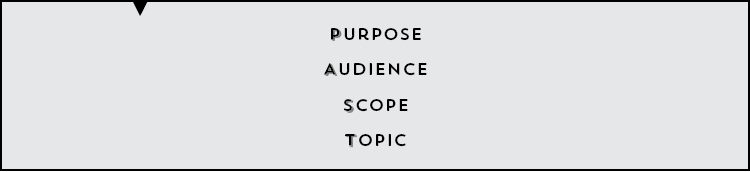

All documents share fundamental characteristics that should be considered before any writing takes place; in other words, every document has a PAST (purpose, audience, scope, and topic). (Medical writer Thomas A. Lang suggested a similar pedagogy; however, I switched out “setting” for “scope.”) First, every document has a purpose or goal, which should be fulfilled once the document is completed. For example, if you were to write a story on cosmetic surgery that’s intended for high school students, the purpose of the cosmetic-surgery story may be to warn high school students about its dangers. Second, every document has an audience or intended readership that you must carefully consider when writing the piece. With regard to the cosmetic-surgery piece, because the piece has an audience of high school students, you would best avoid using unexplained medical jargon or technical terms. Third, every document has a scope or breadth, and the document’s content should be focused to fill this scope. For instance, with the cosmetic-surgery story, the scope of the piece should focus on cosmetic surgery; there’s no reason to discuss neurosurgery unless the connection between cosmetic surgery and neurosurgery is clear and thematic. Finally, every piece speaks to some topic. Obviously, cosmetic surgery is a medical topic. (Some documents cover various subtopics—for example, the cosmetic-surgery piece could also examine psychology.)

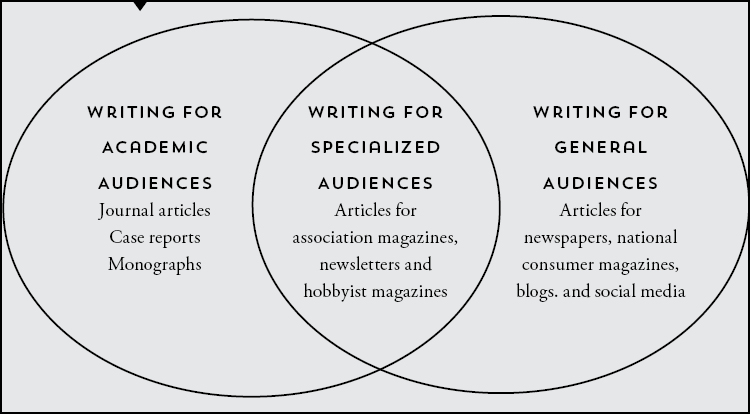

Articles are written differently for different audiences; consequently, it’s important that the author carefully considers the audience before any writing begins. With respect to your audience, you must consider the arguments you pose, the vocabulary you use, the allusions you make, the tone you adopt (snarky, cynical, casual, conversational, or academic), the message you present, and even sentence length. An article is tailored for the instruction and enjoyment of the typical member of your audience. For example, after analyzing your audience, you probably wouldn’t write an article about gun control in Highlights, a magazine intended for children.

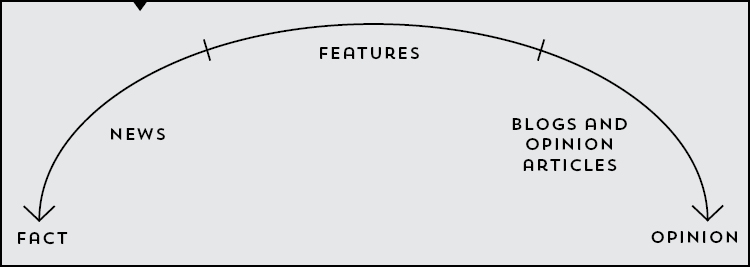

Most articles or stories written for general and specialized audiences fall into three categories: news, features, and opinion pieces. I’ve decided to expand this group to include blog postings, which, although similar to other types of articles, have their own distinct considerations.

Because characteristics of blog postings, news articles, feature articles, and opinion articles sometimes overlap, they can best be conceptualized on a continuum or spectrum. On one end of the spectrum you have news articles, which focus on facts. In the middle of the spectrum you have feature articles, which principally incorporate opinion (often expert), facts, and narrative or storytelling elements. At the far end of the spectrum, you find opinion pieces and blog postings, which often take the form of columns or commentaries. Blog postings and opinion pieces usually present opinion—either of the publication or the author—as of primary importance and use argument for support.

Features hold a special place in the hearts and minds of many journalists. They provide a breadth of creativity and form distinct from news and opinion pieces. “I find it to be the most satisfying form of writing there is,” says science journalist Robert Irion, “because you can become a temporary expert in this one field or subdiscipline. You get to bring your audience into this realm that they would never otherwise have access to. You are their portal into this other realm that they find fascinating. Through your own words, and through your experiences as a reporter, you’re revealing this world to them, and it’s a privilege to do that. … Feature writing is a lifelong pursuit. It’s one in which you continue to improve. Your work becomes deeper and richer over time.”

Traditionally, feature articles in print format have been associated with magazines, but over time, newspapers have embraced the feature article at the expense of the inverted pyramid. Although feature writing in magazines and newspapers has to a great extent converged, classically, features found in magazines differ from those found in newspapers in several ways. First, whereas features found in magazines are intended to have longer lives and be more “evergreen,” features found in newspapers are more likely to analyze issues of the day. Second, magazines will sometimes require that a feature be written with certain structural parameters in mind—an anecdotal lede, tight nut graph, and so forth—whereas newspapers are a bit more free flowing in the structure that their feature writers ascribe to. Third, features found in magazines can be longer, contain more sources, and are more thoroughly fact-checked than newspaper features, which are turned out on stricter deadlines. Finally, features written in newspapers are intended for a general audience whereas magazines often have their own specific audiences.