CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

‘IT WAS IMPOSSIBLE TO COME TO HAND-STROKE WITH THEM’

And in your fighting evermore, think you are Englishmen,

Then every one of you I hope will slay of Spaniards ten,

Or any else whatever they be, that shall disturb your peace

And seek by any kind of mean your quiet to decease.

Henry Roberts, A Most Friendly Farewell, 1585

IT IS ONE of the most enduring stories in British history. Captain Fleming, or some other breathless messenger, found the commanders of the English fleet quietly playing bowls on Plymouth Hoe. His announcement that the Armada was on the coast created a whir of excitement, perhaps even of panic, as the captains began to hustle to their ships. Yet Sir Francis Drake himself was unmoved. ‘There is plenty of time to finish the game and beat the Spaniards too,’ he remarked, and so saying he continued his bowling and restored equanimity among the observers. It is one of the most popular stories in history, but among others comparable to it that tell of Robert the Bruce and the spider, King Alfred’s burning cakes and George Washington and the cherry tree, it is not true. There is no credible authority for it.

It was not until 1624 that a shred of evidence for it appeared, and that of the most unimpressive kind. A pamphlet called Vox Populi, printed in Goricum, quoted the alleged words of the Duke of Braganza to the Spanish Cortes, a boast to the effect that the Armada had approached England ‘so cunningly and secretly’ that when it reached the coast ‘their commanders and captains were at bowls upon the Hoe of Plymouth; and had my lord Alonso Guzman, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, had but the resolution … he might have surprised them at anchor.’ Thus the point was not Sir Francis Drake’s unperturbability, but the incompetence of the Spanish admiral. The English admirals were not even mentioned by name. A century had to pass before William Oldys, in a Life of Raleigh (1736), added to the tradition the story that ‘Drake would needs see the game up, but was soon prevailed on to go and play out the rubbers with the Spaniards.’ In Oldys’s version, therefore, Drake was overruled. Tytler, borrowing from Oldys for another book on Ralegh, published in 1832, seems to have suggested the modern wording, for he had Drake insisting ‘that the match be played out, as there was ample time both to win the game and beat the Spaniards’, but the story continued to be embellished and achieved great currency during the Second World War, when England faced invasion once more.1

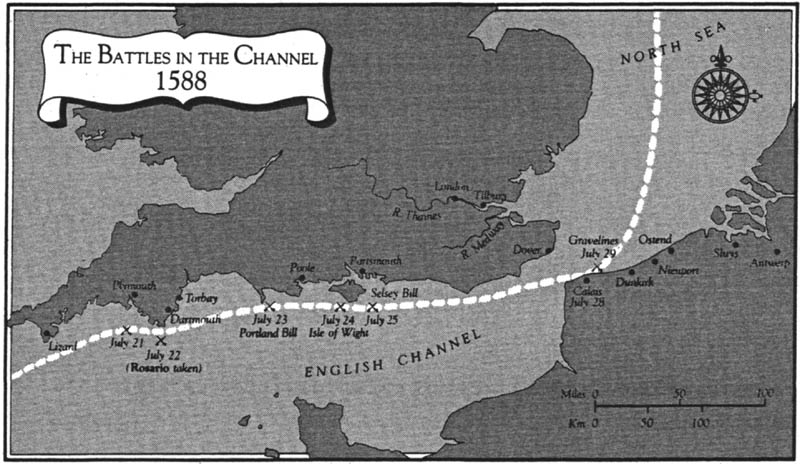

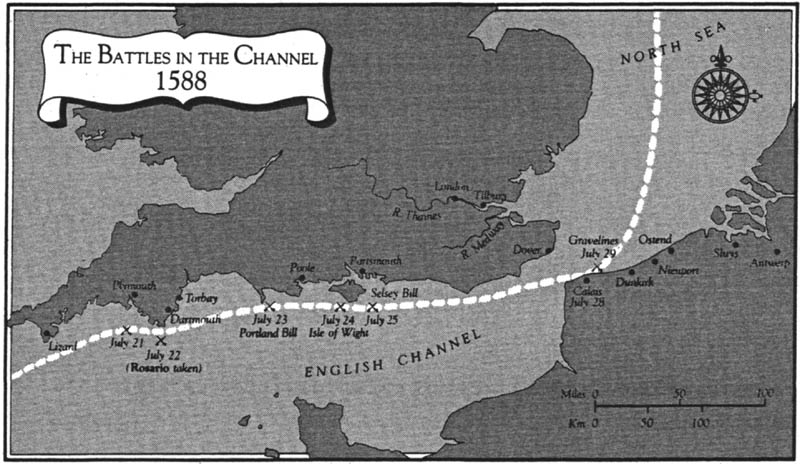

On such flimsy foundations rests the most famous of all yarns about Sir Francis Drake. It was not contemporary, its origin was Spanish rather than English, and its point was that the Armada had caught the English napping, and had Medina Sidonia been formed of sterner stuff he might have destroyed Drake in Plymouth. What really happened that 20 July, 1588, when the Armada lay off the Lizard with the wind at south-west, favouring a Spanish advance towards Plymouth and dead set against the English?

The possibility of an attack upon Drake seems to have come up in a council of war called by the Duke of Medina Sidonia. As far as the Spaniards knew, Sir Francis, the dreaded ‘El Draque’, was in the Sound and Howard still to the east in the narrow seas. Don Alonso Martinez de Leiva, commander of La Rata Santa Maria Encoronada, and named in secret orders as successor to Medina Sidonia, urged an attack upon Plymouth to eliminate part of the English fleet. But Medina Sidonia did not like the idea, and reminded his admirals that such an attack would not only be difficult, for Plymouth was not easy of access, but contrary to Philip’s orders, which cautioned the fleet against unnecessary diversions and fixed it firmly upon the great task of linking with the Duke of Parma. No, it would not do to risk a crippling battle so early in the campaign and so far from the true objective. It was obvious, however, that the Armada might need shelter, from the weather if not from enemy action, and there was no satisfactory port beyond the Isle of Wight. The council of war apparently decided that if necessary the Armada might use the Isle of Wight before making the junction with Parma. In the meantime it would press on – but prepared for battle.

And onwards it came, sighting the English mainland the same day and slipping past the green shores, from which, on headland to headland and hill to hill, the beacon fires could be seen kindling, carrying the word across the realm, faster than the fastest horse. Within hours grim northerners as far as Durham knew that the invaders were here, and the spirit of ’88 was abroad. During those next summer days many men rode along the roads to the coast, not all of them young men, but men enthused with the fervour of Protestant England, men hoping for their chance to fight the Armada. And in the ports little ships were being fitted out. Most of them had never seen battle before, and it was to be doubted if they could be of significant service, even if Howard and Drake wanted them. But they were determined to fight, and to pour from their havens to play their part in the epic and stand a turn in history.

