Plan Your Trip

Outdoor Activities

Spain's landscapes are almost continental in their scale and variety, and they provide the backdrop to some of Europe's best hiking, most famously the Camino de Santiago. Skiing is another big draw, as are cycling, water sports, river-rafting and wildlife-watching, among other stirring outdoor pursuits.

Best Hiking

Pyrenees

Parque Nacional de Ordesa y Monte Perdido (June to August): the best of the Pyrenees and Spain's finest hiking.

Cantabria & Asturias

Picos de Europa (June to August): a close second to the Pyrenees for Spain's best hiking.

Andalucía

Las Alpujarras (July and August): snow-white villages in the Sierra Nevada foothills.

Pilgrimage

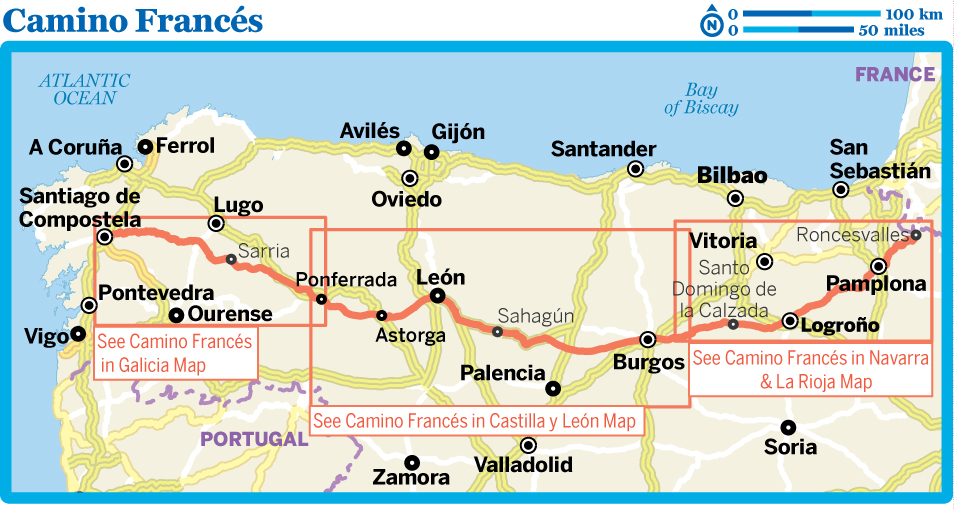

Camino de Santiago (Camino Francés; May to September): one of the world's favourite pilgrimages, across northern Spain from Roncesvalles to Santiago de Compostela.

Coast to Coast

GR11 (Senda Pirenáica; July and August): traverses the Pyrenees from the Atlantic to the Med.

Coastal Walks

Serra de Tramuntana (year-round): Mallorca's jagged western coast with fine villages en route.

Hiking

Spain is famous for superb walking trails that criss-cross mountains and hills in every corner of the country, from the alpine meadows of the Pyrenees to the sultry Cabo de Gata coastal trail in Andalucía. Other possibilities include conquering Spain's highest mainland peak, Mulhacén (3479m), above Granada; following in the footsteps of Carlos V in Extremadura; or walking along Galicia's Costa da Morte (Death Coast). And then there's one of the world's most famous pilgrimage trails – the route to the cathedral in Galicia's Santiago de Compostela.

When to Go

Spain encompasses a number of different climatic zones, ensuring that it's possible to hike year-round. In Andalucía conditions are at their best from March to June and in September and October: they're unbearable from July to August, but from December to February most trails remain open, except in the high mountains.

If you prefer to walk in summer, do what Spaniards have traditionally done and escape to the north. The Basque Country, Asturias, Cantabria and Galicia are best from June to September. The Pyrenees are accessible from mid-June until (usually) September, while July and August are the ideal months for the high Sierra Nevada. August is the busiest month on the trails, so if you plan to head to popular national parks and stay in refugios (pilgrim hostels), book ahead.

