No article, whether it be news, feature, or opinion, can consist only of facts. If an article were all facts, it would be boring and would hardly entertain your audience—you don’t want the reader to be more interested in reading the periodic table than she is in reading your work. All articles incorporate some narrative or storytelling elements. In fact, it’s often easy to attain narrative from the simplest primary sources; for generations, journalists have evoked narrative from documents as mundane as police reports.

Consider the following description of narrative taken from an article titled “Skip the Salad, Pass the Meat” by Robert L. Bryant Jr. and published in the Columbia Journalism Review: “Narrative, in this sense, is the red meat of journalism, the sinew of facts interlocked, the relentless march of cause and effect, of progression from A to B to C, of how things happen.”

In an e-mail interview, Roy Peter Clark, senior scholar at the Poynter Institute, explained to me how he sees narrative in broad terms. “For me,” writes Clark, “the key distinction is between reports and story. The purpose of reports is to transfer information. But the purpose of stories is to transfer experience. A narrative—with its scenes and dialogue—transports the reader to another time and place. It doesn’t just point you there; it puts you there.”

All articles have some elements of storytelling or narrative. Even news articles that are generated by newspapers and wire services, like the Associated Press (AP), have narrative elements. For example, the AP will construct fifteen to twenty optional ledes per week for big and breaking news stories. These types of ledes were once only intended for “P.M.” (after-work) readers but are now typical of stories disseminated at any time. Such narrative ledes are more engaging, provide context, and make for an easier point of entry. Because the reader is likely familiar with the headline because it has been broadcast via radio, Internet, or cable news, using narrative, perspective, and imagery may provide a novel way to attract the reader.

Consider the following two ledes the AP constructed in the wake of Terri Schiavo’s death. Terri Schiavo was a woman in a persistent vegetative state that lasted fifteen years. After a long court battle between her husband and parents, her feeding tube was removed in 2005.

Here’s the “traditional” or newsy lede that the AP would typically run:

With her husband and parents feuding to the bitter end and beyond, Terri Schiavo died Thursday, thirteen days after her feeding tube was removed in a wrenching right-to-die dispute that engulfed the courts, Capitol Hill, and the White House and divided the country.

Here’s the more narrative “alternative” lede:

She died cradled by her husband, a beloved stuffed tabby under her arm, a bouquet of lilies and roses at her bedside after her brother was expelled from her room. In death, as in life, no peace surrounded Terri Schiavo.

Especially with newspapers, the use of narrative elements is becoming increasingly popular in both news and feature articles. Consider the following observation made in an article titled “I’ll Be Brief” written by Carl Sessions Stepp in the American Journalism Review:

Readership worries definitely are helping drive the trend toward daily storytelling. Research by Northwestern University’s closely watched Readership Institute has found “strong evidence that an increase in the amount of feature-style stories has wide-ranging benefits.” A more narrative approach to both news and features, the institute said, can raise reader interest, especially among women, in topics from politics to sports to science. “Newspapers that run more feature-style stories are seen as more honest, fun, neighborly, intelligent, ‘in the know’ and more in touch with the values of readers,” it said.

Some may think there’s little room for narrative in newspaper pieces, which are short and tightly budgeted. This argument, however, is unfounded. Jack Hart, a long-time editor at The Oregonian and a Pulitzer Prize winner, teaches writers that shorter narratives, while working within a shorter time span and using fewer characters and scenes, must be just as dramatic as longer pieces. Furthermore, Hart argues that three well-constructed details are all that is needed to establish a scene for the readers.

It takes a lifetime to figure out how to incorporate narrative elements into article writing. A good place to start learning more about narrative is by reading the work of creative or literary nonfiction writers. I highly suggest picking up a copy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and reading through a few issues of Harper’s or The New Yorker.

Personally, my understanding of narrative has been heavily influenced by Roy Peter Clark. Many of the teachings presented here are inspired by his book Writing Tools. I highly recommend reading this book and internalizing its accessible content.

Characters are central to any narrative, and characters need to be developed.

When developing characters for your story, here are some details to consider:

Keep in mind that when developing a character, it’s always best to show rather than tell; in other words, use details rather than adjectives to flesh out your characters.

In an article from Details titled “The Overheated, Oversexed Cult of Bikram Choudhury,” writer Clancy Martin does an excellent job of developing Bikram Choudhury’s character. Choudhury is the über-rich, prurient, flamboyant, and excessive founder of Bikram Yoga, a type of yoga that involves extreme heat.

Choudhury has other quirks too. He says he eats a single meal a day (chicken or beef, no fruit or vegetables), drinks only water and Coke, and needs only two hours of sleep a night. Then there are the stories about him having sex with his students. When I ask him about this, he doesn’t deny it—he claims they blackmail him: “Only when they give me no choice! If they say to me, ‘Boss, you must fuck me or I will kill myself,’ then I do it! Think if I don’t! The karma!”

This story did such a good job of exposing Choudhury that it haunted him two years after it was written. In 2013, Choudhury was accused of sexual harassment by a female student.

Although narrative existed long before cinematography, it’s sometimes helpful to make references to camera work when discussing narrative.

Setting up a scene or setting is important. Just as a filmmaker uses a variety of shots, from close up to long, in order to capture a scene, a writer can use descriptive language to do the same. Whether you want to examine blood spatter at the crime scene more closely or pan out and describe the verdant and peaceful neighborhood in which the violent crime took place is your decision and can make for good narrative.

When setting up a scene, keep in mind that you want to do your best to help your readers visualize what you’re talking about. Consider your five senses: sight, smell, touch, sound, and taste. Notice important details that may otherwise have been overlooked. If you’re on-site and thus immersed in a scene, take a mental (and digital) snapshot of your surroundings. Consider the time and place. Is it so hot that you want to take your sweatshirt off, or is it so cold that you want to huddle underneath a dozen comforters? Think about the scene you want to write for several hours or even several days.