It was a magnificent sight, the great fleet that imperial Spain had sent against England, about 125 ships forming a front of two miles when in battle order, the large fore- and stern-castles on some of the vessels giving them a bulky appearance compared with the smaller English ships that would issue out to meet them. It seemed a more formidable array than it was, with fighting galleons from Spain and Portugal, lumbering Italian galleasses and big armed merchantmen, mixed with numerous freighters and dispatch boats, and massed with 19,000 soldiers armed with arquebuses, muskets and pikes as well as 8,000 sailors. Medina Sidonia’s battle formation resembled nothing so much as the head and horns of a gigantic steer, with the duke’s principal force, including his own 1,000-ton San Martin, some of his warships and the galleasses, composing the head, while on each flank stretched some twenty ships forming the horns, Leiva commanding the left, and the right handled by the Armada’s second-in-command, Recalde, the most experienced admiral in the fleet, flying his flag aboard the San Juan de Portugal. In principle the head was supposed to engage the enemy, allowing the horns to sweep round to encircle them, and drew for inspiration upon the standard Spanish galley tactics of the Mediterranean. Yet for all that the Armada was already displaying some of the weaknesses that would undo it. It was a convoy, shepherding large numbers of transports, and could move only as fast as its slowest member, and its advance was far too ponderous to have caught the English in Plymouth, even if Leiva’s plan had been adopted.

Medina Sidonia did not come close to bottling up Drake and Howard. They must have heard of his approach on the afternoon of 19 July, when the tide was running into the Sound and the wind was at south-west. Getting out would call for seamanship of the highest order. When the tide began to ebb, the English put out boats to tow their ships from harbour against the wind, and it was not until late that night that the movement was under way. Drake had dispatched a messenger, William Page, to speed to the queen with the news, but during the morning of the 20th he was with Howard and fifty-four sail, beating out towards the open sea. In the afternoon they were off the Eddystone rocks when they saw it: an ominous wall of shipping to windward, the Spanish fleet at last. They had seen nothing like it before and Howard could not contain his amazement. All the world, he later said, never saw such a force as this. But there was no time to waste, for the Armada would soon be threatening Plymouth, and as the rain reduced visibility the English spent the remainder of the day and night striving to gain the weather-gauge – the attacking position.

In naval engagements of the sailing ship era opponents might fight from either the windward (or upwind) or the leeward (or downwind) position. Those in the windward position were said to have the weather-gauge. With the wind behind them, they possessed the advantage of being able to attack at their convenience, and to manoeuvre more efficiently, but even if they seriously disabled an enemy vessel by dismasting her they were not always able to make a capture, since an injured ship could generally retreat before the wind to leeward. In the last years of sailing-ship tactics enterprising British admirals attempted to solve the problem by attacking from the windward position, but once engaged passing to leeward to seal off an opponent’s retreat. Dawn of 21 July, 1588 showed that Howard and Drake had got around the Armada to gain the weather-gauge, ready to launch their first assault upon the Spanish rear. How they achieved this position no one knows, whether by working westwards inshore or by striking across Medina Sidonia’s front and passing to his rear around his right flank. Yet it was a considerable feat, only revealed to the Spaniards by daylight. Far from being bottled in Plymouth, or waiting to be attacked from leeward, there was ‘El Draque’ bearing down behind them! If any of the Spaniards had had doubts about English seamanship, they must have shed them that first morning of battle.

Surprisingly, these important naval engagements in the Channel are ill documented from the English point of view. The commanders were evidently too busy fighting to write full dispatches, and the one sustained narrative, given by Howard to Petruccio Ubaldino, is disappointingly scant in its details of Drake. One reason for this is that Howard simply did not know what Drake was doing. In the first two battles, off Plymouth and Portland Bill, the movements of the English ships were somewhat unco-ordinated, with ship’s commanders acting much on their own initiative. The situation proved unsatisfactory, and on 24 July the English endeavoured to obtain greater control by dividing the fleet into four squadrons. Frobisher, in the Triumph, was at the head of one of them, closest inshore; Howard in the Ark Royal had another squadron on Frobisher’s right flank; Hawkins came next; and Drake commanded the seaward wing of the English fleet. Yet even this device gave limited control, for the squadrons operated almost independently, with Drake neither taking orders from Howard nor giving any to Hawkins or Frobisher. In these circumstances the Lord Admiral had no clear idea of what was happening amid the smoke of battle. We find him speaking very satisfactorily of his own exploits, and a little about Frobisher, but he had less to say about Hawkins and nothing of Drake, who for the most part operated independently far to the south, beyond Howard’s cognizance.

There is the possibility, too, that by the time the Lord Admiral was working with Ubaldino he had conceived some jealousy for his vice-admiral. Rumour had it that the public considered that what credit there was in defeating the Armada belonged to Drake, and that Howard resented the idea. Conceivably, the story was without foundation, but it is strange that Howard’s narrative omitted all reference to the engagement of 24 July, when Drake’s division fought a considerable battle with the Armada just off the Isle of Wight and dealt it higher casualties than it had sustained in any previous action. On that day, said Howard, ‘there was little done.’2 That he should draw a veil over an encounter described in many Spanish accounts implies something less than objectivity in his account.

Reconstructing Drake’s movements in the Armada battles is not, therefore, straightforward. Apparently Sir Francis himself recognized the want of information, because when Petruccio Ubaldino – the same concocting an account for Howard – approached Drake for further details, the vice-admiral was happy to redress the deficiency, but his revisions seem to have been interrupted and add little new perspective to the engagements themselves. In consequence it is not to the English, but to the Spanish accounts that historians have looked for the most complete picture of the conflict, and in those Sir Francis and the Revenge emerge more clearly, if still obscurely, from the gunsmoke.3

This was to be a new battle for every one of the participants. It was more than that, for these encounters in the Channel amounted to the first major naval battle that emphasized sails and guns rather than oars and boarders. It marked the beginning of the great age of fighting sail as surely as the ruins of the Turkish fleet at Navarino two and a half centuries later denoted its end. Drake and Howard, Recalde and Medina Sidonia, professional and amateur, all were in for surprises in these fierce clashes. The first belonged to the Spaniards, as they saw the English fleet behind them on the morning of 21 July, south of Plymouth.

The wind, which had been south-westerly, was veering to west-north-west, and Howard and Drake had the Armada to leeward, between Plymouth and themselves. But inshore, still working their way to windward of the Spaniards, were some English stragglers, including a few galleons, and although these eventually passed westwards to join their comrades they formed the initial focus of the battle of Plymouth. The royal standard fluttered to the foremast of Medina Sidonia’s flagship, and the Armada shuffled into battle formation. Hauling in their sheets, the Spaniards steered towards Plymouth, possibly to cut off the English ships that were still to leeward, possibly, as far as Drake and Howard knew, to enter the Sound. The English admirals had little more than fifty of their ships available, but they had to drive the Armada beyond Plymouth, and they plunged after it.

