Anybody who wants to write articles for newspapers and magazines would probably benefit from understanding the history of these media. This section examines the history, status quo, and possible future of the American newspaper and magazine industry. Although there’s considerable thematic overlap between movements in both of these industries, for ease of comprehension, I will separately examine newspapers and magazines.

Before I begin, I want to stress a point: In this book I tout the use of premium encyclopedic sources rather than Wikipedia. Although Wikipedia is freely available and covers a gamut of topics, not all the information on this site is transparent, verifiable, or coherent. As a testament to the power of the “Old Media,” I gathered much of the compelling historical information presented in this chapter and others from the Encyclopaedia Britannica (a wonderful secondary source to which I have a subscription).

The beginnings of the American newspaper are deeply tied to the revolutionary efforts of the United States. While America was still under colonial control, the British did their best to suppress the colonists’ free speech. For example, in 1690, Benjamin Harris attempted to publish Publick Occurrences Both Foreign and Domestick—an attempt which was quickly thwarted by the governor of Massachusetts. Ultimately, this suppression of free speech served to fuel the democratic fervor felt by the founding fathers.

Early colonial editors were interested in both recording the history of the American Revolution for future posterity and supporting the efforts of the revolution. In 1719, Benjamin Franklin’s older brother James helped establish the Boston Gazette, and the Boston Tea Party was planned in a back room of the newspaper.

The First Amendment guaranteed both freedom of speech and the press. Newspaper editors capitalized on this newfound freedom, and by the early 1800s, many newspapers became homes of political criticism and attack. Eventually, however, the focus of newspapers shifted from bolstering democracy to making money. In the 1800s, newspapers could be grossly divided into two categories: serious publications and commercially successful publications. At this time, newspapers started hiring journalists to create content. Many of these journalists became revered in their own right, and during the Civil War, some journalists who covered and helped prevent the atrocities of war were even more celebrated than the soldiers whom they covered.

Not all newspapers could afford to employ full-time journalists. Consequently, by 1851, Paul Julius Reuter—of Reuters fame—made use of the newly invented telegraph and set up shop in London, where he became a purveyor of information. Meanwhile, around 1846, a conglomerate of New York newspapers pooled their resources and shared content to cover the Mexican-American War. This conglomerate, initially called the New York Associated Press, eventually became the Associated Press. The Associated Press was instrumental in the introduction of syndicated news that was “objective” and reported on the bare facts.

Higher literacy rates, the telegraph, railroad transportation, and later inventions such as the linotype created an environment conducive to the growth of the American newspaper. In 1835, Benjamin H. Day published the first “penny press,” The New York Sun, which fed the common consumer’s hunger for human-interest stories.

Newspapers of this era did much to establish the foundations of modern journalism. In 1835, the New York Herald became the first newspaper to establish complete editorial independence from any political party. The New York Herald offered varied and entertaining content, including news and commentary packaged in sensationalistic form. In 1841, Horace Greeley established the New-York Tribune, which championed Greeley’s cause: the abolition of slavery. Meanwhile, in rougher frontier areas, newspapers such as the Chicago Tribune presented sensationalistic content to entertain their more adventurous readers. And in the South, newspapers such as The Atlanta Constitution rebuilt civic consciousness in the wake of the Civil War. Probably the single most noteworthy event during the era occurred when the editor of The New York Times refused and later exposed a five-million-dollar bribe from Tammany Hall politician “Boss” Tweed. By doing so, The New York Times helped establish its general and enduring sense of journalistic independence and integrity.

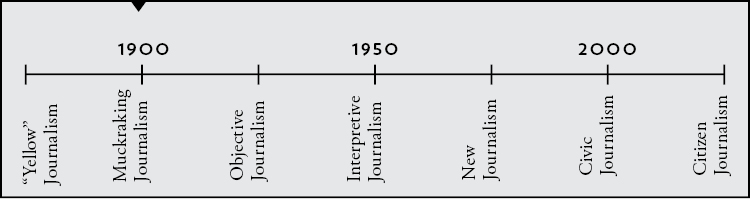

By the 1890s, the prominence of the newspaper editor made way for the reign of the press baron. Press barons often owned many newspapers and cared more about making money through circulation and advertising than reporting “hard” news. Enter the age of yellow journalism.

The term yellow journalism specifically refers to the ongoing war for readership and economic dominance that occurred between New York City publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. (Interestingly, the term “yellow” journalism is derived from an employment dispute that occurred between Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal that involved a cartoon titled “The Yellow Kid.” Both newspapers ended up publishing the cartoon.) Both men came up in rough and rugged frontier territories and infused their publications with a dramatic sense of sensationalism. But whereas Pulitzer was idealistic and did his best to maintain editorial independence, expose wrongdoing, and ascribe to some ideals, Hearst would do anything to sell papers. Hearst even went so far as to make up news stories to rile the United States into a war with Spain over Cuba.