Consider this lede from an article titled “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?” which was published in The Atlantic:

Yvette Vickers, a former Playboy playmate and B-movie star, best known for her role in Attack of the 50 Foot Woman, would have been 83 last August, but nobody knows exactly how old she was when she died. According to the Los Angeles coroner’s report, she lay dead for the better part of a year before a neighbor and fellow actress, a woman named Susan Savage, noticed cobwebs and yellowing letters in her mailbox, reached through a broken window to unlock the door, and pushed her way through the piles of junk mail and mounds of clothing …

This lede does a great job of setting up a gruesome and depressing scene—a mummified body in an unkempt apartment. Notice how the author provides descriptions that are like close ups (“cobwebs … in the mailbox”) and descriptions that consider the entire setting (“piles of junk mail and mounds of clothing”). Anybody reading this lede can imagine how sad it must be: a one-time starlet left dead for months in a filthy apartment.

When doing research for a story, it’s important that you’re proactive and seek out details that will engage the reader. As Margaret Guroff, features editor at AARP The Magazine advises, “When you’re describing anything, you want to have details to pick from so that what you choose is something that moves the story.”

When setting up a scene, you may also want to consider the “reality effect.” This term was coined by Roland Barthes in the 1960s and refers to a description that alone is meaningless, but taken in context of the entire piece it provides a sense of reality. For example, describing an overturned Tiffany lamp at a crime scene may mean little by itself but provides a “real-world” sensibility for an article. Keep in mind, however, that the “reality effect” should be used sparingly. As with all other aspects of article writing, words are precious when constructing narrative.

In Writing to Deadline: The Journalist at Work, author Donald Murray suggests the journalist ask: “What surprised me when I was reporting the story?” He also recommends to “look for what isn’t there as much as what is, hear the unsaid as well as the said, imagine what might be.”

Surprise can come in the form of cliffhangers or plot twists and can be foreshadowed. The smart writer uses surprise to propel the reader toward the end. The tension of surprise can build like a rollercoaster inching its way up to an initial apex.

Surprise in storytelling is just as appealing as surprise in visual media. Think about all the television series that dangle the carrot of surprise in our faces. In the season six finale of the Showtime series Dexter, serial killer Dexter Morgan is caught with one of his victims by his sister, a lieutenant in the homicide division. At the season five midpoint of Breaking Bad, Walter White, the once-sedate chemistry teacher turned meth kingpin, is discovered by his brother-in-law, a DEA agent. And then there’s the megahit series Lost, which eventually tired its viewers with cliffhanger after cliffhanger.

In “The Case of the Vanishing Blonde,” published in Vanity Fair, author Mark Bowden uses surprise to explain how a young Ukrainian woman was taken from her hotel room and raped. In this real-life story, private detective Ken Brennan agonizes over how it happened.

Unless this crime had been pulled off by a team of magicians, the victim had to have come down in the elevator to the lobby and left through the front door. The answer was not obvious, but it had to be somewhere in the video record …

Through some astute detective work—and after several paragraphs of text—Brennan finally figures out how the perpetrator, a large man with glasses, committed the crime. He smuggled the woman out of the hotel in a suitcase. Of note, the man’s involvement was foreshadowed earlier in the story.

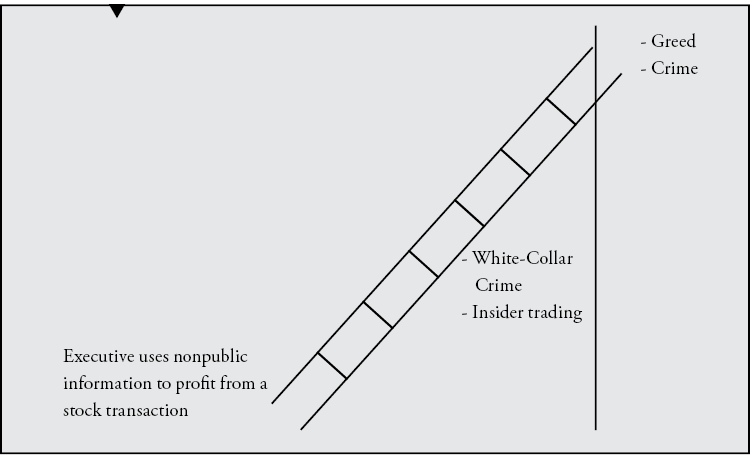

While infusing your story with narrative flair, think about the Ladder of Abstraction (popularized by S.I. Hayakawa in 1939). At the bottom of the ladder are concrete or specific images, and at the top of the ladder are general issues, topics, or sentiments that are universally appreciated. For example, if you gave your girlfriend or boyfriend roses for Valentine’s Day, you are dealing with both the bottom and top of the ladder: The roses are a concrete image that symbolizes the love and admiration that you feel for your lover.

In the Nimruz province of Afghanistan, which borders both Iran and Pakistan, there’s little water. Some of the water the residents of this province receive comes from Iran through the Lashkari Canal. In a New York Times Magazine article, Luke Mogelson uses the Ladder of Abstraction to compare the perceived width of the pipe providing water with Afghani sentiment for Iranians. The width of the pipe is a concrete image at the bottom of the ladder, and Afghani sentiment for Iranians is at the top of the ladder.

“I found,” writes Mogelson, “that you could gauge people’s general attitude toward Iran by how big they said the pipe was: An especially embittered official would swear its diameter measured no more than a couple of inches, whereas a frequenter of Iranian medical facilities, say, might call it a four-inch pipe.”

We find another example of the Ladder of Abstraction in a New York Times article titled “True Blue Stands Out in an Earthy Crowd” by Natalie Angier. According to the article, scientists have taken a greater interest in complexities of the color blue and its appearances in the natural world. In the piece, the author writes about blue at the lowest rung of the Ladder of Abstraction—specific animals and fruits that, in some way or another, exhibit the color blue. She then moves up the Ladder of Abstraction to discuss how blue is associated with creativity, calmness, depression, and so forth.

Just as a ladder is most stable at the bottom, where it rests on the ground, and the top, where it abuts a wall, the Ladder of Abstraction is best understood at either the bottom or top. The middle of the ladder—which is neither fully specific nor fully abstract—can get quite confusing. A good writer will mind this middle part and work especially hard to explain it. For a writer with the ability and patience, the payoff for covering the middle of the ladder can be great. For example, New York Times writer David Kocieniewski won a Pulitzer Prize in 2012 for his series of articles “that penetrated a legal thicket to explain how the nation’s wealthiest citizens and corporations often exploited loopholes and avoided taxes.”