Yet now the English inexperience showed itself. They could not have been skilled gunners, as we have seen, but the little sustained gunnery they remembered had been in unusual circumstances. They had sunk ships by gunfire at San Juan d’Ulua and Cadiz, but then their opponents had been in confined anchorages, unable to manoeuvre from the shot, pinned down beneath a point-blank hammering. In open water it was different, as targets moved in and out of range or in front of or behind other ships, and as the attackers had to pause to go about to bring their guns to bear again. During battles of this kind it was extremely difficult to sink ships by gunfire alone, and even the terrible ship-smashing batteries mounted by Nelson’s ships seldom won victories that way; rather they killed or maimed so many of the enemy’s crew or disabled their ship so badly that it could be successfully boarded or compelled to surrender. Drake and his comrades hardly knew this. They noted those soldiers gathering on the decks of Medina Sidonia’s ships and decided to keep their distance at all costs, apparently believing that their artillery alone could do the job. Instead of moving in close and using their heavier armament to maximum effect, relying upon their superior sailing abilities to get them out of trouble, the English chose to pop away almost harmlessly at a distance. Howard was quite frank about it: ‘we durst not adventure to put in among them, their fleet being so strong.’4

In the first battle off Plymouth it was at once evident that the English ships were too nimble for the plodding Spaniards, but no less so than that the fire of Howard and Drake was having little effect. The weather-gauge conferred an advantage on the English, for as they attacked the Armada’s rear the Spaniards found it difficult to beat back against the wind to support their hindmost consorts. Howard struck at Medina Sidonia’s left flank, firing upon Leiva’s La Rata Santa Maria Encoronada, while Drake led an attack upon the other wing, where Recalde’s San Juan de Portugal, itself more than twice the tonnage of the Revenge, was the leading flagship. Recalde made no attempt to escape, but bravely turned to face the assault, and received the fire of Drake, Hawkins, Frobisher and others for the best part of two hours before some of the heavy Armada ships were able to swing round to rescue him. The English then sheered off and after about four hours the battle of Plymouth came to an end.

Drake had been impressed by Recalde’s courage, and decided to warn Lord Henry Seymour who lay ahead in the narrow seas. As he put it, an exchange had taken place between ‘some of our fleet and some of them’ and ‘as far as we perceive they are determined to sell their lives with blows.’ There were above ‘a hundred sails, many great ships; but truly, I think not half of them men-of-war,’ he added shrewdly. Howard, too, was beginning to gauge the metal of his opponents, and called for more powder and shot, remarking, ‘This service will continue long.’5 The action had been a testing time for both fleets, but while Howard had harried Medina Sidonia beyond Plymouth and demonstrated that his leading warships handled better than the Spaniards, he may have sensed the inadequacy of the English performance. Not a single Armada ship had been taken or destroyed, and Medina Sidonia’s formation had remained basically intact. He did not know it, but even Recalde’s San Juan, which had taken such punishment, had sustained relatively minor damage: torn rigging, a damaged foremast, a cut forestay and a number of dead, fifteen by one account. It seemed as if the English had not only been firing badly, but too high, for little if any injury had been visited upon the hull. Don Pedro de Valdes, admiral of the Andalucian squadron and commander of the Nuestra Señora del Rosario, put it into a nutshell: ‘There was little harm done because the fight was far off.’6

The Armada had successfully repulsed the first attack, and proceeded on through the Channel, edging towards the rendezvous with Parma, but two accidents now cost it the first losses. Recalde wanted to repair his ship in case the English renewed the assault, and called for assistance. As Don Pedro de Valdes made towards the San Juan to help her, his ship collided twice with Biscayans, and lost her foreyard, bowsprit, halyards and forecourse. The Nuestra Señora del Rosario was a big 1,150-ton nao, a multipurpose vessel now armed for war, and carried about 450 crew and fifty-two guns. Her men struggled to fit a new forecourse and contain the other damage, but the sea grew rougher and the wind intensified, and the foremast suddenly cracked close to the hatches and crashed against the mainmast. The ship was now in real distress, and Don Pedro fired three or four guns to signal his plight, begging Medina Sidonia to wait for him. But the admiral had the fleet to think of, and although his efforts to have the Rosario taken in tow failed, he held his eastward course and gradually left her to the rear.

She was no mean vessel to lose. Apart from being one of the largest and most heavily armed in the fleet, and the flagship of one of the Armada’s leading officers, one whose reputation was probably only surpassed by those of Recalde and Oquendo, the Rosario stored about a third of the Armada’s money. Her captain, Vicente Alvarez, said she carried 52,000 of the king’s ducats in a chest, 4,000 reals, [about 400 ducats] belonging to Alvarez and other gentlemen, and a store of precious jewels and apparel. Don Pedro, who served in her as admiral, gave a more modest figure: 20,000 ducats, and silver vessels worth another thousand. In either case there were few ships in the fleet so wealthy.

The other accident cost Medina Sidonia a second prime warship, one of Miguel de Oquendo’s Guipuzcoan squadron, called the San Salvador. For some reason – whether through accident or sabotage was never established – she caught fire and the great quantity of powder she carried went up in a vast explosion that ripped away her stern and two decks and killed about two hundred men. Boats were ordered to her rescue, and the fire was extinguished, but all that remained was a burned out shell, stinking of charred wood and bodies. Most of the survivors of her crew were evacuated, but with the English fleet closing, the Spaniards abandoned the San Salvador to the winds and current with some dreadfully injured men still aboard her.

Although neither loss had been directly caused by English action, and the Armada was pressing relentlessly onwards, Medina Sidonia may have thought more seriously about the possibility of a haven such as the Isle of Wight. There would be more battles, more casualties, and no one could guess what shape the Armada would be in when it reached Parma. Drake and Howard were worrying about it too, and talking it through in council. They were short of powder and shot, and the action off Plymouth suggested that they were going to need more of it than they had believed. It was likely that there would be a greater battle off the Isle of Wight, if Medina Sidonia threatened to run into Spithead, and although the English had now been reinforced by the ships that had not managed to quit Plymouth in time for the first débâcle, it was unwise to press the Armada too closely at this time. Yet they must follow it and look for opportunities, and it was decided that Sir Francis Drake should lead. During the night of 21–22 July he would keep his stern lantern alight to mark the course for the rest of the fleet.

