw. They demanded that Captain Marchant take them home, and when he refused put him in a pinnace so that he could return to the admiral. The Golden Lion herself made for England, and Borough went with her. His part in the mutiny is unclear. He had been deprived of his command, but had addressed the men, telling them that their best course was to lay their grievances before Drake. How earnestly he tried to return the company to its duty, and how far he feared for his life if he protested too loudly, is uncertain, but the admiral’s reaction to the news of the defection of the Golden Lion was predictable. Without hearing any important evidence, he convinced himself that Borough had not merely done insufficient to stop the mutiny, but was part of it, and empanelling a jury, he had a verdict returned and the death sentence pronounced upon Borough and some of his officers. Not one of the men charged was present to answer the allegations.

The storm and the flight of the Golden Lion left Drake with only nine ships, but he led them to the Azores and raised the island of São Miguel on 8 June. Towards dark a large sail was spotted beneath the land, and it was surmised that she was a man-of-war. Early the following morning a ship was seen again, probably the same one, and Drake steered for it. Shortly the improving light revealed a great red cross emblazoned on the ship’s sail, and the English realized that they had stumbled upon one of the fabled East Indiamen that shipped the riches of the Indian Ocean to Europe. In fact this Portuguese carrack, the San Felipe, was even more than that. She was the king’s own ship, reputedly among the greatest in the East India fleet, and carried a double cargo, for she had taken aboard the goods of the San Lorenzo, which had sprung a leak and foregone the voyage. It was said she had twenty-two brass guns, many iron ones, and 659 passengers.

This was a magnificent prize, certainly, the greatest taken by the English since Drake’s capture of the Pacific treasure ship eight years before, but no easy conquest, for the San Felipe’s tonnage exceeded that of the three largest English vessels combined. The admiral closed upon her without distinguishing colours, and when he was within range suddenly raised flags, pennants and streamers to declare his identity, and called upon the carrack to yield. There was an exchange of gunfire in which the smaller English ships slunk beneath the great Indiaman’s shot to cling on her flanks and bow like mastiffs worrying a baited bull, firing into her hull as she lurched about, trying to defend herself with her guns and the incendiaries that she probably projected from mortars or periers. Surrounded, and with six men killed and others wounded, the San Felipe was forced to surrender.

When the English came aboard her they were astonished at the wealth they found – great quantities of pepper, calico, cinammon, cloves, ebony, silk, saltpetre, jewels, reals of plate, china, indigo, nutmeg, gold and silver – everything that had made the East fabulous. Drake sent her crew, including the black slaves, away in one of his ships, and started for home with his prize, there being no further question of returning to Cape St Vincent with such a reduced force. The capture of the San Felipe had ‘made’ the 1587 voyage. The attack at Cadiz and Drake’s brilliant work off St Vincent may have disrupted Spanish preparations for the Armada, but in the eyes of most English contemporaries the dazzling fortune brought home in the carrack was the perfect consummation of the adventure. It stimulated anew the desire to reach the East, and it was Drake’s backers who were to become leading lights in the formation of the East India Company at the turn of the century, Paul Banning, William Garraway and Thomas Cordell becoming directors and John Watts its governor.

But the diversion to the Azores was not only a commercial success, for it, rather than the operations off the Spanish coast, postponed the sailing of the Armada for a year. Remarkable as Drake’s offensive had been, the naval campaign had only frustrated Santa Cruz temporarily. It was the sudden departure of Drake from the coast and the fears it raised in Spain for the safety of the opulent ships coming home from the East and West Indies that did the long-term damage. To protect them Santa Cruz was bullied into scraping a fleet together and putting to sea in June in search of the English, but by the time he did so Drake had gone. The Spanish admiral cruised uselessly to the Azores and back, returning in October, his ships in disrepair, his men sick and his stores depleted. Philip had planned to launch the Armada against England in 1587, but the debilitation of Santa Cruz’s fleet during the Azores voyage made it impossible. It would have to be postponed until 1588, and Elizabeth had gained a valuable year in which to prepare for it. Drake had proved that this time at least commercial profit and national security were not incompatible.

Drake arrived in Plymouth on 26 June, dispatched Fenner to the court with a preliminary report, and shortly followed with a casket from the San Felipe as a present for the queen. The mere beginning of a long inventory of its contents suggests the wealth Drake had brought home:

Six forks of gold; twelve hafts of gold for knives, to say, six of one sort and six of another; one chain of gold with long links and hooks; one chain of gold with a tablet having a picture of Christ in gold; one chain with a tablet of crystal and a cross of gold; one chain of gold of esses, with four diamonds and four rubies set in a tablet; one chain of small beadstones of gold … 18

It was said that Elizabeth was displeased that Drake had committed such open acts of war as the seizure of forts and the entry into Cadiz, and her notorious reluctance to goad Philip too far as well as her attempt to amend Drake’s instructions before sailing indicate that this was so. At least, it was diplomatic to affect to be annoyed. Yet Drake’s fleet had done her great service, buying her time and providing some of the money she desperately needed. She did well out of the sale of the great carrack. Commissioners to assess its value, including Sir John Gilbert and John Hawkins, were appointed on 1 July, and eventually they reckoned the cargo, exclusive of ship and guns, to be worth a staggering £112,000. It took seventeen ships to carry it from Plymouth to London and more than a year to realize the proceeds, but in December 1588 the queen was apportioned £50,000 and Drake himself must have netted around £20,000.19

Amidst discharging his men and shipping the cargo of the carrack to London, Drake still found time to pursue the mutineers of the Golden Lion, who had reached England in June. Sir Francis did not accuse the whole of the ship’s company of desertion, and even sought £350 for the wages of those whom he believed had been against it, but he had no comfort for Borough. The month after Drake’s return, he provided charges against the former vice-admiral ranging from maintaining a poor state of discipline on his ship and over-caution (‘if Sir Francis Drake would have been advised by Mr Borough, there had been no service done’) to outright cowardice (‘Mr Borough was so afraid of the shot as he could not tell where to ride with the ship’), and thirty officers, including ten captains, swore to the truth of the allegations. The matter had to be taken seriously, and the Privy Council appointed Sir Amyas Paulet and Mr Secretary John Wolley to consider the charges. Drake himself attended an early session of the hearings at Burghley’s house Theobalds on 25 July.