Hiking Destinations

Pyrenees

For good reason, the Pyrenees, separating Spain from France, are Spain's premier walking destination. The range is utterly beautiful: prim and chocolate-box pretty on the lower slopes, wild and bleak at higher elevations, and relatively unspoilt compared to some European mountain ranges. The Pyrenees contain two outstanding national parks: Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici and Ordesa y Monte Perdido.

The spectacular GR11 (Senda Pirenáica) traverses the range, connecting the Atlantic (at Hondarribia in the Basque Country) with the Mediterranean (at Cap de Creus in Catalonia). Walking the whole 35- to 50-day route is an unforgettable challenge, but there are also magnificent day hikes in the national parks and elsewhere.

Picos de Europa

Breathtaking and accessible limestone ranges with distinctive craggy peaks (usually hot rock-climbing destinations, too) are the hallmark of Spain's first national park, the Picos de Europa, which straddles the Cantabria, Asturias and León provinces and is fast gaining a reputation as the place to walk in Spain.

Elsewhere in Spain

To walk in mountain villages, the classic spot is Las Alpujarras, near the Parque Nacional Sierra Nevada in Andalucía. The Sierra de Cazorla and Sierra de Grazalema, both also in Andalucía, are also outstanding. The long-distance GR7 trail traverses these three regions – you can walk all or just part of the route, depending on your time and inclination.

Great coastal walking abounds, even in heavily visited areas such as the south coast (try Andalucía's Cabo de Gata). The following are trails that are less known but equally rewarding:

AEls Ports, Valencia

ARuta de Pedra en Sec, Mallorca

ACamí de Cavalls, Menorca

Information

For the full low-down on these walks, including the Camino de Santiago, check out Lonely Planet's Hiking in Spain. Region-specific walking (and climbing) guides are published by Cicerone Press (www.cicerone.co.uk).

Madrid's La Tienda Verde and Librería Desnivel both sell maps (the best Spanish ones are Prames and Adrados) and guides.

Websites

Numerous websites offer local route descriptions but the following three cover a number of Spanish regions, although you'll need to speak Spanish to take full advantage of their descriptions:

Camino de Santiago

'The door is open to all, to sick and healthy, not only to Catholics but also to pagans, Jews, heretics and vagabonds.'

So go the words of a 13th-century poem describing the Camino. Eight hundred years later these words still ring true. The Camino de Santiago (Way of St James) originated as a medieval pilgrimage and, for more than 1000 years, people have taken up the Camino's age-old symbols – the scallop shell and staff – and set off on the adventure of a lifetime to the tomb of St James the Apostle, in Santiago de Compostela, in the Iberian Peninsula's far northwest.

Today the most popular of the several caminos (paths) to Santiago de Compostela is the Camino Francés, which spans 783km of Spain's north from Roncesvalles, on the border with France, to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, and attracts walkers of all backgrounds and ages, from countries across the world. And no wonder: its list of assets (culture, history, nature) is impressive, as are its accolades. Not only is it Council of Europe's first Cultural Itinerary and a Unesco World Heritage site but, for pilgrims, it's a pilgrimage equal to visiting Jerusalem, and by finishing it you're guaranteed a healthy chunk of time off purgatory.

To feel, absorb, smell and taste northern Spain's diversity, for a great physical challenge, for a unique perspective on rural and urban communities, and to meet intriguing travel companions, this is an incomparable walk. 'The door is open to all' …so step on in.

History

In the 9th century a remarkable event occurred in the poor Iberian hinterlands: following a shining star, Pelayo, a religious hermit, unearthed the tomb of the apostle James the Greater (or, in Spanish, Santiago). The news was confirmed by the local bishop, the Asturian king and later the Pope. Its impact is hard to truly imagine today, but it was instant and indelible: first a trickle, then a flood of Christian Europeans began to journey towards the setting sun in search of salvation.