Much of what we write about is at the middle of the Ladder of Abstraction: business, science, art, politics, sports, and so forth. When you write, it’s helpful to keep the Ladder of Abstraction in mind. More specifically, learn when to provide examples and explain things in a greater context. Also, make sure to transition into examples and general thinking. Don’t be too abrupt with your writing.

The juxtaposition or contrast of two seemingly disparate objects or ideas can make for great copy. It tickles the reader’s fancy and makes your narrative shine.

Most people would think that suicide bombers in Afghanistan and elsewhere would care little about their own safety, but as Mogelson points out, these people are often cowardly when fired on—a strange juxtaposition.

… these men, who are planning to blow themselves up, always become frightened when you open fire on them. As soon as the shooting starts, the suicider runs and hides. He doesn’t want to be shot. He is here to die, but he is scared of bullets. It’s strange.

Sometimes the best way to explain one of the key characters in your story is to provide a backstory or short description of the character’s past. Backstory is similar to a profile but focuses only on the aspects of a character that are important to the story. A few lines of backstory can help readers understand the person who they’re reading about and her intentions and capabilities.

In a story titled “What Happens in Brooklyn Moves to Vegas,” we meet Tony Hsieh, an entrepreneur who founded the online shoe company Zappos.com. Hsieh now wants to relocate all 1,200 employees of his company to downtown Las Vegas and attract other businesses to the area—a sort of gentrification project. He wants to build a new city that’s community focused, replete with random and “serendipitous” interactions among its citizens. It’s a novel idea, but will it work? The article’s author, Jon Kelly, uses Hsieh’s backstory to help the reader understand that if anybody can successfully complete this lofty project, it’s Hsieh.

Though Amazon bought Zappos in 2009 for $1.2 billion, Hsieh still runs the company, and he has endeavored to keep alive its zany corporate culture. This includes a workplace where everyone sits in the same open space and employees switch desks every few months in order to get to know one another better.

From this backstory, we understand that because Hsieh has already built a billion-dollar company based on a corporate culture that he hopes to mirror in his new city, he has a good chance at succeeding.

Well-chosen analogies, metaphors, and similes can strengthen arguments and add narrative flair. Consider the following simile. (A simile uses like or as to compare two things.) It concerns the color blue and is taken from The New York Times article “True Blue Stands Out in an Earthy Crowd.”

Another group working in the central Congo basin announced the discovery of a new species of monkey, a rare event in mammalogy. Rarer still is the noteworthiest trait of the monkey, called the lesula: a patch of brilliant blue skin on the male’s buttocks and scrotal area that stands out from the surrounding fur like neon underpants.

A reader who isn’t a biologist may have trouble conceptualizing a blue lesula, but thanks to this wonderful simile written by author Natalie Angier, we can imagine that the blue lesula looks like a pair of neon blue underpants. (Personally, I imagine a thong reminiscent of something Sacha Baron Cohen’s character Borat may wear.)

Later on, we learn that blue in nature exists in two forms: pigment and figment. Pigment is chemical color, and figment is structural color. Obviously, this concept is difficult to appreciate without further explanation, so Angier uses a metaphor that takes the form of an analogy to explain what figment or structural color is.

Structural blues are essentially built of soap membranes trapped at just the right orientation and thickness to forever glint blue.

An astute reader may question the difference between a metaphor and an analogy. A metaphor uses a conjugation of the verb to be in order to compare two things. For example, “the moon is a giant white saucer” is a metaphor. Metaphors are often used by poets and aren’t necessarily bound by logic. Analogies, though, are bound by logic and express relationships.

Metaphors and similes can both be analogies—in fact the best ones often are. Consider the following simile and analogy, which explains why looking at objects in the night sky is difficult. It’s taken from Robert Irion’s article “Homing In On Black Holes” from the Smithsonian. For ease of understanding, I display the simile in context.

The blur of Earth’s atmosphere has plagued telescope users since Galileo’s first studies of Jupiter and Saturn four hundred years ago. Looking at a star through air is like looking at a penny on the bottom of a swimming pool. Air currents make the starlight jitter back and forth.

If you want to use an analogy to explain a concept in your piece but are unsure of the proper one to choose, consider asking a source for an apt analogy. Scientists and other professionals are often asked to explain their work in terms that the general public can understand; thus they’ve often managed to test the effectiveness of several analogies and have found the best ones.

Irion has some useful advice on metaphors and figurative elements: “A metaphor for a general audience only works if you can come up with something that can be easily visualized or that they can relate to something from their everyday experience. Places in stories where I try to look for tangible and effective metaphors are in explanatory sections when I’m trying to explain how something works, how some scientific process unfolds … or something that’s remote from our everyday experience. …

“Always ask the person who you’re interviewing if they have ever come up with useful comparisons when they speak with a public audience or friends and colleagues because often the researchers—especially if they have some experience with giving interviews with reporters—will have a way of putting things that can be very useful to helping you develop your own appropriate metaphor. What that kind of question does is help activate a different part of the scientific brain, and [the interviewee will] begin to talk about things more accessibly, even if they don’t come up with that useful comparison that you can adapt. Maybe they will help you get started in the right direction with some comparison, and then you, as the journalist, can refine the metaphor and make it appropriate or more technically accurate.

“Coming up with metaphors is a challenge; you have to think about it, and you have to ask for help. Sometimes [you can talk] about the story with your peers and try to get some suggestions for a fresh metaphor that will bring that section of your story alive for readers. It’s hard and it’s something that you have to play around with, and this is where your editor can be your best ally. You try a metaphor—even if it’s a little strained initially—and then your editor can say, ‘You’re going in the right direction, but let’s see if we can make this a little more accessible or a more common experience.’ You work together to find something that works.”

An effective but subtle example of metaphor use involves the trope. A trope uses a single verb in a figurative or metaphorical sense. Often this verb choice gets to the meaning of the sentence in a circuitous or roundabout way. For example, when people “harvest” financial benefit, the verb harvest evokes images of farmers harvesting their crops.

Using specific names of people, animals, objects, and so forth in your article can provide for excellent narrative. A name can be distinct, symbolic, and telling. In some cases, once you hear a name, you can ascertain what that name signifies. For example, the Terminator, famously played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, probably doesn’t go around picking daisies, and if he does, he surely doesn’t do so onscreen.