Arguably, the era of yellow journalism offered little in the way of social import. Nevertheless, its influence can still be felt in Internet, television, and print sensationalism. For example, in 2013, when the government of Cyprus threatened to confiscate money from citizen bank accounts, the media had a field day and played on people’s fears. The sensationalistic media coverage caused people to make a run for the bank and to try to pull their funds. Furthermore, sensationalism changed modern print publication in meaningful ways. For example, the current use of banner headlines, colored comics, and plenty of illustrations is rooted in the practices of yellow journalism.

By the early 1900s, the era of yellow journalism died off and was followed by muckraking, an era of more serious journalism which exposed corruption and social hardship. Lincoln Steffens was an early muckraker whose 1904 book Shame of Cities examined corruption in government and instigated reform. During this period, publishers started to worry not only about the commercial success of their papers but also about their social importance. This change can be traced to two main developments. First, powerful publishers such as newspaper magnate Edward Scripps and Adolph S. Ochs of The New York Times made great efforts to distance themselves from the “bad” (yellow) journalism of the proceeding era. And second, the practice of journalism became more academic. Schools and societies of journalism started popping up, and along with a formal pedagogy came the sense that a journalist should serve the public interest.

Although objective and detached journalism remained popular throughout the Cold War, by the 1920s it started to become clear to newspaper editors and journalists that straight or objective reporting often meant little to audience members, especially when the paper reported on complex social, economic, and political developments. For example, in the wake of the Great Depression, readers needed help making sense of the New Deal. Later, with fascism on the rise, readers needed help making sense of what was happening in Germany, Italy, and Japan.

In order to help the public understand what was going on in the world, newspapers started to analyze news, and the practice became known as interpretive journalism. Although there was a subjective element to the practice that required journalists and editors to take stands on issues, such stands were frequently grounded in ideology that most people deemed as democratic and morally correct. At first, newspaper editors and journalists tread lightly into the realm of making judgment calls on the news, but as the years proceeded, experts and scholars felt more comfortable with the practice, especially when reporting on national and international issues. (When reporting on local issues, newspaper journalists and editors were more hesitant to interpret anything—a practice that changed with the rise of civic journalism in the 1990s.)

A win for the practice of interpretive journalism came when the “traditionalists” at the Journalism Quarterly, an academic publication, denounced most newspapers of the 1940s for not interpreting and analyzing the news. It should be pointed out, however, that some traditionalists were unconvinced about the value of interpretive journalism and whether its practice crossed the line from interpretation to advocacy. In fact, an article in the Nieman Reports, another academic journal, likened the practice to editorial writing.

Despite lingering concerns about the practice of interpretive journalism, by the 1970s, most prominent publications, including the New York Herald Tribune, Newsweek, and The New York Times, had embraced the practice and used it to report civil-rights issues, the Vietnam War, and Watergate. (In many publications, interpretive journalism came to be labeled “news analysis.”) Of note, interpretive journalism flourished when journalists and publishers started seeing the power of the practice to do good, especially when coupled with investigation and research. For example, Philip Meyer, a one-time correspondent with Knight Ridder newspapers, wrote the highly influential Precision Journalism, which relied on research and interpretation to expose crime.

By the mid- to late 1900s, the widespread popularity of interpretive reporting was one of two main changes within the realm of journalism and newspaper reporting. The era’s other big influence was the New Journalism movement, which was rooted in the form of literary journalism championed by writers of bygone eras, including Stephen Crane, John Reed, John Dos Passos, and James Agee. The advent of New Journalism centered around 1960s counterculture, drugs, sex, and the Vietnam War.

Authors such as Truman Capote, Joan Didion, Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson, and Tom Wolfe started writing nonfiction using narrative and creative-writing elements, including symbols, imagery, mood, and novel structures. In print (and in real life) these authors connected with their characters vicariously and also had unabashed points of view that reflected distinct worldviews.

In a 2001 article titled “‘New’ Journalism,” Scott Sherman writes, “New Journalism hit its stride in the heady period of the 1960s. It was a generational revolt against the stylistic and political restraints of Cold War journalism, a rebellion against the drab, detached writing of the big-city dailies and the machine-like prose of the Luce magazines.” Ultimately, the realization that journalism can incorporate storytelling elements influenced the writing of countless journalists. For instance, the influence of New Journalism is well evidenced in Jon Franklin’s article “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster,” which won the inaugural Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 1979. (You can find a copy of this article on Jon Franklin’s personal website.)