Compostela became the most important destination for Christians after Rome and Jerusalem. Its popularity increased with an 11th-century papal decree granting it Holy Year status: pilgrims could receive a plenary indulgence – a full remission of your lifetime's sins – during a Holy Year. These occur when Santiago's feast day (25 July) falls on a Sunday: the next one isn't until 2021.

The 11th and 12th centuries marked the heyday of the pilgrimage. The Reformation was devastating for Catholic pilgrimages, and by the 19th century, the Camino had nearly died out. In its startling late-20th-century reanimation, which continues today, it's most popular as a personal and spiritual journey of discovery, rather than one primarily motivated by religion.

PILGRIM HOSTELS

There are around 300 refugios (pilgrim hostels) along the Camino, owned by parishes, 'friends of the Camino' associations, private individuals, town halls and regional governments. While in the early days these places were run on donations and provided little more than hot water and a bed, today's pilgrims are charged €5 to €10 and expect showers, kitchens and washing machines. Some things haven't changed though – the refugios still operate on a first-come, first-served basis and are intended for those doing the Camino solely under their own steam.

Routes

Although in Spain there are many caminos (paths) to Santiago, by far the most popular is, and was, the Camino Francés, which originated in France, crossed the Pyrenees at Roncesvalles and then headed west for 783km across the regions of Navarra, La Rioja, Castilla y León and Galicia. Waymarked with cheerful yellow arrows and scallop shells, the 'trail' is a mishmash of rural lanes, paved secondary roads and footpaths all strung together. Starting at Roncesvalles, the Camino takes roughly two weeks cycling or five weeks walking.

But this is by no means the only route, and the summer crowds along the Camino Francés have prompted some to look at alternative routes – in 2005, nearly 85% of walkers took the Camino Francés; by 2013 this had fallen to 70%. Increasingly popular routes include the following:

ACamino Portugués North to Santiago through Portugal.

ACamino del Norte Via the Basque Country, Cantabria and Asturias.

AVia de la Plata From Andalucía north through Extremadura, Castilla y León and on to Galicia.

A very popular alternative is to walk only the last 100km (the minimum distance allowed) from Sarria in Galicia in order to earn a Compostela certificate of completion given out by the Catedral de Santiago de Compostela.

Another possibility is to continue on beyond Santiago to the dramatic, 'Lands End' outpost of Fisterra (Finisterre), an extra 88km.

Information

For more information about the Credencial (like a passport for the Camino, in which pilgrims accumulate stamps at various points along the route) and the Compostela certificate, visit the website of the cathedral's Oficina del Peregrino (Pilgrim's Office; www.peregrinossantiago.es; Rúa do Vilar 3, Santiago de Compostela).

There are a number of excellent Camino websites:

ACaminolinks (www.caminolinks.co.uk) Complete, annotated guide to many Camino websites.

AMundicamino (www.mundicamino.com) Excellent, thorough descriptions and maps.

ACamino de Santiago (www.caminodesantiago.me) Contains a huge selection of news groups, where you can get all of your questions answered.

When to Walk

People walk and cycle the Camino year-round. In May and June the wildflowers are glorious and the endless fields of cereals turn from green to toasty gold, making the landscapes a huge draw. July and August bring crowds of summer holidaymakers and scorching heat, especially through Castilla y León. September is less crowded and the weather is generally pleasant. From November to May there are fewer people on the road as the season can bring snow, rain and bitter winds. Santiago's feast day, 25 July, is a popular time to converge on the city.

