How should a person look?

Obviously there’s no right answer to this question. Other than sharing some common anatomical parts, all people look different. Some of us are short, tall, skinny, overweight, white, black, and so forth. We look as we look.

Similarly, the structure of an article—most typically a feature article—has no predetermined appearance. It takes on a shape that reflects its purpose, scope, audience, angle, publication, and more. After spending hours, months, or even years researching a piece, the article will reveal its shape to the writer. When this occurs, your relationship with the article is about to be consummated.

“The best stories,” writes Chip Scanlan of the Poynter Institute, “often create their own shape; writers consider their material, determine what they want the story to say, and then decide on the best way to say it.”

So why do we spend time characterizing the structure of an article? To be fair, many journalists and academics don’t spend much time discussing structure, believing that any preordained structure forced on a story will appear contrived. “I just write a story, and based on whatever comes out, I recognize the structure,” says Dr. David E. Sumner, professor of journalism at Ball State University. “Structures tend to be fluid and very nonscientific. I tend not to emphasize rigid structures, except the chronological narrative.”

I’ve decided to discuss structure first because I find it interesting, and, more important, the characteristics intrinsic to certain pedagogies of structure may direct you when considering what to concentrate on once your article starts to take shape. For example, if the shape of your article starts to look like the diamond structure—with the specific becoming more general, then the general becoming more specific—you may want to consciously conform to this structure.

Of note, some publications choose that their articles adhere to a certain structure. Typically, this structure is some variant of the nut-graph structure with an anecdotal lede, nut graph, and so forth. In these cases, a writer has less latitude when planning out a story. Furthermore, many award-winning stories have a novel structure that incorporates expert elements of storytelling, including nuanced flashbacks and fractured structures, two things that lie outside the scope of this text.

The narrative structure is probably the best appreciated of all structures used to write a feature article. It is written in a straightforward fashion, with a beginning, middle, and end.

Sara Quinn, a faculty member at the Poynter Institute, says of the narrative structure, “You’re led along and don’t know how it will end. In a lot of ways, that’s like a movie because it’s emotional, it has a lot of detail, and it makes you really feel something.”

Features written in the narrative structure are often told chronologically. Telling a story in chronological fashion has proven highly successful for many writers. Between 1979 and 2003, nineteen of twenty-five Pulitzer Prize-winning features used narrative (chronology) as either a main structure or combined with some other structure. (If you haven’t done so already, I highly suggest that you link to www.pulitzer.org to read some Pulitzer Prize-winning articles.)

Some stories are naturally suited for a narrative structure because they have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Let’s consider the story of the “Beltway Sniper” who in 2002 terrorized the residents of Washington, D.C., Virginia, and Maryland.

BEGINNING: In October 2002, an unidentified sniper—soon labeled the “Beltway Sniper”—started assassinating unsuspecting victims in Washington D.C., Virginia, and Maryland.

MIDDLE: Citizens of the Washington D.C. area started panicking, and the senseless shootings caught the attention of the nation and the world. Law enforcement spent a few tense weeks tracking down the killer or killers.

END: On October 24, 2002, John Allen Muhammad and his young accomplice, Lee Boyd Malvo, were finally caught. Muhammad was tried and executed by lethal injection. Malvo is serving consecutive life sentences with no possibility of parole.

Obviously, there’s much more to the story of the “Beltway Sniper,” but the unfolding events make for a good narrative structure. There’s a linear and clear-cut complication (a sniper or sniper team is on the loose) and a resolution (the perpetrators are caught).

Stories that use the nut-graph structure are also referred to as news or analytical features. This structure was developed at The Wall Street Journal and is widely used at this and other publications. This structure’s hallmarks include anecdotal leads that hook the reader’s attention, followed by alternating sections that amplify the story’s thesis and provide balance with evidence that presents a counterthesis. But its chief hallmark is the use of a context section, the “nut graph” in newsroom lingo.

