The uninitiated may assume that reporting facts without the fluffy extras may be easy (and unromantic). But the truth is that writing news pieces can be a devilishly difficult skill to master. Beginning journalism students struggle with the inverted pyramid because, in addition to brevity, reporting in the inverted-pyramid structure requires analysis and evaluation—higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy (see Chapter 8). Consequently, it will probably come as no surprise that reporting news has been a breeding ground for many famous writers.

Years ago, most beginning journalists got their start reporting at the local newspaper. These journalists became experts at using the inverted pyramid and reporting news. Nowadays, with newspapers downsizing and media becoming increasingly fragmented, it’s feasible that many journalists never receive in-depth exposure to news reporting. Nevertheless, every journalist or writer of articles would benefit from understanding this discipline.

After communicating with many experts and doing much research, I’ve been able to conceptualize news articles as existing in several forms. The options I present are by no means inclusive.

The inverted pyramid is a funny structure. It’s a structure that many journalists spend a good part of their lives mastering and the rest of their lives questioning. No matter what its detractors claim, however, the inverted pyramid continues to have an enduring significance in the realms of news reporting and journalism in general.

“I think the inverted pyramid is an extremely useful device that serves a lot of stories well,” says Michael Howerton, a former editor at The Wall Street Journal. “There was a time when [journalists] thought that you had to move away from the pyramid because it’s such a limited version of storytelling and we have to be more magazine style, we have to be more feature style, we have to be more emotional with our writing. And I think that’s great, and I agree with all of those things. But the problem is that if you’re reading a newspaper and you have every story written in a magazine style, it’s too exhausting for the reader. Some stories are very well suited for the inverted pyramid. The inverted pyramid is great for writing strong, quick, and efficient prose.”

Although many people believe the inverted pyramid arose from necessity—early telegraph transmissions were costly and required prioritization of the news transmitted—more likely the inverted pyramid faded into existence at about the time of President Lincoln’s assassination. The inverted pyramid became more popular during the Progressive Era (1880 to 1910) and the rise of the Associated Press, which distributed fact-weighted news intended for all audiences. (As argued by author and thinker Steven Johnson, many of man’s greatest inventions and discoveries slowly materialize—few are, in fact, groundbreaking.) Furthermore, the development of the inverted pyramid and its summary news lede were likely moderated by the advance of science and higher education. Before the inverted pyramid became popular, news stories were often written in dandified prose that read more like fairy tales than modern news. The most important information was saved for last, and that was okay because it took several weeks for news to travel—nobody was in a rush for facts.

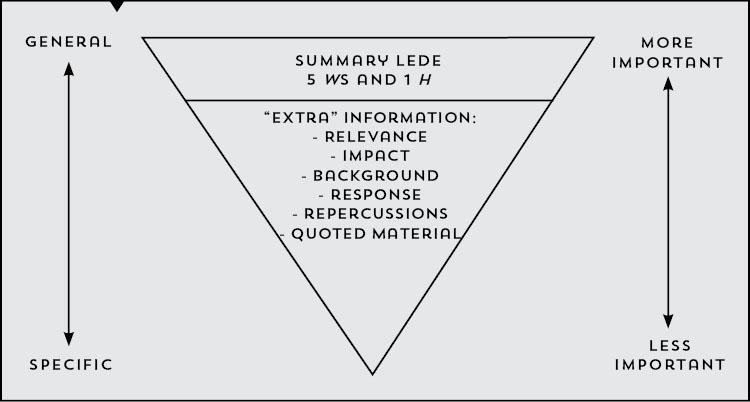

The inverted pyramid starts with a summary lede that addresses the five Ws and one H: who, what, where, when, why, and how. This information is normally introduced by an enticing detail or engaging sentence or two. The paragraphs following this lede paragraph present extra information in descending order of importance and from general to specific. Such “extra” information may describe relevance, impact, background, response, consequences, repercussions, and quoted material.

Even though stories written using the inverted pyramid are direct in their presentation of facts, they must still be relevant and engaging to the reader. Tom Linden says that the reader has “to know fairly quickly what [she is] going to get out of the story… the added value of the story.”