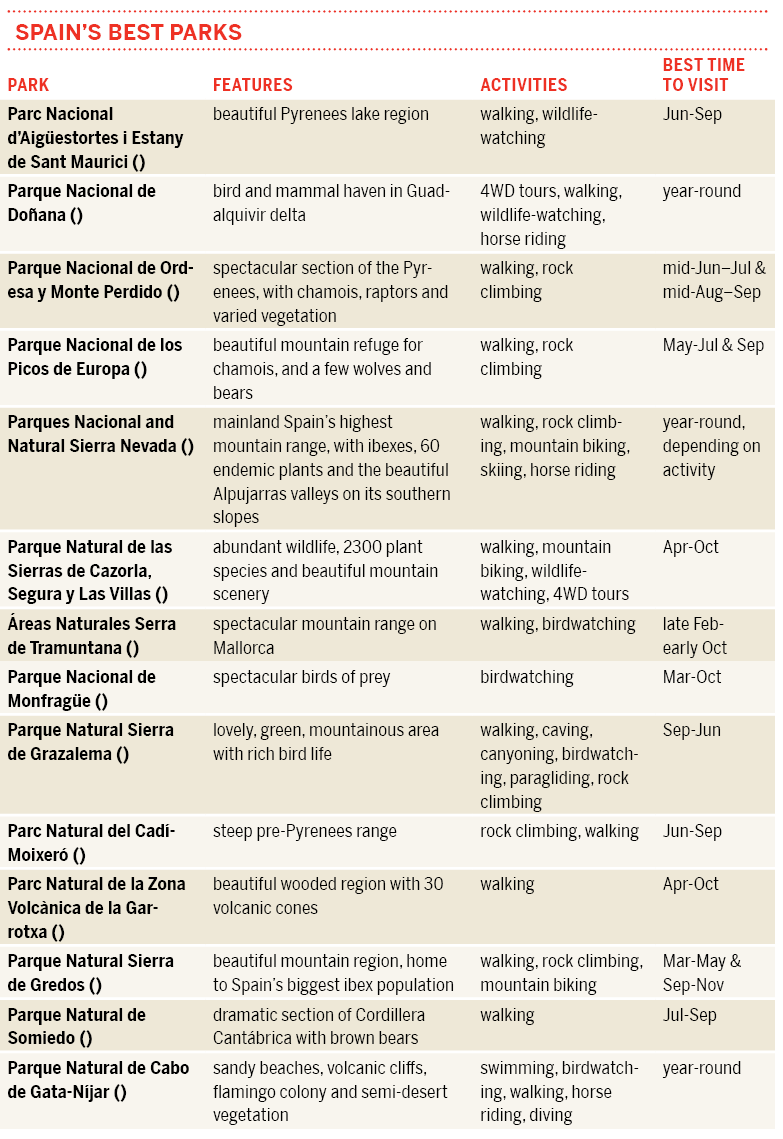

National & Natural Parks

Much of Spain's most spectacular and ecologically important terrain – about 40,000 sq km or 8% of the entire country, if you include national hunting reserves – is under some kind of official protection. Nearly all of these areas are at least partly open to walkers, naturalists and other outdoor enthusiasts, but degrees of conservation and access vary.

The parques nacionales (national parks) are areas of exceptional importance and are the country's most strictly controlled protected areas. Spain has 14 national parks – nine on the mainland, four on the Canary Islands and one in the Balearic Islands. The hundreds of other protected areas fall into at least 16 classifications and range in size from 100-sq-metre rocks off the Balearics to Andalucía's 2140-sq-km Parque Natural de Cazorla.

Canyoning

For exhilarating descents into steep-walled canyons by any means possible (but in the care of professional guides), look no further than Alquézar in Aragón, one of Europe’s prime locations for this popular sport. Alquézar’s numerous activities operators can also arrange rock climbing and rafting in the surrounding Sierra de Guara.

Canyoning is also possible in the following places:

ACangas de Onís in Picos de Europa

ATorrent de Pareis and Gorg Blau in Mallorca

ROCK CLIMBING

Spain offers plenty of opportunities to see the mountains and gorges from a more vertical perspective. For an overview of Spanish rock climbing, check out the Spain information on the websites of Rockfax (www.rockfax.com) and Climb Europe (www.climb-europe.com). Both include details on the best climbs in the country. Rockfax also publishes various climbing guidebooks covering Spain.