The 1990s saw two waves of change in most newsrooms. The first involved structural changes. In a 2000 article titled “Reader Friendly,” Carl Sessions Stepp writes, “Papers flattened management, knocked down turf walls, formed teams, and redefined titles.”

The second wave of change during the 1990s involved a focus on civic or public journalism. Community issues became central to stories. Sources were members of the community and no longer only “elite” or expert. Divisive issues were either avoided or tackled with a perspective specific to the community. A circumspect sense of community sensitivity pervaded newsrooms and dictated which stories were printed. Decisions were no longer handed down from the highest editorial echelons and were instead made by consensus.

Interestingly, Stepp and others complained that the movement towards civic or public journalism felt forced and that many of the stories lacked interest and zest. Some stories seemed to pander to public interest. Furthermore, Adam Moss, the editor of The New York Times Magazine, lamented that new writers of the time lacked ambition and a sense of innovation—they needed to be told what to write.

By the mid-2000s, the Internet changed newsrooms once again. Online newsrooms started to merge with print newsrooms, and news was kicked out twenty-four hours a day. Major newsrooms also started dedicating space to television and multimedia studios. The highly technical aspects of reporting became an opportunity for journalists from Generation X and Generation Y (millennials) to prove their mettle. (Many of these younger journalists are “digital natives,” which means they came of age when the Internet was in wide use and grew up using the Internet.) Many newspapers started producing news for the Internet and updating and analyzing the news in print.

Changes in newsrooms coincided with changes in the way news was reported. Self-publishing software made it easy for anybody to report news; consequently, we entered the age of citizen journalism. In 2000, Oh Yeon-ho, a media entrepreneur from South Korea, claimed that “every citizen is a reporter.” Yeon-ho helped start the website OhmyNews, a crowd-sourced news site that by 2007 boasted fifty-thousand contributors from one hundred countries.

The rise of citizen journalists has proved appealing in times of turbulence. For example, in 2009, Iranian citizen journalists, who were engaged in protests following the presidential reelection of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, took to the Internet to report news. Similarly, in 2010 and 2011, citizen journalism played a key role in the Arab Spring and helped unseat Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi.

Currently, a notable outgrowth of citizen journalism is “stunt” or “reality” journalism, most notably practiced by VICE Media, a Brooklyn-based company. Representatives from VICE are careful to avoid labeling themselves journalists. Instead they intend to stage newsworthy events in places that other media organizations are unlikely to visit and document the outcomes. VICE has documented civil war (and cannibalism) in Liberia, shopped for bombs in Bulgaria, and in 2013 set up a basketball exhibition game in North Korea featuring Dennis Rodman and attended by Kim-Jong un, the leader of North Korea. Furthermore, VICE has partnered with old media powerhouses including CNN and HBO. Though representatives from VICE don’t claim to be journalists, they do disseminate information and to some extent interpret it. For example, after their “basketball diplomacy” stunt, VICE co-founder Shane Smith called for more “dialogue” between the United States and North Korea and claimed that fifty years of attempted diplomacy between the two countries has “failed.”

Citizen journalists represent what author Clay Shirky calls the “former audience.” These are audience members who transitioned into journalists. For readers, the rise of citizen journalism offers several advantages. News that is disseminated by citizen journalists is available as it happens and reflects the accounts of participants and other interested parties. Citizen journalism also allows the reader insights into news occurring in areas where the news is normally censored. Furthermore, the news and commentary spread by citizens is free. (It should be noted that even though this news is free, it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s of poor quality or unverifiable. Many pieces at The Huffington Post, a highly regarded website that provides views on politics and current affairs, come from unpaid writers who are experts in their fields. The Huffington Post has helped facilitate popular citizen journalism campaigns such as OffTheBus.) The appeal of citizen journalism has won many admirers, including Jay Rosen, a prominent media critic who runs the website Pressthink, and Howard Fineman, editorial director at the AOL-Huffington Post Media Group.

Of this new breed of journalist, author Alissa Quart writes, “One need not be elite, expert, or trained; one must simply produce punchy intellectual property that is in conversation with groups of other citizens. Found Media-ites [“Found Media” is a term Quart uses which includes citizen journalists] don’t tend to go to editors for approval, but rather to their readers and to their blog community. In many ways, they disdain the old models, particularly newspapers. …”

Marc Cooper, director of digital news at USC Annenberg, points out that sometimes citizen journalists report news better than their professional counterparts: “Journalism is now a mix of professional and amateur. Sometimes the amateurs are much better than the professionals, and it’s true in poker, too. There are professional poker players, and there are amateur poker players, and sometimes the amateurs kick your ass. Journalism is about storytelling. … There’s a lot of natural storytellers out there … and there’s a boatload of journalism students who get master’s degrees and still can’t tell stories.”