The sentences and paragraphs in a piece written in the inverted-pyramid style are typically concise. Sentences are often weighted at the end with nonessential elements preceding essential elements. Additionally, quotations are often broken into paragraphs. As with feature writing, grouping the quotations and input from experts is useful with a news piece written using the inverted pyramid.

On March 18, 2013, a story ran that exemplifies the chain of “breaking-news” reporting mediated by the inverted pyramid. At 5:43 A.M., the Chicago Tribune and the South Bend Tribune published a story titled “2 Killed, 3 Hurt When Small Jet Crashes into South Bend homes.” Here is the summary lede of the story, which, after a sentence of narrative, efficiently answers many of the five Ws and one H.

Frank Sojka was standing in his bedroom when the house shuddered and the ceiling of the living room collapsed in a loud crash.

A small private jet had gone down short of the airport in South Bend, Ind. Sunday afternoon and plowed through three homes, killing two people on the plane and injuring three other people.

The rest of the article contains witness accounts of the disaster.

Later that day, as more information emerged, one of the dead was confirmed to be Steve Davis, a star quarterback at the University of Oklahoma in the 1970s. Shortly after noon that day, in an article written using the inverted pyramid and titled “Ex-Oklahoma QB Killed in Plane Crash in Indiana,” the Associated Press covered the story, including the death of Steve Davis—an intriguing and sad detail:

Steve Davis, Oklahoma’s starting quarterback when it won back-to-back national championships in the 1970s, was one of two people killed when a small aircraft smashed into three homes in northern Indiana, officials said Monday.

In this case, we appreciate another summary lede, with the five Ws and one H answered fairly quickly. The rest of the article examines both Davis and details of the crash, which leaked enough fuel that hundreds were forced to evacuate their homes.

In the above examples, the focus of the story shifted from a small plane crash to the death of a one-time American icon; consequently, the “relevance” of the story changed. Undeterred by this dramatic shift in the story, journalists quickly repackaged it, using the inverted pyramid as an algorithm to quickly disseminate the new angle.

The Internet may make a good home for articles either written in—or inspired by—the inverted pyramid. When using the inverted pyramid, Internet readers can quickly probe a piece.

Some view the inverted pyramid—a structure that’s remained unchanged for almost two hundred years—and the Internet as unlikely bedfellows. “In the professional world, people who are more skeptical of the Web tend to be more traditional and therefore more married to the inverted pyramid,” states Marc Cooper, director of digital news at USC Annenberg. “The concept that underlies the inverted pyramid is not only a great way to tell a story but a great way to think. … It’s going to tell people what’s most important first … grab them with a lede and back it up. … In that sense the concept of the inverted pyramid is not only a valuable way to write news but a valuable way to express yourself.

“The more structural details and the more rigid formulaic details of the inverted pyramid are being eroded by the Web, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that because the important part of the pyramid is the concept. The Web tends to be more conversational than traditional newspaper and more two-way. A lot of the rigidity that’s in the inverted pyramid sort of clashes with the culture of the Web.”

LiveScience, a publisher of scientific news that is sold to news-aggregator websites like Yahoo! and AOL, often writes its news in the inverted-pyramid style. Moreover, news organizations such as Fox and CNN have incorporated blogs into their online offerings, and news in their blog postings is often presented using the inverted pyramid.

Even though the inverted pyramid has endured for centuries and continues to endure in the digital age, as with any other structure, it’s impossible to predict its future. In an e-mail interview, journalism scholar Roy Peter Clark writes, “We all act as if the forms of journalism expression have existed forever. Not true. They are created at particular times in history. Their creation is influenced by the marketplace, by social norms, and by technologies. The inverted pyramid was not created by slaves in ancient Egypt. It is connected to cultural circumstances such as the Civil War, the invention of the telegraph, and the creation of the wire services. Even though we think Shakespeare was one of the greatest writers of English, no one is writing verse plays anymore. So even great forms of writing become exhausted, leaving room for new forms.”