Cycling

Spain has a splendid variety of cycling possibilities, from gentle family rides to challenging two-week expeditions. If you avoid the cities (where cycling can be somewhat nerve-racking), Spain is also a cycle-friendly country, with drivers accustomed to sharing the roads with platoons of Lycra-clad cyclists. The excellent network of secondary roads, usually with comfortable shoulders to ride on, is ideal for road touring.

Cycling Destinations

Every Spanish region has both off-road (called BTT in Spanish, from bici todo terreno, meaning 'mountain bike') and touring trails and routes. Mountain bikers can head to just about any sierra (mountain range) and use the extensive pistas forestales (forestry tracks).

One highly recommended and challenging off-road excursion takes you across the snowy Sierra Nevada. Classic long-haul touring routes include the Camino de Santiago, the Ruta de la Plata and the 600km Camino del Cid, which follows in the footsteps of Spain's epic hero, El Cid, from Burgos to Valencia. Guides in Spanish exist for all of these, available at bookshops and online.

Mallorca is another popular cycling destination, for everyone from ordinary travellers to Bradley Wiggins, 2012 Tour de France winner, who trains on the mountain roads of the Serra de Tramuntana.

VIAS VERDES

Spain has a growing network of Vias Verdes (literally 'green ways', but equivalent to the 'rail trail' system in other countries), an outstanding system of decommissioned railway tracks that have been converted into bicycle (or hiking) trails. There are more than 2000km of these trails spread across (at last count) 102 routes all across the country, and they range from 1.2km to 84.4km in length. Check out www.viasverdes.com for more information.

Information

An indispensable Spanish-language cycling website is www.amigosdelciclismo.com, which gives useful information on restrictions, updates on laws, circulation norms, contact information for cycling clubs and lists of guidebooks, as well as a lifetime's worth of route descriptions organised region by region.

Bike Spain in Madrid is one of the better cycling tour operators.

Many of the cycling guidebooks in publication are in Spanish:

AEspaña en bici, by Paco Tortosa and María del Mar Fornés. A good overview guide, but quite hard to find.

ACycle Touring in Spain: Eight Detailed Routes, by Harry Dowdell. A helpful planning tool; also practical once you're in Spain.

AThe Trailrider Guide – Spain: Single Track Mountain Biking in Spain, by Nathan James and Linsey Stroud. Another good resource.

HANG-GLIDING & PARAGLIDING

It's not what most people do on their summer holidays, but if you want to take to the skies either ala delta (hang-gliding) or parapente (paragliding), there are a number of specialised clubs and adventure-tour companies here. The Real Federación Aeronáutica España (www.rfae.org) gives information on recognised schools and lists clubs and events.

Skiing & Snowboarding

For winter powder, Spain's skiers (including the royal family) head to the Pyrenees of Aragón and Catalonia. Outside the peak periods (the beginning of December, 20 December to 6 January, Carnaval and Semana Santa), Spain's top resorts are relatively quiet, cheap and warm in comparison with their counterparts in the Alps.

The season runs from December to April, though January and February are generally the best, most reliable times for snow. However, in recent years snow fall has been a bit unpredictable.

Skiing & Snowboarding Destinations

In Aragón, two popular resorts are Formigal and Candanchú. Just above the town of Jaca, Candanchú has some 42km of runs with 51 pistes (as well as 35km of cross-country track). In Catalonia, Spain's first resort, La Molina, is still going strong and is ideal for families and beginners. Considered by many to have the Pyrenees' best snow, the 72-piste resort of Baqueira-Beret boasts 30 modern lifts and 104km of downhill runs for all levels.

Spain's other major resort is Europe's southernmost: the Sierra Nevada, outside Granada. The 80km of runs here are at their prime in March, and the slopes are particularly suited for families and novice-to-intermediate skiers.

Information

If you don't want to bring your own gear, Spanish ski resorts have equipment hire, as well as ski schools. Lift tickets cost between €35 and €50 per day for adults, and €25 and €35 for children; equipment hire costs from around €20 per day. If you're planning ahead, Spanish travel agencies frequently advertise affordable single- or multi-day packages with lodging included.