With the nut-graph structure, a writer starts with an anecdotal lede that hooks the reader’s attention. The nut graph then presents a thesis. The body paragraphs expound on and support this thesis as well as expounding on and supporting any countertheses.

In a 2012 Los Angeles Times article titled “Dengue, Where Is Thy Sting?”, journalist Vincent Bevins uses the nut-graph structure to describe the release of genetically engineered mosquitoes to combat dengue fever. Bevins starts with an anecdote about researchers in Brazil releasing mosquitoes outside a family’s grocery store. The nut graph explains how the Brazilian government officials are releasing genetically engineered mosquitoes to kill off dengue-spreading mosquitoes.

The small, sun-scorched neighborhood of Itaberaba in this city in Bahia state is the leading testing ground for a controversial effort to combat dengue fever, the harrowing disease that kills 22,000 people a year worldwide. Scientists backed by the state government are releasing millions of the engineered mosquitoes into the wild with the goal of exterminating the species here—and, perhaps eventually, the entire country or world.

The body of the piece further explains dengue fever—a disease that causes symptoms ranging from flu-like to deadly hemorrhagic fever—and how biologists have engineered male mosquitoes to transfer deadly mutations to their offspring that will kill them off before they mature. The body also introduces the countertheses that some biologists and environmental groups oppose introducing mutated mosquitoes into the wild.

The nut-graph structure is very useful when reporting trends. First, an anecdotal lede illustrates the trend. Second, the nut graph explains the trend and introduces the countertrend. Third, body paragraphs explore and expound on the trend and countertrend.

Chip Scanlan used the nut-graph structure in a 1994 newspaper article titled “Too Young to Diet?” The lede in Scanlan’s story introduces Sarah, a ten-year-old dieter. The nut graph explains the dangers posed by childhood dieting, including the risk of developing eating disorders. It also explains how the countertrend, an obesity epidemic in children, has contributed to the dieting trend. The rest of the story examines both issues using facts and narrative.

Jon Franklin, who won the first-ever Pulitzer Prize for feature writing with “Mrs. Kelly’s Monster,” has thought a lot about this structure. In his book, Writing for Story, he draws comparisons between writing features and writing fictional short stories. He also compares feature writing to filmmaking.

According to Franklin’s organic structure, the fundamental narrative “molecule” of the feature article is the image; images are the smallest bits of a story. A set of images forms a focus, a larger chunk of copy that “focuses” on an action. Foci are linked together by transitions to form larger foci. These larger foci represent changes in time, mood, subject, and character.

Franklin also uses levels to characterize structure. First, there’s the polish level that deals with grammar, punctuation, imagery, and style. Second, there’s the structural level, which deals with the different foci and how they interconnect. Third, there’s the outline level, which is the most significant and deals with the interplay of characters and action.

Franklin notes that in a story, the first major focus is normally the complication, the second major focus is the (three-part) development, and the third major focus is the resolution. During development, the complication, including its past and present, is explored. The writer will also examine how the complication is being tackled and whether there has been a process of trial and error when tackling the complication. (More complicated narrative structures, such as flashbacks, often find a place in the development focus.)

William E. Blundell, author of The Art and Craft of Feature Writing, suggests a structural approach that has won many fans among professional journalists, including science writer Robert Irion. Irion teaches a method of writing features that’s inspired by Blundell’s work.

Here’s a breakdown of the six parts, which highlight questions that the writer may consider when addressing each part. Of note, not all stories consist of all six parts, and not all six parts need to be focused on equally.

“When I’m teaching magazine journalism,” says Irion, “I typically teach a rather standard story structure. It’s a canonical research narrative structure that any editor is happy to receive because … most readers will be able to make the most sense out of the story through this chronological retelling.

“You have your opening section, which has to be very grabby and make the reader want to invest the rest of their time in reading the entire piece—the first 400 to 500 words are so important in that respect.