In more philosophical terms, journalism has evolved toward the citizen journalist; citizen journalism is an undeniable attractor that inevitably became popular when technology allowed the audience to create and share news. As pointed out in the book Blog!: How the Newest Media Revolution Is Changing Politics, Business, and Culture, people have always been interested in expressing themselves and understanding what other citizens have had to say, whether it be in the form of cave drawings, colonial pamphlets, or nineteenth-century journals. Nearly fifty years ago, philosopher Jürgen Habermas envisioned a public sphere where democracy would flourish and people would engage in conversation, argument, and debate.

Historically, access to citizen input has been limited by the media machine, which has allowed only journalists to write for the public, with occasional input from the audience in the form of letters to the editor, reader feedback, or “voice of the reader“-type articles. (The Poynter Institute’s EyeTrack studies suggest that such articles are among the most attractive to readers.) Nowadays, however, anybody with a basic understanding of journalism and a smartphone loaded with the necessary apps can produce compelling and engaging news.

Blaming citizen journalism for the downfall of modern journalism is like blaming biology for the evolution of eyesight. Much like citizen journalism, the development of visual organs is an undeniable attractor. Organisms of nearly every species have evolved eyesight independently because processing visual information is an efficient way to access information.

After speaking with dozens of experts and doing much research, I doubt that citizen journalism will undo the work of good professional journalists. Instead I think it will probably complement such work. Just as the development of radio, television, cable, and the Internet hasn’t stopped people from reading printed material, news spread by citizen journalists won’t take the place of work done by professional journalists. Most likely, people will treat citizen journalism as another taste available to their palates. For example, the next time an uprising occurs somewhere in the developing world, in addition to being able to follow the event on the radio, cable news, the AP wire, or some other professional news organization, people will also be able to read the work of citizen journalists on blogs and social-media sites.

The open spirit of crowd-sourced news and journalism will probably influence the bastions of traditional journalism in positive ways. “And perhaps,” writes Alissa Quart, “some of the conventions of traditional newspaper and magazine writing that can make it rigid and bland will fade into the background. Maybe some of the best qualities of the blogs—directness and informality—will positively infect us.”

The availability of free news and the rise of citizen journalism have threatened newspaper publishers, editors, and journalists. Nowadays engaging news that’s up-to-the-minute is freely available, and this fact, combined with decreasing advertising revenues and decreased trust of conventional media, has put newspapers on high alert.

It’s widely recognized that the newspaper business is in trouble. The late 2000s saw excellent general-interest publications, including the Rocky Mountain News and the print version of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, go defunct. The Tribune Company, which owns the Chicago Tribune and the Los Angeles Times, was hocked for $8.2 billion and left in the hands of Sam Zell and Randy Michaels. Not only do these men care little about journalism—Zell half-joked he’d like a “porn” section in newspapers—they also helped bankrupt the company and managed to infuse this venerable institution with an alienating and offensive work atmosphere.

Although newspapers still remain the largest employer in the media sector, with 223,600 employees in March 2012, the ranks of many newspapers are thinning quickly. Ad Age estimates that in 2012 newspapers were cutting an average of 1,400 jobs a month. (Internet media is adding four hundred jobs a month and is the second-largest employer in the media sector, with 113,100 people in November 2011.) Even “The Grey Lady” (The New York Times) has seen hard times. It cut one hundred jobs in 2009, and that same year advertising revenue was down 30 percent. Overall, the Pew Research Center estimates that the newspaper industry has diminished by 43 percent since 2000.

According to the Alliance for Audited Media, between March 2012 and March 2013, daily circulation for 593 U.S. newspapers that reported results dropped by 0.7 percent. Sunday circulation for 519 newspapers that reported results decreased by 1.4 percent. Newspapers that reported their daily circulation numbers could include digital editions such as “tablet or smartphone apps, PDF replicas, metered or restricted-access websites (“paywalls”), or e-reader editions.”

Some journalists and academics are predicting the imminent demise of newspapers. “Newspapers are going to be dead in the next few years because we don’t need them,” says Cooper. “We now have empowered ordinary people and experts and anybody who can get their hands on a smartphone … we have empowered them with the ability to publish and bring to us perspectives that we can accept or reject. … Thank God the monopoly on information has been broken. … Thank God we have a diversity of content that’s not controlled by a small group of priests that gets a stamp of approval from Poynter. … We don’t know yet what the new system or new order is … but we do know that the old order has been destroyed.”