An excellent source of information on snowboarding and skiing in Spain (and the rest of Europe) is www.skisnowboardeurope.com.

Scuba-Diving & Snorkelling

There's more to Spain than what you see on the surface – literally! Delve under the ocean waves anywhere along the country's almost 5000km of shoreline and a whole new Spain opens up, crowded with marine life and including features such as wrecks, sheer walls and long cavern swim-throughs.

The numerous Mediterranean dive centres cater to an English-speaking market and offer single- and multi-day trips, equipment rental and certification courses. Their Atlantic counterparts (in San Sebastián, Santander and A Coruña) deal mostly in Spanish, but if that's not an obstacle for you, the colder waters of the Atlantic will offer a completely different, and very rewarding, underwater experience.

A good starting point is the reefs along the Costa Brava, especially around the Illes Medes marine reserve, off L'Estartit (near Girona). On the Costa del Sol, operators launch to such places as La Herradura Wall, the Motril wreck and the Cavern of Cerro Gordo. Spain's Balearic Islands are also popular dive destinations with excellent services – Port d'Andratx (Mallorca), for example, has a number of dive schools.

Paco Nadal's book Buceo en España provides information province by province, with descriptions of ocean floors, dive centres and equipment rental.

Surfing

The opportunity to get into the waves is a major attraction for beginners and experts alike along many of Spain's coastal regions. The north coast of Spain has, debatably, the best surf in mainland Europe.

The main surfing region is the north coast, where numerous high-class spots can be found, but Atlantic Andalucía gets decent winter swells. Despite the flow of vans loaded down with surfboards along the north coast in the summer, it's actually autumn through to spring that's the prime time for a decent swell, with October probably the best month overall. The variety of waves along the north coast is impressive: there are numerous open, swell-exposed beach breaks for the summer months, and some seriously heavy reefs and points that only really come to life during the colder, stormier months.

Surfing Destinations

The most famous wave in Spain is the legendary river-mouth left at Mundaka. On a good day, there's no doubt that it's one of the best waves in the world. However, it's not very consistent, and when it's on, it's always very busy and ugly.

Heading east, good waves can be found throughout the Basque Country. Going west, into neighbouring regions of Cantabria and Asturias, you'll also find a superb range of well-charted surf beaches, such as Rodiles in Asturias and Liencres in Cantabria. If you're looking for solitude, some isolated beaches along Galicia's beautiful Costa da Morte remain empty even in summer. In southwest Andalucía there are a number of powerful, winter beach breaks, and weekdays off Conil de la Frontera (located just northwest of Cabo de Trafalgar) can be sublimely lonely.

Information

In summer a shortie wetsuit (or, in the Basque Country, just board shorts) is sufficient along all coasts except Galicia, which picks up the icy Canaries current – you'll need a light full suit here.

Surf shops abound in the popular surfing areas and usually offer board and wetsuit hire. If you're a beginner joining a surf school, ask the instructor to explain the rules and to keep you away from the more experienced surfers.

There are a number of excellent surf guidebooks to Spain:

ALonely Planet author Stuart Butler's English-language Big Blue Surf Guide: Spain.

AJosé Pellón's Spanish-language Guía del Surf en España.

ALow Pressure's superb Stormrider Guide: Europe – the Continent.

Windsurfing & Kitesurfing

The best sailing conditions are to be found around Tarifa, which has such strong and consistent winds that it's said that the town's once-high suicide rate was due to the wind turning people mad. Whether or not this is true, one thing is without doubt: Tarifa's 10km of white, sandy beaches and perfect year-round conditions have made this small town the windsurfing capital of Europe. The town is crammed with windsurf and kite shops, windsurfing schools and a huge contingent of passing surfers. However, the same wind that attracts so many devotees also makes it a less than ideal place to learn the art.

