Good writers spend about 80 percent of their time doing research and 20 percent of their time actually writing. Obviously, doing research is important and has wide-ranging benefits that touch on every aspect of your final product: the article. Good research helps you determine who to interview, what questions to ask, what’s important with respect to the issue being explored, and much more.

Margaret Guroff, features editor at AARP The Magazine,1 states, “The key to writing engaging features is doing a ton of research so that you have the details at your fingertips … so that you really understand your subject and are speaking from a place of authority.” Although Guroff is specifically talking about features, her advice holds with all types of stories.

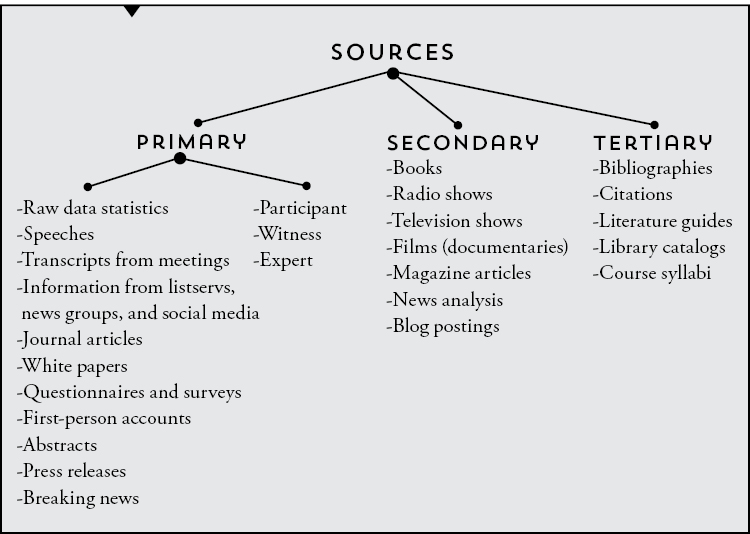

Research resources can be divided into primary sources, secondary sources, and tertiary sources. In journalism, primary sources can be either written documents or people who you are interviewing. (For more information on human sources, flip to Chapter 5.) Primary sources are unfiltered and haven’t been interpreted by a third party. If they’ve been analyzed at all, the person or group doing the analysis is the person or group who did the research. Examples of primary sources include raw data, statistics, speeches, transcripts from meetings, listservs, newsgroups, questionnaires, first-person accounts, newspaper articles, and some scholarly journal articles published by researchers. Secondary sources are one step displaced from the original data. They analyze, critique, summarize, interpret, and so forth. (In other words, secondary sources normally deal with higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a pedagogy that helps explain how we incorporate and use acquired knowledge. For a more detailed description of Bloom’s Taxonomy, see Chapter 8.) Examples include television shows, radio shows, documentaries, books, news analyses, and magazine articles. Tertiary sources refer to course syllabi, bibliographies, citations, literature guides, and library catalogs.

When writing an article, it’s often a good idea to balance your use of primary and secondary sources. Primary sources such as journal articles provide plenty of good information, especially when writing about science. Secondary sources can help you interpret an issue and explore alternative avenues. It should be noted, however, that secondary sources have their limitations. Most important, you must be careful when directly quoting or requoting from a secondary source because with every round of ensuing use, passed-down information risks misinterpretation. In fact, certain publications like Reader’s Digest and Men’s Health won’t allow their writers to use quotations from secondary sources.

Using information from a secondary source can be compared to playing a game of “telephone.” In telephone, one person comes up with a word and whispers this word to another person. This person then whispers the word to another person, who whispers it to the next person down the line, and so on. By the time the word gets to the last person, it is never the same word it was at the beginning of the game. More generally, with each round of transmission, the meaning of information can change.

Sometimes the only way you can get the information that you need is by turning to secondary sources. For example, if you have limited access to a celebrity or important person and you need to put information about this person in your article, referring to a secondary source such as an already-published profile may be prudent. When using information from a secondary source, be sure to cite the publication or source and consider paraphrasing the information instead of directly quoting it. If you have the opportunity, it’s always better to gather information from a primary source rather than a secondary one.

When doing research for an article, there are several places you can turn to for information.

Databases are great because you can search them using key terms, subject headlines, and search parameters. Plenty of institutions, universities, and public libraries pay for subscriptions to large databases that serve as aggregators for primary- and secondary-source information. If you don’t have formal university access to databases, you can usually access many databases by visiting a public, college, or university library.