During the darkness Sir Francis dogged the rear of the great Armada, as it bore slowly along, past Start Point and the Skerries Rock, and through Start Bay. Then something happened. The watch of the Revenge reported lights to the right, perhaps three or four ships sailing abreast, but what ships? And to what purpose? One possibility was that some of the Spaniards were working to windward of the English in the dark, just as Drake and Howard had done the previous night, and Drake deemed it his duty to investigate. Since he did not wish to lead the whole of the English fleet from their course, he ordered the lantern of the Revenge to be extinguished, and put about towards the strange vessels, bringing with him only the Roebuck and one or two pinnaces.7

The quarry turned out to be harmless, merely German freighters, and Drake eventually started back to rejoin the fleet, probably feeling not a little chagrined. But he did not return empty-handed, for at dawn of 22 July he came upon Don Pedro’s great nao, Nuestra Señora del Rosario, which had dropped out of the Armada and lay to the south so that the English fleet had passed her by. Don Pedro was in a poor position indeed. His ship was powerful, and her tonnage exceeded the Revenge and Roebuck combined, but he was virtually without sails, his mainmast was damaged and his foremast and bowsprit had gone. A few ships and pinnaces had tried to take the Rosario in tow during the night, but fear of falling behind Medina Sidonia as well as poor weather and big seas frustrated their efforts, and the last of them had made off about nine o’clock the previous evening, when an English ship appeared. Captain John Fisher, of the 200-ton Margaret and John, found the nao without lights, but as he ranged alongside, her towering castles defied boarders, so he fired some arrows and musket balls at her from close range to test for a response. Two or three Spanish guns replied, Fisher delivered a broadside, and then the English ship withdrew and lay to, close enough to hear the voices of the Spaniards despite a brisk wind. The Rosario was far too strong a ship for the Margaret and John, and after a while Fisher set off to return to Howard.

Then, at dawn, Drake arrived. Sir Francis wasted no time. He summoned Don Pedro to surrender, and when the Spaniards asked for terms, told them he had no time to parley, but they had the word of Francis Drake that they would be well treated. This was enough for Don Pedro. Even though he had a superior force, there was no shame in surrendering to the greatest seaman of the age, and the Spanish admiral and several of his officers were taken aboard the Revenge, where they were received with trumpets and music. Don Pedro kissed Sir Francis’s hand and complimented him upon both his exploits and his humanity, and the stocky Englishman then embraced his vanquished foe, and directed him to make use of his own cabin, where a banquet was shortly served.8

Nearly twenty years later, in depositions taken before the Barons of the Exchequer, some of Drake’s old crew recalled the capture of the Rosario. With a fierce loyalty to the memory of their little captain, they highlighted his gracious treatment of Don Pedro. James Baron told how the grandee had come aboard the Revenge for talks after Drake had pledged his safe return to the Rosario should he decide not to yield.

The said Sir Francis entertained the said Don Pedro in his cabin, and there, in the hearing of this deponent, the said Sir Francis Drake did will his own interpreter to ask the said Don Pedro in the Spanish tongue whether he would yield unto him or no and further to tell him if he would not yield he would set him aboard again. Whereupon the said Don Pedro paused a little while with himself, and afterwards yielded unto the said Sir Francis Drake and remained with him as a prisoner.

George Hughes, another Drake hand, remembered that when they had encountered the Rosario, ‘straying and distant a little from the rest of the Spanish fleet’, they had willed it to yield. Don Pedro had accordingly

sent some of his captains unto Sir Francis Drake to show him upon what conditions he would yield, but Sir Francis Drake not accepting of any such conditions & Don Pedro distrusting the danger ensuing, [Don Pedro] came voluntarily into the said Sir Francis Drake’s ship and yielded himself prisoner unto him, together with his own ship & company. And after that this deponent [Hughes] heard it commonly reported in the ship that the said Don did say & give out in speech that since it was his chance to be taken he was glad that he fell into Sir Francis Drake’s hands.9

It was only after the capture of the Rosario that Drake learned of the wealth that she carried. He decided to transfer it to the Revenge, where he could keep his eye on it, rather than risk its shipment to port, but how much actually came into his possession no one can say. Some of the booty was undoubtedly purloined by the sailors who found, broke open and emptied the treasure chest. What remained was passed down in thin canvas bags into the skiff. There more of it probably went astray during the confusion of the passage to the Revenge, so many men piling into the boat that it was in danger of capsizing as it laboured through a rough sea. George Hughes even accused the Spaniards of plundering the treasure themselves when they perceived that they must be captured, ‘for that he heard … that one of the Spaniards that was taken at that time had of the gold as much about him as did afterwards pay for his ransom.’10

Once the treasure had been removed, the prize was conveyed to Torbay by Captain Jacob Whiddon of the Roebuck. Drake rejoined Howard later on the 22nd. The morning had been eventful for the Lord Admiral. Lacking Drake’s light some of the English ships had been following the stern lights of straggling Spaniards during the night, while others had hove to. Dawn found them in disorder, with Howard’s Ark Royal, the Mary Rose and the Bear so far forward that the nearest Spaniards were within gun range, off Berry Head, and the rest of Elizabeth’s fleet well behind. As for Drake, he was nowhere to be seen. Howard and the advanced ships battled back to their main body, where the Lord Admiral had his second surprise of the day: Sir Francis Drake returning to the fleet with a Spanish admiral as his prisoner, one of the enemy flagships as his prize, and a fortune in booty! If Howard listened soberly to Drake’s adventure, and entertained Don Pedro whom Sir Francis introduced, he may have smiled to himself, for who in the fleet but Drake would have been likely to pull it off?

Drake’s independent action on the night of 21 July may have given the English their first and richest prize of the campaign, but it had also endangered the fleet and it triggered a wave of envy among the ship captains. It was unclear whether the spoils would be distributed to the immediate captors, Drake and Whiddon and their men, or to the fleet as a whole. Fisher of the Margaret and John protested that he had a claim, but none was more enraged than Frobisher, who fulminated with unbridled passion against Drake’s good fortune. He shouted that Drake ‘thinketh to cozen us of our shares of fifteen thousand ducats, but we will have our shares, or I will make him spend the best blood in his belly, for he hath had enough of those cozening cheats already.’ Sir Francis heard about it, and had Frobisher’s comments written down, possibly with a view to acting against him, but nothing came of it, and others saw the whole matter differently. When news of the Rosario’s capture reached London bonfires were lit in celebration.