If you can't make it as far south as Tarifa, then the less-known Empuriabrava in Catalonia also has great conditions, especially from March to July, while the family resort of Oliva near Valencia, Murcia's Mar Menor, or Fornells on Menorca are also worth considering. If you're looking for waves, try Spain's northwest coast, where Galicia can have fantastic conditions.

Information

An excellent guidebook to windsurfing and kitesurfing spots across Spain and the rest of Europe is Stoked Publications' The Kite and Windsurfing Guide: Europe.

The Spanish-language website www.windsurfesp.com gives very thorough descriptions of spots, conditions and schools all over Spain.

Kayaking, Canoeing & Rafting

Opportunities abound in Spain for taking off downstream in search of white-water fun along its 1800 rivers and streams. As most rivers are dammed for electric power at some point along their flow, there are many reservoirs with excellent low-level kayaking and canoeing, where you can also hire equipment.

In general, May and June are best for kayaking, rafting, canoeing and hydrospeeding (water tobogganing). Top white-water rivers include Catalonia's turbulent Noguera Pallaresa, Aragón's Gállego and Ésera, Cantabria's Carasa and Galicia's Miño.

For fun and competition, the crazy 22km, en-masse Descenso Internacional del Sella canoe race is a blast, running from Arriondas in Asturias to coastal Ribadesella. It's held on the first weekend in August.

Patrick Santal's White Water Pyrenees thoroughly covers 85 rivers in France and Spain for kayakers, canoeists and rafters.

Wildlife Tourism

Spain is home to some of Europe's most interesting wildlife, from abundant bird species (both resident and migratory) to the charismatic carnivores that have made a comeback.

Information

The following online and book resources will help guide your steps and provide fascinating background information when watching wildlife in Spain.

AFundación Oso Pardo Spain's main resource for brown bears.

ALife Lince (www.lifelince.org) Up-to-the-minute news on the Iberian lynx.

AIberia Nature (www.iberianature.com) An excellent English-language source of information on Spanish fauna and flora, although some sections need an update.

AWild Spain, by Teresa Farino (2009). Useful practical guide to Spain's wilderness and wildlife areas.

ACollins Bird Guide: The Most Complete Guide to the Birds of Britain & Europe, by Lars Svensson et al (2009).

Tour Operators

AIberian Wildlife (www.iberianwildlife.com) A full portfolio of wildlife tours.

ANature Trek (www.naturetrek.co.uk) Birds, wolves and bears, as well as lynx-watching trips into the Parque Natural Sierra de Andújar and Doñana.

AJulian Sykes Wildlife Holidays (www.juliansykeswildlife.com) Birdwatching, Iberian lynx in Parque Natural Sierra de Andújar and other small-group trips.

AWildwatching Spain (www.wildwatchingspain.com) Wolves and Iberian lynx are the standouts among many tours.

Animals

There are around 85 terrestrial mammal species in Spain, 70 reptiles and amphibians and some 227 different species of butterflies.

In addition to the three predator species covered at length below, other wildlife highlights to watch out for include the following:

ACabra montés (ibex) Chiefly found in Castilla y León's Sierra de Gredos and in the mountains of Andalucía.

ABarbary macaques Gibraltar's 'apes' are Europe's only wild monkeys.

AMarine mammals Dolphin- and whale-spotting boat trips are a popular attraction in Gibraltar and nearby Tarifa.

Brown Bears

One of the most impressive of Spain's flagship species is the oso pardo (brown bear), of which an estimated 240 remain in the wild. The overwhelming majority of Spain's bears inhabit the Cordillera Cantábrica. There is also a tiny population in the Pyrenees (in France and Andorra as well as Spain, with less than 30 bears in total), although the last known native Pyrenean bear died in October 2010. The current population is entirely made up of introduced bears from Slovenia and their offspring.