“But then you want to … set up the context for the reader by describing what’s come before. This history section is something that you can re-create through your own research and by asking the scientists their views about the most important work that’s come before …

“And then you move to … an essential explanatory [section] in which you’re probably going to be relating some on-scene details. …

“Finally, you move on to implications. … What does this all mean? … Why is it important to society or to our knowledge of nature or the universe? What are some of the possible impacts and public policy [implications]? And, possibly, a ‘what’s next’ section. … What are the some of the main unanswered questions?”

The high-fives formula consists of five parts:

THE NEWS. What’s happening? The five Ws and one H.

THE CONTEXT. Does this issue or trend have a history? Explain the background.

THE SCOPE. Is a local issue part of a trend or national story?

THE EDGE. Where is this issue leading? What’s going to happen?

THE IMPACT. Why is this issue newsworthy? Who cares and why?

Many features embrace elements of the high-fives formula.

This structure proceeds from specific details to general ideas. It starts with a lede and nut graph, which are supported in the body of the article. Explanations also appear in the body. The conclusion ties back to the introduction.

This structure is reminiscent of several short features or book chapters linked together—each with a lede, body, and conclusion (kicker). The sections must flow well and engage the reader. Each new section begins with a list that summarizes key points.

When examining an institution or organization with discrete and separate functions, a writer can divide the story into parts describing these functions. For example, if you were examining the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates, an organization that certifies international medical graduates, you may divide a story to reflect three main functions of this organization: accreditation, acculturation (of international medical physicians), and philanthropic measures.

The diamond structure starts out with an anecdotal lede that illustrates what the issue or story is about. From the anecdote, the story then broadens to describe the issue. In the conclusion, the writer returns to the initial anecdote. This structure is figuratively described as a diamond because its scope goes from specific (narrow) to general (wide) and back to specific (narrow). Diamond-shaped features also have nut graphs. The diamond structure can be used to write a feature article, and it is commonly used in broadcast news and newspapers.

In the wake of the global financial crises, which began in 2007, many people lost their jobs. Unemployment became a big issue. Anecdotes about people unable to pay their bills and care for their kids were rampant. If you were to create a story about unemployment, you might consider a diamond structure that started and ended with a specific anecdote examining one person or family’s struggle with unemployment. In the middle of the article, you could then examine unemployment issues in a broader context, including economic, social, and political concerns. The conclusion could return to and expand on the original anecdote that examined an individual’s or family’s struggle with unemployment, thus narrowing and completing the diamond structure.

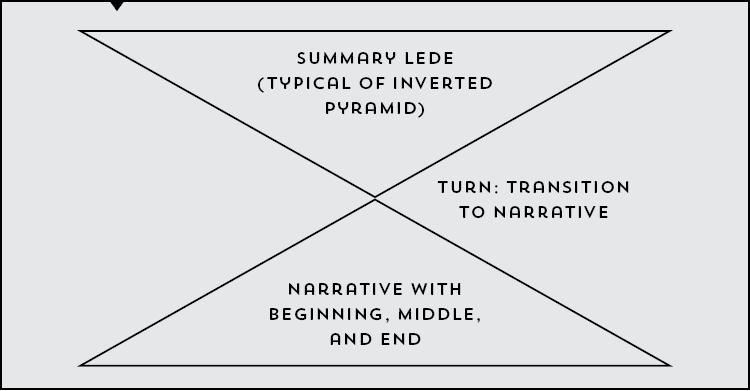

The term “hourglass structure” was coined in 1983 by Roy Peter Clark. It is a hybrid between the inverted pyramid structure and the expanding narrative. Although best suited for dramatic stories, it can be used to cover crime, government stories, economic issues, and more.

A story shaped with the hourglass structure in mind begins as any typical news story does: with a summary lede followed by a few paragraphs of detail in order of descending significance. The details deal with the most important aspects of the story: the five Ws and one H. In the middle of the piece, there’s a distinct “turn” or transition to narrative. This short turn shifts the focus by directly attributing the following narrative to an eyewitness, law-enforcement official, expert, character, victim, or so forth. The last part of the hourglass consists of a narrative with a distinct beginning, middle, and end.