Various experts suggest that in order to survive, most newspapers need to change in several ways. Based on my analysis, here’s a composite (and attributable) list of various suggestions:

By 2012, there were numerous examples of new media working with “old” or legacy media to distribute content and improve (digital) revenue models. Notably, Yahoo signed a content partnership with ABC News, and Facebook created partnerships with The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, and others. Nevertheless, according to the Pew Research Center, such efforts are limited, and “the news industry is not much closer to a new revenue model than a year earlier and has lost more ground to rivals in the technology industry.”

As we approached the second decade of the new millennium, many of these suggestions bore influence on publishers. More specifically, these suggestions point to digital publication and advertising as an answer to the problems newspapers are facing, and many publishers were eager to seize on digital dissemination as a panacea for their ailments. For example, The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and The Washington Post have developed pay models for digital readers. Additionally, in 2011, The Guardian, a leading British newspaper, started a U.S.-based, digital-focused newsroom. Finally, The Washington Post has developed some experimental news products, including Trove, a recommendation engine, and a social reader for Facebook. Of note, these companies have also invested heavily in mobile apps, online video, and Kindle Singles, which are works of long-form journalism sold through Amazon.

Such efforts to move toward digital dissemination have been met with some success. According to the Alliance for Audited Media, in March 2013 digital editions accounted for 19.3 percent of newspaper daily circulation, an increase from 14.2 percent in March 2012.

It should be mentioned that when it comes to virtual news consumption, legacy media publications aren’t the only game in town. Internet start-ups, including Digg, Flipboard, Pocket, and Feedly, have also tried their hands at the dissemination of news on the Internet. They have been experimenting with news aggregation, article recommendation, and bookmarking articles.

Many publishers, however, have realized that this digital bias may not be the answer to decreasing revenues, especially when it comes at the expense of daily print editions. For example, The Daily, a mobile app for the iPad published by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, shut down after two years. More significantly, in 2012 The Times-Picayune of New Orleans decided to focus on its website NOLA.com and produce a print edition only three days a week. This decision enraged residents of New Orleans and soon backfired. In light of lost advertising revenue, by May 2013 The Times-Picayune once again began publishing a daily newspaper.

Regarding this haphazard turn of events, David Carr, a media columnist at The New York Times, writes, “The industry tried chasing clicks for a while to win back fleeing advertisers, decided it was a fool’s errand, and is now turning to customers for revenue. … Newspapers that have cut their operations beyond usefulness or quit delivering a daily print presence have suffered. The audience has to be earned every day. Newspaper publishing will never return to the 30 percent plus margins it once had, but some people believe there is a business model. Warren E. Buffett thinks that a 10 percent return is reasonable, now that sale prices have sunk.”

Another problem with newspapers expanding their digital presence is cost. With declining revenue and circulation, many papers have struggled to pay for digital innovation while producing a daily news product that reflected their publication’s fundamental values.

Ultimately, despite all such pontification, there currently exists no clear path for newspapers. We just have to wait and see how (and whether) newspapers find their way out of the financial quagmire that they all seem to be stuck in.

It used to be that many newspapers were large, publicly held companies. But with plummeting circulations and valuations, newspapers are no longer great investment opportunities, and some big newspapers are being sold to private investors. For example, in 1993, daily circulation at The Washington Post peaked at 832,332. By March 2013, circulation had dropped to a little more than half at 474,767. Consequently, in August 2013, the cash-strapped Post and many of its sister publications were sold to Jeffrey P. Bezos, the founder of Amazon, for $250 million—a price that would have been considered unfathomably low just a few years before. Similarly, in August 2013, The New York Times Company sold its New England Media Group, which includes The Boston Globe, for $70 million to a group of local investors—a sliver of the $1.1 billion the Times company bought The Globe for in 1993.

Although Bezos is a genius who revolutionized how people consume goods, he has no background in newspapers; thus his possible plans for the newspaper are rife for speculation.

Jenna Wortham and Amy O’Leary from The New York Times write, “No baggage—and deep pockets—means room to try new things. Might Mr. Bezos apply tech industry concepts like frictionless payments, e-commerce integration, recommendation engines, data analytics, or improved concepts for mobile reading?”

Wortham and O’Leary go on to write that when it comes to establishing relevance in a digital marketplace, “That is an area where Mr. Bezos might be primed to flex his expertise in analyzing data to find ways to engage a younger audience. In addition, Mr. Bezos’s money could come in handy when it comes to adding to the newspaper developers, engineers, designers and others who could radically change the way the organization looks and runs.”

If the past is any indication of future success at The Post, the culture and commerce of technology from which Bezos emerged has proven engaging and relevant among digital audiences. For example, Facebook, Google, and Twitter have defined online diversion among countless Internet users.