Hunting or killing Spain's bears has been banned since 1973, and expensive conservation programs have started to pay off in the last few years, at least in the western Cordillera Cantábrica, where the population is considered viable for future survival – their numbers have almost doubled in the past decade.

The best place to see brown bears in the wild is undoubtedly the Parque Natural de Somiedo in southwestern Asturias. There is also a small chance of seeing bears in the Picos de Europa. A bear enclosure and breeding facility at Senda del Oso, also in Asturias, is a good chance to get a little closer.

Iberian Wolf

The lobo ibérico (Iberian wolf) is, like the brown bear, on the increase. Though heavily protected, wolves are still considered an enemy by many country people, although from a population low of around 500 in 1970, Spain now has between 2000 and 2500. The species is found in small populations across the north, including the Picos de Europa, but their heartland is the mountains of Galicia and northwestern Castilla y León. The most accessible population is in the Sierra de Culebra, close to Zamora, and where Zamora Natural runs wolf-watching expeditions. Riaño, close to León, is another possibility.

Iberian Lynx

The beautiful Iberian lynx, Europe’s only big-cat species, is the most endangered feline species in the world. It once inhabited large areas of the peninsula, but numbers fell to as few as 120 at the beginning of the 21st century. A highly successful captive breeding program and the reintroduction of captive-bred lynx into the wild, along with restocking of rabbit populations (rabbits make up more than 80% of the lynx's diet), have seen the wild population reach an estimated 320 individuals, with a further 150 in captivity.

The two remaining lynx populations are in Andalucía: the Parque Nacional de Doñana (with 85 lynxes); and the Sierra Morena (235 lynx) spread across the Guadalmellato (northeast of Córdoba), Guarrizas (northeast of Linares) and Andújar-Cardeña (north of Andújar) regions. There are also plans for new wild populations to be established in Portugal, north of Seville and in the Montes de Toledo in Castilla-La Mancha.

A number of private operators offer 4WD or horseback excursions into the Parque Nacional de Doñana and/or the adjacent natural park from the village of El Rocio or from Sanlúcar de Barrameda. Companies include Doñana Nature, Doñana Ecuestre, Cooperativa Marismas del Rocio, Donana Reservas, and Visitas Donana. These represent the best opportunities to see the lynx in the wild.

Otherwise, the Parque Natural Sierra de Andújar or the Parque Natural Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro are your best bet to see these elusive creatures. While you can explore either of these parks under your own steam, Lynxaia (![]() %625 512442; www.lynxaia.com) covers the Parque Natural Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro.

%625 512442; www.lynxaia.com) covers the Parque Natural Sierra de Cardeña y Montoro.

Birds

With around 500 species Spain has easily the biggest and most varied bird population in Europe. Around 25 species of birds of prey, including the águila real (golden eagle), buitre leonado (griffon vulture) and alimoche (Egyptian vulture), breed here. Although the white stork is everywhere (its large and ungainly nests rest atop electricity pylons, trees and towers), much rarer is the cigüeña negra (black stork), which is down to about 200 pairs in Spain.

Spain's extensive wetlands make it a haven for water birds. The most important of the wetlands is the Parque Nacional de Doñana and surrounding areas in the Guadalquivir delta in Andalucía. Hundreds of thousands of birds winter here, and many more call in during the spring and autumn migrations. Doñana is also home to a population of the highly endangered águila imperial (imperial eagle).

Other outstanding birdwatching sites around the country include the following:

AParque Nacional de Monfragüe, Extremadura The single most spectacular place to observe birds of prey.

ALaguna de Gallocanta, Aragón Thousands of patos (ducks) and grullas (cranes) winter here at Spain's biggest natural lake.

ALa Albufera, Valencia Important coastal wetland for migratory species.

AEbro Delta, Catalonia Another important wetland area.

ALaguna de Fuente de Piedra, Andalucía One of Europe's two main breeding sites for the flamenco (greater flamingo), with as many as 20,000 pairs rearing chicks in spring and summer.

APyrenees Good for birds of prey.