In recent years, academics and journalists have been particularly interested in presenting news in alternative story forms. Alternative story forms present printed news in a fashion other than straight prose. Although alternative story forms come in various iterations, they share some common traits. First, they tell their own story. Second, studies show that alternative story forms tend to grab readers’ attention and are particularly good at helping facts stick in readers’ minds. Third, they are drastically underused in print and online. The EyeTrack studies at Poynter found that in a sample of 16,976 print text elements only 4 percent were alternative story forms.

“Alternative story forms,” says Sara Quinn, the faculty member at the Poynter Institute who directs the EyeTrack research, “are really good at bite-size digestible things. … Maybe [they are] more scientific-type stories [or] fact-laden stories with clear geographic references. Things that you’re going to show side by side [like] putting two candidates up for a mayor’s race. You don’t want to write around numbers.”

Alternative story forms come in, well, many forms:

A full description of every type of alternative story form is outside the scope of this book. I would, however, like to focus on one particularly powerful alternative story form: the Q&A (Question and Answer).

Q&As are reader specific. They frame a story in terms of what readers may ask. They also have multiple points of entry. A reader should be able to understand the article simply by scanning the Q&A and starting at any question. Q&As are probably most closely associated with interviews, but they can also be used with science and medicine.

“The difference between Q&As and more typical narrative profiles is that Q&As require a more dedicated concentration on reading,” says Dr. David E. Sumner, professor of journalism at Ball State University. “The reader wants to read all that information. You’re not doing any work for the reader. You’re just putting the direct quotes out there. It’s not something that generally attracts a casual readership who are just scanning through a magazine. The reader has to be somebody who is interested either in that subject or the person who is being interviewed.”

Sumner also points out that the subject of the Q&A has to meet certain qualifications. “The Q&A has more points of entry. It works with people who you’re interviewing who are more educated and more literate … a person who won’t require a lot of polishing or editing to put their quotes out there.”

Despite their low-maintenance appearance, Q&As can be deceptively difficult to facilitate and write. “There are some people who think it’s lazy writing,” says Joe Leydon, a film critic for Variety. “But Q&As can be quite difficult. You have to make every response self-contained. … If you get somebody who goes off track and wants to tell you a long story … you get nervous.”

With all the budget cuts hitting newsrooms, it’s sad that some skimping and scrounging comes at the expense of graphic artists and web-design teams. Some of the most dynamic and exciting types of news come out of interactive news collaboratives that involve the work of journalists, graphic designers, programmers, and more. As with any interactive media, interactive design engages the reader and elicits an interaction. Interactive design is driven by data that the readers have input or plugged in.

In 2008, The New York Times put out an interactive news piece titled “Pogue-o-matic,” which is hosted David Pogue, a technology columnist for the Times. The “Pogue-o-Matic” snarkily evaluated cameras, camcorders, smartphones, and televisions for the 2009 holiday season, required the user to click the answers to questions, and used video and pop-up screens to display options. (For more on the snarky or playfully irreverent voice, refer to the sidebar in Chapter 16.)

In 2012, The New York Times put out another interesting interactive design piece that focuses on a mixed-race demographic shift currently occurring in America. The piece is titled “Mixed America’s Family Trees,” and audience members are encouraged to submit their own family trees. In one example, the family tree of actor Lou Diamond Phillips can be clicked on, and you can hear him narrate his mixed-race heritage. Of note, Phillips is Filipino, English, Irish, Spanish, and more. (Even though he’s probably most famous for playing Mexican and American Indian roles, by his own admission in the audio clip, he’s about 1/32 or 1/64 Cherokee.)

Much like any good example of online interactive media, usability is of principal importance when designing an interactive design piece. It’s important to avoid overburdening the reader with too many options.

In a Q&A published in the Times, graphics director Steve Duenes writes, “Readers don’t want to spend a lot of time figuring out how something works. Even when there’s a lot of data, the interface should be designed so that the content is easily accessible. Often that means doing some fairly simple things, like limiting the number of menu options or making the descriptive language very clear.”

As with any document, the interactive design piece should serve a purpose and engage the reader. It should take the reader closer to the subject. Finally, because it’s difficult and costly to produce interactive pieces, reusability is important to publications, and templates can serve a useful purpose.