Some popular databases include LexisNexis, which offers access to news, congressional information, and more; Google Scholar, which is a vast searchable database that provides access to tons of scholarly and journal articles; Web of Science, which is a multidisciplinary database that covers science, social science, and more; PubMed, the definitive medical database, which accesses MEDLINE; and (the interdisciplinary) Academic Search Premier, which provides access to 8,500 journals, many of which are full text.

People sometimes forget that a big library can’t be beat when it comes to printed books, journals, magazines, and so forth. However surprising this may sound, there’s still much information that exists only in printed form and is not available on the Internet. Libraries have searchable digital catalogs that track down printed resources in the library, and if a library doesn’t have the book you need, you can usually get a copy through interlibrary loan. Older newspaper collections are also available on microfilm. In addition to offering access to printed materials, libraries also employ librarians whose job it is to help library patrons. Librarians are founts of knowledge who are happy to spend time with you and help with your research.

One unfortunate limitation of most printed materials is that they are less timely than Internet resources. Because it often takes months or years for most printed materials to be published, the information they contain can become outdated while the manuscript is in development or with the publisher. In contrast, information on a website can be updated in minutes, hours, or days.

Some useful written materials to consider when researching an article include nonfiction works, textbooks, bound dissertations, and even children’s books. In fact, a children’s book can serve as a valuable introduction to topics that are new to you.

Reference works can be a great way to introduce yourself to a subject and gather basic facts. For example, the Encyclopaedia Britannica has an online counterpart that can be accessed for a small fee or for free through the library. Other useful reference works include dictionaries that cover specific topics such as Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary and Stedman’s Medical Dictionary.

If you’re interested in learning more about a specific person, you can search the Marquis Who’s Who series or the near-monthly magazine American Biography. American Biography offers lively 2,500-word profiles replete with statistics and bibliographies.

Wikipedia is also a good place to get some ideas about an issue before you start research in earnest. If you were to use any information from Wikipedia, you would need to independently verify it before it goes into your article. Because anybody can access and edit the website, Wikipedia entries can be biased and wrong. Fortunately, many Wikipedia entries are followed by detailed references that will point you toward sources that can be scrutinized more closely.

“As much as I admire the massive accomplishment that Wikipedia has achieved,” says Dr. Robert J. Thompson, professor of television and popular culture at Syracuse University, “Wikipedia is not the way to do research. … It’s the way to solve bets, but it’s not a way to do research.”

Websites provide information on a variety of topics. When deciding whether to use information found on a website, it’s important to use good judgment and evaluate the source. Never assume that information found on a website is correct, and always use information on a website in conjunction with other sources. Here is a list of questions to consider when vetting a website’s authenticity:

Many universities, institutions, medical centers, corporations, chambers of commerce, associations, advocacy groups, and so forth go to great lengths to provide useful information to the public. Such entities often have public-relations departments that field media requests and are more than happy to send along fact sheets, pamphlets, articles, brochures, annual reports, and more. Remember that you’re not inconveniencing these groups by asking for their help. In fact, you’re probably helping their cause by focusing on an issue that’s important to them.

A quick Google search will likely help you find an organization or institution of interest. Once you find this entity of interest, navigate to its website and search for the information that you need. Other more specific depositories of information include the Encyclopedia of Associations and the website GuideStar, which offers background on nonprofits and charities.

Sometimes you must be careful when dealing with materials that originate from an institution or organization because they may represent a specific interest. Press releases often originate from entities with commercial, social, or political interests, so they must be carefully considered before you use any of their information. Even press releases from reputable sources, including PR Newswire and EurekAlert!, which is sponsored by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, must be carefully scrutinized.

That said, press releases can be wonderful resources, and it may behoove you to e-mail the public-relations department at an organization or institution and ask to be put on a recipient list for up-to-date press releases—especially if such press releases represent a “beat” that you report on. For example, the Association of American Medical Colleges routinely sends out press releases to interested parties, including reporters who cover medical education.

In addition to collecting taxes, the U.S. government provides all types of valuable services, including resources for research. If you’re interested in primary sources, such as congressional transcripts, visit www.senate.gov or www.house.gov. If you want statistics for a trend piece or other type of article, try visiting www.fedstats.gov.

Various government agencies also make information freely available through education and public-outreach programs, including NASA, National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institutes of Health (NIH), FDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

Never underestimate the knowledge interested members of the public can provide. This information can be attained from both listservs and newsgroups.