There was one unlooked-for and less constructive consequence of the fall of the Rosario: it reinforced the excessive caution of the English fleet. Don Pedro’s ship was one of the most powerfully armed in the Armada, with some fifty-two guns, most of them heavy-shotted pieces capable of delivering a fearsome close-quarter broadside. Although mounted on unwieldy carriages, those guns still gave a deceptive picture of the Armada’s strength, a picture unfortunately supported by the San Salvador, the other Spaniard that fell into Howard’s hands through mishap. Neither ship was at all representative of the Armada generally, but together they gave the English a vastly inflated opinion of Medina Sidonia’s fire power. Drake had no doubt that the Spaniards would be beaten, but he was playing for enormous stakes, and did not intend to take unnecessary risks. He and his colleagues continued to believe that their best plan was to stay at a distance, knocking the Spanish ships to pieces and risking close action only when single enemy vessels or groups of vessels could be mobbed and overwhelmed. The plan was certainly safe, but it was also inadequate to inflict serious damage on the Spanish fleet, let alone defeat it. Indeed, Medina Sidonia was rearranging his fleet to make those tactics even more difficult. The horns of the Armada, vulnerable to splintering before a determined assault, were brought in to give a more solid, compact formation consisting of main and rear bodies. Whatever lessons the contending fleets had learned from the first exchange were soon to be put into practice, because as dawn broke on 23 July they prepared for a furious second round off Portland Bill.11

The wind had gone to north-east, presenting the Armada with the weather-gauge, and in the first light Howard led his fleet north-westerly towards the shore to try to regain the attacking position. But Medina Sidonia anticipated the move, and headed the English off, forcing Howard to go about and turn eastwards on the opposite tack towards the sea. Now was the time for the Spaniards to attack, with the wind in their favour and the Lord Admiral’s ships straggling to leeward, and they tried to do so. But they were far too slow. The dexterous English ships slipped nimbly away, leaving their foremost attackers astern.

Nevertheless, Howard’s manoeuvre had failed, and he had got himself into a difficult spot. He could not outflank Medina Sidonia and fell back to leeward to reform, but in doing so he left a detachment of his ships behind, inshore, close to Portland Bill. They included Martin Frobisher’s Triumph, the largest ship in the English fleet, and Flick’s Merchant Royal. The Spanish admiral ordered up his four big fifty-gun galleasses to attack them, and Hugo de Moncada led them forward propelled by 1,200 oarsmen. Now, however, Frobisher’s gunners found their mark. Their smaller, handier gun carriages enabled them to run out the pieces, discharge them, pull them back in for reloading and run them out again fast enough to maintain a constant fire, and they had an obvious target – the massive banks of oars on the galleasses as they crept menacingly forward. Soon the English shot was ravaging Moncada’s vessels, splintering the oars and maiming rowers, and the much-vaunted galleasses faltered, and yet still Frobisher and his comrades were in danger. For seeing Moncada wilting before the superior fire power of the English, a number of other Spanish captains began to bring their guns to bear upon the small group of enemy ships.

The wind saved the stubborn Yorkshireman from further punishment, for about ten o’clock in the morning it shifted to south-south-west, restoring the weather-gauge to the rest of the English fleet and enabling it to counter-attack. Drake, who had apparently led about fifty ships out to sea, now suddenly threw himself into the battle, launching a vigorous assault upon the Armada’s southerly flank, ‘so sharply,’ says the presumed Howard narrative, ‘that they were all forced to give way and bear room.’ Medina Sidonia’s attack on Frobisher was now diluted, as he transferred ships from inshore to meet Drake’s division, and Howard came forging forward with the wind behind him to rejoin the combat.

The battle had now swung the other way, and it was the Spanish admiral, and no longer Frobisher, who was in danger of being overwhelmed. Towards Medina Sidonia’s San Martin came Howard’s Ark Royal, Robert Southwell’s Elizabeth Jonas, George Fenner’s Leicester Galleon, Edward Fenton’s Mary Rose, Sir George Beeston’s Dreadnought, John Hawkins’s Victory, Richard Hawkins’s Swallow, Lord Thomas Howard’s Golden Lion and others in line-ahead formation, even eventually Drake and his followers who had no sooner seen the Armada’s southern flank reinforced than they switched their attention elsewhere. In turn they entered the action, blasting away into the San Martin, riddling her with no less than five hundred shot, according to the chief purser of the Armada, Pedro Coco Calderon. The Duke of Medina Sidonia could not get his ship round to make use of both broadsides, and replied with eighty balls from one side of the flagship only. For an hour the English pummelled the San Martin, enveloping her in so much gunsmoke that the other Spaniards could not see her, but in the middle of the afternoon the fight ended. Frobisher had been released, and Medina Sidonia and his ships slipped away to leeward. Howard did not chase them. His fleet had fired off most of its shot, and was probably exhausted.

The action off Portland Bill revealed in stark relief the incapacities of both sides. It had been fully joined, hard fought – no partial encounter such as Plymouth had witnessed. There could be no doubt that both sides had made a serious attempt to break the other, and the Howard narrative emphasized that

it may well be said that for the time there was never seen a more terrible value of great shot, nor more hot fight than this was … the great ordnance came so thick that a man would have judged it to have been a hot skirmish of small shot, being all the fight long within half musket shot of the enemy.

The battle had not only been well sustained, but at various times produced favourable circumstances for both sides. It had opened disastrously for the English, with Howard beaten off and Frobisher isolated, but the change in the wind and Drake’s attack had changed the complexion of the fight, and facilitated the heavy assault on the San Martin and its immediate consorts. And yet to what purpose? Neither fleet had sunk or crippled an enemy, and at the end of the cannonade the Armada was bearing away before a strong evening breeze at the south-west while the English were almost out of ammunition. Under-armed, the Spaniards had inflicted little damage upon Elizabeth’s ships, and even the Triumph, for much of the time the prime target for the Armada, was so little injured that she could fight just as hard two days later. Even more remarkably, however, the Spanish San Martin suffered only peripheral damage: a few holes to be plugged in the hull, some rigging and a mainstay cut, and a flagstaff missing! In all the Spaniards reported a loss of only fifty killed in the engagement.

The conclusions are inescapable. If the Armada’s armament and gunnery were unable to do the English much harm, no more was that light shot fired by Howard and Drake doing much to Medina Sidonia. Admitting some exaggeration of the closeness and ferocity of the encounter by the witnesses, and the indifferent gunnery of the English ships, the result of the battle of Portland Bill clearly denoted a need for new tactics on the part of Elizabeth’s admirals. They would have to move in close and give their guns some hitting power, and they needed a manouevre that would break up that tight Spanish formation.

Make no mistake about it, Portland Bill was a victory for Medina Sidonia, if a poor one. It must be remembered that his task was to proceed through the Channel to link with Parma, and that was what he was doing; it was the job of Howard and Drake to stop him, to splinter or destroy his fleet, and in two engagements they had failed to accomplish it. And another shuddering thought may have occurred to Sir Francis, for ahead lay the Isle of Wight – the next danger point – and here he was, trying to replenish his powder and shot with the rest of his fleet, and wondering what to try next.