Without a doubt, if newspapers went extinct, they would leave a void. A quick search of any news website such as Newser or Gawker proves just how influential big newspapers are. The news aggregated on these websites comes from publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal. Without these big publications, there would be no “free” news. Additionally, some argue that big newspaper publications adhere to principles and standards and that upstart websites have no obligation to adhere to journalism standards celebrated by their legacy-media counterparts. For example, WikiLeaks, which in all fairness is more activism than journalism, has been criticized for indiscriminately dumping anything on the Internet with little concern for the national security of the United States and its allies.

If newspapers were to disappear, the loss would also be felt at the level of civic journalism that focuses on the local news, issues, and concerns of specific communities. According to the Pew Research Center, “The civic implications of the decline in newspapers are also becoming clearer. More evidence emerged that newspapers (whether accessed in print or digitally) are the primary source people turn to for news about government and civic affairs. If these operations continue to shrivel or disappear, it is unclear where, or whether, that information would be reported.”

If there has been a silver lining for the news industry, and more specifically newspapers, it’s that in 2012 people increasingly immersed themselves in the news—even if by digital means. Thus there’s still a hunger for the news, which means that if newspapers and other legacy organizations figure out how to better tap this growing interest, there may be hope. According to the Pew Research Center, “Mobile devices are adding to people’s news consumption, strengthening the lure of traditional news brands and providing a boost to long-form journalism. Eight in ten who get news on smartphones or tablets, for instance, get news on conventional computers as well. People are taking advantage, in other words, of having easier access to news throughout the day—in their pocket, on their desks, and in their laps.”

Worries about the fate of the printed word on newspaper broadsheet can be extended to the fate of all types of print journalism. Although there’s no reason to make the foregone conclusion that audience attention is a zero-sum game and time spent surfing the Internet comes at the direct expense of print media, it’s interesting to wonder whether, in the future, all printed media could be replaced by digital media. When I asked technology journalist and Contently co-founder Shane Snow for his opinion on the matter, he offered me a detailed answer that hinted at the future of journalism.

“I don’t think that print will completely go away because there’s still an appetite for it,” says Snow. “Anything that’s working in print or online is getting niche or more targeted. … Article writing for general interest is getting tougher and tougher—article writing for ‘just the facts ma’am’ news. There’s this crazy technology that can have a machine write these human readable articles. Some of that is going to be replacing breaking news and crowd-reporting stories and Twitter-breaking news. The writers who are now doing that sort of work are going to shift to interviews in profiles that the robots and the crowd [can’t do,] which in the long run is positive. … We can get more interesting insight. … It takes humans doing research and talking to people to distill rather than the crowd coming together or machines analyzing data. I think that’s a trend we’ll see.

“Feature content and entertainment, the whole lifestyle, sports [and so forth] are going to be fueled by a different economic engine … in a lot of cases crowd funding … people buying individual stories or brand sponsorship. I would predict, based on the science that we’re seeing, that there will be a lot less crappy content out there on the Web because it won’t be economically viable … because computers and social media can leapfrog the bad stuff and get to the good stuff. There will be more of a market for more thoughtful content in the future.”

Aside from their physical characteristics, magazines have classically differed from newspapers in several ways. Some main differences between newspapers and magazines include tempo, function, and format.

Newspapers are often published daily, and the news carries immediacy. Magazines are printed as periodicals, and to a larger extent, their content is meant to be more evergreen. For example, when you’re waiting at the dentist’s office, you’ll likely be given the choice of reading several magazines, many of which are several months old. Despite their older age, these magazines will appeal to many readers who would hardly notice their age because more than likely a Q&A with Oprah Winfrey will still be interesting a year after it was written.

The history of magazines also differs from the history of newspapers. The first American magazines could be considered “periodicals of amusement,” as they printed uplifting and entertaining content. Additionally, in colonial America, the first magazines were pretty expensive and intended for a wealthy audience. Before 1800, around one hundred magazines were published in America, with the first being Andrew Bradford’s American Magazine and Benjamin Franklin’s General Magazine, both published in 1741. (Neither magazine lasted long.)

By the 1830s, magazines became less expensive and more affordable to the more general public. (Much like a penny was to be an attractive price for newspaper publishers of the era, a dime was the magic price for many early magazine readers. And because inflation didn’t become an issue until the United States was taken off the gold standard in the 1940s, a penny or dime retained much of its same buying power for several decades.) These magazines focused on general amusement, improvement, enlightenment, and family issues.