Imagine you just went to a New Year’s party that was played by all your favorite hip-hop and rap artists. Simply telling your friend, “A bunch of great musicians rocked the house!” means little. But telling your friend that “Busta Rhymes, Kid Cudi, Mos Def, Lupe Fiasco, Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg (Snoop Lion?), Jay-Z, Ghostface Killah, and the rest of the Wu-Tang Clan rocked the house!” means more. (I realize that getting all of these guys in one place is nearly impossible. Their styles differ, the cost would be outrageous, and there may be residual hard feelings from some East Coast-West Coast beef.)

Roy Peter Clark is a master at capitalizing on the value of names. When Joe Paterno was involved in the sex-abuse scandal at Penn State, the news deeply affected football fans everywhere, including Clark. In an opinion article titled “Joe Paterno and the stained soul of Penn State,” Clark elegizes the once great Paterno, who had fallen from grace.

An author could not invent a better name: Joe Paterno. St. Joe, father of a holy family of student athletes. JoePa. Papa Joe. Pater, as in Latin for father. Eternal paternal Paterno.

Our father, who art in trouble, hollow be thy name.

In a more humorous take on the value of names (and name-calling), consider this example of video-game developer Jonathan Blow laying into the social network game FarmVille. It’s taken from an Atlantic article titled “The Most Dangerous Gamer.”

In one talk, Blow managed to compare FarmVille’s developers to muggers, alcoholic-enablers, Bernie Madoff, and brain-colonizing ant parasites.

In addition to demonstrating Blow’s sentiments with choice names, the author of the piece also used alliteration—repetition of bs and ls—to add more narrative zing.

Smart writers can further bolster the storytelling appeal of their work by playing with the words they choose. There’s a mechanical quality to words that can be leveraged when writing. Examples of wordplay include alliteration, assonance, and repetition.

Alliteration is the repetition of certain syllables such as s, t, l, b, and so forth. Consider the following example of alliteration used to describe video-game developer Jonathan Blow. In this example, the letter s is alliterated.

Blow’s rigorous personal codes reached their peak severity when he was a child. Authentic spiritual self-reliance became his fixation, escapism and superstition his greatest enemies.

Another example of wordplay is repetition. The mere repetition of key words can engage the reader, evoke emotion, and spark the imagination. Great orators such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King Jr. used repetition for effect. For example, consider a quotation of King’s that plays on the word “drum major.” As pointed out by Roy Peter Clark in a CNN Opinion piece, drum majors hold a special station in African American culture. (To learn more, watch Drumline starring Nick Cannon.)

Yes, if you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all the other shallow things will not matter.

An inaccurate and contentious paraphrase of the quotation was inscribed on King’s memorial in Washington, DC: “I was a drum major for justice, peace and righteousness.” The paraphrased quotation gave the very false impression that King was claiming to be a drum major and, as pointed out by famed poet Maya Angelou, unjustly made King sound like “an arrogant twit.” Angelou told The Washington Post, “He had no arrogance at all. He had a humility that comes from deep inside. The ‘if’ clause that is left out is salient. Leaving it out changes the meaning completely.” Subsequently, plans were made to remove the inscription.

In an opinion article titled “A neighborly gesture is a reminder of the kindness hiding inside of us,” Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and commentator Connie Schultz uses repetition of the word “tomorrow” to reinforce mutual acts of kindness that she shares with her next-door neighbors.

Tomorrow, I vowed as I stepped out the front door to retrieve our newspapers.

Tomorrow I will be the one who races to the end of the driveway to pick up the papers.

Tomorrow I will deliver our neighbors’ newspapers next to their garage door, right where they like them.

Much like an eighteen-foot king cobra, a long sentence is difficult to control. But a short sentence, a garter snake of a sentence, can pack a venomous punch. Similarly, short paragraphs can be used for effect—as is the case with paragraphs found in news pieces that adhere to the inverted-pyramid structure.

A good example of the power of short sentences embedded in short paragraphs is aptly demonstrated in a piece by ABC news writer Jonathan Karl. In his article titled “A Romney-Biden Administration? It Could Happen,” Karl explains how a seemingly impossible occurrence, a split executive office, could transpire should there be an even split in electoral votes during the 2012 presidential campaign.

It sounds crazy. It would be crazy. But it is possible that this election could result in a President Romney and a Vice President Biden.

Let me explain.

If there is a tie in the electoral college (and, as I explain below, there could be), it will be up to the newly elected House of Representatives to elect a President and the newly elected Senate to elect the Vice President.

In another opinion piece for CNN News titled “Stephen Colbert’s Got Sway,” Roy Peter Clark reflects on the satire of faux-conservative political personality Stephen Colbert. He closes this opinion piece with the following.

When I was the age of Colbert’s legion of fans, I turned to the novels of Orwell, Huxley, and Burgess to sharpen my skepticism toward the language of those in power. Such fiction is likely to wane in influence in an era when so many read less and care less.

In its place is something quite different but, in its own way, quite good: comedy and satire shining a disinfecting light on the language of scoundrels. Turn on the telly. Pass the popcorn.

You’ll notice that the last two sentences are short in order to convey a simple message: Let’s not lament the inevitable outmoding of yesterday’s great cynics, satirists, and skeptics; instead, sit back and enjoy The Colbert Report.

An experienced writer can also use sentence fragments in lieu of short sentences, which have a subject and verb. Such fragments are used for emphasis, inventory, shock, intensity, and informality.

Consider the following:

I just heard that Jonathan fell down several flights of stairs and sustained great injury. Can you imagine? Both arms, his pelvis, his right leg, and his coccyx. Poor kid!

Finally, some writers like to punctuate a series of long sentences with a short sentence, thus providing some relief for the reader—kind of like an oscillating fan blasting the reader with a current of cool air.

I debated whether to advise the reader on the use of longer sentences: I mulled it over for days, weighed the pros and cons, and e-mailed Roy Peter Clark for advice on the matter. (You’ll notice that this sentence is long and reflects this agonizing decision.) Roy Peter Clark advised me to instruct the reader on the use of short, medium, and long sentences.