A good example of a simple and reusable interactive design titled “Crime in Chicago” can be found on the Chicago Tribune’s website. By typing in or clicking on a specific area, the reader can access statistics on property crimes, as well as violent and quality-of-life crimes. As you can probably imagine, this example of interactive design can be paired with a variety of stories.

Although not exactly news, you’ll find examples of interactive design in magazines, too. For example, in the January 2013 issue of Wired, there’s an interactive piece titled “Speaking Bad” that enables tablet users to pair quotations with a corresponding antihero. For example, Tyler Durden, the main character in the movie Fight Club, memorably uttered, “It’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.”

Keep in mind that a smart writer is always aware of when interactive design will benefit a story. If your editor is amenable to telling stories using digital tools, feel free to make suggestions.

In 2011, I met for lunch with the editor of The San Diego Union-Tribune (now called U-T San Diego). I was interested in possibly doing some investigative work for the paper—the paper has a remarkable investigative team that won a 2006 Pulitzer Prize for exposing the bribes taken by Congressional Representative Randy “Duke” Cunningham. The editor asked me how comfortable I was with statistics and using statistics programs because a statistician-type job was the only job he could offer me. I told him I had taken a graduate course in statistics and had some familiarity with SPSS Statistics, a statistical software package, but I was no expert. After lunch, we never spoke again. It was at that point that I truly appreciated how different investigative journalism was from the rest of journalism. Proficiency with statistics, however, is only one characteristic that distinguishes the practice of investigative reporting.

Economic concerns are cutting into investigative reporting efforts nationwide. Additionally, some experts contend that the spirit of investigative journalism has been diluted with weekly news shows like 60 Minutes and local news teams pursuing investigations with dubious social merit—such as personal injury and personal financial concerns. Nevertheless, exciting investigative reporting is still being done. For example, in 2010, ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that publishes investigative stories in the public interest, became the first online publication to win a Pulitzer Prize. It then won another Pulitzer in 2011. ProPublica routinely partners with big news organizations when doing investigative work, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and 60 Minutes.

To be sure, investigative reporting has a long and storied history in the United States, dating all the way back to the revolutionary presses and, later, partisan presses. Classically, investigative pieces have been the purview of newspapers, but investigative journalism is also found in books, on websites (ProPublica), and in magazines (Mother Jones). Such reporting played a large role in shaping the United States.

By the turn of the century, early investigative reporters called muckrakers had made their mark and helped bring about social change. In the 1960s, science writer and editor Rachel Carson published her landmark work Silent Spring, which exposed the effects of pesticides on the environment. In the 1970s, a whole generation of journalists were inspired to enter the profession when Washington Post investigative reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein blew the top off the Watergate scandal.

According to The Elements of Journalism, investigative reporting comes in three flavors:

Several characteristics are common to many types of investigative reporting. First, investigative reporters aim to uncover wrongdoing. Second, investigative reporters spend much time sifting through documents and data to make sense of this wrongdoing. Analysis of such data can get complicated and involves the use of statistics and a scientific method to prove hypotheses. Third, investigative reporters often have to deal with a different breed of source, including whistleblowers and “current” and “former” members. Investigative reporters are deeply concerned with the character and motivation of their sources, too. Fourth, sources—especially those at the center of any wrongdoing—are often reluctant to go on record, which poses an entirely different set of obstacles to the investigative reporter. Fifth, investigative reporting practices can be contentious. These practices include the use of anonymous sources, paid sources, ambush interviews, covert reporting, and more.

Although I’ve touched on investigative stories as a type of news article, a full analysis of this type of reporting is outside the scope of this text. For more information on this topic, I suggest reading The Investigative Reporter’s Handbook and visiting the Investigative Reporters & Editors website, specifically perusing the IRE Resource Center.