By the 1880s, the emergence of “dime novels” and “pulp” magazines made magazines more affordable to mass audiences. These publications were shoddily constructed and took advantage of technological advances, including the creation of paper from wood pulp and improved mechanization of the printing process. Many of the stories in these publications dealt with adventure and science fiction thus capturing the imaginations of young boys. For example, however ersatz, Luis Senarens’ Frank Reade, Jr., and His Steam Wonder (1884) drew from the work of Jules Verne. In general, the stories contained in such publications were poorly written and reductive. Furthermore, the content was often in poor taste and racist.

Shortly after the Civil War, the magazine business boomed in the United States—in large part due to the general expansion of the United States and favorable postage rates. Magazines of this era included Harper’s, McClure’s Magazine, and Cosmopolitan.

In the years following the Civil War, women’s magazines became increasingly popular. Some of these magazines were staffed by women. For example, Godey’s Lady’s Book, which was first published in Philadelphia in 1830, employed 150 women to tint the fashion plates. Ladies’ Home Journal was initially edited by Louisa Knapp Curtis, the publisher’s wife. Ladies’ Home Journal distinguished itself from other women’s magazines by concentrating on serious issues geared towards its women readers. This foresight was rewarded, and its circulation soon reached a whopping 400,000. Another women’s magazine of the era that broke new ground was Good Housekeeping, which was published in 1885 and presented a forum for consumer goods of the early twentieth century.

In addition to women’s magazines, many literary and scientific magazines rose to prominence in the years following the Civil War. At the time, literary was a broad term that encompassed political, literary, and artistic content. Many of these magazines endure to this day, including the magazines eventually known as Harper’s Magazine and The Atlantic Monthly, which from the beginning were of high quality and featured work by the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and famous British novelists. Additionally, Scientific American, National Geographic Magazine, and Popular Science were all founded before 1900.

Many early magazines prided themselves on their literary value and wouldn’t include advertising in their pages. Most notably, Reader’s Digest proved particularly recalcitrant and resisted the pull of advertising money until 1955. By 1900, it became apparent that advertising meant big money for magazine publishers. For example, Cyrus Curtis, the publisher of Ladies’ Home Journal, purchased the ailing Saturday Evening Post for $1,000 in 1897, and by 1922 this magazine was making $28 million a year. By 1947, 65 percent of magazine content was devoted to advertising.

Advertising had varied influence on the content of magazines. On one hand, early advertising advanced the visual appeal of magazines, made them more colorful, and improved the design. On the other hand, some magazine publishers were forced to grapple with a problem that still persists: editorial independence. For instance, in 1940, Esquire lost a piano advertiser after printing an article that recommended the guitar as a form of musical accompaniment. Other magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post, Time, and The New Yorker were pretty good at constructing a wall between advertising and content and making sure that advertising was “minimally offensive.”

Women’s magazines proved to be a preferred target for advertisers especially because, at the time, many women were the shoppers for their families. Advertisers were particularly drawn to magazines such as Better Homes and Gardens, which was first published in 1922 and printed the first service articles intended for homemakers. Interestingly, many women’s magazines of the early to mid-1900s, including Family Circle and Woman’s Day, were so intrinsically tied to advertising that they began as house organs for supermarkets.

One magazine that deserves special mention is Reader’s Digest, which was founded by DeWitt Wallace in 1922. From the beginning, Reader’s Digest distinguished itself by providing content that was condensed and derived from articles in other magazines. (With its condensed and derivative content, Reader’s Digest could be called the Internet of its day.) It wasn’t until 1933 that Reader’s Digest started to publish its own original content, and, in an unusual reversal, would often sell longer pieces to other magazines in return for the rights to publish truncated versions. The editors at Reader’s Digest were particularly interested in evergreen pieces and hoped their articles would have a shelf life of a year or longer. They demanded that their articles exhibit three cardinal characteristics: applicability, lasting interest, and constructiveness.

Using the nom de plum Lipstick, Lois Long electrified the pages of The New Yorker with her liberated and prurient prose. Her voice was prescient and could very easily find a welcome home today either in a print publication or on the Internet. In both her writing and life, Long flouted social and sexual mores and epitomized the 1920s flapper. She’d spend long nights drinking and dancing in speakeasies and would make her way into the office of The New Yorker in the wee hours of the night ready to write. Her readers loved her writing and so did Harold Ross, the first editor of The New Yorker and a prim and proper Midwesterner.

In the last three decades of the twentieth century, concerns about decreasing magazine readership—in particular younger readers—influenced the design and budget of many magazines. Between 1986 and 2002, the number of newsweekly readers aged thirty-five and below dropped from 44 to 28 percent. Moreover, the share of young long-form readers dropped from 39 to 20 percent.

In an article titled “Does Size Matter?” author Michael Scherer does a good job of explaining how magazines evolved during this period.