When using longer sentences as narrative fodder to convey emotions such as monotony, longing, pain, frustration, confusion, angst, and so forth, make sure you avoid run-ons. Even with longer sentences, however complex, one interrelated idea must be conveyed. Be sure to place the principal subject and verb close to each other (thus forming a right-branching sentence).

In the following example, the subject my son is separated from the verb misbehaves by a long nonrestrictive clause. Consequently, the meaning is muddled.

My son—who takes the car keys without permission, stays up all night partying, steals money from my wallet, vandalizes street signs, and skips school regularly—misbehaves.

The sentence would read better with the subject and verb in closer proximity.

My son misbehaves; he takes the car keys without permission, stays up all night partying, steals money from my wallet, vandalizes street signs, and skips school regularly.

When writing narrative, many writers prefer to write in the historical past and occasionally shift to the historical present tense for effect. Consider the following.

I had the perfect Sunday morning. My kids brought me breakfast in bed: freshly squeezed juice, crunchy turkey bacon, and fluffy blueberry pancakes. After breakfast, I took the dog for an invigorating walk through the neighborhood. After the walk, I took a long, hot shower. I couldn’t help but marvel that life is good.

This bit of narrative recounts an enjoyable experience and is written in the historical past. The only time I shift to the present is when I declare that “life is good.” This shift to the present tense emphatically underscores an enduring sentiment.

Sometimes relying on the historical present works, too. The historical present uses the present tense to describe past events and can energize and invigorate a story. Consider the following.

Sunday morning is perfect. My kids bring me breakfast in bed: freshly squeezed juice, crunchy turkey bacon, and fluffy blueberry pancakes. After breakfast, I take the dog for an invigorating walk through the neighborhood. After the walk, I take a long hot shower. I can’t help but marvel that life is good.

Note that, for effect, headlines are often written in historical present: “President Obama goes to Asia.”

When I was in my late twenties, I lived in an apartment next door to a fifty-something-year-old gentleman who loved music. But he didn’t love only the music from his youth (early 1960s?); he loved music from every generation. I’d be just as likely to hear Frank Sinatra or Miles Davis blaring from his stereo speakers as I would Biggie Smalls or Mike Jones.

My brother, who lived in the apartment directly above me, seemed fixated on the idea that this older guy could enjoy modern hip-hop and rap. Several years later, as a professional writer, I came to admire this guy for being able to keep abreast of emerging artists and still appreciate greats from musical generations past. The ability to stay current with respect to popular culture is integral for a journalist or writer. Allusions to popular culture can help you connect with your readers.

Unfortunately, some people consider allusions to popular culture and new media lowbrow. This mischaracterization of popular media as less weighty than traditional media is likely a result of bias. According to media theorist Marshall McLuhan, “The student of media soon comes to expect the new media of any period … to be classed as ‘pseudo’ by those who acquired the patterns of earlier media, whatever they may happen to be.”

For those who question the value of popular media, it should be pointed out that, as argued by author Steven Johnson, popular media is both engaging and complex. In his book Everything Bad Is Good for You, Johnson writes the following.

For decades, we’ve worked under the assumption that mass culture follows a steadily declining path towards lowest-common-denominator standards, presumably because the “masses” want dumb, simple pleasures and big media companies want to give what they want. But in fact, the culture is getting more intellectually demanding, not less.”

Johnson argues that popular media such as television and video games is actually making people smarter. (Johnson’s argument lacks solid scientific proof, but his hypothesis is interesting.) Furthermore, television narratives are becoming complex and entertaining enough to rival any book. Many smart people spend their time not only reading books but also watching television shows such as Breaking Bad and playing video games such as World of Warcraft. In fact, Dr. Robert J. Thompson, the founding director of the Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture at Syracuse University, claims that we are in the midst of the Second Golden Age of Television. Today, television shows are more cerebral, cinematic, and literary than ever before.

Granted, some allusions are tired, and a writer should resist such low-hanging fruit. It’s passé to refer to Arnold Schwarzenegger as the “Governator” or to “super-size” anything—most of all your waistline. And at this point, it’s probably safe to say that most people revile anything having to do with “Gangnam Style.” But some allusions are fresh and entertaining.

A source tipped me off to the following headline on news and gossip website Gawker. It does a cute job of emulating a current popular-culture phenomenon: the text message.

OMG Did Taylor Swift Cheat on Conor Kennedy with His Cousin? Text Me Back When U Get This

For anybody who may have missed it (and for anybody who cares), in the summer of 2012, Conor Kennedy, a high school student and Robert F. Kennedy’s grandson (John F. Kennedy’s grand-nephew), was dating music star Taylor Swift. Taylor Swift was also linked to Patrick Schwarzenegger, Conor’s cousin—hence the headline.

In a short article from The New York Times Magazine titled “Is There Mood Lighting, Too?” writer Hope Reeves notes that some cow farmers are building dual-chamber waterbeds for their cows to sleep on. Aside from being more comfortable, the waterbeds are cheaper than replenishing a supply of sawdust and help the cows produce higher-quality milk. The author jokes about how “romantic” it is for two cows to sleep on a waterbed and makes a cultural allusion to the classic-rock band the Eagles.

They are charging more for their higher-quality milk and saving about $6,000 a year in sawdust piles—the cow’s previous sleeping platform. Imagine what might happen if all-night Eagles songs were added to the mix.

Sometimes the astute writer will simply realize when the subject of their article is making a popular-culture reference, as is this case with an Associated Press news piece titled “Obama accuses Romney of suffering from ‘Romnesia.’”

Obama, a broad grin on his face, borrowed heavily from the style of comedian Jeff Foxworthy, known for his “you might be a redneck” standup routines. The comedy offered the president a warm-up of sorts before Monday’s final presidential debate in Boca Raton, Fla.

“If you say you’ll protect a woman’s right to choose, but you stand up at a primary debate and said that you’d be ‘delighted’ to sign a law outlawing that right to choose in all cases, man, you’ve definitely got Romnesia,” he said.

Allusions can be made to either traditional media—most commonly, Greek mythology, Shakespeare, or the Bible—or to popular media. A good writer will have a broad enough knowledge of traditional media and popular media and be able to make allusions to both.

States Robert J. Thompson, “If you have a writer who is writing with a broad knowledge of American culture and a broad knowledge of world literature and a broad knowledge of the big three—the Bible, Greek mythology, and Shakespeare—you can work in that stuff in a way that makes sense. If you’re simply trying to do it to sound smart, it nearly always falls on its face.