He could not leave it like that, and at dawn the following morning he tried again, committing his division without the support of the rest of the fleet, just as the Armada approached the Isle of Wight. This first battle of the Isle of Wight, on 24 July, was totally ignored in the Howard narrative but features in several Spanish accounts, of which the fullest was given by Captain Vanegas:

On Wednesday, August 3rd [New Style], once it was daylight, the enemy once again pounded our rear-guard, and then came to our help the good Oquendo and the good admiral, and Don Alonso de Leiva and Bertendona, and two galleasses and the Duke of Florencia’s galleon, and the leading storeship, on board which was the good Guan de Medina, leader of all the armada’s storeships, and two other galleons of the squadron that came from Castile. The Duke ordered the admiral’s ship to put about to help the rearguard, and as the enemy saw our royal ship turn it turned in flight and it was understood that it had received quite some damage. This was realized more by the fact that it only wished to fight from outside the range of the artillery. That day our vice-admiral’s ship fired one hundred and thirty cannon shots, and in both armadas more than five thousand cannon-balls were fired. In our armada they killed sixty people and wounded another seventy. The leading storeship was embayed on a lee-shore and more than forty cannon shots were fired at it. The enemy’s flagship had its main lateen-yard smashed by a shot which our vice-admiral’s ship fired at it. After the enemy had withdrawn it put to sea beamside for about four hours, getting itself ready.12

Even this garbled and exaggerated account permits two important conclusions: Drake fought a considerable action that day, causing (if the figures can be believed) greater casualties than the Spaniards received at Plymouth, Portland Bill or the succeeding battle off the Isle of Wight, but, notwithstanding, the English remained wedded to the tactics of harassing stragglers or small units with a relatively ineffective fire over long distance.

The battle had begun about dawn and lasted for up to two hours. With the wind in his favour, Drake led an assault upon the Armada’s rearguard, under Recalde and Leiva, singling out for particular attention El Gran Grifon (Juan Gómez de Medina), the flagship of a squadron of hulks, a pitching merchantman armed with thirty-five guns and carrying 279 men. The English beset her as wolves bait a wounded bison, putting (it was said) forty shot into her, but other Armada ships were also engaged, including fighting galleons and galleasses. Initially, the Spaniards preserved their order, deigning to reply to the English only with their stern guns, but eventually Medina Sidonia decided that a more positive response was necessary and began to put about. Drake discreetly retired. The wind was beginning to fail, he may have sustained some damage (the Spaniards thought they had slashed some of the Revenge’s rigging and brought down a yard), and he was probably low on ammunition and powder. The evidence does not suggest that the attack was much more successful than the fiasco off Portland Bill. Medina Sidonia’s progress had been unchecked, and even the wretched El Gran Grifon lived to fight another day, but what was worse, the battle gives no indication that Sir Francis had learned anything from his previous engagements.

It is possible to imagine a furrow across the brow of Sir Francis Drake after this latest attack, for he knew a critical moment in the campaign was approaching. Hours ahead lay the Isle of Wight, which had often seemed the logical first step in any invasion of England from across the Channel. Little more than forty years before it had been occupied by the French. Now, its governor, Sir George Carey, had been improvising land defences, and was even then dispatching some ships to reinforce Howard’s fleet. Ammunition, provisions and supplies, all badly needed, were also passing to Elizabeth’s ships, and spectators had begun to gather on nearby cliffs to watch their fleet manoeuvre against the Armada in what would be a crucial contest. Would Medina Sidonia try to enter the Solent and seize the Isle of Wight? Could Drake and Howard drive him beyond, further into the Channel, or destroy him utterly? Those questions were worrying Drake too. Three battles and still the Armada held its formation, drew closer to its goal. Three battles, and yet Medina Sidonia’s only loss by enemy action had been the Rosario, and that more through accident. Sir Francis was thinking hard, getting his ship refitted, going over in his mind the local tides, currents and shoals. He had sailed these waters many times, ever since he was a boy, and he wondered how they could serve him. If the Armada made for the Solent, it would be by the eastern passage, and a little beyond lay some dangerous shallows … the Owers Banks.

The dissatisfaction of the English commanders found tangible expression on 24 July, as Howard reorganized his fleet into four divisions to give it greater co-ordination. Perhaps the disciplined order of the Armada had been some inspiration, but the difficulties of handling such large numbers of vessels would have pinpointed the problem anyway, for the Tudor navy had no efficient method of signalling and captains were more frequently working as individuals than as members of a team. Now Frobisher was promoted to the position of squadron commander, and placed in shore, while Drake took the seaward wing, from his point of view by far the best position since it gave greater freedom of manoeuvre. Howard and Hawkins commanded the centre.

On 25 July the new system was blooded. Both fleets were south of the Isle of Wight, and now if ever the Duke of Medina Sidonia must decide whether he wanted to try for the Solent. But the beginning of the day was sluggish, for dawn found the ships becalmed off Dunnose Head, and without wind Drake and Howard were denied one of their principal advantages – the speed and mobility of their ships. The Spaniards, however, could again call upon their galleasses, although their commander, Moncada, must have still been reflecting upon his disastrous showing off Portland Bill.

Conditions on that important day seemed slightly to favour the Armada, but it had a shaky start, for two of the ships were straggling, the Portuguese galleon San Luis and an armed merchantman, the Santa Ana. Nearest to them was the squadron of John Hawkins, and the calm did not deter the old veteran from making an attack. Boats were lowered, and slowly some of Hawkins’s grèat ships were towed towards the Spaniards. As they got close a musket fire from the Armada ships began to spatter upon the long boats, and drove them away, but the warships they had tried to bring to action remained in an advanced position. Moncada’s time had come, and the galleasses ominously advanced, their blood-red sweeps rhythmically cutting the water beneath red upper works and loose sails adorned with the ‘bloody sword’. In their support edged Leiva’s Rata Encoronada. Howard, whose squadron was next to Hawkins, took up the challenge and his boats pulled the Ark Royal and Golden Lion into a position to support Hawkins. From both sides the guns rumbled, but despite the roar and banks of powder smoke little damage was done. The galleasses rescued the Armada stragglers and brought them into the fleet, but no more, and Howard had the satisfaction of blowing away one of the enemy’s stern lanterns!