No one can deny the visual sea change that has overtaken the magazine industry in the last three decades. Most magazines now resemble movie posters more closely than they do the dry pages of a book. They are filled with color, oversized headlines, graphics, photos, and pull quotes. The gray text page, once a magazine staple, has been all but banished by a new breed of art directors who have gradually made their way up the masthead.

At Rolling Stone, once an exemplar of long-form journalism, shorter articles and reviews supplanted longer features. The intention was for the reader to string together articles of interest to create their own narrative rather than depend on the narrative of a long piece. Increased choices in the media marketplace had made the reader more savvy and no longer dependent on singular authors to establish a point of view. Even magazines such as Playboy that still touted long-form journalism did their best to insert numerous access points into articles in order to attract readers.

It should be noted that despite what some people have claimed, there was no hard-core evidence that readers had become stressed for time, “attention-deficit,” and averse to longer articles. During this time, interest in reading books was still strong, and between 1996 and 2002, the amount of time the average reader spent with all media increased by 45 minutes a day. It’s just that with the emergence of the Internet and proliferation of cable television, audience members had more choices and became better informed.

Let’s fast-forward to the magazines of today. Much like newspapers, magazines are figuring out how to straddle the divide between “Old Media” and “New Media.” Although magazines have fared better than newspapers, they are dealing with many of their own issues. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the size of the magazine industry fell 29 percent, from 156,212 in March 2002 to 111,126 in March 2012. Furthermore, there was a 13.3 percent drop in the number of establishments publishing periodicals, from a high of 9,232 in 2007 to 8,003 in 2012.

“There is mixed information out there about the state of the magazine industry,” says Dr. David E. Sumner, professor of journalism at Ball State University. “Some sources I read say that overall magazine revenue is climbing slowly due to growth in digital ad revenue. Print circulation appears to be holding its own, especially among travel, epicurean, hobby, and leisure interest, and magazines aimed at affluent readers.”

According to the Alliance for Audited Media, from the first half of 2012 to the first half of 2013, among the 390 consumer magazines that reported results, paid and verified circulation decreased by about 1 percent, single-copy sales decreased by about 10 percent, and paid subscriptions decreased by 0.1 percent.

In addition to conventional print format, many magazines have decided to take their publications online. (Some, like Newsweek, which merged with The Daily Beast, have decided to go exclusively online.) Publications such as The New Yorker and Vogue have digitized their archives and sold parts of them online. According to the Alliance for Audited Media, from the first half of 2012 to the first half of 2013, the number of digital editions increased from 1.7 percent of total circulation to 3.3 percent or 10.2 million copies.

But how are these magazines faring on the Internet? According to a 2010 study (survey) titled “Magazines and Their Websites” done by the Columbia Journalism Review, the answer is not well.

Although those involved with magazines and websites have varying levels of knowledge and sophistication about their métier, it’s fair to say that the proprietors of these sites don’t, for the most part, know what one another is doing, that there are generally no accepted standards or practices, that each website is making it up as it goes along, that it is like the wild west out there.

To its credit, the study does a good job of suggesting how to improve the online presence of many magazines. First, magazines should devote staffs to online-only efforts instead of having print journalists shoulder both duties. Second, in light of the fact that the online components of many magazines meet less rigorous fact-checking and copyediting standards, institutional organizations such as the American Society of Magazine Editors, Magazine Publishers of America, and Online Publishers Association should come up with standardized guidelines and codes of conduct. Third, instead of concentrating on “paywalls” or paid online subscriptions, magazine publishers should concentrate on revenue generated from online advertising. Fourth, the content provided on these sites should incorporate more aspects of multimedia. Fifth, instead of relying on editorial decisions, privilege, and whim, online magazine content should be dictated by online traffic. Furthermore, more thought should go into cultivating the website’s identity and argot. Simply dumping content from the print magazine onto the website may be a bad idea.

In his book Here Comes Everybody, Clay Shirky recounts how the introduction of the printing press in the fifteenth century didn’t immediately improve the world. In fact, this revolutionary introduction was followed by years of confusion that wasn’t resolved until well into the Renaissance. During these years, printers battled it out with scribes who once held a monopoly on the printed word. Similarly, the Internet is a relatively new invention. To expect that within a few years magazines and newspapers can effectively organize, change, and succeed is chimerical thinking.

Although publishing is no longer governed by economic or managerial concerns, a fact that puts print magazines and newspapers at a competitive disadvantage, print publishers still possess one main advantage. Large print publishers are complex organizations that have much experience disseminating swathes of information on an emergent basis. Such expertise lies outside the purview of most citizen journalists or smaller publication efforts and can serve as a foundation for future efforts.