In 2006, Evan Williams and Biz Stone, formerly of Google, launched Twitter. (Williams had also created Blogger, the popular blogging software.) Twitter was written in the programming language Ruby, and its interface allows open adaptation and integration with other online services. In March 2007, Twitter made its public debut at the South by Southwest music festival and soon became a force to be reckoned with. The number of Twitterers or Twitter users has increased by more than 1300 percent in 2009, and by 2011, users were sending a cyclopean one billion tweets a week!

Twitter is a free SMS (short message service) with a social-networking component. Many texts (known as tweets) are sent by a hegemony of self-obsessed Twitterati (Twitter users who attract thousands or millions of users). A 2009 study published by the Harvard Business Review suggested that the top 10 percent of Tweeters accounted for more than 90 percent of all tweets. Interestingly, this study also shows that unlike other social-media sites, which are often driven by women users, Twitter appeals to nearly as many men as women.

In 2009, the Oxford University Press Dictionary Team found that the second most common word used on Twitter was “I” compared with its place as the tenth most common word in general English text. Other very popular first words also hinted at egocentrism among Tweeters and included watching, trying, listening, reading, and eating. (For those of you who are interested, the word fuck is much more prevalent in Twitterese than in written English—so much for Twitterquette.)

Even though Twitter is often used by celebrities who have a propensity for showing off their tanlines and self-destructive congressmen tweeting pictures of themselves in their skivvies, the medium has shown incredible promise as a vehicle for disseminating news—especially breaking news. On January 15, 2009, citizen journalist Janis Krums broke the news of US Airways flight 1549 landing on the Hudson and uploaded a picture snapped from her camera onto Twitpic.com. Much like the popular press was used to fuel American democracy in the Revolutionary era, Twitter and other social-media sites have been used to herald democratic and political movements both within the United States and across the world. For example, Twitter was integral during 2009 uprisings in Moldova and during Iran’s attempted velvet revolution that same year. Additionally, during his 2012 election campaign, President Barack Obama was a political trailblazer with his savvy use of Twitter and other social-media sites, including Reddit, Spotify, Instagram, Pinterest, and Tumblr. (Sadly, Obama’s popular 2008 Facebook campaign was orphaned somewhere near the beginning of his 2012 campaign preparations.) Obama’s fondness for Twitter in particular dates to the 2008 election, when he famously amassed twenty times as many Twitter followers as Senator John McCain.

“For its users,” write the editors at the Columbia Journalism Review, “Twitter has become a lens to just about any news event you can think of—revolutions, volcanic eruptions, State of the Unions—providing an addictive mix of quips, on the scene reports, and recommended links.”

What’s the best way to use the 140-character count allotted for each tweet? I asked Roy Peter Clark this question, and he suggests using this medium in serial-narrative form—a structure he probably understands better than any other living writer. If the who’s, what’s, where’s, when’s, why’s, how’s, and details could be read in reverse order—so as to make a story out of a Twitter feed—the news being disseminated would make more sense. This advice suggests that narrative transitions may be important when constructing a Twitter feed to report news.

“I enjoy writing on Twitter,” writes Clark, “and I try to write as well as I can in short forms. I never dump stuff. I am always crafting and revising. There is a serious problem with Twitter as a news-delivery system: It works if you are experiencing it in real time. If you come to the party late, you may have missed the most dramatic or newsworthy tweet. I wish I could turn the sequence upside down, which then feels more like a serial narrative.”

When using Twitter to disseminate news, let hyperlinks and multimedia do some of the work of fact. It may be a good idea to link to other websites (using a service such as bitly or TinyURL to shorten the URL), pictures, and videos. You can also use a hash tag to indicate a Trending Topic and thus beef up your tweets.

Andy Carvin, the senior strategist at NPR, does an excellent job of running his Twitter feed. “Carvin,” writes Craig Silverman for the Columbia Journalism Review, “sends hundreds of tweets a day that, taken together, paint a real-time picture of events, opinions, controversies, and rumors related to events in the Middle East.”

Carvin selectively retweets breaking news but also uses crowdsourcing to learn more and verify information. He also engages other Tweeters to provide supporting information such as photos. In order to instill a sense of verification and transparency in his feed, Carvin will often introduce retweets with questions such as, “Anyone else reporting this yet?” or, “How unusual is this?” He’ll also use phrases such as “not confirmed.”