The nice thing about the hourglass structure is that it caters to different types of readers. The beginning part, which resembles the inverted pyramid, appeals to the time-strapped reader who just wants the news. The expanding narrative appeals to the reader who wants to luxuriate in the details of the story.

The five-boxes structure was conceived by Pulitzer Prize winner Rick Bragg. Elements of this approach are apparent in his writing.

Here are the five boxes:

In his 1995 New York Times feature “Where Alabama Inmates Fade Into Old Age,” Bragg uses elements of the five-boxes approach to present the story. In the first box, Bragg introduces Grant Cooper, a convict and one-time murderer who is now with disability from a stroke and with dementia. The second box, or nut graph, presents the theme of the story: aging convicts serving life terms who need special and safe accommodations. The third box starts with the bucolic image of an Alabama prison that houses older prisoners with disability. After this new image is introduced, we learn more about how the entire prison population is graying and how they will need special medical care and facilities. The fourth box presents ancillary information about how these prisoners are no longer a risk to society and pitiful images of prisoners with a low quality of life. The kicker ends with the following quotation about how most of the prisoners die all but forgotten:

There will be nothing on the outside for him. Warden Berry said that when an inmate reached a certain point, it might be more humane to keep him in prison. Wives die, children stop coming to see him.

“We bury most of them ourselves, on state land,” he said. The undertaking and embalming class at nearby Jefferson State University prepares the bodies for burial for free, for the experience.

“They make ‘em up real nice,” the warden said.

The actual crafting of a feature piece is difficult for any writer. Whereas news pieces and opinion articles sometimes follow clear-cut formats—the inverted pyramid and essay respectively—feature articles can take various forms. This diversity of structure makes features particularly hard to construct, especially for a beginning writer. Different writers have their own idiosyncratic methods for constructing a feature piece, which make articulation of such methods even more difficult. Nevertheless, some general tips and approaches may prove useful.

Many writers like to stay organized when writing a feature story. They will pull relevant quotations from their sources and list them in one set of notes, and pull facts, figures, theoretical concepts, and so forth and list them in a second set of notes. By doing so, it becomes easy to refer back to this information as needed. Once all of their quotations and facts are organized, some writers begin a feature in a chronological fashion. They will write the lede, nut graph, body, and conclusion in that order. While writing each section of the story, the writer will consider narrative and structural elements, including images, background, details, conflict, resolution, and impact.

Crafting a story in systematic fashion can be challenging—especially for the new writer. Irion suggests a different method—one he used earlier in his career—which may be useful for those new to the field. It involves mapping out relevant quotations first and filling in details later.

“I’ll write down a few to several to a bunch of quotes that I like and that I can see a pretty clear path toward using … somewhere in the piece,” says Irion. “I look at those quotes, and as I’m doing that, the architecture of the story begins to take shape in my mind, and I begin to see where I want to use certain sources. There’s probably going to be one or two sources who appear throughout the piece and several subsidiary sources who might just pop in once or twice. It will identify for me which are the most impactful, trenchant quotes from those sources, and those will actually be the starting point of my narrative. … Once I’ve got those down, something interesting happens. … If you’re writing a 3,000-word piece, pick the best quotes from those sources and type them in … you realize that you have 300 to 400 words already there … you already have a starting point.”

Personally, once I’m pretty deep into the construction of a feature article and a deadline is rapidly approaching, I find that writing out of context is much easier than immediately finding a place for any new addition. In the final hours of the writing process, I take time to plug these additions into place.

On a final note, when crafting a feature, I’m careful to keep all of my writing. It may feel gratifying to delete large portions of text that you no longer feel are necessary, but avoid such temptation! Nothing is more frustrating than later needing something that’s already been deleted. Instead of deleting this text, relegate it to a separate document, a boneyard of sorts, for your future reference.