“You can sprinkle an article with high-brow references, and if you write them well, they don’t have to be lost on people who aren’t well read on those kinds of things, and the same is true of popular references as well. You don’t have to actually know this stuff to understand a reference in an article. … It all boils down to whether it is written well. Readers don’t have to have seen a single episode of Here Comes Honey Boo Boo to understand a reference to Honey Boo Boo because they’ve heard about it. They don’t have to have seen a production of Hamlet to understand ‘good night, sweet prince’ or ‘to be or not to be.’

“In many cases, references to high culture tend to flatter an audience because they think they’ve gotten it even if they don’t know intimately at all what its context was. We see people slinging around classic canonized literary stuff all the time, and the reference is understood even though the person may never have read the novel or seen the play.”

Roy Peter Clark writes, “I like writers who have both Old School and New School sensibilities. Who can refer to Lady Gaga and Thomas Aquinas in the same paragraph. It does not concern me if my readers do not recognize a particular allusion. I will explain it to them or make it clear from context.”

Many writers who create work for the public do their best to follow the popular media. For many—including me—it provides the perfect justification for spending four hours a day watching television and movies. “It’s part of the business,” says veteran journalist Holly G. Miller. “You have to know what’s going on; you have to know what people care about; you have to see what movies people are going to.”

A writer, however, should keep in mind that beginning with the advent of cable television, popular culture has become increasingly fragmented.

“If you make a reference to a really good quote in Breaking Bad or Mad Men,” says Thompson, “you’re going to get a few people from the two million people who watch those shows who are going to get that reference in great depth and with great energy. But you are going to get a lot of people who aren’t going to catch it because—as good as those shows are and as much as they’ve been rewarded—a lot of popular culture is relatively fragmented. We are not in the era of I Love Lucy and The Ed Sullivan Show where everybody was watching the same thing at the same time. Our best popular culture is watched by 1 percent of the population … we have 300 million plus people in the country, and three million is a pretty big hit on a cable show.”

Besides watching television shows such as The Simpsons or Family Guy, a writer can gather information about the current state of popular culture by following several social media and online resources, including those at the Pew Research Center’s website www.journalism.org. On this site, you will find indices tracking new media, talk shows, and campaign and news coverage. Additionally, websites such as Reddit and YouTube generate lists of news and video that reflect the current cultural zeitgeist.

Many good writers choose to spice up their prose with colloquialisms often derived from music, television, Internet slang, viral memes, and so forth. When used in moderation, words such as swag, bling, playa, baller, blowin’ up, tebowing, and so forth can be refreshing to the reader.

Margaret Guroff, features editor at AARP The Magazine, invites writers to use new words in their stories. “English is a living language. It’s always changing. The question is whether it’s the right word.”

Interestingly, and probably much to the chagrin of conservative grammarians, many examples of today’s slang are nouns that are used as verbs. For example, you can google the price of a television and then text the price to a friend.

The number of elements you cite can have a dramatic effect on your narrative.

Consider the following.

I am happy.

Okay, so I’m happy. The statement is absolute and probably explains all that anybody needs to know about me right now. Maybe I just finished eating Thanksgiving dinner with my family, and we just plopped ourselves in front of the boob tube to watch the Detroit Lions play the Chicago Bears.

I am happy and excited.

So I’m not only happy, but I’m also excited. My happiness has crossed over from mere contentment to something more—something that complements my happiness. Maybe I’m both happy and excited because my favorite football team, the Detroit Lions, scored a touchdown during the Thanksgiving Classic.

I am happy, excited, and optimistic.

This sentence has an inclusive quality to it—as if these three adjectives comprise my current state. It’s like a closed set in mathematics; it has boundaries. This list of elements completely explains a situation. Taken together, these elements can imply hope. For example, maybe in the final seconds of the game, the Lions scored a touchdown and nailed the field goal, putting them seven points in front of the evil Bears; in other words, it looks like the Lions will win.

I am happy, excited, elated, optimistic, contented, cheerful, overjoyed …

This sentence is similar to an open set in mathematics with no boundaries to the number of elements that can be tacked on. You can string more adjectives similar to the word happy onto this sentence, and they probably describe my emotional state. Maybe the Lions won, and after the game was done, I checked my Mega Millions ticket and found I had just won $135 million.

A lot of Internet writing is short and to the point. Paying attention to the number of elements you include in a story can make your Internet writing more concise. Many professional writers realize this fact and carefully choose the number of elements they use when writing articles or blog postings.

In 2012, Yoselyn Ortega, a nanny in New York City, fatally stabbed two young children under her care and then injured herself. It was a terrible and unexpected tragedy. Shortly after the stabbing, in a blog posting titled “The Kids Aren’t Safe With Me,” Lori Leibovich, a lifestyle editor with The Huffington Post, wrote about her own close call with a nanny who had a “psychotic break.”

The lede starts with one simple concept (and the gist of the entire piece): By the nanny’s own admission, the kids weren’t safe with her.

“The kids aren’t safe with me.”

The voice on the other end of the phone was strangely calm and matter-of-fact. It was my nanny (whom I’ll call Liane), and she was home with my two young children.

Later, Leibovich offers a bit of backstory to express how great she thought the nanny was when she hired her. In one sentence she includes two elements to explain how the nanny instantly appealed to her young son. During their first encounter, the nanny not only played Legos with the boy but also explained mythology. These two elements complement each other; the nanny would engage the boy in two ways, with physical toys and fantastic ideas.

She got on the floor with my son and helped him construct Lego castles and introduced him to mythology.

In another explanation of the nanny’s backstory, Leibovich uses three elements to expound on just how great she and her husband thought this nanny was before they hired her.

Once we met Liane, we knew we’d hire her. Her references confirmed what we thought: Liane was loving and smart and fun.

This statement includes three elements that reinforce our understanding that on the surface the nanny is everything a potential employer would desire: She’s loving, smart, and fun. What else could anyone want from a nanny? Apparently, she’s the total package.

As Roy Peter Clark explains in his book Writing Tools, including four or more elements in a sentence helps it break through “escape velocity.” It takes a sentence to excess and intentionally overloads your reader.