According to the Columbia Journalism Review, Carvin runs into a number of interesting problems when crowdsourcing his Twitter feeds. First, the citizen reporters he often relies on misuse words like “breaking,” “urgent,” and “confirmed,” which are often spelled out in capital letters. Second, the tweets that he reposts often lack needed links to pictures and videos, which he will then request. Third, transparency is an issue, and it’s impossible to figure out whether the source of the original tweet is unbiased. For example, an insurgent in some Arab Springs warzone could be sending out tweets as propaganda.

Transparency seems to be a big problem for all journalists who use Twitter. In the case of some politicians, celebrities, and other well-known people, it’s impossible to tell whether a media-relations team, digital staffer, intern, or assistant is behind the tweet. For example, in November 2012, Michael Oren, then Israeli ambassador to the United States, quickly deleted a tweet posted from his account that said Israel was “willing to sit down with” the terrorist group Hamas “if they [Hamas] just stop shooting at us.” He then blamed the tweet on a staffer.

Not everyone thinks that judging the verification and transparency of tweets is necessary. Marc Cooper, director of the digital news at USC Annenberg, believes that readers have enough common sense to discern the quality of tweets: “I am much more comfortable with ordinary people using their judgment and whatever resource they have to determine what narratives or what sources they’re going to trust rather than have a third party put their stamp of approval on it. … I think it’s a red herring. If certain things are not verifiable or trustworthy, then it implies that there are things that are verifiable and trustworthy. … It has an antidemocratic tinge to it because it implies that there was a time that you could rely on the media to give you this rock-solid information. If you go back to the pre-Web or pre-social media … you will see that the media was highly unreliable and highly biased and highly parochial. There was some great information, and there was a lot of bad information … a lot of unwitting propaganda. … There was a political consensus that permeated the media so you got a certain unrealistic or fragmentary view of the world. In 1955, you could read The Washington Post or New York Times all day and really be wrong.”

Many journalists put much thought into their tweets and draw on their training and experience to craft them. “The skills I would use for a long feature are very similar to the skills I would use in writing a tweet,” says Ted Spiker. “I try to spend some time thinking about the rhythm of a tweet and the placement of the words to get the maximum rhythm and voice to the tweet. Which is exactly the way I would edit a long-form story.”

One potential problem when reporting news through any social-media outlet, including Twitter, is that the media’s existence is dependent on the financial realities and corporate decisions made by the companies who own these sites. Greed for advertising revenue undid websites like MySpace and Digg, and although valuations for sites like Twitter and Facebook are astronomically high, these entities don’t generate huge profits. Nevertheless, Twitter continues to show promise as a disseminator of news.

Many journalists, editors, and academics have recognized that the delivery and consumption of breaking news may best be done by digital means. For the time being, at least, news analysis may be best relegated to print journalism. For example, if a shooting were to occur in a city square somewhere in the world, the story could break on a Twitter or blog feed and be further analyzed the next day in the local newspaper.

“The digital form of communication has overridden everything,” says Cooper. “The bias of digital is to be very fast and to be very common and shared. … Not only blogs but also social media, digital communication, and nontraditional forms of journalism have eclipsed traditional journalism at least in breaking news. When it comes to things that are more refined or analytical, you’ll need more time and room to digest that. … Whether you have news that’s breaking very quickly … whether it’s a fire or whether it’s the overthrow of a government in Egypt … you’re probably going to do better in the initial period by following a Twitter feed than following articles on the CNN blog or AP Wire.”

Current research suggests that readers are equally likely to turn to both traditional (newspaper) and nontraditional (online) mediums for their news. But even as the means by which news is disseminated continues to evolve, actual news reporting will always endure. Before we can analyze and reflect, we must first grapple with the gravity of facts. When the space shuttle Challenger exploded, when terrorists targeted the Twin Towers, and when Hurricane Katrina wiped out the levees in New Orleans, news reports preceded analysis. In times of exigency, we will always retreat to news in its most basic form, whether it’s disseminated by a newspaper, blog, or Twitter feed.