Listservs are electronic newsletters whose audience consists of readers who are interested in a specific topic. You must subscribe to these listservs, and after subscribing, postings are sent to your e-mail account on file. These listservs are fueled by participation from audience members. There are countless listservs in the ether of the Internet. I once subscribed to a particularly active listserv hosted by the American Medical Writers Association, and after a few days, I asked to be pulled off the list because the number of e-mails I received was overwhelming.

Newsgroups are modern-day bulletin boards that anyone can freely access. Like listservs, there are countless newsgroups out there, and many can be accessed through Google Groups.

You can monitor the Web and receive updated news on a topic in your e-mail inbox through Google Alerts.

Conferences can be excellent places to access new stories and emerging research. Conferences allow a journalist to interact with experts in the field and to network with other journalists. For example, every year the American Association for the Advancement of Science hosts an annual meeting that draws thousands of scientists, engineers, students, and journalists from all corners of the planet.

One roadblock that you may encounter while gathering information at a conference is something called an “embargo.” Embargoes are placed by prestigious academic journals that plan to publish the research of conference presenters at some future date. Embargoes bar other publications from writing about the research until the publication date has arrived. The vast majority of publications respect embargoes and don’t violate them. One unfortunate effect of embargoes is that presenters are often reluctant to discuss their work with journalists present for fear of violating the embargo and losing a chance to be published in a prestigious journal.

Interestingly, the “embargo” concept has extended past scientific research. For example, journalists who evaluate video games for a living often receive advance copies of a video game but are asked not to release their reviews until its release date. Disparaging reviews before a game’s release would be bad for sales.

In December 2009, The Seattle Times engaged in a social-media experiment of sorts. Using Google Wave (which has subsequently shut down) and Twitter to engage the audience, they tracked someone suspected of slaying four police officers.

According to an article in The Seattle Times, “Some elements of the Wave included links to police scanner audio, live video, information about road closures, school lockdowns, suspect information, and more. A manhunt map was created inside the Wave and updated by participants. And a map was linked inside the Wave that seattletimes.com then used on the site. It was useful to producers updating the site because they could put information out and get tips back instantly. We then could pass the tips on to the Metro desk and follow along that way. It was like using Twitter with a real-time response and rich content.”

This “experiment” hints at the potential for social media to expand a journalist’s ability to research and find sources for a story. Sometimes receiving useful information, finding human sources, or even generating story ideas is as easy as requesting help and crowdsourcing concerns and questions. Here are some outlets to consider when using social media to research a story:

In the wake of the Boston Marathon bombings in April 2013, Reddit was thrust into the limelight when Redditers started scanning pictures from the scene in order to identify possible perpetrators. Their theories mushroomed into a virtual witch-hunt for which Reddit subsequently apologized. This crowdsourcing analysis was rife with speculation, and several innocent people were unfairly accused.

Keep in mind that although social-media sites can be used for research and gathering news, they aren’t necessarily news sites. The objectives of many social-media sites differ from the objectives of news organizations. Furthermore, social-media users aren’t necessarily journalists or citizen journalists.

In an article titled “After Boston, Still Learning,” journalist Mónica Guzmán offers some sage advice on how journalists could help social media. “Understand and respect the breadth of platforms where people speak and the voices they speak with. Join them when you can. Most importantly, cultivate a culture of responsibility with everyone who shares information. That’s the lesson of the Boston manhunt. It’s what this new media world most needs today.”

Using social media for research has its limitations. First, you usually have no idea if the information is verifiable or transparent; consequently, you must be discerning. Second, people engaged in social media have no reason to reply to you or answer your questions. There’s no social-media etiquette, per se. Third, the world of social media is constantly changing, and there’s no guarantee that any social-media site will be up and running next year, next week, or even tomorrow. Some examples of social-media ventures that have folded or are on their last legs include Yahoo!, Buzz, Google Wave, Digg, Myspace, and Friendster. Fourth, jargon can be a big issue when using social media. For example, check out the sidebar below for commonly used Twitter abbreviations and symbols.

On a final note, spending time doing research and immersing yourself in a subject comes with tertiary benefits. For example, sometimes you do so much research for a story that you become a temporary expert or—on the rare occasion—a bona fide expert. The more research you do, the more knowledge you accrue. And remember, knowledge is a journalist’s best friend.

1 AARP The Magazine is the biggest magazine in the United States, with a circulation of nearly 22 million.