The affair did credit to neither of the contending parties. Drake had misinterpreted Borough’s original letter of complaint and allowed his emotions to get the better of his judgement, thinking no more clearly than in his ridiculous trial of the offender in absentia after the desertion of the Golden Lion. There were no sufficient grounds for convicting Borough of mutiny, but while he survived the inquiry he had clearly blotted his record. He had retired from an advanced position at Cadiz and counselled against the attack on St Vincent, thus setting himself apart from the great achievements of the voyage, and he had come home with a crew of mutineers, by implication either a deserter himself or incapable of controlling the men he had once commanded. Poor Borough. When the Armada finally reached England in 1588 there was no place in Drake’s fleet for this fine old seaman. Instead he captained Elizabeth’s solitary galley and pottered futilely about the Thames.

Drake never forgave Borough, and was disappointed that he had escaped so lightly, but there were graver matters at hand. After his voyage of 1587 attitudes hardened in both England and Spain. The Venetian ambassador wrote from Madrid that ‘all Spain is in earnest’ and united in a determination to expunge the humiliations Drake had dealt, ‘for they declare that the Queen of England and Drake are obscuring the grandeur of this Crown and the valour of the Spanish nation.’20 Philip’s crusade was now not merely a matter of religion and empire, but necessary for the redemption of national honour.

1 The state papers contain several estimates for fitting out a fleet in September 1586, and one indicates that Drake may have been earmarked for command, although it appears it should have referred to William Winter. State Papers, Domestic, Public Record Office, S.P. 12/193: 26, 29, 35, 42, 49.

2 Motley, History of the United Netherlands, 2: 98, 137.

3 Statement of a voyage projected by Drake and Hawkins, enclosed with Mendoza to Philip, 18 February, 1587, Hume, ed., Calendar of Letters and State Papers … in the Archives of Simancas, 4: 20–3.

4 Statement by William Stallenge, 24 October, 1587, State Papers, Domestic, S.P. 12/204: 46; suretles provided by Drake’s partners, 31 October, 1587, Ibid, S.P. 12/204: 52.

5 Fenner to Walsingham, 1 April, 1587, Corbett, ed., Papers Relating to the Navy During the Spanish War, 97–100. The English documents for this voyage are given in this volume and in Hopper, ed., ‘Sir Francis Drake’s Memorable Service … Written by Robert Leng’. The ‘Brief Relation’ given by Hakluyt is largely cobbled from dispatches and is not in itself a primary source.

6 Drake to Walsingham, 2 April, 1587, Corbett, 102–4. Drake’s accounts for the voyage refer to the apprehension and Imprisonment of men, possibly for desertion (State Papers, Domestic, S.P. 12/204: 27–9).

7 Dasent, ed., Acts of the Privy Council of England, 19: 455–6.

8 Two Spanish relations of the attack on Cadiz are given in Maura, El Designio de Felipe II, ch. 10. One is an eye-witness narrative, and the other a retrospective version from the archives of the dukes of Medina Sidonia. Both were translated for this biography, and copies of the translations have been deposited in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and the Plymouth Public Library. The quotation is from the account of the anonymous eye-Witness, published in Maura, 185–203.

9 Further articles against Borough, 29 July, 1587, Corbett, 156–64.

10 There are difficulties in accepting alternative versions. Borough’s own claim that he visited Drake to discuss victualling seems unlikely. Some evidence does suggest that the Golden Lion was hit while Borough was absent and that it was the master who decided to warp her further out, but even if this was correct, Borough obviously endorsed the decision when he returned.

11 Anonymous eye-witness, Maura, 185–203.

12 A letter by Thomas Fenner to his cousin appears to be the basis of the uncredited account published by Hopper, as well as of that in Haslop, News out of the Coast of Spain. See also Lippomano to the Doge and Senate, 9 May, 1587, Brown, ed., Calendar of State Papers … in the Archives and Collections of Venice, 273–5; Duro, ed., La Armada Invencible, 1: 334–5.

13 Giovanni Gritti to the Doge and Senate, 20 August, 1588, Brown, 379.

14 Drake to John Foxe, 27 April, 1587, Hopper, 30–1; Drake to Walsingham, 27 April, 1587, Corbett, 107–9.

15 Borough to Drake, 30 April, 1587, Lansdowne MS 52, article 39, British Library.

16 Anonymous eye-witness, Maura, 185–203.

17 Lippomano to Doge and Senate, 21 May, 1587, Brown, 276–7.

18 Inventory, July 1587, Hopper, 52–3. For capture of the San Felipe see also Fugger News-Letters, 2: 138–9.

19 State Papers, Domestic, S.P. 12/204: 37, 39, 40; Hist. MSS Commission, Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Marquis of Salisbury, 3: 281–2; Rodger, ‘A Drake Indenture’.

20 Lippomano to the Doge and Senate, 16 May, 1587, Brown, 275–6.