When the wind freshened it blew from the south, and Medina Sidonia advanced in support of Leiva and Moncada. For a while he paid the price of his boldness, for the duke took the fire of several English ships. His mainstay was cut and some men were killed, but then his temerity paid dividends, for as his rearguard came to join him the English centre retired. Only one English ship was left in danger by these actions – predictably Frobisher’s Triumph which had crept too far forward inshore during the poor wind and was now being left to leeward by the most westerly of the Spanish ships. Some of Frobisher’s followers realized their mistake and withdrew in time, but their commander was virtually cut off, the eastward tide running alongside the Isle of Wight pressing him further into danger. This time Martin Frobisher was seriously worried. Although the Bear and the Elizabeth Jonas were close enough to fire in his defence, he was in danger of being overwhelmed, and lowered his ensign to signal for assistance and fired distress guns. Small boats were put out, eleven in all, to try to tow him away.13

At this stage the performances of both sides had been lack-lustre, but the Armada was in the stronger position. It had the largest of the English vessels in difficulties, and there appeared nothing to prevent Medina Sidonia entering the eastern channel of the Solent if he desired. Unfortunately for the duke, winds are commanded by no man, and a freshening breeze suddenly rescued the English. As the sails of the Triumph began to fill, Frobisher was able to demonstrate the superior sailing qualities of Howard’s fleet, for he called in his boats and retired so quickly, according to a Spanish eye-witness, that by comparison the fastest ships of the Armada seemed to stand still. That same wind enabled the English to make a desperate bid to drive Medina Sidonia beyond the Isle of Wight. Sir Francis Drake had been quietly working his way out to sea with his division, waiting for his opportunity, and now he launched a vigorous charge upon the seaward flank of the Armada, marked by the Portuguese galleon San Mateo, and began crowding the whole Spanish fleet north-easterly towards Selsey Bill. Some of the Spaniards believed he was trying to corner the Armada, but Medina Sidonia seems to have realized the frightening import of Drake’s manoeuvre, for just ahead – directly in the path of the Spanish fleet – there appeared signs all seamen learned to heed from their first days afloat, signs of dangerous and extensive shoals, the treacherous Owers Banks. ‘El Draque’ was running the Armada aground! The wind, which blew from the south-west, and tides were in league with him, and Medina Sidonia had but one safe escape: to put about and steer south-south-east with all speed, forgetting any plans to enter the Solent. Before the end of the morning the Armada had saved itself, but ploughed solidly eastwards, with the Isle of Wight astern.

The battle was over, and in one sense it was a victory for the English, for they had successfully protected the Isle of Wight. Howard began knighting some of his officers, Hawkins and Frobisher, Lord Thomas Howard and Lord Sheffield, his kinsmen, and a few others (Drake, of course, he had no power to reward), but in truth neither side could take too much credit for what had been, Sir Francis’s manoeuvre excepted, a rather scrambling, undistinguished encounter. Nothing could disguise the fact that four battles had left the Armada more or less unscathed, and that the English tactics of using light artillery at less than point-blank range, and of concentrating largely upon straggling or isolated groups of ships, had failed. In the last engagement none of Medina Sidonia’s vessels had been seriously damaged and he had lost only about fifty men killed. Drake and Howard had won some strategic victories, but had been unable to break the Armada’s order or prevent its passage along the Channel. The English admirals sent ashore for more powder, shot and supplies, and looked forward to a reinforcement from Lord Henry Seymour and Sir William Winter, whose squadron lay ahead, but above all they needed a new plan of battle.

Yet Medina Sidonia, Recalde and their officers were no less perplexed, and an air of desperation was creeping into the duke’s letters to Parma. Whether the duke had really intended to seize the Isle of Wight is not known, but after Drake’s attack he had no adequate port before him, and while the English had been repelled the Armada had been able to do no appreciable violence. The enemy gunfire was weak, but the Spanish reply was far, far worse, and the Armada’s main weapon, its soldiers, had remained redundant. ‘It was impossible to come to hand-stroke with them,’ reported Medina Sidonia’s journal. To Parma the admiral wrote, ‘The enemy has resolutely avoided coming to close quarters with our ships, although I have tried my hardest to make him do so. I have given him so many opportunities that sometimes some of our vessels have been in the very midst of the enemy’s fleet, to induce one of his ships to grapple and begin the fight, but all to no purpose.’ Another officer sadly reflected that the English ‘displayed some signs of a desire to come to close quarters, but did not do so, always keeping off and confining the fight to artillery fire. The Duke endeavoured to close with him, but it was impossible in consequence of the swiftness of the enemy’s vessels.’14 It was unfortunate, but from the Spanish point of view, it is difficult to see how a closer action, other than a boarding action, could have done anything but multiply their misery, for the handiness of the ships would have simply permitted the English artillery to reap greater slaughter at point-blank range. It was almost impossible for the Armada to defeat Howard’s fleet severely.

This meant that the overall prospect for the Armada was extremely bleak, for if Drake and Howard could not be neutralized, how could they be prevented from interfering with the passage of Parma’s army across the Channel, and perhaps from destroying it? Medina Sidonia forlornly pinned his hopes upon Parma, and after his last battle wrote to the general begging him to come out and help the Armada push back the English, and perhaps at last to seize the Isle of Wight. In any case, he wanted forty to fifty light-draught flyboats to help him defend any anchorage he might find for the fleet.

But Parma can only have judged the letter somewhat pathetic. His river craft could barely serve at sea, let alone take on Drake. It was the Armada’s job to clear the passage, not the army’s, even though the tone of the admiral’s letter suggested that the task was beyond him. Parma set in motion some fresh supplies of ammunition for the Armada, and on 28 July left Bruges for the coast to supervise the embarkation of 16,000 men at Nieuport, Sluys, Antwerp and Dunkirk, all flattering themselves they were bound for England. It is doubtful if the general himself believed it. The Armada did not look as if it was capable of making a way for him, and even if the English were held off there were still those Dutch ships waiting to spring on Parma’s barges in the shallows, where Medina Sidonia’s warships could not sail. But Philip had ordered, and Parma must go through the motions.

So must the Armada, and in growing despair it steered for Calais.

1 Lloyd, ‘Drake’s Game of Bowls’; Tytler, Life of Raleigh, 88–9.

2 Howard, ‘A Relation of Proceedings’, Laughton, State Papers Relating to the Defeat of the Spanish Armada, 1: 1–18. The relation is unsigned, but evidently was composed from Howard’s information.

3 Spanish accounts can be found in Duro, ed., La Armada Invencible; Hume, Calendar of Letters and State Papers … in the Archives of Simancas, vol. 4; and Oria, La Armada Invencible. Naish, Naval Miscellany, prints the Ubaldino narrative adapted by Drake.