A while back, I was assigned an article that involved fruit diversity. After doing some research, I was amazed at how many varieties of fruit there actually are—even seemingly mundane fruits such as apples and oranges came in many varieties. I found that other journalists who write about fruit were equally intrigued by the variety and sometimes use lists that include several elements or examples to impress on readers just how many varieties of fruits there are.

In this travel feature from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel titled “Pick your own pumpkins, and apples, too,” writer Brian E. Clark impresses the reader with the vast number of apple varieties that grow on one single commercial orchard. The interesting names of the apples contribute more narrative flair.

Flannery said his orchard produces more than thirty varieties of apples, ranging from the old traditionals, including Macintosh, Cortland, Johnson, yellow and red delicious, as well as newer types such as Honeycrisp, Gala, Fuji, Snowsweet, and Cameo, which is Flannery’s favorite.

One final note about the use of elements—specifically as it relates to the use of two elements: As was the case with the examples above, two elements can complement each other or be compared with each other in terms of similarity. But two elements can also contrast each other.

Several years after the 9/11 tragedy, plans for a Muslim cultural center to be built near Ground Zero came to light. Several groups who felt that a mosque built near Ground Zero would be disrespectful seriously opposed this plan. In a CNN online opinion piece titled “Beware loaded language in Islamic center debate,” Roy Peter Clark cleverly used the controversy as an example to warn others of loaded language. In doing so, he contrasted two similar elements—Islamophobia and Islamofascism—to make a point. In other words, he uses “vs.” with irony.

And on the other, a new word has been coined to describe such expressions: “Islamophobia.” Meanwhile, the right focuses on the dangers posed by fanatics they call “Islamofascists.”

Islamophobia vs. Islamofascism. Not much wiggle room for moderate debate there.

One mistake that many writers make is trying to squeeze too many ideas into their stories. With the possible exception of resulting gastrointestinal distress, the practice is similar to overloading yourself at the $9.99 Chinese buffet—seven plates will make anybody sick! Normally, a good editor will realize that a writer has gone off track and rope him in with heavy editing.

Most good stories have one goal or purpose, and the angle of the story helps the writer achieve this goal. From the beginning, a writer transitions toward an ending that is always in sight. If a reader becomes lost and the promise of this ending is obfuscated, then the writer has failed.

“At its heart,” says Michael Howerton, managing editor at Contently and former editor at The Wall Street Journal, “every story is about one thing. Every story has one guiding principle … one idea behind it that is its engine. … When the story is about more than one thing, it becomes incoherent.”

I once wrote a thought feature about international medical graduates for an association magazine. International medical graduates are physicians who went to medical school in another country and come to the United States in order to do their residency training. The vast majority of these physicians end up practicing medicine in the United States and never return to their own countries. This phenomenon results in what experts have named “brain drain.” Brain drain refers to the unintended consequence of another country sending its physicians to the United States for training: a dearth of physicians in their own health-care system.

The training of international medical graduates is governed by an organization called the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates. In addition to evaluating and licensing these physicians, this commission also provides tools to help these physicians acculturate, including online tutorials and mentoring services. Even though the angle of my piece involved examining international medical graduates with an eye toward brain drain, while writing the story, I became infatuated with these acculturation services. I ended up trying to do too much with my article and unduly focused on issues that were outside the scope of my feature. After cutting hundreds of words out of my first drafts, my editor reminded me to stay on track and deal with brain drain, the issue at hand.

In order to keep a story on track, you may want to prioritize the story’s social network. In other words, the participants, witnesses, and experts should be pared down to the most relevant. You don’t want your work to read like Dream of the Red Chamber—a Chinese masterpiece that requires a genealogy in order to understand it. Keep in mind that when considering which characters to include in your work, you walk a fine line between truth and understanding. Strive to take the fewest literary privileges as possible with the intention of remaining as verifiable or factually accurate as possible.

As a somewhat cautionary tale, consider Ben Affleck’s movie Argo. Although an excellent movie, it downplayed Canadian involvement in the freeing of six American hostages in the wake of the 1979 Iran Hostage Crisis. Consequently, some have labeled the movie revisionist.

Another useful construct to consider when keeping a story on track is the complication-resolution model. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jon Franklin touts the complication-resolution model in his book Writing for Story. According to this model, every story has a complication, which can be a conflict or issue the story’s characters are dealing with. This complication causes tension as the characters in the story try to resolve it. Once the complication is solved or passes, there’s resolution.

Many—if not all—the stories that grip the world’s attention follow a pattern of complication, tension, and resolution. To illustrate, consider the story six-year-old Elián González, whose mother attempted to bring him by boat to the United States from Cuba in 1999. González’s mother drowned, but little Elián was rescued. He was entrusted to the care of relatives in Miami who wanted to keep him in the United States. Meanwhile, Elián’s father wanted the boy to return to Cuba. After a protracted legal battle, little Elián was returned to his father.

In Elián’s story, the complication was whether he would stay in the United States. The tension was all the legal wrangling that occurred and its accompanying overtones of the strained U.S.-Cuban relationship (a leitmotif that perched higher on the Ladder of Abstraction). This complication resulted in tension with characters on both sides of the issue that were fighting to keep Elián. The resolution was Elián’s eventual return to Cuba.

From a technical perspective, the proper use of transitions and topic sentences help the writer stay on track and keep the narrative flowing.

Transitions link sentences together. Here are some typical transitions used to link sentences together. These transitions are often found at the beginnings of sentences and are adverbs that end up modifying the sentences they precede.

In addition to using such specific words as transitions, the subject of a sentence may be repeated or implied in order to establish flow. Relevant quotations can also serve as transitions.

Finally, topic sentences introduce the information in a paragraph and help transition from one paragraph to another. A topic sentence is usually found at the beginning of each paragraph.

Imagine you’re living in Los Angeles and your friends invite you to come with them on a weekend trip to Las Vegas. You excitedly fill your backpack with the essentials and pile into the backseat of a car packed with your friends. You can’t wait to get to the Strip, chow down at the buffets, see a show, and maybe play the five-dollar blackjack tables.