4 Howard to Walsingham, 21 July, 1588, Laughton, 1: 288–9.

5 Drake to Seymour, 21 July, 1588, Ibid, 1: 289–90.

6 Don Pedro de Valdes to the king, 21 August, 1588, Ibid, 2: 133–6.

7 Some writers, eager to attack Drake, have accepted at face value Martin Frobisher’s unsupported insinuation that Drake abandoned his position for the sole purpose of capturing the Rosario, and that Sir Francis’s story about the freighters was invented. It is worth remembering that Drake could not have known of the wealth aboard the Rosario before he captured her, and that his account is fully supported by Matthew Starke (deposition, 11 August, 1588, Laughton, 2: 101–4). Frobisher’s allegations (recorded by Starke) were stimulated by jealousy of the vice-admiral and a fear that he, as the captor of the Rosario, would claim the full amount of the prize money for the Revenge instead of sharing it with the fleet (petition of the officers of the Margaret and John, August, 1588, Ibid, 2: 104–7). No one else seems to have raised the charges, and Howard thought so little of them that he allowed Drake to hold the watch for the fleet on subsequent occasions, including the night after the decisive battle off Gravelines. Further vindication of Drake’s story is provided by the deposition of Hans Buttber, who seems to have been skipper of one of the freighters Drake investigated on the night of 21 July (Klarwill, Fugger News-Letters, 2: 168). Buttber stated that he was bound for Hamburg from San Lucar, when Drake intercepted him on 21 July, ‘just after the latter had had an engagement with the Spanish Armada.’ Sir Francis told Buttber to attach himself to the English fleet for safety, and the German was present at the capture of Don Pedro. On 26 July Drake allowed him to proceed on his journey, providing he took a message with him for Seymour’s squadron off Dover. It seems to me that the evidence supporting Drake’s explanation is stronger than any opposing it. See also Benson, ‘Drake’s Duty. New Light on Armada Incident’.

8 For details of the capture of the Rosario I have drawn upon the Drake Ubaldino narrative, an account in Purchas, Purchas, His Pilgrims, 19:488–9, and the depositions taken in the lawsuit Drake v. Drake in 1605, Public Record Office, E.133/47/3–5. The latter, although containing a good deal of Rosario material, are not as informative as might be supposed. The depositions were taken seventeen years after the event and much of the testimony, in any case, was hearsay. The intention of the witnesses, moreover, was to shore up the claims of one or other of the contending parties (Francis Drake of Esher and Thomas Drake), not to leave an objective record of events for posterity.

9 There is a transcript of the deposition of James Baron of Stonehouse, Devon, 7 October, 1605, in the papers of Lady E. F. Eliott-Drake: Drake Papers, Devon County Record Office, Exeter, 346M/F534. I have not seen the original. The deposition of George Hughes of Tottenham Court, Middlesex, 13 November, 1605, is in the Public Record Office, E.133/47/3. Both Baron and Hughes sailed in the Revenge during the Armada campaign. There are also accounts of the surrender of Don Pedro in the depositions of Simon Wood of Bushe Lane, London, 9 November, 1605, and Evan Owen of Esher, not dated, at E.133/47/3 and E.133/47/4 respectively, but both are at best secondhand. Wood served in the campaign, but aboard the Leicester Galleon. Owen, who took no part in the campaign at all, purportedly deposes to what he had heard ‘from Don Pedro’s own mouth’.

10 Deposition of George Hughes, 10 February, 1606, E.133/47/4. Since the total amount of money carried by the Rosario is not known it is impossible to estimate how much went astray. Drake surrendered 25,300 ducats of it to Howard. Hughes said that Drake delivered the plunder to the Lord Treasurer and that the queen later authorized Howard and Drake to ‘bestow some of the same treasure upon the commanders, gentlemen & others that were in that voyage, whereof this deponent had a part’. It does indeed appear that a reward of 4,667 ‘pistolets’ (ducats) was shared amongst the fleet (Hist. MSS Commission, Calendar of the Manuscripts of the Marquis of Salisbury, 3: 364). After Drake’s death, the Drakes of Esher, disappointed at the fruits of their legacy from Sir Francis, tried to obtain money from Thomas Drake (the admiral’s brother and heir) by preferring a bill against him in the Exchequer Chamber alleging that Drake had embezzled some of the money from the Rosario. These accusations were vigorously contested by Thomas, but ultimately the prosecution collapsed because of his death. Although it is unlikely that Drake did not secure a respectable reward for his capture of the ship, nothing like a convincing case was ever made out for his dishonesty. Although the men of the Roebuck were suspected of purloining plunder from the Rosario, there appears to have been no contemporary allegation that Drake did not surrender such money as had come into his hands (Dasent, ed., Acts of the Privy Council, 16: 363).

Sir Francis did, however, successfully persuade the queen to allow him the privilege of ransoming Don Pedro. Most of the Spaniards who had come aboard the Revenge with the Spanish admiral were conducted to London by two of Drake’s associates, Thomas Cely and Tristram Gorges, but Don Pedro and a few others remained with Sir Francis until the fighting was over, when they were landed at Rye. Don Pedro and two companions were eventually housed at Esher at Drake’s expense. Simon and Margaret Wood, then both in Drake’s service, later deposed that Sir Francis paid Richard Drake of Esher £4 a week for the grandee’s diet. Margaret, for example, stated that Richard’s servants came weekly for the money to Drake’s house in Dowgate, ‘where this deponent then dwelt’. (Deposition of Margaret Wood, 9 November, 1605, at E. 133/47/3.)

It is worth mentioning that Don Pedro was humanely treated by Drake. Because of the Spaniard’s high status, the queen was reluctant to release him before the war ended, and he remained with the Drakes until early in 1593, notwithstanding Sir Francis’s efforts to get him exchanged and sent home as soon as possible. During those years Drake attended to Don Pedro’s complaints, and sent him provisions. There are references to Don Pedro walking in St James’s Park with Sir Francis and the queen, hunting, and meeting Lady Drake, Dom Antonio, Sir Horatio Palavicino, Sir John Norris and other notables who visited Esher. When he was finally ransomed for £3,550 (plus maintenance at £400 per annum), sums that Sir Francis allowed the Drakes of Esher to keep, the Spaniard was given a farewell banquet by the Lord Mayor of London. See Martin, Spanish Armada Prisoners, ch. 5. This book provides an excellent account of the disposal of the prisoners and plunder from the Rosario.

11 Martin and Parker, Spanish Armada, 212, were the first historians to develop the connection between the capture of the Rosario and English battle tactics in succeeding engagements, but I cannot agree with their conclusions. They contend that the Rosario suggested the weaknesses of the Armada, and encouraged the English to adopt more aggressive tactics. Inasmuch as the prize carried some fifty bronze and two iron pieces of artillery, and was unusually heavily armed, I infer that it conveyed a false picture of the Armada’s strength and reinforced caution in the English fleet. And far from the succeeding battles of Portland and the Isle of Wight displaying improved tactics on the part of the English, I believe that they showed no significant advances on the tactics employed off Plymouth. I must add, however, that I depart from the judgement of Martin and Parker only with the greatest hesitation.

12 Translated from Duro, 2: 384–5. Other accounts of this battle may be found in Pedro Estrade’s narrative (Oppenheim, Monson, 2: 299–308): Jorge Manrique to Philip, 11 August, 1588 (Hume, 4: 373–5); Pedro Coco Calderon narrative (Ibid, 4: 439–50); and Medina Sidonia’s relation (Laughton, 2: 354–70).

13 For tides, see Williamson, Age of Drake, 334.

14 Medina Sidonia to Parma, 4 August, 1588, and Manrique to Philip II, 11 August, 1588, Hume, 4: 360, 373–5.