Unless you get stuck in Friday traffic, the drive between LA and Vegas takes about four hours. But few people drive straight through to Vegas, especially on a road trip with buddies. You’ll likely make a pit stop to gas up, use the facilities, or grab a gyro at the Mad Greek in Baker, California. (Baker is home to the “World’s Largest Thermometer.”) These diversions are part of the fun.

An article is like a road trip to Vegas. It’s a journey that starts somewhere (Los Angeles) and ends somewhere (Las Vegas). Along the way, there are pit stops, such as restroom breaks and junk-food runs. In articles, these pit stops can take the form of anecdotes.

When written well, anecdotes allow the reader a vicarious, visceral, and emotional experience. Anecdotes are little stories with their own beginnings, middles and ends. For the most part, anecdotes are short, placed strategically, and reflect the theme, scope, and angle of the article.

While doing research, a smart writer will keep tabs on striking anecdotes. “While I’m researching a piece and I’m talking about it with my friends and family,” says Margaret Guroff, “I’ll make a note of which stories I’m telling them because these are the ones that stand out and these are the ones that are most reflective of what I want to tell the reader about the subject.”

Anecdotes may allow the writer to retreat from analyses and fact and encamp behind the fourth wall. In theater and film, the fourth wall is the imaginary wall that separates the play from the audience. Sometimes a character will break through this wall and address the audience directly. For example, in the 1970s television show Three’s Company, character actor Norman Fell, who played the landlord Mr. Roper, would sometimes turn to the camera and smile after he made fun of his wife. Fell’s brilliant facial expressions broke the fourth wall, and we, the audience, knew that he was sharing the joke with us. For a more recent example of a character breaking the fourth wall, check out Kevin Spacey’s performance in the political thriller House of Cards.

In addition to parodying and satirizing nearly every other imaginable literary device, from time to time, the characters on The Simpsons break the fourth wall and address the audience. Homer Simpson even broke through the fourth wall in The Simpsons Movie when he chastised the audience for being suckers and paying to see characters in a movie theater that they could have watched on television for free.

In a Best Life feature article titled “The New Age of Fatherhood,” author Jennifer Wolff Perrine skillfully uses anecdotes to illustrate the practice of wealthy single men paying huge sums of money for surrogate mothers to have their children. The anecdotes all involve highly successful professionals, including investors and financial advisors, who, for a variety of reasons, were single but still wanted a baby. These anecdotes are interspersed between the ethical, legal, and financial analysis of the issue. Incidentally, the piece also makes good use of the Ladder of Abstraction with specific anecdotes at the bottom of the ladder and the ethical, legal, and financial concerns higher up.

Well-chosen quotations can also contribute to the narrative of an article. Quotations make articles interesting and shouldn’t regurgitate facts, definitions, or statistics. Such information is better described in the author’s own words.

Many seasoned writers and reporters develop a feel for a useful quotation, especially when the quotation espouses the right sentiment. While interviewing or researching, they’ll stumble across something that’s best said by another person. Although there’s no foolproof method for coming up with great quotations, these useful guidelines should help you choose when a quotation should go into your article:

Keep in mind that choosing quotations to use in an article is a great responsibility that carries consequences. Holly G. Miller, an editor at The Saturday Evening Post and also a publications consultant, says, “As a writer, you have an incredible power to manipulate just by the quotes you pull out of an interview. … It’s a tightrope that you walk.”

Miller cautions against sticking too many quotations into your story. “You don’t want to be quoting a bunch of clones,” says Miller. “So if they all pretty much say the same thing, you need only one person to say it.”

Although it’s better to err on the side of too many interviews rather than too few, interviewing too many people poses its own risks. “When you talk to a lot of people,” says Miller, “the temptation is to make sure they are all included in the article. [Remember] that you’re not writing for the people who you’re interviewing; you’re writing for the reader. If somebody said stuff that really has no depth or didn’t add anything to the conversation, you have to leave them out.”

Although seldom used when writing articles, dialogue can be a useful tool. Dialogue is a discussion between two characters. Unlike quotations, which are heard and recorded, dialogue is usually overheard or meticulously reconstructed through interviews with both speakers and witness accounts. According to Roy Peter Clark, “While quotes provide information or explanation, dialogue thickens the plot. The quote may be heard, but dialogue is overheard. The writer who uses dialogue transports us to a place and time where we get to experience the events described in the story.”

In “The Case of the Vanishing Blonde,” Michael Lee Jones, a suspect in a rape case, is questioned by Detective Allen Foote. The dialogue between Foote and Jones does more to develop the narrative than any description in the author’s own words possibly could. It also hints at the detective’s anger and frustration over this unsolved case.

“Look, I’ve got a girl who was raped that week. Did you have anything to do with it?”

“No, of course not!” said Jones, appropriately shocked by the question. “No way.”

“You didn’t beat the shit out of this girl and leave her for dead in a field down there?”

“Oh, no. No.”

In conclusion, narrative is the lifeblood of any article; it’s what distinguishes a list of facts from an entertaining and engaging story. But just as with conventions of style, conventions of narrative take time to learn. No writer can craft a stylistically sound and narrative-rich story on the first go-around. Through the polishing and revision process, a piece can be imbued with narrative elements and the words can be changed into crisp, publishable, and alluring prose. Just as a painter layers watercolor, the writer layers effort and continues to tinker with a piece until it reads well. In part, this polishing process is what distinguishes journalism from science.

“Good narrative writing has a rhythm that unfolds, and the prose helps to shape the reader’s experience as they are sitting back and reading it,” says science writer Robert Irion. “The structure of paragraphs, the length of sentences, the emphasis within a sentence … all of this is important. It doesn’t necessarily happen on draft one. First drafts … are the most painful part of this whole process. Often what you’re doing initially is getting a bunch of stuff down so that you’re no longer staring at the blank screen.”

Ted Spiker, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Florida and former editor at Men’s Health, echoes this sentiment. “The thing I hate most about writing,” says Spiker, “is the first draft because I just hate getting it all down there. But when I feel like the draft is 80 percent there, that’s my favorite time. It’s like I have the foundation. Now it’s time for interior decorating … let’s dress this thing up. But it’s a fine line. … You want to be careful not to overdecorate because oftentimes tightening up and slimming down are the best parts of revision, but they are the places where you can muscle up your verbs, experiment with sentence structure, and turn a good story into a great one.”